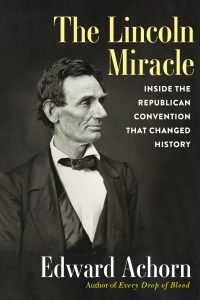

Book Review: Edward Achorn, The Lincoln Miracle

Edward Achorn, The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention that Changed History

Edward Achorn, The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention that Changed History

Book Review by Phelps Gay

Sixty-three years ago, the Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission published a three-volume work called Lincoln Day by Day, A Chronology, 1809-1865, edited by Earl Schenck Miers. An invaluable reference work, it tells us in short factual entries what Lincoln was doing each day of his life, at least so far as could be reconstructed at the time.

In his new book, The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention that Changed History, Edward Achorn also takes a day-by-day approach, from Saturday, May 12, 1860, when people began arriving in the thriving city of Chicago to nominate a Republican candidate for president, through Saturday, May 19, when people began boarding trains to go home. Most were stunned that a relatively obscure former congressman named Abraham Lincoln, instead of the heavily favored New York Senator William H. Seward, had been crowned the nominee.

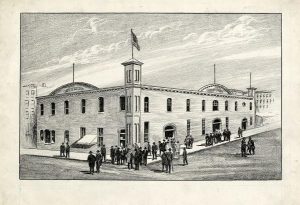

As in his previous book, Every Drop of Blood: The Momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln (2020), Achorn offers us not only a day-by-day but virtually a minute-by-minute account of the proceedings, spiced with vivid sketches of the main characters, descriptions of late-night deals made by political managers, and a near-cinematic picture of the city where these momentous events took place. Indeed, the bustling, dynamic, exciting though occasionally odiferous city of Chicago, whose population had quadrupled over the prior decade, is itself a character in this compelling story, as exemplified by can-do contractors who constructed an enormous barn-like auditorium called the Wigwam in just six weeks.

Although we know the eventual outcome, Achorn recreates the tension and drama surrounding the week’s events as they were experienced by people like David Davis, Leonard Swett, Thurlow Weed, Carl Schurz, and the influential but much-despised (at least by the Seward camp) New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, all of whom did not know how things would turn out. By tradition the candidates stayed home, but Achorn duly notes all letters and telegrams that managers and friends sent to Seward, Lincoln, Edward Bates, Salmon P. Chase, and other aspirants. Lincoln, who loved politics, was divided about whether to show up, saying he felt “too much of a candidate to go, and not quite enough to stay home.”

The book opens with a scene at a train station on a rainy night in October 1858. Lincoln is winding up his campaign against Stephen A. Douglas for the U.S. Senate. Waiting on the platform, the tired candidate encounters a “prim young journalist” named Henry Villard. When it starts to rain, the two men dash into an empty freight car and strike up a conversation. In a “reflective mood,” Lincoln reminisces about his early days clerking in a store in New Salem and shares with the young man his nagging doubts about whether he is “qualified” for the U.S. Senate. He believes he is qualified but confesses that each day he hears a voice saying, “it’s too big a thing for you; you will never get it.” As for the highest office in the land, with a hearty laugh Lincoln says: “Just think of such a Sucker as me as President!”

Finally, the train to Springfield rolls into the station. Achorn writes: “The train disappeared into the darkness, carrying a rising young reporter and a strange politician who was moving toward a heartbreaking defeat in the Senate fight but a future of greatness that not even his ambitious wife could have imagined.” From the endnotes we learn this account is drawn from the Memoirs of Henry Villard, Journalist and Financier, 1835-1900 (1940). Throughout the book, Achorn weaves in facts and stories from a remarkably wide variety of sources—books, letters, diaries, telegrams, interviews, memoirs, newspaper accounts, magazine articles—designed not so much to reflect upon events as to describe how they unfurled in real time and were perceived by those present. In short, the book has a novelistic “you are there” quality, grounded in scrupulous historical research. Asked in a recent interview about his approach in writing this book, Achorn replied: “I tried to look at history as it was happening.”

