Thomas Lincoln Reconsidered

Thomas Lincoln has been the subject of description and judgment since at least 1860 when a political biography of his son Abraham was written. Since then, thousands of books have been written about Abraham with most having brief descriptions of Thomas. Those written shortly after Abraham’s death were assembled quickly to meet the demand for a record of Abraham’s life and accomplishments. Some elevated Abraham to Biblical heights. Indeed, he became Father Abraham. As Abraham rose to the heavens, Thomas was pushed into a hellish abyss. From that postmortem period to present, most published critical judgments of Thomas conclude that he was a miserable failure both as a man and as a father. That is today’s conventional wisdom among Lincoln historians. It is time to take a fresh look at Thomas and reconsider those judgments and that wisdom.

There have been a few historians who differed with the conventional wisdom. In 1942, Louis A. Warren wrote a critique clearly describing what he thought was the unfair demonization of Thomas Lincoln.

Thomas Lincoln has been the scapegoat for all who would make Lincoln a saint… As one writer put it: “Not a single one of Mr. Lincoln’s deifiers has had the audacity to claim anything superior for Tom Lincoln.” Folklore and tradition have made him one of the most despised characters in American history, and as long as he is portrayed as a vagabond, an idler, a tramp, a rover, and as poor white trash, lacking in energy, void of ambition, wanting in respectability, and a general failure in life, it will be impossible to trace any tendencies which the President may have inherited from his father.

Warren was not alone in his sympathetic view of Thomas. Some teachers, historians, writers, historical societies, and Lincoln aficionados who lived in Indiana and Kentucky agreed with Warren’s assessment of Thomas. Scholars distant from the Indiana-Kentucky scene ignored and brushed aside the locals as provincial defenders of their own and Thomas’s home turf. The conventional wisdom that Thomas was a deplorable man and father survived and remains alive and well today.

Until a few years ago, I accepted the conventional wisdom and was among those who judged Thomas a worthless failure. After all, these were the judgments made by several of my closest friends and preeminent Lincoln biographers. I was unaware of the small band of Indiana and Kentucky dissenters, the Warren school, and I had no basis for accepting their judgments and rejecting those of my friends and Lincoln biographers.

Then I discovered a whole new Thomas Lincoln. He was revealed to me by Indiana and Kentucky friends of the Warren school who are part of a growing, somewhat silent, unorganized, subculture of Thomas Lincoln revisionists. Their voices are quiet and unpretentious, but what they say resounded in my ears like a loud clap of summer thunder rolling across the Illinois prairie.

