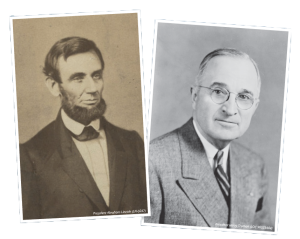

Lincoln & Truman: Varied Expressions of the American Spirit

Lincoln & Truman: Varied Expressions of the American Spirit

By Max J. Skidmore

There is, to be sure, an element of unfairness in a comparison of any other president with Abraham Lincoln. It’s a rare presidential ranking that fails to put Lincoln at the top of the list as America’s most outstanding president. Admittedly – although I have participated in many of them, and certainly they are interesting – the value of rankings is highly questionable.

First, is it reasonable to ask what could we learn from comparing chief executives who served in extremely varied circumstances? For example, consider comparing two quite able, very successful, popular, Republican presidents – such as, say, Eisenhower and McKinley – and concluding that one ranks so many points above the other. Can such a comparison tell us anything significant? These presidents were in office separated considerably in time, in expectations, in external conditions, in powers, and in visibility.

Second, nearly all rankings are developed from questionnaires that historians or political scientists who generally have some expertise regarding the presidency fill out. Yet it is unusual to find people in either field who have much knowledge of all the presidents. It is especially rare to find people who have in-depth knowledge of each of them. In any case, the questionnaires seeking information for ranking do not examine the qualifications of those asked to supply that information.

Moreover, now that there has been a flood of presidential rankings since the initial one that Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., pioneered in 1948, they have certainly influenced subsequent rankings. Nearly all who participate would be at least somewhat familiar with rankings and are likely as a result to go along with their predecessors in placing presidents about whom they know little.

Off the tops of their heads, how many of those contributing to rankings can honestly speak meaningfully about, for example, Millard Fillmore, Zachary Taylor, Chester Arthur, or Benjamin Harrison? Also to the point, how can anyone think it reasonable to rank James A. Garfield, who was effective only for about four months until an assassin shot him, causing him to die after a couple of tortured months later? From the viewpoint of rankings, isn’t it even more egregious (and unfair to him) to include William Henry Harrison, whose presidency lasted all of one month? Even if rankings in general have enough value to be taken seriously, how can anyone believe that it is fair to compare a president who was in office only a month with others who had far longer to make their mark?

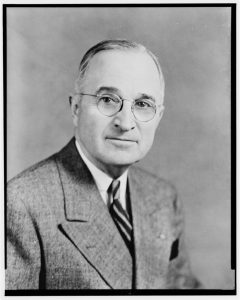

Having begun with such a criticism, I certainly concede that it would be the rare observer who could take issue with any placement of Lincoln at the top, with Washington and FDR following, or with Pierce, Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, or Trump far below the others. Truman’s reputation was at a low ebb when he left office, but has risen through the years to rank him as at least among the near-greats.

A comparison between Lincoln and Truman in this respect would point to consistency: Lincoln’s consistent position at the top, and Truman’s consistent rise, boosted by popular culture. Truman’s down-to-earth qualities wore well, and the partisan sniping that plagued him while in office dwindled afterward, while at the same time the public’s affection for him grew.

At the risk of reaching, I suspect each of these outstanding presidents, Lincoln and Truman, would be skeptical of rankings. It may be reaching even more, but I believe also that each, despite their widely varied circumstances and talents, would be appreciative of the other; certainly, each deserves appreciation. We do know that Truman thought highly of Lincoln. In Merle Miller’s remarkable oral history,[2] Truman numerous times praised Lincoln. Referring to Lincoln’s comment that it is possible to fool some of the people some of the time, Truman said, “Old Abe was right about that as he was about most other things.”[3] “If Lincoln said it, the chances are ninety-nine out of a hundred that I would agree with it..” [4] “Lincoln was a great president.”[5] Both presidents came from modest backgrounds; in Lincoln’s case, the poverty was severe.[6] He was born on the frontier, virtually in the wilderness, on February 12, 1809. He made his way by determination, intellect, and a sense of justice. He had, to put it mildly, a strained relationship with his harsh father who had either no understanding of, or possibly no concern for, his exceptional son. He was close to his mother, Nancy Hanks, from whom he believed he had received his mind. Tragically, she died when Lincoln was nine. Fortuitously, his father married again.

