Lincoln & The 1862 Minnesota Sioux Trials

Lincoln & The 1862 Minnesota Sioux Trials

Lincoln & The 1862 Minnesota Sioux Trials

Burrus M. Carnahan

One hundred and fifty years ago the Upper and Lower Sioux Reservations were located in southwestern Minnesota on a thin strip of land on the south side of the Minnesota River. After their traditional hunting grounds had been depleted by fur trapping and white settlement, the Dakota, or Sioux, [1] ceded the rest of southwestern Minnesota to the U.S. government via a series of treaties in exchange for annual monetary payments. The government payment was usually distributed in June. In 1862, however, it was late in arriving.

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men from the Lower Sioux Reservation went hunting for game. One of them found some eggs in a hen’s nest near a white settler’s farm. When another warned that taking the eggs would cause trouble with the whites, he was accused of being a coward, afraid of the white men. Accusations and denials flew back and forth, and tempers rose. In the end, to prove they were not afraid of them, the four hunters killed five white settlers at random, three men and two women.

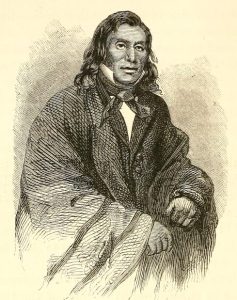

When the young men returned to the Lower Reservation the next morning, the Dakota leaders realized that they would have to either turn them over to the U.S. and Minnesota authorities or go to war. The Minnesota Dakota had suffered years of dishonest treatment at the hands of white traders and government agents. The money due them by the treaties was two months overdue with no guarantee—or faith that it would ever arrive. Although several Dakota leaders pointed out their dismal odds of winning a war against the United States, and accurately predicted that their people would lose their remnant of land in Minnesota as a result of waging the war, the contentious debate nevertheless resulted in the final decision to go to war, under the leadership of a chief named Little Crow.[2]

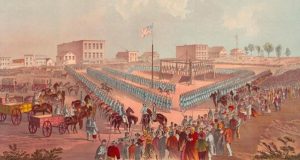

Over the next week, Little Crow led the main body of Dakota warriors in attacks on the government Indian Agency at Redwood, the town of New Ulm and the Fort Ridgely army post. Smaller Dakota bands fanned out to attack homesteads and settlements. Adult men were generally killed, but women and children were often taken captive. Another battle occurred on September 2, when Little Crow’s force attacked a detachment of soldiers from the 7th Regiment of Minnesota Volunteer Infantry camped at Birch Coulee. According to a contemporary historian, the brief war killed 42 Dakota, 93 Minnesota Volunteer soldiers and 644 white civilians.[3]

By Civil War standards the battles with Little Crow were small skirmishes, with fewer than a thousand men engaged on each side, but they terrified the people of Minnesota. On August 21, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey telegraphed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that the “Sioux Indians on our western border have risen, and are murdering men, women, and children.”[4] When the uprising broke out, Lincoln’s secretary John Nicolay and U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs William P. Dole were both in Minnesota to negotiate a treaty with the Chippewa. On August 27 they and Minnesota Senator Wilkinson sent a joint telegram to President Lincoln asserting that they were “…in the midst of a most terrible and exciting Indian war. Thus far the massacre of innocent white settlers has been fearful. A wild panic prevails in nearly one-half of the State.”[5]

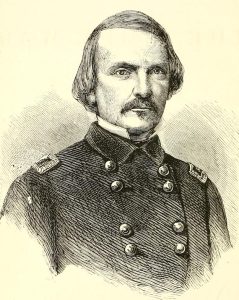

In response, on August 19 Governor Ramsey appointed Henry H. Sibley as a colonel of Minnesota Volunteers and ordered him to lead an expedition against the Indians. Sibley, a wealthy fur trader, was also a popular Democratic politician who had represented the Minnesota Territory in Congress and served as the state’s first governor when it received statehood in 1858.[6] On September 19, Sibley’s command advanced north from Ft. Ridgely towards Little Crow’s camp.

