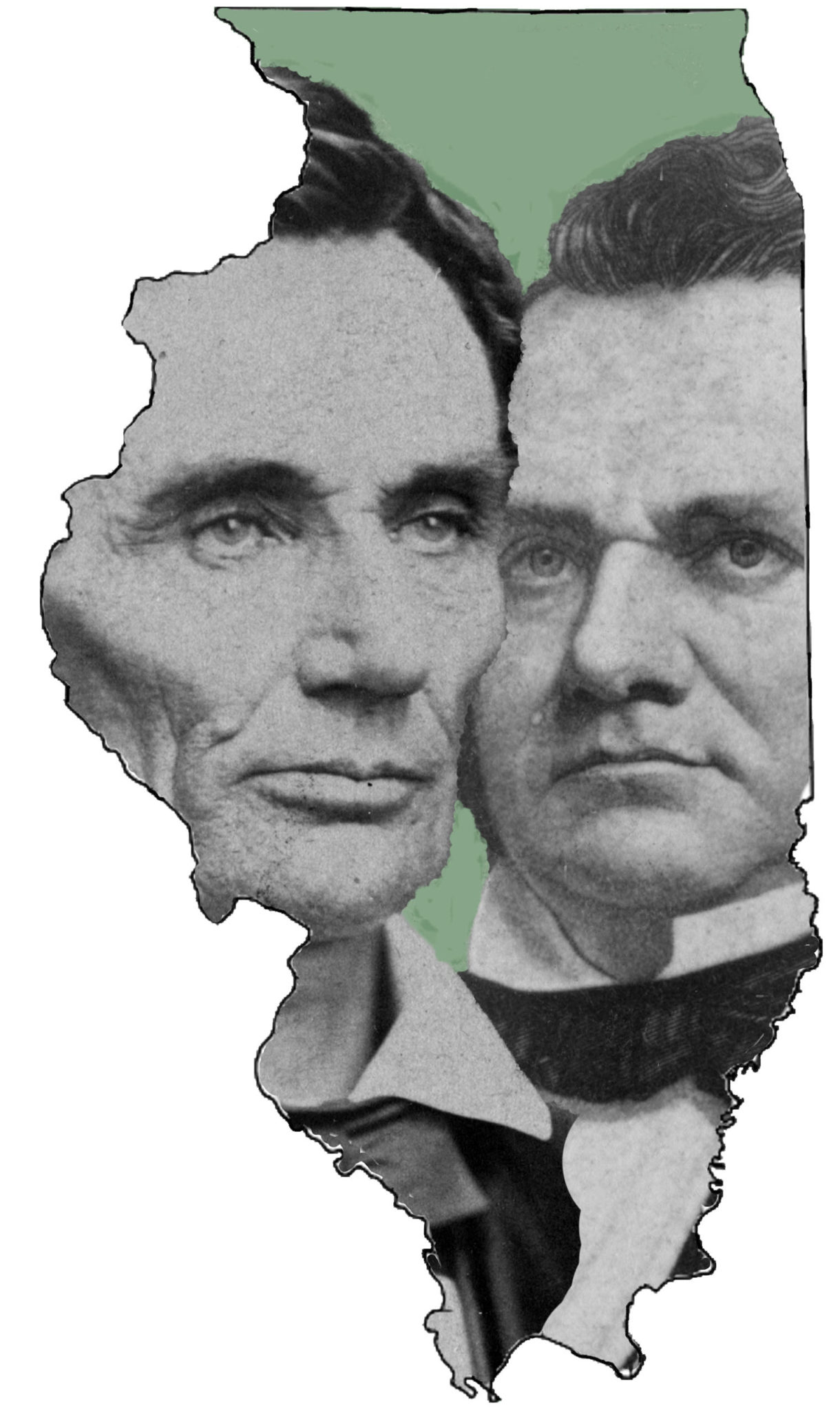

Interview with Harold Holzer on the 160th Anniversary of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Sara Gabbard: In 1858, was there already a precedent for debates between competing candidates for political office?