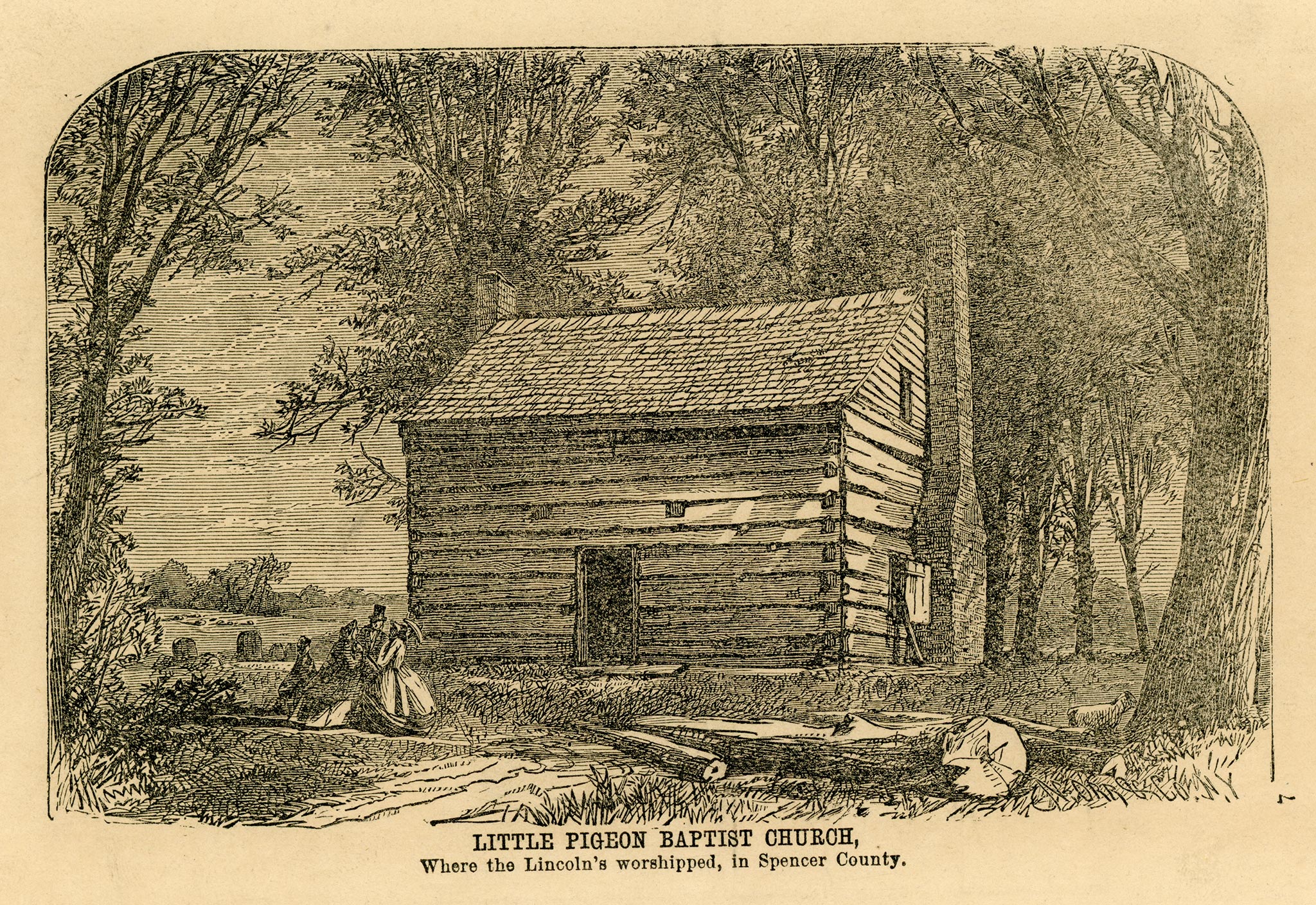

The revisionists strongly disagree with the conventional descriptions of Thomas Lincoln found in many contemporary biographies. To support their position, they point to Thomas’s role in religious and civil affairs of the communities where he lived. He was quite active in his Baptist church, where he served as a well-respected counselor and contributor to the building of a new church meeting place. Before every meal he asked a simple blessing. Fit and prepare us for humble service. We beg for Christ’s sake, Amen.