Among Achorn’s sources is Murat Halstead, a thirty-year-old journalist, editor, and part-owner of the Cincinnati Commercial, whom Achorn describes as “a lively stylist with a sharp eye for detail.” Popping up at regular intervals, at one point Halstead exposes a “devious plot” in the Ohio delegation whereby Benjamin Wade attempts to “wrest political power from his Senate colleague Salmon P. Chase.” This scheme involved adoption of a “unit rule” under which the delegation would commit to vote for Chase on the first ballot and switch entirely to Wade on the second. Upon learning this, Chase supporters “threatened to defect to Seward if the Wade forces persisted,” at which point Wade’s forces “quickly backed off, and instead tried to persuade the influential Halstead to support their man.”

The author paints an excellent portrait of resourceful Judge David Davis, whose mission was to “attempt the impossible” by making his friend president—a daunting task to be sure. On the day Davis arrived in Chicago the morning edition of Harper’s Weekly featured portraits of eleven potential Republican nominees, with William Seward prominently in the center and Lincoln relegated to the bottom row. In the accompanying text on each candidate, Lincoln’s profile was the shortest and appeared last. He was, Achorn writes, considered “the darkest of dark horses.”

To make matters worse, upon arriving at the Tremont Hotel, Davis discovered that no one on the Lincoln team had reserved a room for its headquarters. Taking charge, Davis paid “a premium for the evacuation of certain rooms by private families,” and without anyone electing him to the position, “he at once became the leader of all the Illinois men.” Leonard Swett characterized the “leading trait” of Davis’s character as “unconscious strength.” According to Lincoln, Davis “had that way of making a man do a thing whether he wants to or not.”

And yet, the great irony of the story is that Seward’s prominence became his Achilles heel. Although his 1858 speech on the “irrepressible conflict” between slavery and freedom and Lincoln’s House Divided speech (delivered months earlier) said much the same thing, Seward was more famous than Lincoln, so his words “set off a firestorm” whereas Lincoln’s were “all but ignored outside of Illinois.” Achorn notes that even after Lincoln’s well-received speech at the Cooper Institute in New York City on February 27, 1860, and publication of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, both of which raised his profile, Lincoln was still relatively unknown on a national level. He had no administrative experience beyond running a two-man law office, and he had not held public office since 1849, having lost two subsequent races for the U.S. Senate. Compared to Seward, Lincoln was small potatoes. In fact, party leaders had chosen Chicago as a “neutral site” for the convention, in part because they believed no serious candidate resided in Illinois.

As it turned out, many delegates in Chicago worried that Seward’s “irrepressible” language and his invocation of a “higher law” than the Constitution, especially when viewed in the context of John Brown’s recent attempt to provoke a slave rebellion by raiding a federal armory at Harper’s Ferry, portended the outbreak of civil war. To them, only a more “moderate” candidate, one who could appeal to both the party’s anti-slavery base as well as “swing state” voters who desired to keep the Union together, could prevail against the Democrats in the November general election. A westerner like Lincoln or Bates might fit the bill. “Perhaps more than any other politician,” Achorn writes, “Seward set Southerners on edge.”

In addition, Achorn shows that many delegates were not so much concerned about choosing the “best-qualified” candidate as they were about selecting someone who could help them get elected or re-elected in their home states. Andrew G. Curtin, who hoped to be governor of Pennsylvania, believed a ticket led by Seward “would prove electoral poison” to his chances, as did Henry S. Lane, who sought the same position in Indiana. Regarding these self-interested delegates, Achorn quotes Connecticut journalist Isaac H. Bromley: “They were altogether human,” and whoever believed they were “saints” who “pursued no devious ways” was sorely mistaken. Emphasizing the political nature of the delegates’ task, the pro-Lincoln Chicago Press and Tribune editorialized to arriving delegates: “Constables are worth more than Presidents in the long run, as a means of holding political power. . . . We look to Mr. Lincoln to tow constables and General Assembly [members] into power. . . . The gods help those who help themselves.”