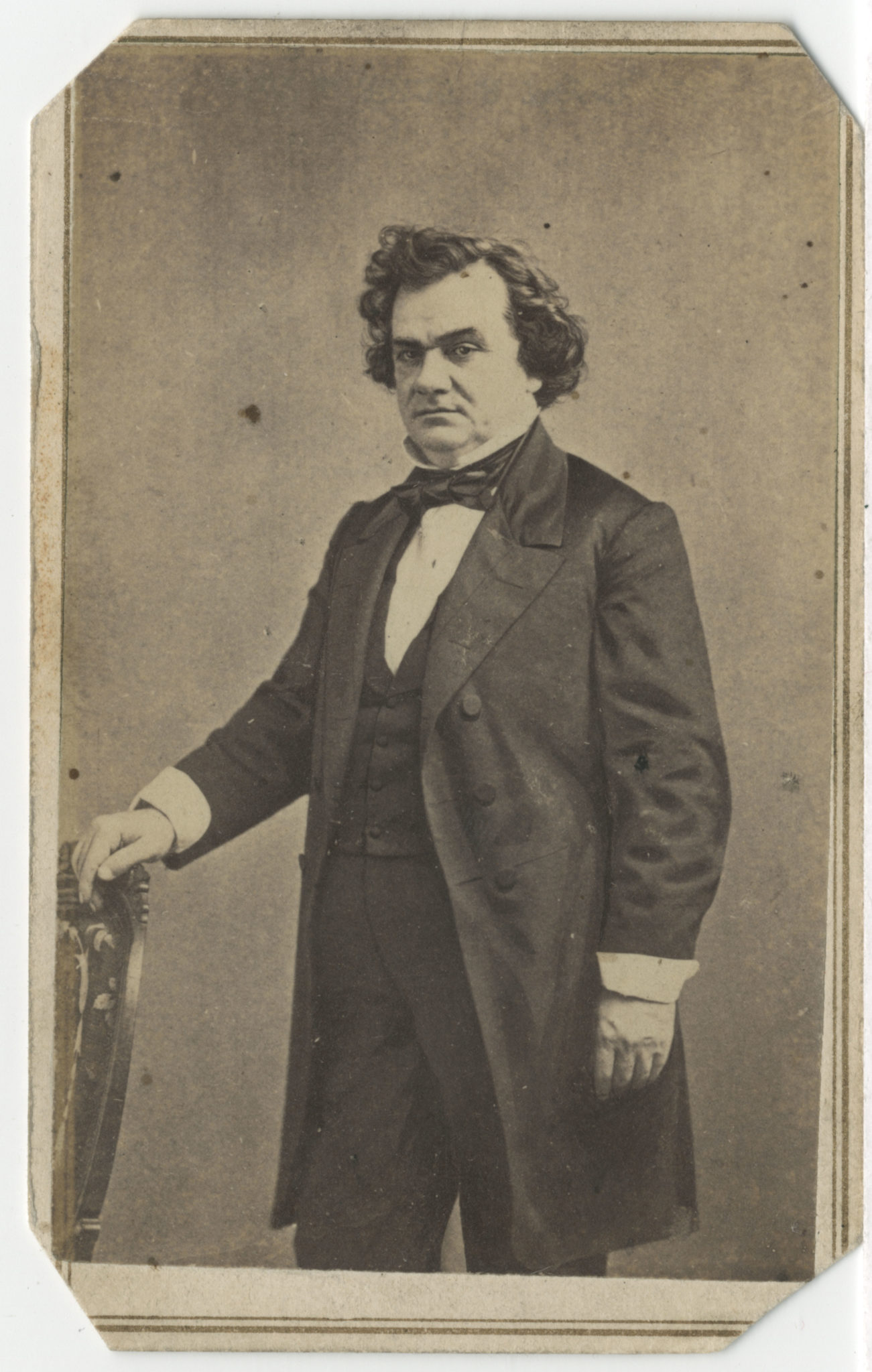

Harold Holzer: Not much of one, really. Certainly the 1830 Webster-Hayne debates over the tariff had long been famous nationwide, but these took place on the floor of the U. S. Senate in Washington, between two public officials, and before a kind of captive audience: fellow senators. As for Lincoln and Douglas, they had exchanged views face-to-face on the stump over the years, debating each other after a fashion, but the idea of participating in a sustained, organized series of “joint meetings” as a major happening seems to me unique to the time, place, and principals of the 1858 race for the U. S. Senate from Illinois. Keep in mind: this was a unique race for other reasons, too, and these factors made the debates possible, maybe even inevitable. There had been no previous senatorial debates for the simple reason that there had never before been senate candidates, or even senate campaigns as we now know them. In the 19th-century, senators were chosen not directly by voters but by state legislatures, which convened a few months after Election Day (technically the following calendar year) to choose senators when vacancies existed. Political parties did not “nominate” Senate standard-bearers; aspirants simply got considered when legislatures met. But having been burned by this maddening system a few years earlier (1855), when, after much shifting of legislative votes he lost a Senate seat he was widely expected to secure, Lincoln told fellow Republicans in 1858 that he would stand for Senate again only if designated as the party’s official candidate at a real convention. His famous “House Divided Speech” actually came at the meeting that so nominated him as the party’s “first and only choice” for the Senate. Even so, Lincoln never faced Douglas on the ballot that year; their debates would be largely ceremonial and symbolic, because the only popular vote that mattered in 1858 was the contest for legislative seats. Nevertheless, Lincoln took to the competition eagerly, seizing every opportunity he could find to confront Douglas. Once the campaign got underway, Lincoln even tried to schedule himself around his opponent’s speaking tours, his goal being to reply to Douglas in public later the same day, or the day after, Douglas’s major appearances. Lincoln’s persistence—which opponents ridiculed—is what, in a way, launched the concept of formal, face-to-face debates as a dignified and convenient alternative.