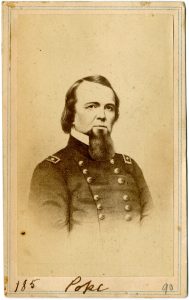

The decisive battle of the campaign came at Wood Lake on September 23, where Little Crow’s forces were defeated. After Sibley told them that he only wanted to punish the guilty, anti-war Dakota leaders seized control of the captives and offered to surrender, while Little Crow and his followers fled. Two days later, the remaining Dakota surrendered 91 “pure white women and children,” along with approximately 150 captives of mixed ancestry. On October 9, General John Pope, commander of the Department of the Northwest, reported to Washington that the “Sioux war may be considered at an end.”[8]

After securing the captives, Sibley reported to General Pope that he immediately “issued an order appointing a military commission, consisting of … Colonel [William] Crooks, Lieutenant-Colonel [William] Marshall, and Captain [Hiram] Grant, for the examination of all the men, half-breeds as well as Indians, in the camp near us, with instructions to sift the [background] of each, so that if there are guilty parties among them they can be arrested and properly dealt with.”[9] Rev. Stephen R. Riggs, who had been a missionary to the Dakota and accompanied Sibley’s force as chaplain, was also involved in investigating possible charges. There was a general assumption in Minnesota that almost all the captured women had been raped, and the commission members appear to have believed that female captives would be more comfortable discussing sexual mistreatment with a man of the cloth rather than a panel of militia officers. One of the captives, Sarah Wakefield, described the process as follows: “In the afternoon they had a sort of court of inquiry, and we [captives] were all questioned by Col. Crooks and [Lt. Col.] Marshal (sic), … [Rev.] S.R. Riggs and others. I was the first one questioned. I related to them briefly what [happened] …, after which, Col. Marshall said ‘If you have anything of a more private nature to relate, you can communicate it to Mr. Riggs.’ I did not understand until he explained himself more fully. I told them it was just as I related, it was all. They thought it very strange I had no complaints to make, but did not appear to believe me.”[10]

Lincoln did not refer the records to Judge Advocate General Holt for a legal review as was the usual practice for military death sentences. As fortune would have it, on November 27, 1862, Holt began prosecuting the court-martial of General Fitz John Porter, a task that would fully occupy him until the following January. While both Ruggles and Whiting were lawyers, they were merely asked to determine whether any of the defendants merited executive clemency, based on the President’s instructions, and not to determine the legality of the proceedings. However, the President’s instructions to them embodied an important legal principle. In effect, Lincoln decided to treat the Dakota warriors the same way Confederate soldiers were treated. If captured, the latter were not punished for treason or murdering Union soldiers in battle, but held as prisoners of war. Similarly, the Dakota who had merely participated in battles would be kept in custody, but not punished for combat against armed whites.

Lincoln did not refer the records to Judge Advocate General Holt for a legal review as was the usual practice for military death sentences. As fortune would have it, on November 27, 1862, Holt began prosecuting the court-martial of General Fitz John Porter, a task that would fully occupy him until the following January. While both Ruggles and Whiting were lawyers, they were merely asked to determine whether any of the defendants merited executive clemency, based on the President’s instructions, and not to determine the legality of the proceedings. However, the President’s instructions to them embodied an important legal principle. In effect, Lincoln decided to treat the Dakota warriors the same way Confederate soldiers were treated. If captured, the latter were not punished for treason or murdering Union soldiers in battle, but held as prisoners of war. Similarly, the Dakota who had merely participated in battles would be kept in custody, but not punished for combat against armed whites.

One may wonder why Ruggles and Whiting, two undistinguished mid-level bureaucrats, were selected to review the records. There is a suggestive precedent from earlier in 1862. On February 27, Secretary of War Stanton, “by order of the President,” appointed General John Dix and Edwards Pierrepont to examine the cases of all political prisoners being held without trial, “to determine whether in view of the public safety and the existing rebellion they should be discharged or remain in military custody.”

Dix was a Democrat and Pierrepont a Republican, thereby insulating the administration from charges that prisoners were released or held based on their political persuasion. Similarly, Ruggles was a Republican politician, a former Whig and Know-Nothing who played an important role in merging the New York Know-Nothings into the state Republican Party. Whiting was a Democrat, having been appointed to a patronage position by President Van Buren in 1838, and promoted to Commissioner of Pensions in 1857 by President Buchanan. He must have had anti-slavery credentials, since the Lincoln administration retained him to coordinate the prosecution of slave traders.

