Mystery Solved: Why the Harper’s Weekly Close-Up of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Credited A Photo By Alexander Gardner

Mystery Solved: Why the Harper’s Weekly Close-Up of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Credited A Photo By Alexander Gardner

Mystery Solved: Why the Harper’s Weekly Close-Up of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Credited A Photo By Alexander Gardner

Harold Holzer

Students of mid-nineteenth-century image-making know that engravers and lithographers of that period—along with painters and sculptors—had become increasingly dependent on the medium of photography to provide source material for portraits. One of the great beneficiaries of this phenomenon was Abraham Lincoln, who had only limited time to pose formally for artists, but did sit for many photographs destined for adaptation into paintings, busts, and statues. Decades earlier, Mathew Brady had told Samuel Morse that he planned to make photography “as far as possible an auxiliary to the artist.”[1] That is precisely what he, and others, did.[2]

Appropriately, photographers often received credit for the images that inspired graphic artists. When periodicals like Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper adapted photos into woodcut engravings—especially originals by celebrity photographers like Brady and Alexander Gardner—they often acknowledged the source material: “From a photograph by Brady” or “From a Photograph by Gardner.” No doubt, the photographers earned not only credit, but remuneration, for providing models for woodcuts.

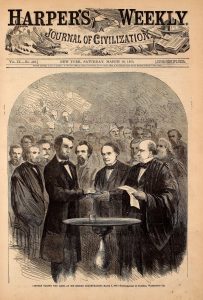

Yet not all such attributions make sense to modern eyes. And one of the most stubbornly puzzling of all is the close-up illustration, published on the cover of Harper’s Weekly two weeks after the 1865 inaugural, and entitled: Lincoln Taking the Oath at his Second Inauguration, March 4, 1865—Photographed by Gardner, Washington.[3]

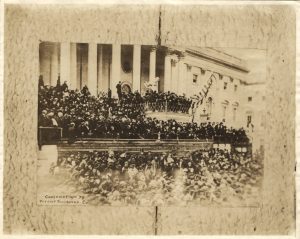

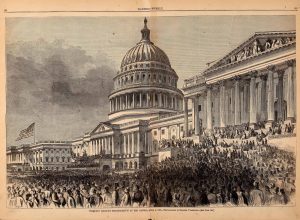

But how to explain this credit line? Yes, Alexander Gardner had indeed set up his camera outside the U. S. Capitol that momentous day. From the edge of the crowd, he made a series of remarkable pictures, some showing Lincoln seated on the East Portico waiting to be introduced, and the most famous of them showing him standing before a small lectern delivering his iconic Second Inaugural Address.[4] But all these images were exposed from a significant distance, with Lincoln’s features unavoidably blurred. So how could Gardner possibly have moved his camera close enough—quickly enough—to so clearly capture Lincoln, hand on bible, taking the presidential oath from Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase? How had Gardner managed to record Lincoln’s expressive face, along with such onlookers as outgoing Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and Lincoln’s private secretaries, John G. Nicolay and John Hay? No photographic source has ever been unearthed for the woodcut, so we have long assumed it never existed, even as we hoped it might instead be lost and waiting to be re-discovered.

Purely in chronological terms, the chance to make such a photo could have presented itself. In those days, an incoming president gave his inaugural address first, and only then took the oath of office, the opposite of the ceremonial procedure today. But Gardner was simply too far away to position himself for a close-up of the swearing-in so soon after photographing Lincoln delivering his brief speech from afar.

Tellingly, Gardner had failed to manage just such a feat back in 1863. That November 19, he succeeded in taking some crowd shots from the back of the throng attending the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg—but then proved unable to get his camera close enough to the speakers’ stand to capture Lincoln delivering his Gettysburg Address. If we are really meant to believe the Harper’s photo credit from the inauguration, then how had Gardner managed to be in two places at once on March 4, 1865?

For decades, I had simply assumed that the credit line on the inaugural engraving was gratuitous—added because the public likely knew that Gardner had been present at the inauguration and might believe he could be responsible for the close-up. The attribution certainly made marketing sense for Harper’s, which had long boasted of its access to work by prominent camera artists.

For decades, I had simply assumed that the credit line on the inaugural engraving was gratuitous—added because the public likely knew that Gardner had been present at the inauguration and might believe he could be responsible for the close-up. The attribution certainly made marketing sense for Harper’s, which had long boasted of its access to work by prominent camera artists.

There the matter rested—at least for me—until Civil War photography expert Bob Zeller contacted me in April 2021 to ask anew if I could explain the Gardner credit on the oath-taking illustration. As Zeller pointed out: “The close-up, a well-known engraving, shows an impossible camera position basically in midair… . Could the engraving be a representation of the heart of a ‘lost’ Gardner photograph? One would think Gardner would have wanted to photograph the swearing-in, too. Or perhaps the engraving is misattributed to a Gardner photograph.”

The inquiry inspired me to think afresh about this mystery. And because of Zeller’s prodding, I gave the problem another look. This time the light finally dawned. The answer was always there—in reverse. No, Gardner did not use a dolly crane or some other yet-to-be-invented conveyance to zoom-in on Lincoln’s oath-taking. But no, the Harper’s woodcut wasn’t exactly misattributed, either. Here is what happened.