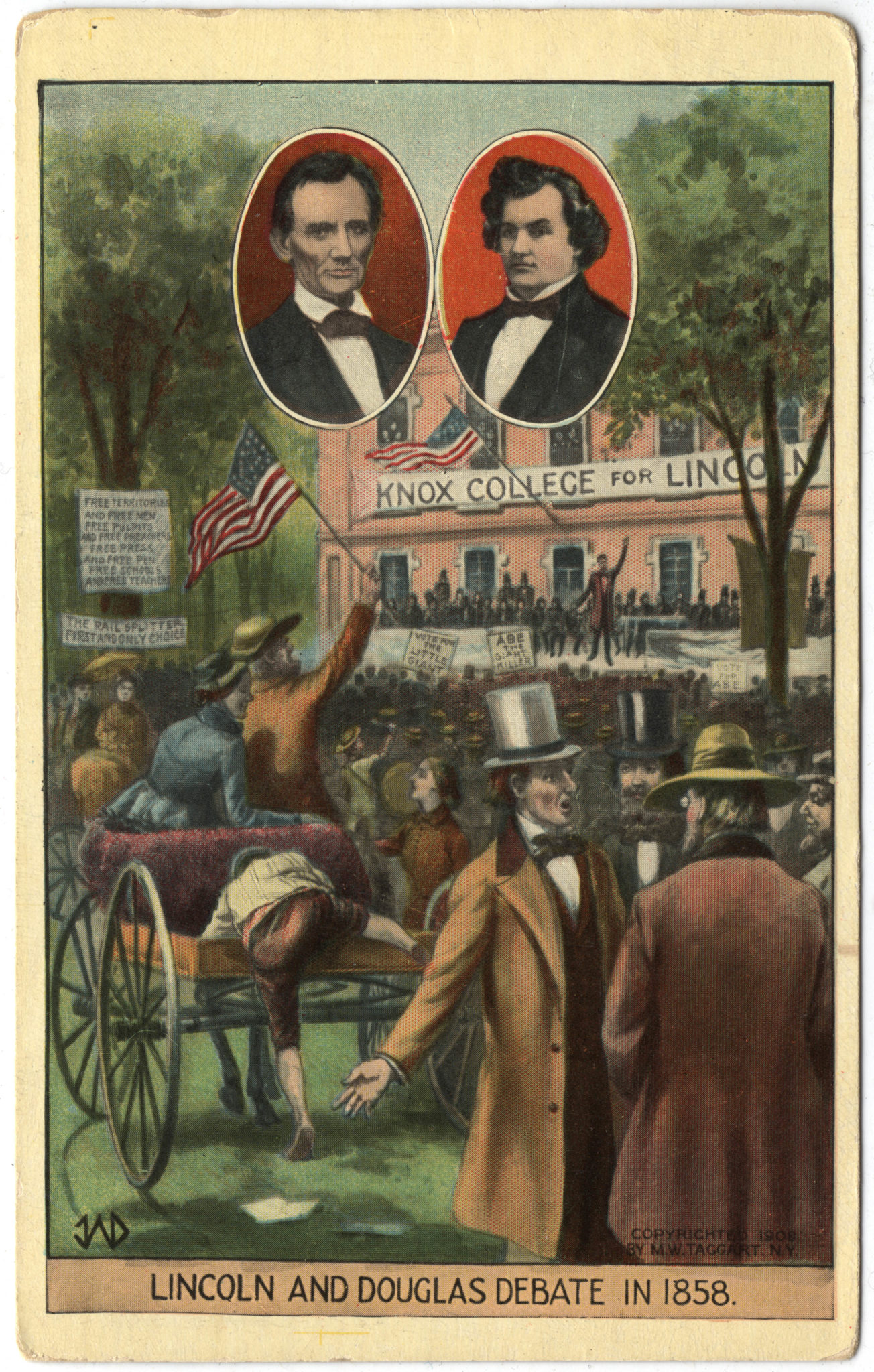

SG: Who suggested the 1858 debates? Were there negotiations as to time/place?

HH: The editors of the pro-Republican Chicago Tribune actually came up with the idea—almost to preserve their man Lincoln’s dignity as he took increasing heat for pursuing the incumbent around the state. Lincoln then wrote a letter formally inviting Douglas to a series of joint appearances. Douglas, better known, better funded, and better scheduled, had nothing to gain and everything to lose by giving Lincoln a bigger platform. But he could find no way to escape the challenge without sacrificing his frontier machismo. It would be akin to declining a duel. Douglas had no choice but to accept. Complicated negotiations did get underway between the two camps. Lincoln wanted dozens of debates. Douglas consented to only nine—one in each of the state’s congressional districts. And then he subtracted two districts because Lincoln had already, annoyingly as far as Douglas was concerned, responded to “The Little Giant’s” orations in both Chicago and Springfield. So in the end, the “net” to which Douglas agreed amounted to just new seven joint meetings. It was a far cry from what Lincoln had wanted, but far better than nothing.

SG: Was there much discrepancy between newspaper reports of the events? Did coverage display political bias?

HH: Discrepancy is a mild word to describe it! Bias is much better. Lincoln’s friends and allies owned the state’s preeminent Republican papers, the Chicago Tribune and Springfield’s Illinois State Journal. Democrats controlled the Chicago Times and the Illinois State Register—in fact, Douglas was an investor in the Chicago paper. It came as no surprise then, and should surprise no one now, that in the Republican coverage of the debates, Lincoln always seemed to win, always sounded fluid and prepared, while Douglas ranted and raved and came