Again, the administration was insulated against accusations that it overturned 262 death sentences because Sibley was a Democrat, or that by this unpopular act Lincoln had failed to take the interests of the Minnesota Republican Party into account. Even after the hangings, President Lincoln continued to avoid the issue. In March 1863, on a visit to Washington, Governor Ramsey asked the President what he would do about the Dakota still in military custody. He replied that “it was a disagreeable subject but he would take it up and dispose of it.” He never did. He may have found the subject even more disagreeable a few days later, when a letter arrived from Sarah Wakefield, who reported that a Dakota man, who had saved her life and the lives of her children when they were captives, had been hanged by mistake, in place of a man with a similar name who had murdered a woman. For whatever reason, Lincoln could never bring himself to decide the fate of all the captive Dakota, and many were still in custody at his death. As predicted by some of their leaders, the Dakota eventually lost all their land in Minnesota and were moved to a barren reservation in the Dakota Territory.

On September 28, Colonel Sibley issued an order converting the military commission from an investigating body to a trial court. Two additional members were added, Captain Hiram Bailey and First Lieutenant Rollin Olin, and the commission was directed to “try summarily” those brought before it and “pass judgment upon them, if found guilty of murders or other outrages.” A local lawyer and volunteer militiaman, Isaac Heard, was detailed to record the trial proceedings, and the results were to be reported to Sibley for review. Finally, Sibley’s order instructed the commission members to “be governed in their proceedings by Military Law and usage.”[11] Unfortunately, none of the members knew very much about military law and usage. That included the senior member, or president, of the commission, Colonel Crooks. Although he had attended West Point (class of 1854), he left the Academy before graduating to pursue a career as a civil engineer.

The trials began on September 28 at Camp Release, the military post where the captives were first received. Initially the commission proceeded carefully. By October 4, twenty-nine trials had been held, but shortly thereafter Colonel Sibley made a decision that greatly expanded the commission’s case load. According to Isaac Heard, as a result of the “evidence before the commission indicating that the whole (Dakota) nation was involved in the war,” he ordered all the Dakota men who had surrendered to be disarmed, arrested and brought before the commission, which now had to deal with almost 400 defendants.[12] A standard form of charge was developed and reproduced, with a blank space for the name of the accused:

“In this that the said ___________,

Sioux Indian did join with and

participate in the murders, outrages

and robberies committed on the

Minnesota Frontier by the Sioux

Tribe of Indians between the 18th

day of August 1862 and the 28th day

of September 1862 and particularly

in the Battles at the Fort, Birch-

Coulie [sic], New Ulm and Wood

Lake.”

This form gave the accused no effective notice of the real charges against him. Moreover, under this charge a Dakota man could be convicted and sentenced to death for simply participating in battles against white soldiers, such as the two attacks on Ft. Ridgely or the final battle at Wood Lake. As Isaac Heard explained, all that was required for conviction was evidence, or an admission by the accused, “that he had fired in the battles, or brought ammunition, or acted as commissary in supplying provisions to the combatants.”[13]

By November 5, the commission had tried 397 persons and sentenced 307 to death. Sixteen, who had not participated in battles or raped or murdered civilians, were sentenced to prison for looting. The last 272 cases were tried in ten days. Sometimes forty cases were disposed of in one day, and death sentences imposed after trials lasting five minutes.[14]

By November 5, the commission had tried 397 persons and sentenced 307 to death. Sixteen, who had not participated in battles or raped or murdered civilians, were sentenced to prison for looting. The last 272 cases were tried in ten days. Sometimes forty cases were disposed of in one day, and death sentences imposed after trials lasting five minutes.[14]

Sibley, by now a Brigadier General, approved all but one of the death sentences. However, he had earlier told General Pope that he was “somewhat in doubt whether my authority extends quite so far” as to order the executions to be carried out,[15] and therefore requested guidance from Pope. Sibley’s doubts were justified. In the summer of 1862 Congress had passed an act providing that in courts-martial and military commission trials, “no sentence of death, or imprisonment in the penitentiary, shall be carried into execution until the same shall have been approved by the President.”[16] In the evening of November 7, General Pope telegraphed President Lincoln the names of 300 Dakota who had been condemned to hang. He began the telegram by informing the President that the, “following named Indians have been condemned to be hung by the military commission assembled at the Lower Sioux Agency for the masacre [sic] of men & women & Brutal violating of women & young Girls in the late Indian outrages in Minn.”[17] The lengthy telegram cost the U.S. government $414.04. The President read the telegram the next day and two days later directed Pope to, “forward as soon as possible the full and complete record of their convictions; and if the record does not fully indicate the more guilty and influential of the culprits, please have a careful statement made on these points and forwarded to me.”[18] Tweaking Pope for his long telegram, President Lincoln added, “Send all by mail.” The General, never known for his reticence, shot back the next day that “the only distinction between the culprits is as to which of them murdered most people or violated most young girls[;] all of them are guilty of these things in more or less degree.”[19] Pope’s certainty on this point is remarkable, since the records of trial did not arrive at his headquarters in St. Paul until several days later, on November 15.

