Book Review: William E. Bartelt and Joshua A. Claybourn, Abe’s Youth; J. Edward Murr, Abraham Lincoln’s Wilderness Years

William E. Bartelt & Joshua A. Claybourn: Abe’s Youth: Shaping the Future President

J. Edward Murr, edited by Joshua Claybourn: Abraham Lincoln’s Wilderness Years: Collected Works of J. Edward Murr

Review Essay by Andrew F. Lang

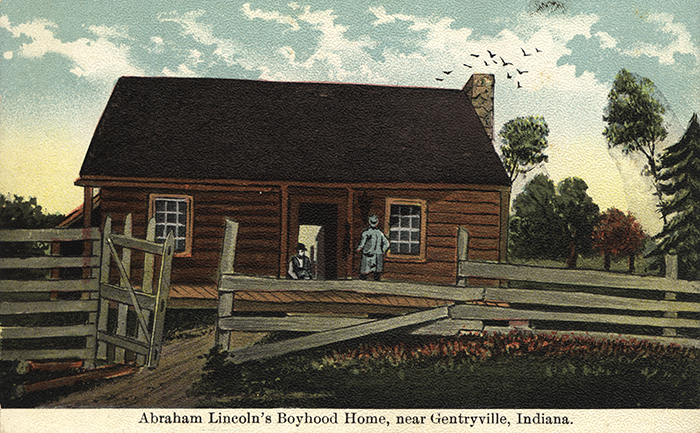

The “Lincoln legend” goes something like this. Born in 1809 to impoverished Kentucky parents whose earthly possessions consisted of little more than a small log cabin, Abraham Lincoln moved with his family in 1816 to Indiana. There, the Lincoln flock labored in obscurity, eking out a subsistence living amid the tangled thickets of the American frontier. Burdened by the death of his beloved mother and sister, and deprived of formal education, an ambitious Abraham longed to escape his gloomy, unfulfilling reality. In 1830, his father Thomas again moved the family, this time to the Illinois prairie. But opportunity struck. At twenty-one years old, Abraham broke from his clan. He vowed never to return to a life of fruitless toil. With a sharp mind, unmatched wit, and enviable work ethic, Lincoln mastered the law and matured into a shrewd politician. Seats in the Illinois state legislature and the United States Congress enhanced his public confidence. With the advent of an irreconcilable sectional crisis during the 1850s, Lincoln emerged as a leading spokesperson of the antislavery cause. The American people then elevated him in 1860 to the presidency as the best hope to contest disunion and civil war. The most unlikely but also the most authentic of American presidents, Lincoln sacrificed his life to liberate an enslaved people and save his beloved Union.

The myth continues. Guided by his better angels, Lincoln had transcended the humble obstacles of his birth. Indeed, he rarely spoke of his roots. “It is a great piece of folly to attempt to make anything out of my early life,” Lincoln informed a Republican campaign biographer in 1860. “It can all be condensed into a single sentence, and that sentence you will find in Gray’s Elegy: ‘The short and simple annals of the poor.’ That’s my life, and that’s all you or any one else can make of it.”

When Lincoln’s closest confidants chronicled his life, they echoed what appeared to be their dear friend’s modesty. But in so doing, they salved their own embarrassment about their hero’s backward youth. Ward Hill Lamon pictured the inhabitants of Southwestern Indiana as shoeless, primitive folk who found solace in the bottle. William Herndon denigrated the Hoosier state as an uncultured, retrograde boondock. John Nicolay and John Hay’s enormous ten-volume biography featured a single, brief chapter on the Indiana years. Reducing Lincoln’s contemporaries to a people “full of strange superstitions,” Nicolay and Hay fled Indiana as quickly as possible before conferring sainthood upon their martyred chief.

Never satisfied with the status quo, historians often question anew subjects of old, yielding transformational revisions to conventional wisdom. Between 1920 and 1939, an aspiring cluster of Indianans founded the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society (SWIHS) and charted the Lincoln Inquiry. Their tireless energy produced hundreds of interviews with people who knew the Indiana Lincolns, grew up with the young Abraham, and attested to the rich frontier upbringing that shaped the future president. The SWIHS comprised amateur historians and genealogists who delivered nearly 400 presentations and authored more than 200 papers to recreate Lincoln’s youth. Likewise, a native of Corydon, Indiana, Rev. J. Edward Murr (1868–1960), came of age with Lincoln’s cousins. With unparalleled access to Lincoln’s earliest acquaintances and unmatched knowledge of the Indiana environs, Murr compiled an immense archive of interviews, writings, and manuscripts.