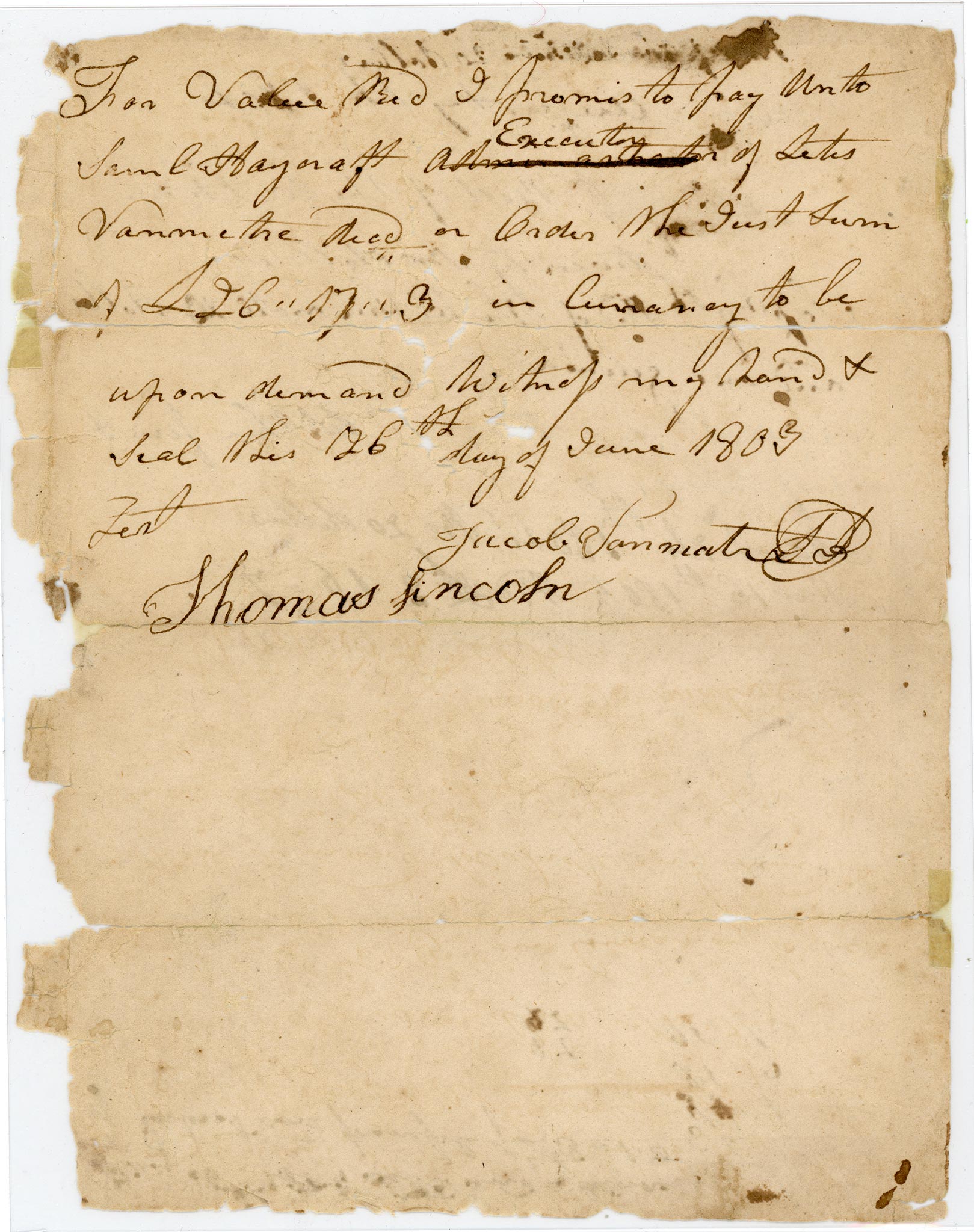

He also served in many civil positions in Hardin County, Kentucky. He was a juror on many occasions, a jail guard, a member of the militia, a road commissioner and a tax payer. He paid for the limited education of his children and stepchildren on every available occasion. He was not materialistic and was generous almost to a fault in assisting those in need. By the standards of the burghers of any small community, Thomas was a respected member of his community.

Thomas left no letters or diaries, but he did leave a body of work as significant as any writer or artist. His work is in the cabinets and cupboards that he created and left for us to see and enjoy. The revisionists generously shared photographs of these pieces and information about Thomas’s abilities as a cabinet maker. And not just a rough cabinet maker, but a master, whose pieces are treasured by private collectors, museums, and universities. The State of Illinois owns two magnificent pieces that unfortunately are in storage rather than on display.

As I learned more about Thomas’s beautiful cabinets, I came to agree with the revisionists. Thomas was truly a master craftsman with superior artistic and mathematical skills. This became even more remarkable when I learned that Thomas was blind in one eye at least since he first moved to Indiana and that his eyesight continued to decline. By the time of his death, he was most likely blind in the other eye. In modern parlance, he was physically disabled and would have been eligible for public assistance. All of this important information was new to me as well it might now be to those biographers who have judged Thomas harshly.

As I examined other aspects of Thomas’s life and character, I continued to discover a man unlike the one I knew from Lincoln biographers. He and his famous son were very different in their views of the world and their hoped-for positions in the future of that world. Thomas’s view was simple. It was a matter of fact, unconscious acceptance of a hard and unjust life consumed by a-day-to-day survival on the edge of the American frontier and spiritually dependent on a literal and judgmental Lord. To the contrary, Abraham’s world-view was cerebral. He consciously and expansively examined life and its possibilities beyond the day-to-day grueling fight for survival. Abraham’s world-view was a luxury made possible by the preceding survival mentality of Thomas and the early pioneers. Their struggles made possible the fresh world-view of the next generation.

Despite their fundamental differences in world-views, they remained respectful and loving of one another. Their differences did not create hatred or disgust. In fact, their “differences” were nothing more than the age-old father-son rivalry and tension common to man since the beginning of time.

In analyzing and describing the relationship between father and son, some historians have interpreted letters and events to show Abraham’s disrespect for his father. These interpretations need to be reexamined.

One such interpretation is of letter that Abraham wrote to his stepbrother, John D. Johnston, regarding Thomas Lincoln as he lay sick and dying. The letter is dated January 12, 1851, five days before Thomas died, and 22 days after Willie Lincoln’s birth, and was in response to a letter from John requesting that Abraham come visit his father. Abraham’s response letter said he could not come because Mary had just had a baby and was sick-abed. Some historians have offered certain parts of Abraham’s letter as evidence of his disdain for his father. Here is Abraham’s letter.