Lincoln’s decision to review the Dakota trial records has taken on a certain mythic quality, stressing the time and care the busy President personally devoted to the 300 records of trial condemning to death members of a people despised by their white neighbors. For example, David Herbert Donald wrote that “… the President deliberately went through the record of each convicted man, seeking to identify those who had been guilty of the most atrocious crimes, especially murder of innocent farmers and rape.”[20] More recently, William Lee Miller described how Lincoln “personally – in the midst of Civil War pressures and woes – went through the records, one by one, of the convicted Sioux,” and “worked through the transcripts for a month.”[21] Unfortunately, the chronology does not allow for the extensive examination by the President described by Lincoln’s biographers.

According to Chaplain Riggs, he delivered the 300 records of trial to Pope’s headquarters on November 15. [22]The President reported to the Senate on December 11 that the records of trial were not received at the White House until “two or three days before the present meeting of Congress,” on December 1.[23] That would put the date of arrival at November 27 at the earliest. On November 26 and 27, Lincoln was visiting the Army of the Potomac to confer with its new commander, General Burnside,[24] so the earliest he would have seen the records was probably November 28. Lincoln’s telegram to General Sibley approving 39 executions was dated December 6, so at most Lincoln and his advisers had nine days to sift through 300 case files.

15. [22]The President reported to the Senate on December 11 that the records of trial were not received at the White House until “two or three days before the present meeting of Congress,” on December 1.[23] That would put the date of arrival at November 27 at the earliest. On November 26 and 27, Lincoln was visiting the Army of the Potomac to confer with its new commander, General Burnside,[24] so the earliest he would have seen the records was probably November 28. Lincoln’s telegram to General Sibley approving 39 executions was dated December 6, so at most Lincoln and his advisers had nine days to sift through 300 case files.

When he first glanced at the records of trial, the President was undoubtedly appalled. From years of legal practice before the Illinois courts, and his review of courts-martial and military commissions as president, he knew what a proper record of trial looked like. In contrast, the Minnesota records were a mess, hastily written on sheets of paper of different sizes and colors, even on half sheets torn in two. Some records had obvious defects, such as a failure to record that witnesses had been sworn in before testifying.

Having requested the trial records, the President found he did not have the time, or perhaps the desire, to deal with the messy and politically divisive issues they raised. Minnesota had been a solidly Republican state, but when it was revealed that the President was even considering clemency for the Dakota, there was massive public outrage.[25] Governor Ramsey wired the President that if Lincoln didn’t want to approve the hangings, Ramsey was willing to do it for him.[26] General Sibley, who had ordered the trials and approved the sentences, was a Democrat and a local hero for having rescued the captives. The Republicans had already suffered electoral losses in the fall of 1862, following the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Reviewing these records was the last thing the President needed as Congress reconvened and General Burnside prepared to attack Lee’s army at Fredericksburg. Lincoln asked his adviser on military law, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, whether he could delegate the task of approving the sentences to a subordinate; Holt replied that he could not.[27]

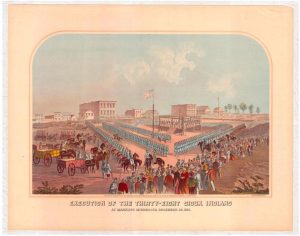

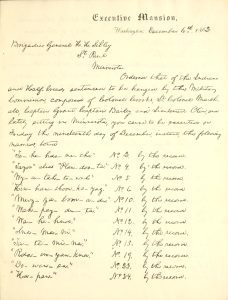

Two subordinate officials, Francis A. Ruggles of the State Department and George C. Whiting of the Interior Department, were called to the White House to examine the records and ascertain which defendants had committed rape and to determine “those who were proven to have participated in massacres as distinguished from participation in battles.”[28] Applying these criteria, Ruggles and Whiting reported back on December 5 a list of 40 names, two of whom had been convicted of both rape and murder, and the rest of murder. The next day, the President, having decided to accept the military commission’s recommendation to commute one prisoner’s death sentence to imprisonment, wrote a telegram to Sibley approving the execution of 39 Dakota. Another defendant later received executive clemency, and the remaining 38 were hanged at Mankato on December 26.[29]