A vast majority of the SWIHS’s and Murr’s work was never published. Though much of the documentation remained scattered in various state archives and libraries, their materials shaped influential biographies by Ida Tarbell, Albert J. Beveridge, Mark E. Neely Jr., and Michael Burlingame. These authors emphasized Indiana’s abiding sway on Lincoln’s intellectual development and budding political outlook. Now, thanks to the superb talents of editors William E. Bartelt and Joshua A. Claybourn, much of the material from the SWIHS and Murr are published in accessible annotated volumes. Alongside William Herndon’s essential interviews with Lincoln informants, Bartelt and Claybourn’s editions present the most comprehensive, complex, and colorful entryway into Lincoln’s mysterious Indiana upbringing.

As with all reminiscences, readers should exercise caution when engaging the memories and varied purposes of informants. Indeed, the Lincoln Inquiry aimed to rehabilitate the sullied image of Southwest Indiana as an anti-intellectual, backward pit that Lincoln would have to conquer on his path to greatness. When approached with dispassionate care, however, both the SWIHS collections and Murr’s writings convey an overwhelming sense that Lincoln the successful lawyer, Lincoln the skilled debater, and Lincoln the moral statesman, all grew from the Lincoln of the streams and rivers, the woodlots and hamlets, of frontier Indiana. As coeditors of Abe’s Youth: Shaping the Future President, Bartelt and Claybourn culled the best samples from the Lincoln Inquiry’s work. In the single-edited Abraham Lincoln’s Wilderness Years, Claybourn compiled chapters from Murr’s unpublished biography, his essays published between 1917 and 1918 in the Indiana Magazine of History, and his correspondence with Beveridge. Both works represent a masterwork of documentary editing. The editors correct falsehoods and misrepresentations. And they provide learned commentary on even the most minute but essential facts.

Taken together, the Lincoln Inquiry and Murr tell a story of roughhewn but idyllic Indiana communities, bustling with economic and intellectual energy, peopled by curious and determined citizens. Bound by kinship and friendship, Lincoln developed a kind manner, a gentle spirit, a restrained disposition, a talented ambition. Neither the informants nor the writers deify Lincoln, ascending him high above the river towns and beyond the broad prairies of his common youth. They love him, to be sure. But he was one of them, and they an enduring part of him. Indiana gave Lincoln life. And when he died, a part of that proud community also died. Though as Lincoln himself believed, the honored dead may no longer breathe, but their spirits never perish from the earth. The memory of his Indiana days conceived and dedicated the Lincoln Inquiry and J. Edward Murr’s devotion, to which the latest generation remains indebted.

* * *

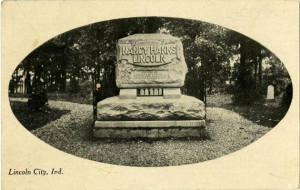

In 1816, the very year that Indiana joined the Union, the Lincolns settled in Spencer County in the southwestern part of the state known as “the pocket.” From ages 7 to 21, Lincoln lived one-quarter of his life in the region. Between 1816 and 1830, his world was shaped by personal trial. His mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died when Abraham was only nine years old. His sister, Sarah Lincoln Grigsby, perished when he was a teenager. Though he knew Nancy for but a short time, Lincoln later recalled, “All that I am or hope to be I get from my mother—God bless her.” His father, Thomas, soon remarried, bringing into the family the widow Sarah Bush Johnston and her three children. Lincoln adored Sarah, and she bestowed a motherly love of which Lincoln had been deprived at a young age. The Lincoln Inquiry and Murr both paint a relatively happy childhood. Popular memory—enhanced by some of the SWIHS essayists—nevertheless denigrates Thomas as an uninspiring ne’er-do-well who formed a tense, distant relationship with his son. Yet Murr disagreed. He paints Thomas as a man of character, decency, and honesty, a man who committed himself to his family and faith, a man who subordinated his self-interest to the broader community. In this vein, Murr portrayed Thomas as “father of the [very] president” in whom we identify similar traits.

The Lincoln Inquiry and Murr portray Lincoln’s Indiana years as positive and constructive. We see Lincoln learning the values of cooperation and friendship, of local associations and civil society. He was surrounded, T. H. Masterson spoke in his 1928 SWIHS paper, by a people “profoundly religious, almost mystic in their belief that right would prevail.” But later in life, Lincoln expressed ambivalence toward his years in “the pocket.” When he returned to Indiana in 1844 to campaign for his political idol, Henry Clay, Lincoln ventured to his boyhood region. And though he reflected on his attachment to place and people, to love and fondness, he also dwelled on the pain and the personal loss he experienced as a boy. He fixated on the immovable force of history, of perplexing circumstance and necessity. Might the passage of time, he wondered, cure the aching memories of yesteryear? Was his early life of poverty and strain predestined and determinative?