Dear Brother [John D. Johnston]:

Springfield, Jany. 12. 1851–

On the day before yesterday I received a letter from Harriett, written at Greenup. She says she has just returned from your house; and that Father [is very] low, and will hardly recover. She also s[ays] you have written me two letters; and that [although] you do not expect me to come now, yo[u wonder] that I do not write. I received both your [letters, and] although I have not answered them, it is no[t because] I have forgotten them, or been uninterested about them—but because it appeared to me I could write nothing which could do any good. You already know I desire that neither Father or Mother shall be in want of any comfort either in health or sickness while they live; and I feel sure you have not failed to use my name, if necessary, to procure a doctor, or any thing else for Father in his present sickness. My business is such that I could hardly leave home now, if it were not, as it is, that my own wife is sick-abed. (It is a case of baby-sickness, and I suppose is not dangerous.) I sincerely hope Father may yet recover his health; but at all events tell him to remember to call upon, and confide in, our great, and good, and merciful Maker; who will not turn away from him in any extremity. He notes the fall of a sparrow, and numbers the hairs of our heads; and He will not forget the dying man, who puts his trust in Him. Say to him that if we could meet now, it is doubtful whether it would not be more painful than pleasant; but that if it be his lot to go now, he will soon have a joyous [meeting] with many loved ones gone before; and where [the rest] of us, through the help of God, hope ere-long [to join] them.

Write me again when you receive this.

Affectionately,

A. LINCOLN

Abraham’s letter is beautifully poignant in its gentle words to be given to his father in his final illness. It is the Lincoln of our better angels. However, some have interpreted the letter as acceptable evidence of the low regard with which Abraham considered his father.

That interpretation, I believe, lies largely in Abraham’s use of the word “painful” as a description of the sorrow he would feel if he were to see his father on his deathbed. But the pain that he would experience and that he intended to convey was not a loathing or disdainful pain, but rather a sorrowful pain. The loathing pain interpretation would be totally contrary to Abraham’s nature, a nature that found it hard to harm an ant, turtle, turkey, or small animal, much less his father on his deathbed.

If the “loathing pain” interpretation were true, it would be Abraham and not Thomas who would and should suffer in repute. What son would write such a cruel letter to his 73-year-old father in his final moments of life? A dastardly, mean-spirited, and cruel son. Abraham had none of those characteristics.

When the letter was received, Thomas was on his deathbed. He was partially if not totally blind and very weak. He was probably beyond the point of being capable of reading Abraham’s letter, let alone being able to understand what it said. His wife Sarah, however, was not. It would have been Sarah, not Thomas, who would have been the recipient of Abraham’s cruel judgment of Thomas. Surely, Abraham would have realized this as he wrote the letter, and he would not have hurt his beloved stepmother in this way.

To support the “loathing pain” interpretation, some point out that Abraham did not attend his father’s funeral that was held only a short time after the January letter. Some suggest and some with great certitude assert that Abraham’s absence is clear evidence of his disdain for his father.

But, one must ask, who would suffer the shame of Abraham’s slight? Not Thomas. He was dead. It would have been Sarah, and Abraham would not have punished poor Sarah in this manner. Acts of intentional, harmful judgment were not something that were a part of Lincoln’s character. It would be presumptuous to think that Abraham left us little clues of his hatred of his father, clues that future historians might examine like tea leaves and discern the truth of that relationship.

Common sense is often the best method to determine the meaning of human activity or inactivity. In 1851, communication and travel were slow. Burials were not. By the time Abraham learned of his father’s death, arranged for the care of his Springfield family, and undertook a 100-mile journey across the January Illinois prairie to Coles County, the funeral would have been long over.

And if one accepts the premise that important deductions can be made about one’s feelings for another by failure to attend a funeral, then why no similar analysis and judgment about Mary and her father, Robert Todd? Neither Mary nor Abraham Lincoln attended his funeral after his death at age 58, on July 17, 1849, in Lexington, Kentucky.

One cannot conclude that Abraham did not attend his father’s funeral because he disliked him or had extreme, unresolved issues with him. I believe that it was the living, Mary and the new baby boy Willie, and their needs that Abraham chose to care for rather than his father’s final illness and death. To read more into Abraham’s failure to attend his father’s funeral defies common sense and is a real stretch.

I conclude that Thomas Lincoln was a man well suited for his place and time — on the edge of the 19th Century American western frontier with thousands of other like men. He moved into places where there was little or no semblance of western civilization and brought the rough, foundational elements of that civilization to those new places. He did so by establishing a home, raising a family, providing for them through subsistence farming and masterful cabinet making, participating in the churches, the militia, and public institutions of the communities where he lived and fending off the last resistances of the American Indians. He rightfully and thankfully demanded that his son assist in these tasks as he grew. Without the vanguard of Thomas and his ilk, the subsequent flow of American settlers could not have occurred. There would have been no Abraham Lincoln.

I respectfully urge Lincoln historians to take a fresh look at Thomas Lincoln and reconsider their judgments. To do so will not only be a pursuit of truth, but will also answer the call of the better angels within us.

Richard E. Hart is Past President and current Board member of the Abraham Lincoln Association. This article previously appeared in the Association’s For the People.