Lincoln’s stepmother was Sarah Bush Johnston, or “Sally.” She “soon loved Abraham as if he were her own son.” Lincoln, similarly, “adored” her, and she encouraged him to read everything he could find. Both she and Lincoln mentioned, years later, how determined he was to understand everything that adults were saying, and never to permit himself to rest without fully comprehending anything to which he was exposed.[7] That characteristic was, however subtly, to characterize him throughout his life.

There is less detail available about Truman’s boyhood, but he was born in Lamar, Missouri, a small village in a rural area. There is no information regarding his brief time in Lamar, and the family moved several times during the first few years of his life. The birthplace home, though, today is a historic site that the state of Missouri owns and maintains. The town of Lamar, after Truman’s birth on May 8, 1884, played no role in his life, nor did the small house in which he was born. As Robert Ferrell put it, Truman’s parents had built it for $685, moved away a year later and sold it for $1,600, and it then “passed from their minds. When Harry ran for U.S. senator in 1934 he returned; there is no evidence he had visited earlier. Nominated for the vice presidency in 1944, he chose Lamar for the notification ceremony, but until that year his wife and daughter had not seen the place.”[8]

His father was a small man with a fiery temper that frequently led him into fights, where he fought “like a buzzsaw.”[9] His volatility, fortunately, did not carry over into family life. Truman biographers generally agree that he never hit the children, and some even portray him as a caring father.[10] There seems certainly not to have been the animosity toward his father that characterized Lincoln’s upbringing, but Truman, like Lincoln, was closer to his mother.

In 1889, the family, having moved to a farm owned by his grandfather, Solomon Young, had gone out to view a Fourth of July fireworks display. It became apparent “that Harry Truman had a problem with his eyes.” He could not see the display in the sky, and only heard the explosions.[11] He was discovered to be extremely nearsighted, and a doctor fitted him with thick glasses. Glasses were to characterize him throughout the rest of his life. The doctor warned him not to engage in sports, and to avoid physical activities that might break them. That led him in his boyhood to be different. It could be described in many ways as out of the mainstream. He was never “one of the fighters as he called them.” He ran from fights, David McCullough said, and quotes him as saying that he endured teasing because of his glasses.[12] Certainly it was uncommon for children to wear them at the time. “To tell the truth,” Truman told Merle Miller in his oral history, “I was kind of a sissy.”[13]

His brother Vivian, though, remembered it differently. He said Harry was not teased. Rather than being a sissy, it was merely that he was different, serious. The other boys respected him, recognizing that he had read widely and possessed an immense store of useful information. They turned to him for information to settle disputes. If they were arguing the history of the James gang, for example, they would trust him to know the historical facts.[14]

Whatever the truth is regarding his fleeing violence as a child, such reticence did not carry over into adulthood. Numerous biographies describe how Truman volunteered for service in the Great War at the advanced age of 33 (when the draft called up men only through 32, and in any case exempted farmers as essential workers), and how he memorized the eye chart so that his poor vision would not disqualify him. He served with valor and extraordinary courage.

Moreover, the quality of his leadership was clear, as demonstrated by the outstanding performance of the unit he commanded as captain. He inspired loyalty as well. Men who served under him demonstrated their respect by supporting him throughout his political career. In a rather concise but admirably comprehensive chapter, McCullough describes Truman’s military service, absolutely including combat, as a turning point in his life. For someone who had never been in a fight, and who never before faced danger, it was an extraordinary awakening. Harry Truman’s natural qualities emerged, and he had become a leader.[15]

Biography also contributed to the resuscitation of Harry Truman’s reputation. As indicated, that reputation was very low when he left office in January 1953, but it proceeded to grow steadily on its own. Like Adams, Truman had the disadvantage of succeeding a giant figure, in his case Franklin D. Roosevelt; unlike Adams, Truman had a personality that wore well, and he fared far better than any other president who followed a truly extraordinary figure (Adams, Van Buren, Andrew Johnson, and Taft). Truman could be petty—and he was hardly charismatic—but he radiated honesty, had generally good judgment, was forthright, and was decisive. More and more the public came to appreciate his plain-spoken style. When he died (December 1972) the country was being shaken by Vietnam, had just delivered a crushing defeat to the Democrats, and may have been marginally aware that it soon would be shaken yet again by “Watergate” – the most serious presidential scandal in history until the Trump era submerged it under a cascade of unprecedented and completely unanticipated presidential actions.