off as vulgar and despotic. The Democratic press, however, reported Lincoln as hapless, crude, and often dangerously radical. This divergence extended not only to the news and feature coverage (and opinion-piece editorials, of course), but to the printed transcripts of the debates themselves. I devoted an entire book to this theme 25 years ago, and more recently Douglas Wilson and Rodney Davis took it up in a book of their own. That is to say, I collected and published the long-ignored “reverse” transcripts of the debates: that is, Democratic transcripts of Republican Lincoln’s speeches, and Republican transcripts of Democrat Douglas’s. It’s not a perfect science, but I calculate that these opposition transcripts bring us closest to the unrehearsed words these two titans unleashed on the debate trail than the versions reviewed, polished, and reprinted in sanitized form by friendly editors. So much so that the pro-Douglas Chicago Times complained that the rival Tribune transcriptions contained “whole paragraphs of which Lincoln’s tongue was innocent;” in turn, the Tribune charged that the Times transcriptions contained “mutilations” of Lincoln’s words designed “to mar the beauty of his most eloquent passages, and to make him talk like… a half-witted numbskull.” These were the first political encounters ever “recorded” by stenographers and reprinted in the press—and the results did revolutionize both newspaper coverage of politics and politics itself. But the coverage, and even the transcripts, must be taken with a grain of salt because the press was an owned-and-operated part of the political machine and they not only reported unreliably on the events, they unreliably reprinted the transcripts! In their own time, the debate over which debate records to believe became almost as engrossing as the debates themselves.

SG: Did certain subjects appear in all or most of the debates?