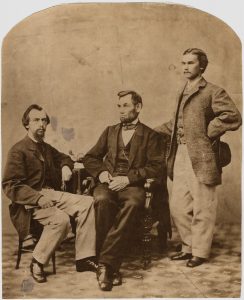

Gardner produced no adaptable close-up of the swearing-in on March 4, 1865. So Harper’s, coveting such an illustration for the cover of its inauguration issue, resorted to image manipulation to produce it. The New York weekly simply turned to an indoor photograph Gardner had made at his Washington studio back on November 8, 1863. That day, Gardner took several magnificent portraits of Lincoln—at the request, it might be noted, of yet another artist who needed photos as source models: sculptor Sarah Fisher Ames.[5] And then, as John Hay testified in his diary, “Nico[lay] & I immortalized ourselves by having ourselves done in a group with the Prest.”[6] Therein lies the long-overlooked clue to the 1865 inauguration woodcut. It was based on an outdated 1863 photo—yes, by Gardner—of Lincoln with Nicolay and Hay. [7] Harper’s Weekly had actually published an altered version of that group pose previously—a woodcut published in 1864—so there can be no question that its artists had access to it.[8]

When one re-examines Harper’s swearing-in engraving in this light, one immediately recognizes its obvious debt to the 1863 studio shot. To fashion its 1865 woodcut, a Harper’s engraver simply copied the three individual 1863 photos and placed them within the new scene, without carving them in reverse, as faithful reproductions required. As a result, the figures appear in the inaugural tableau as mirror images of their original source—effectively disguising them for readers of the day—and for all observers since. Harper’s simply deconstructed Gardner’s 1863 studio shot and reconstructed its individual elements for its inaugural cover, inventing the overall design from scratch, or perhaps from a reporter’s personal observation.

Now we know why the resulting Harper’s close-up of Lincoln bears so little resemblance to the haggard president’s actual appearance in March 1865. As photos from that winter reveal—February 5 (also by Gardner) and March 6 (by Henry Warren)—Lincoln had cut his hair short and trimmed his beard back to a near-goatee before the inaugural.[9] To witnesses at the second inaugural, the President’s face looked thin and careworn. So why had Harper’s decided not to adapt Gardner’s more up-to-date February 5 photos? One can only speculate that the “real” Lincoln was simply not ready for his close-up: he looked so painfully gaunt in the last few weeks of his life that Harper’s apparently preferred to show him as he had appeared earlier.

Hence its inaugural cover presented a Lincoln with a fuller beard and a neat pompadour, looking robust, smiling benignly and casting his eyes slightly downward—precisely as he had at Gardner’s studio two years before. Harper’s would show Lincoln standing, not seated as he had posed at the gallery in 1863, now cleverly superimposed onto a blow-up of the body Gardner photographed on inauguration day from afar. As for the presidential aides who stand in the background in Harper’s, they, too, are precise mirror-image copies of Nicolay and Hay as they had appeared at Gardner’s alongside their boss—but now separated from the original pose, and manipulated to float within the knot of people surrounding Lincoln outside the Capitol.

Hence its inaugural cover presented a Lincoln with a fuller beard and a neat pompadour, looking robust, smiling benignly and casting his eyes slightly downward—precisely as he had at Gardner’s studio two years before. Harper’s would show Lincoln standing, not seated as he had posed at the gallery in 1863, now cleverly superimposed onto a blow-up of the body Gardner photographed on inauguration day from afar. As for the presidential aides who stand in the background in Harper’s, they, too, are precise mirror-image copies of Nicolay and Hay as they had appeared at Gardner’s alongside their boss—but now separated from the original pose, and manipulated to float within the knot of people surrounding Lincoln outside the Capitol.

Mystery solved, composite parsed, and photo credit explained. The Harper’s engraving of Lincoln taking the oath at his second inaugural is indeed from a photograph by Gardner. But it was a photograph taken 16 months before the great speech, and ironically, only days before Lincoln had delivered an earlier masterpiece of oratory.

Harold Holzer is the Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College.

This article was originally published in the journal Battlefield Photographer, Vol. XIX, No. 2 (July 2021).

[1] Quoted in Van Deren Coke, The Painter and the Photograph: From Delacroix to Warhol Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1964), 25.

[2] For examples, see Harold Holzer, Mark E. Neely Jr., and Gabor S. Boritt, The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print (New York: Scribner’s, 1984).

[3] Harper’s Weekly, May 18, 1865.

[4] For examples, see Philip B. Kunhardt III, Peter W. Kunhardt, & Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Looking for Lincoln: The Making of an American Icon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 473-474.

[5] As Hay noted in his diary: “Went with Mrs. Ames to Gardner’s Gallery & were soon joined by Nico[lay] and the Pres[iden]t.” See Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press,1997), 109. For the Ames bust, see Harold Holzer, “Sculptures of Abraham Lincoln from Life,” Magazine Antiques 113 (February 1978): 388, 391.

[6] Burlingame and Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House, 109.

[7] Lloyd Ostendorf, Lincoln’s Photographs: A Complete Album (Dayton: Rockywood Press, 1998), 142.

[8] Harper’s Weekly, June 11, 184.

[9] Philip B. Kunhardt III, Peter W. Kunhardt, and Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Lincoln, Life-Size (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 150-155, 181.