In 1973 Alonzo Hamby published an analytical work on Truman’s presidency,[16] and soon, in 1975, so great had Truman’s stature become that “Give ‘Em Hell Harry,” a one-man show with James Whitmore playing Truman, had its debut in Washington, D.C.; it captivated the country. Whitmore received an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Truman in the same year the film version appeared. The stage show for years played regularly around the country, and finally made it to New York in 2008.

Other books praising Truman followed, as did television shows. Perhaps most successful in portraying the “Man from Missouri” to a general audience was the hugely popular—and also excellent—biography by David McCullough.[17] In 1992, when McCullough brought out that massive and publicly acclaimed biography, Truman, Truman’s reputation had shot into the ranking stratosphere.

As an aside, despite the excellence of McCullough’s histories, many academicians find it too painful to give due recognition to works that are accessible and popular. One historian I remember hearing on NPR sniffed that McCullough “received the ‘obligatory’ Pulitzer, of course.” The identity of that historian has faded from my memory, while memories of Truman, and yes, McCullough, remain strong.

Truman brought McCullough his first Pulitzer Prize, and solidified Truman’s reputation as an outstanding American president. Robert Ferrell then brought out an in-depth study in 1994,[18] and Alzono Hamby added yet another in 1995.[19]

Lincoln and Truman certainly were unlike physically. Lincoln was physically imposing; Truman was not. As a young man, Lincoln was celebrated as a wrestler who could defeat all comers. He had prodigious strength. Doris Kearns Goodwin relates the well-known incident that took place when Lincoln, who then was in his 50s, was on a Treasury ship steaming to meet with his reluctant (yet arrogant) general, George McClellan. “Lincoln playfully demonstrated that in ‘muscular power he was one in a thousand,’ possessing ‘the strength of a giant.’ He picked up an ax and ‘held it at arm’s length at the extremity of the [handle] with his thumb and forefinger, continuing to hold it there for a number of minutes. The most powerful sailors on board tried in vain to imitate him.”[20]

Both Truman and Lincoln had integrity and determination. Each was driven to do the right thing regardless of opposition or threats to reputation. An immediate difference, according to Miller, was that “Lincoln was an outwardly melancholy man. Truman was not. His general demeanor was sunny, and if he experienced depths of depression or despair, he kept it private.”[21] Lincoln had charisma, Truman had a down-to-earth appeal. Each had experienced racist conditions – in fact, each had grown up in a society in which racism was pervasive – yet each had risen above his surroundings and become outraged at the inevitable injustices that racism generated. As a young man Lincoln was exposed to slavery when he took a flatboat trip to the Deep South. He thought that he had to do something to reform the system if ever he were in a position to do so.

Both Truman and Lincoln had some racist sentiments when young, but each had an innate sense of fairness that prevented him from developing the virulent racism with which his society bombarded him. When President Truman was informed of the maiming of a veteran returning home from defending his country, he determined to use his presidential powers to do something about it.

Each also took an action that only a very few people in history could have had the power to accomplish. That is, each fired a popular general (in Lincoln’s case, two: Frémont, and McClellan). Lincoln, though, was the only president whose entire presidency was characterized by the overwhelming presence of war.

As to that civil war, unquestionably it was a huge tragedy, killing over 600,000 Americans; recent estimates have elevated that figure to 750,000 or so. In retrospect, many writers have concluded that such an enormous bloodbath could not have been justifiable. It is difficult, however, if not impossible, to come to that conclusion without a racist dismissal of the claims of millions of human beings to self-determination.