Lincoln did not refer the records to Judge Advocate General Holt for a legal review as was the usual practice for military death sentences. As fortune would have it, on November 27, 1862, Holt began prosecuting the court-martial of General Fitz John Porter, a task that would fully occupy him until the following January.[30] While both Ruggles and Whiting were lawyers, they were merely asked to determine whether any of the defendants merited executive clemency, based on the President’s instructions, and not to determine the legality of the proceedings. However, the President’s instructions to them embodied an important legal principle. In effect, Lincoln decided to treat the Dakota warriors the same way Confederate soldiers were treated. If captured, the latter were not punished for treason or murdering Union soldiers in battle, but held as prisoners of war. Similarly, the Dakota who had merely participated in battles would be kept in custody, but not punished for combat against armed whites.

One may wonder why Ruggles and Whiting, two undistinguished mid-level bureaucrats, were selected to review the records. There is a suggestive precedent from earlier in 1862. On February 27, Secretary of War Stanton, “by order of the President,” appointed General John Dix and Edwards Pierrepont to examine the cases of all political prisoners being held without trial, “to determine whether in view of the public safety and the existing rebellion they should be discharged or remain in military custody.”[31] Dix was a Democrat and Pierrepont a Republican, thereby insulating the administration from charges that prisoners were released or held based on their political persuasion. Similarly, Ruggles was a Republican politician, a former Whig and Know-Nothing who played an important role in merging the New York Know-Nothings into the state Republican Party.[32] Whiting was a Democrat, having been appointed to a patronage position by President Van Buren in 1838, and promoted to Commissioner of Pensions in 1857 by President Buchanan. He must have had anti-slavery credentials, since the Lincoln administration retained him to coordinate the prosecution of slave traders.[33] Again, the administration was insulated against accusations that it overturned 262 death sentences because Sibley was a Democrat, or that by this unpopular act Lincoln had failed to take the interests of the Minnesota Republican Party into account.

Even after the hangings, President Lincoln continued to avoid the issue. In March 1863, on a visit to Washington, Governor Ramsey asked the President what he would do about the Dakota still in military custody. He replied that “it was a disagreeable subject but he would take it up and dispose of it.”[34] He never did. He may have found the subject even more disagreeable a few days later, when a letter arrived from Sarah Wakefield, who reported that a Dakota man, who had saved her life and the lives of her children when they were captives, had been hanged by mistake, in place of a man with a similar name who had murdered a woman. For whatever reason, Lincoln could never bring himself to decide the fate of all the captive Dakota, and many were still in custody at his death. As predicted by some of their leaders, the Dakota eventually lost all their land in Minnesota and were moved to a barren reservation in the Dakota Territory.

Burrus Carnahan is Adjunct Professor of Law at George Washington University in Washington, DC.

This article was originally published in the August 2012 issue of the Lincoln Cottage Newsletter.

[1] The people called themselves the Dakota, though they were commonly referred to as the Sioux by the U.S. government and American whites. The word “Sioux” is a contraction of a name coined by their traditional adversaries, the Chippewas, and means “enemy” in that language. Duane Schultz, Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862, p. 16 (St. Martins, 1992).

[2] For general accounts of the origins and conduct of the war, see Duane Schultz, supra; Kenneth Carley, The Dakota War of 1862 (2nd ed., Minn. Historical Society, 1976); and Isaac D. Heard, History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863 (Nabu facsimile reprint of 1863 ed.). Heard was a contemporary witness to events who served as a member of the Minnesota militia during the fighting and acted as official recorder of the military commission trials. Like many whites of his time, he regarded the Dakota as savages, but also believed that the U.S. government had treated them unjustly and deserved much of the blame for the outbreak of the war. Heard’s accounts of debates among the Dakota were based on interviews with the surviving Dakota participants.

[3] Isaac D. Heard, supra note 2, pp. 243, 248.

[4] Ramsey to Stanton, August 21, 1862, in The War of The Rebellion: A Compilation of The Official Records of The Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, vol. XIII, p. 590 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1885) (hereinafter Official Records).

[5] Wilkinson, Dole and Nicolay to the President, August 27, 1862, in Official Records, series 1, vol. XIII, p. 599.

[6] “Henry H. (Hastings) Sibley,” Minnesota Historical Society website, http://www.mnhs.org/people/governors/gov/gov_04.htm; Duane Schultz, supra note 2, pp. 88 – 92.