His 1844 trip inspired a heartrending poem that harked back to the Indiana days. “I range the fields with pensive tread, / And pace the hollow rooms; / And feel (companions of the dead) / I’m living in the tombs.” He continued: “Now fare thee well: more thou the cause / Than subject now of woe. / All mental pangs, but time’s kind laws, / Hast lost the power to know. / And now away to seek some scene / Less painful than the last.” The poem agonizes on the haunting memory of Matthew Gentry, a dear friend of Lincoln’s, who suffered a manic collapse when Abraham was sixteen. Even as a young man, Lincoln believed that only by harnessing his mind, controlling his passions, and resorting to reason would he resolve his destitute condition. Lincoln saw in Matthew’s deterioration the devastating loss of mental fortitude, the sole source of individual mobility and personal sovereignty.

And herein resides the great value of the Lincoln Inquiry and Murr’s literature. They demonstrate how Indiana stuck with Lincoln long after he departed the Hoosier state. As he wrote in 1846, “That part of the country is, within itself, as unpoetical as any spot of the earth; but still, seeing it and its objects and inhabitants aroused feelings in me which were certainly poetry.” Here was a brief expression of gratitude, of affection, a realization that something profound had occurred in that unknown corner of the Midwest. Lincoln sensed that he had been placed for a reason in rural Indiana. There, he was a young citizen living on the edge of a young republic. As the fledgling boy matured to manhood, so too did the youthful Union strengthen in stature. As man and nation grew in tandem, they each remained uncertain of their destiny, but each searched for a moral core, desirous to know their higher purpose.

The Lincoln Inquiry and Murr insist that we can see planted in the silty Indiana soil the seeds of Lincoln’s mature thought: his obsession with education, his faith in the individual’s right to rise in a free society, his belief in the law and mediating institutions, his search for spiritual and civil order, his quest for personal peace amid waves of melancholy. Lincoln’s Indiana acquaintances and associates appear to have left a lasting influence on his young life. From the antislavery sermons of Adam Shoemaker to the industriousness of local merchant James Gentry, and from the unmatched law library of John Pitcher to the ferry operator James Taylor, with whom Lincoln traveled the Mississippi River in 1828, a diverse host of influences paved Lincoln’s future paths. About these noteworthy personalities, Bess V. Ehrmann, the fourth president of the SWIHS, wrote in her 1925 paper, “His neighbors were largely clear-minded, unpretending men of common sense, whose patriotism was unquestionable.”

Like most members of the Lincoln Inquiry, Ehrmann transposed Lincoln’s iconic stature back onto his childhood. But there is a convincing, substantial degree of truth in her observation. Dozens of writers and informants documented the rich networks of communication and news that traveled among “the pocket’s” small communities. Country stores bustled with commerce and politics. And Lincoln himself borrowed books, forged a reputation for dependable labor, and exhibited a strange curiosity for the world around him. How else, Ehrmann asked, could a twenty-three-year-old Lincoln be equipped to announce his candidacy for the Illinois General Assembly in 1832, a mere two years after leaving Indiana? To the citizens of Sangamon County, Illinois, Lincoln’s first political announcement brims with themes derived from his life in Indiana: the West’s need for internal improvements, pleas for popular reverence of the law, and the necessity “that every man may receive at least, a moderate education.” This budding politician of the western prairie even admitted that “his peculiar ambition” was to be “esteemed of my fellow men.”

One can little doubt the sincerity in Lincoln’s entreaty. He trusted his abilities, but he well understood the limits imposed by his frontier condition. Though the Lincoln Inquiry touted all the seeming benefits afforded by the bustling life of Southwestern Indiana, Lincoln was still a poor, penniless, beginner in the world. That unenviable condition presented Lincoln with a choice: either harness a determination to rise or strive in obscurity. Both paths required hard work. But work was not passive. Labor in a free republic required knowledge, it required desire, it demanded the hope of becoming something better. “His youthful ambition to rise in the world,” Murr noted, “was native, domineering, and irresistible.” As difficult as his early life was, Lincoln was a free citizen, unburdened by the suffocating yoke of enslavement and enslaving. He learned at an early age that he possessed the natural right to dream ambitious dreams and pursue happiness as he understood it. A free citizen maintained an obligation to improve one’s condition and to ensure the same equal right for others. Lincoln never abandoned this enduring democratic faith. It was a faith that he later brought forth to the nation.

Andrew F. Lang is associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. He is the author most recently of A Contest of Civilizations: Exposing the Crisis of American Exceptionalism in the Civil War Era (UNC Press, 2022), which was a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize. A recipient of the Society of Civil War Historians’ Tom Watson Brown Book Award, he is now writing an intellectual and cultural biography of Lincoln’s nationalism.