A key part of Lincoln’s strategy was to lay low and position himself as the second choice of most state delegations. To his Ohio friend Samuel Galloway, he wrote: “My name is new in the field; and I suppose I am not the first choice of a very great many. Our policy, then, is to give no offence to others—leave them in a mood to come to us, if they shall be compelled to give up their first love.” This proved to be a sound approach, particularly since Horace Greeley, nursing old wounds suffered (as he perceived it) at the hands of Seward and Weed, was telling everyone Seward could never win the general election.

However, as a Chicago humorist named Finley Peter Dunne would write years later, “politics ain’t beanbag.” Something more than anodyne behavior was needed, and by all accounts Judge Davis and his “Lincoln men” delivered it.

For one thing, Lincoln’s friend Norman Judd was assigned to come up with a seating chart for the delegates. In doing so, he decided to position half the delegates on one side of the massive center stage and half on the other side. He “shrewdly positioned” the entire New York delegation to the right of the podium and surrounded it with other Seward supporters. He then placed the important “wavering delegations” on the other side of the stage, near the Illinois and Indiana camps. The result was that Lincoln’s men “could easily communicate with them during the balloting,” whereas Judd had made it “all but impossible for the Seward men to get over there.” Joseph Medill of the Chicago Press and Tribune, who assisted Judd with this scheme, later confessed, “It was the meanest political trick I ever had a hand in in my life.”

Luck, as usual, played a role. As the proceedings wound down on Thursday, May 17, with approval of a moderate party platform and confirmation that Seward needed only a simple majority of delegates to prevail, the New York senator appeared to be on the verge of victory. Much credit was due to Thurlow Weed, who used his prowess as an experienced “power broker” (and his capacity to provide financial support to delegates who needed it) to his long-time friend’s advantage. Also helpful was Weed’s success in whipping up pro-Seward marching bands outside and screaming crowds inside the Wigwam. Moreover, despite Greeley’s persistent efforts, support for Edward Bates of Missouri was crumbling due to his prior association with the anti-immigrant American (Know-Nothing) Party. Now, with seemingly all momentum on Seward’s side, it was time to vote.

But it was after 6 p.m., and some tired and hungry delegates moved to adjourn, preferring to vote the next morning; others, also tired and hungry, wanted to vote right away. At that point the convention chair announced that the presidential tally sheets “are prepared but not yet at hand, but will be in a few minutes.” According to Achorn, “the prospect of further delay took the spirit out of the famished delegates,” and they decided to adjourn for the evening.

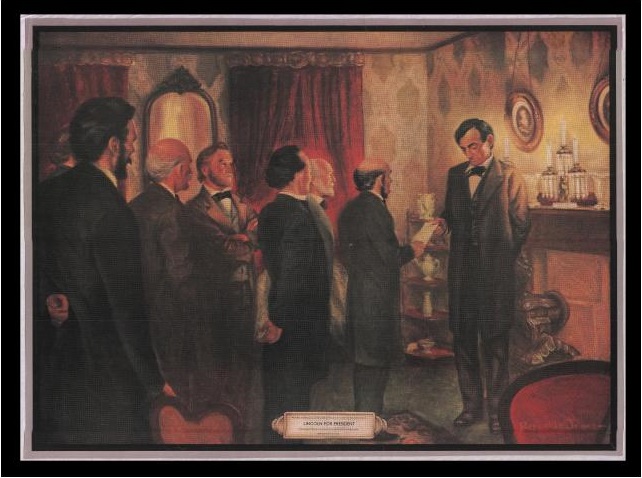

Given a reprieve, Lincoln’s men used the remaining time well. Upon receiving a note from Lincoln urging his team to “make no contracts that will bind me,” Judge Davis brushed it aside. “Lincoln ain’t here,” he said, “and don’t know what we have to meet, so we will go ahead as if we hadn’t heard from him, and he must ratify it.”