[7] Sibley to Pope, September 27, 1862, in Official Records series 1, vol. XIII, p. 679. More captives were freed as other Dakota bands who had retained their captives were either captured or surrendered, raising the number to 107 whites and 162 of mixed ancestry, for a total of 269 captives freed. Kenneth Carley, supra note 2, p. 65.

[8] Pope to Halleck, October 9, 1862, in Official Records, series 1, vol. XIII, p. 722.

[9] Sibley to Pope, September 27, 1862, supra.

[10] Sarah F. Wakefield, Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees, pp. 113-14 (June Namias ed., U. of Oklahoma Press, 1997; originally published in 1864).

[11] Order No. 55, Headquarters Camp Release, September 28, 1862. The order can be found at the beginning of each of the 39 records of trial submitted by President Lincoln to the Senate on December 11, 1862, Ex. Doc. No. 7, 37th Congress, Third Session, U.S, National Archives Record Group 46. Lt. Col. Marshall was later relieved to perform other military duties, and Major George Bradley named to replace him. Isaac Heard, supra note 2, p. 251.

[12]Isaac Heard, supra note 2, p. 188. See also Duane Schultz, supra note 1, pp. 245-47.

[13] Isaac Heard, supra note 2, p. 269.

[14] Id. pp. 254-55; Duane Schultz, supra note 1, p. 252; Kenneth Carley, supra note 2, p. 69.

[15] Sibley to Pope, September 28, 1862, in Official Records, series 1, vol. XIII, pp. 686-87.

[16] Act of July 17, 1862, chapter 201, section 5, 12 Stat. 597.

[17] Pope to Lincoln, November 7, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. It is not known why Pope did not include the other six defendants whose death sentences had been approved by General Sibley.

[18] Lincoln to Pope, November 10, 1862, in Official Records, series 1, vol. XIII, p. 787; The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. V, p. 493 (Roy Basler, ed., Rutgers U. Press, 1953) (hereinafter Collected Works).

[19] Pope to Lincoln, November 11, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[20] David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, p. 394 (1995). See also William Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 276 (1972 reprint of 1948 Knopf ed.): “Then the President studied the trial records and concluded that only thirty-nine of the prisoners had committed crimes deserving death.”

[21] William Lee Miller, President Lincoln: The Duty of a Statesman, pp.324-25 (Knopf, 2008).

[22] Riggs to Lincoln, November 17, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[23] Message of the President in Answer to a Resolution of the Senate o of the 5th Instant in Relation to the Indian Barbarities in Minnesota, December 11, 1862, Senate Ex.Doc. No.7, 37th Congress, Third Session. Lincoln’s message, without enclosures, appears in Collected Works, vol. V, pp. 550-51.

[24] Lincoln to Halleck, November 27, 1862, in Collected Works, vol. V, pp. 514-15.

[25] David A. Nichols, Lincoln and the Indians, p. 101-04 (U. of Missouri Press, 1978); Duane Schultz, supra note 1, pp. 254-58.

[26] Ramsey to Lincoln, November 28, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[27] Lincoln to Holt, December 1, 1862, in Collected Works, vol. V, pp. 537-38; Holt to Lincoln, December 1, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[28] Message of the President, supra note 24. Emphasis in original.

[29] Sibley to Lincoln, December 27, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[30]Joshua E. Kastenberg, Law in War, War as Law, pp. 86-89 (Carolina Academic Press, 2011).

[31] Executive Order No. 2, Relating to Political Prisoners, War Dept., Washington, February 27, 1862, in Official Records, series 2, vol. II, p. 249.

[32] For Ruggles’ background see Roy Franklin Nichols, “Some Problems of the First Republican Presidential Campaign,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 28, No. 3, April 1923, pp. 492-96; “Ruggles, Francis H,” http://www.ourcampaigns.com/CandidateDetail.html?CandidateID=169336.

[33] See summary of Whiting’s career in Papers of Andrew Johnson, 1858-1860, (Leroy P. Graf, Ralph W. Hastings eds. 1972) U. of Tenn. Press, vol. 3, p. 458 note; see also Records Of The Office Of The Secretary Of The Interior Relating To The Suppression Of The African Slave Trade And Negro Colonization, 1854-72, http://www.fold3.com/pdf/M160.pdf.

[34] Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 372 (Don Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher eds., Stanford U. Press, 1996).

[35] Wakefield to Lincoln, March 23, 1862, in the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.