HH: It was slavery, stupid (of course I’m paraphrasing Bill Clinton here, not impugning my friend, the editor of Lincoln Lore, heaven forbid). Yes, the debaters also battled about character, the responsibility of citizens (and legislators) to support a nation engaged in unpopular wars (in this case the late war with Mexico), and other corollary issues. They attacked each other personally. They exchanged “gotchas.” They had a lot of time to expound on any manner of sub-themes. Remember, their presentations were nothing like the ridiculous, one-minute-per-answer debates in vogue today. Each opening speaker had 60 minutes to talk; the rebuttal took 90 minutes, and then the first speaker returned for a final half-hour. These extraordinarily talented orators may have rambled once in a while (to fill time), but they invariably circled back to the big issues of freedom, citizenship, human rights, the Founders, the definition of American opportunity, and the possibility (or impossibility) of racial equality. But all of these themes radiated in a sense from the overarching problem of slavery—from all the evils the institution generated, and all the evils that those opposed to abolition feared its dissolution would ignite.

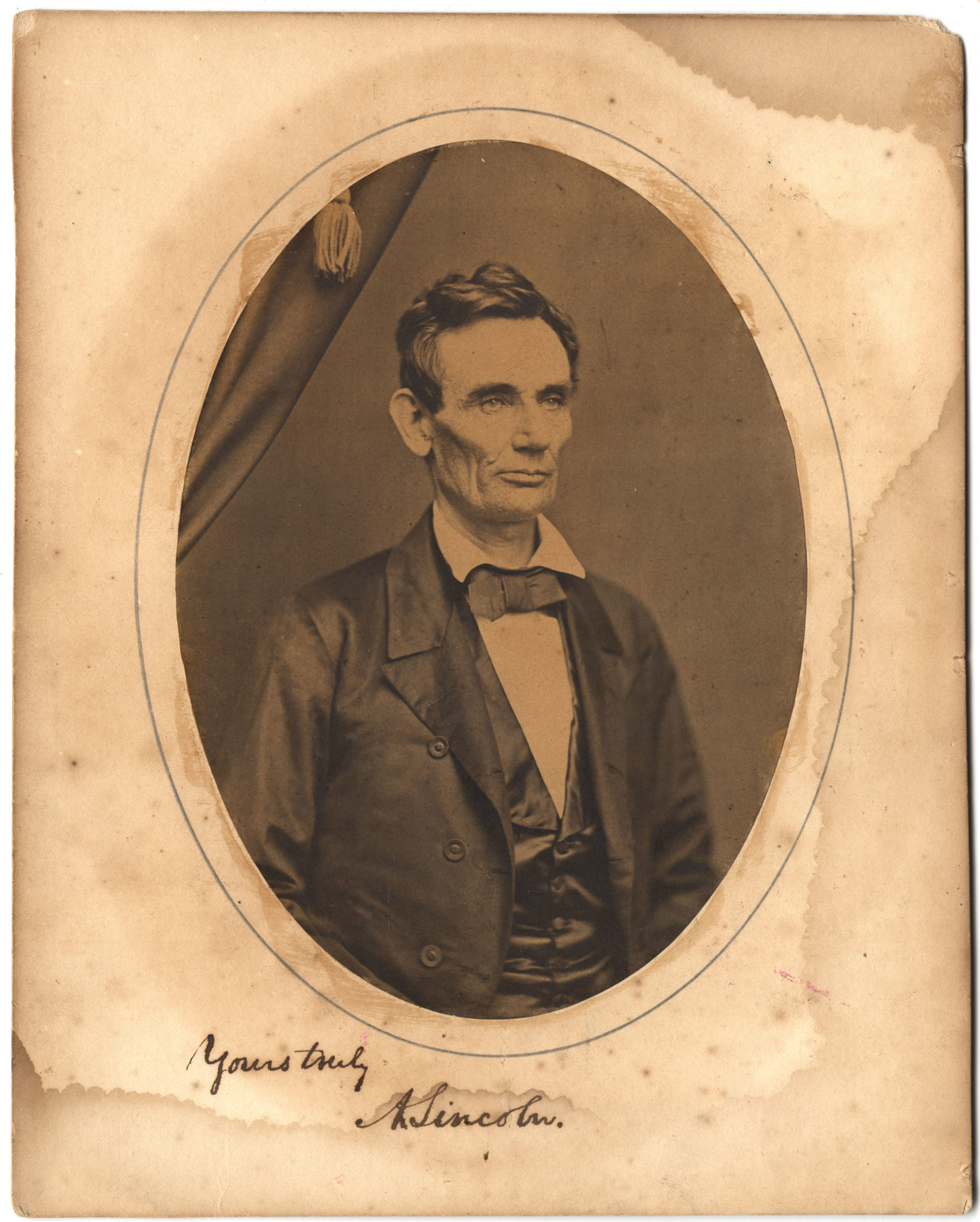

SG: Did reactions to the Debates in part provide some of the interest in Abraham Lincoln which would eventually lead to his Address at Cooper Union?