To shore up Indiana’s support Davis and company offered former Congressman Caleb B. Smith a cabinet seat—Secretary of the Interior. Later that night this deal apparently helped a hastily-formed “committee of twelve”—three men each from the Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania delegations—tentatively settle on Lincoln as their alternative to Seward, but only if New Jersey would agree to give up on former Senator William L. Dayton and Pennsylvania would abandon Senator Simon Cameron. (This was all under the assumption that their respective delegations would go along.) Still later that night, four Lincoln men (Davis, Swett, Stephen T. Logan, and William P. Dole) met with Pennsylvania leaders at the Tremont House in an effort to seal this deal. When it appeared they had been successful, journalist Joseph Medill asked Davis how he did it. “By paying their price,” Davis replied. That price included a position for Cameron in Lincoln’s cabinet.

Here it should be noted that Cameron enjoyed a checkered reputation for honesty and fair dealing, to put it mildly. Sarcastically, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens later conceded he didn’t think Cameron “would steal a red-hot stove.” Cameron denied making a deal with Lincoln’s men, protesting that he stood by Seward while Davis and Swett “bought all my men.” The evidence, Achorn notes, suggests Cameron was both aware of the deal and approved it.

Still, as Friday morning, May 18, dawned, the Seward forces remained highly optimistic. A thousand men, “wearing their silk Seward badges,” marched in the streets toward the Wigwam behind the “brilliantly uniformed” Dodworth Band of New York. The wily Weed planned to “fill the building with men who would scream at the mere mention” of Seward’s name. Alas, as Murat Halstead observed, they “protracted their march too much,” because when they arrived at the 11,000-seat auditorium, many of them couldn’t get in. Why? According to one account, certain young men supporting Lincoln spent Thursday night printing “counterfeit tickets” so that on Friday morning three hundred Lincoln supporters gained admission to the Wigwam, keeping the same number of noisy Seward enthusiasts out.

As we know, on the first ballot Seward, needing 233 votes, fell short with 173 ½ to Lincoln’s 102. On the second ballot, the gap narrowed considerably, with Seward at 184 ½ and Lincoln 181. On the third, the delegates closed ranks behind their new nominee, Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. Graciously, William M. Evarts, chairman of the New York delegation, moved that Lincoln’s nomination be made unanimous, but as Achorn notes it took a quite a long time before Seward and his Empire State friends could even begin to digest the fact that the “darkest of dark horses,” an obscure lawyer from a small town in a western state, had become the Republican nominee for the presidency of the United States.

In the end, what distinguishes this fine book, as was the case with Every Drop of Blood, is the creative manner of its telling. Part historical narrative, part non-fiction novel, part screenplay, The Lincoln Miracle is suffused with drama. Scenes are colorfully set; people are physically described, such as Lincoln’s friend Jesse K. Dubois, with his blue eyes and auburn hair. We learn what people wore, such as Greeley’s worn-out white linen coat, battered beaver hat, and dirty boots. We learn how the trains belched, how factories “filled the sky with an acrid haze,” and how the sluggish Chicago River smelled. Inside the Wigwam, we learn not only about the delegates but about cloth bunting, unfinished wood, and gaslights flaring. (Historian Bruce Catton later wrote “it must have been one of the most dangerous fire traps ever built in America.”) We even learn what Judge Davis could see outside the window of his Tremont Hotel room—namely, a huge sign with one word: SEWARD.

In sum, Edward Achorn bears a striking resemblance to one of his characters—reporter Murat Halstead, “a lively stylist with a sharp eye for detail.” He is something of an artist-entertainer, yet one who has clearly done his historical homework. If we are lucky, we will hear from him further.

Phelps Gay is an attorney from New Orleans who currently serves as chair of the Louisiana Supreme Court Historical Society.