HH: Absolutely so. Transcripts of, and reports on, the Illinois debates appeared in newspapers all the way to the East Coast, New York included. One typical story reported that excitement in the West ran so deep that “the prairies are on fire.” The notion of these titans confronting each other in public, no holds barred, captured the public imagination nationwide. The word-for-word reprints (as edited, of course) engaged the country in an ever-more urgent discussion of slavery. New York Republicans certainly knew about Lincoln’s debate success, and that is precisely what motivated his hosts to invite him to speak in the city. James Briggs, the New Yorker who sent Lincoln the actual invitation, while a Salmon Chase supporter, had earlier told Lincoln: “There is a deep interest felt here in the Illinois contest.” And when the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant introduced Lincoln on the stage of the Cooper Union’s Great Hall on February 27, 1860, he proved this point by reminding the crowd that Lincoln was “a gallant soldier of the political campaign of 1858,” and a “great champion” of the Republican cause in Illinois.” These were direct references to the debates, and a reminder of how successfully they had introduced the previously little-known Lincoln to voters outside his home state. Cooper Union was the speech that made Lincoln president, as I’ve argued, but the Lincoln-Douglas debates were the events that made Lincoln a prime choice to speak at Cooper Union.

SG: Did Lincoln and/or Douglas mention their Debates in speeches and/or letters which followed?

HH: Oh, yes. First of all, it’s important to note that while we still debate the debates, and who won them, the results were somewhat confusing at the time. The only Republican on the statewide ballot in Illinois that year got more votes than the only Democrat. But the Democrats won enough legislative contests to ensure that Douglas would get chosen for a third term when the legislature met in the winter. So Douglas beat Lincoln. But crushed as he was, Lincoln continued the battle—that is, to control the history and memory of the debates. It was Lincoln who decided to collect newspaper clippings of the transcripts and make them available for publication as a book. Of course he chose the Republican-edited versions of his own remarks. Douglas howled that he was given no chance to re-examine the transcripts for accuracy, while Lincoln made a few further, handwritten editorial changes that survive in the original scrapbook now in the Library of Congress. Lincoln continued to refer to the debates well into the 1860 campaign against Douglas (and others) for the presidency, for when routinely refusing invitations to rallies and new speaking engagements, he urged his hosts to read the debates to get the best idea of his views.

SG: Is there any evidence that Abraham Lincoln realized how important the Debates would be, both to his own career and to students of history in the future?

HH: I think the evidence is in the care he took to create that scrapbook and dispatch a trusted aide, John Nicolay, to carry them to a publisher and get them into print again in more permanent form. I think the proof is in his frequent references to the debates, and to the stories of his giving out books as gifts to visitors who arrived in Springfield during the 1860 campaign, as well as the 1860-1861 interregnum, determined to find out Lincoln’s views. He insisted he would say nothing new; that his positions were on record in the debates, and that they stood the test of time (for the next two years, anyway). His ideas matured over time, of course. His most regrettable debate performance, at Charleston, in which he reiterated what amount to white supremacist views (to be sure not uncommon among mainstream politicians of the day), morphed into something much subtler and more humane during the Civil War. Yes, the Lincoln-Douglas debates launched Abraham Lincoln into the national spotlight, and identified him as a first-class political performer worthy of consideration for even greater things than the U. S. Senate. And while Lincoln himself was wise enough to take advantage of their popularity, he was even wiser to move past them as conditions changed, new opportunities appeared, and his capacity for political and moral growth took hold. The debates may have represented Lincoln’s apogee as a tough campaigner and frontier orator, but they represented only a passing glimpse into his always growing beliefs and ideals.

Harold Holzer is Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. His next book is Monument Man, a biography of the Lincoln Memorial Sculptor Daniel Chester French.