That is to say, Southern leaders were so determined to maintain their system of enslavement that it could never have been eradicated without force. As for a more moderate course, it is doubtful that it could ever have succeeded. Even if it could have been effective, such a course would have prolonged enslavement inexcusably. Just how much oppression could it ever be “justifiable” to ask of a people? It is worth noting here the observation of a subsequent president who was himself an accomplished historian, Theodore Roosevelt. “As regards the actual act of secession, the actual opening of the Civil War,” he said, “I think the right was exclusively with the Union people and the wrong exclusively with the secessionists.” He followed with, “I do not know of another struggle in history in which the sharp division between right and wrong can be made in such a clear-cut manner.” As I said when discussing this elsewhere, “Roosevelt’s mother was from the South and had sympathized with the Confederacy, and all his life he had taken pride in the heroic deeds of his maternal uncles who fought for the South. He was too keen an observer, however, to ignore the facts. Slavery and secession were indefensible.”[22]

As the conflict began, everyone knew what had happened. One has only to read the articles of secession that the Confederate states adopted to recognize the constant refrain of Southern complaint that the North was interfering, or was potentially interfering, with its “peculiar institution.” At the war’s end, there remained no doubt as to its cause: the South fought not only to retain but to expand its system of human chattel slavery.

By the end of the nineteenth century, though, it was obvious that fighting for the right to enslave people put the white South on the wrong side of history. Thus, a neo-Confederate school of historians arose to propagate the “Lost Cause” myth that dominated American history for decades. It obscured what should have been obvious: what the country almost assuredly would have become had Lincoln lost, had there been no Lincoln, or had there been no war. Historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (along with Harper’s Magazine’s Bernard DeVoto) was the exception who saw through the cant and recognized its implications.

Schlesinger spoke of an “amateur historian of impeccable Confederate ancestry” who made it clear that the Civil War had been justified. This historian was Harry Truman himself, who wrote a commentary on an article by MacKinlay Kantor in Look Magazine titled “If the South Had Won the Civil War.” Truman was sufficiently realistic to base his interpretation on the facts, rather than received “wisdom” of the Lost Cause. If Lee had won, he said:

“England would have recognized the Confederacy, and France would have stayed in Mexico with a French Empire from Panama to the Rio Grande. . . . Russia would have kept Alaska and in all probability have taken all Northwestern Canada.

There would have been the Northwest Republic, the Northeast Republic, the Confederate Republic, the Mexican Empire in the Southwest, with California, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico as part of that Empire.

And the Bolsheviks would have had the whole Northwest, and what then? Maybe the Northeast and the Southeast could have created an alliance and held the Russians at the Mississippi. Isn’t it great to contemplate?

My sympathies and my family were on the side of the South. But I think the organization of the greatest republic in the history of the world was worth all the sacrifices made to save it.”

Truman wrote this from retirement in Independence, Missouri. One thing he failed to mention is that the Confederate republic—assuming that it survived—would have maintained its practice of enslaving people, but because of Lincoln and the Civil War no longer was there an extensive system of human slavery in the Western Hemisphere.[23] What Lincoln accomplished required “superb political skills as well as steeled determination.”[24] The distinguished historian John Hope Franklin (who, of course, was far above the Lost Cause school), outlined Lincoln’s shrewd politics. Lincoln, he wrote, had been successful in arranging for Nevada, where Republicans were strong, to be admitted in time for its electoral votes to be counted. He issued orders for soldiers who wanted to go home to vote to be furloughed to do so, assuming correctly that they would be supportive. “He had been responsible for the disintegration of the opposition within the party and for undermining the arguments and proposals advanced by Democrats. The political victory of 1864 was therefore in a real sense a Lincoln victory.”[25]

Bruce Catton summed it up. He wrote, perceptively, “there have been few bitter-end fighters in all history quite as tenacious as Abraham Lincoln.”[26]

Being a “bitter-end fighter,” though, does not describe the complete Lincoln. He had a poetic sense as well. Although he provides no source, Epstein has said that “while no one nowadays wishes Lincoln had given up politics, the critics Jacques Barzun and Edmund Wilson have both proposed that Lincoln – alone among our presidents – could have made a lasting contribution to American letters if he had preferred a literary career.”[27]

In fairness, one should note that other presidents did write poetry. Despite his dour countenance, John Quincy Adams is among them, as is Jimmy Carter, whose 1994 Always a Reckoning and Other Poems received some favorable comment from critics.

Lincoln was certainly among America’s most cerebral presidents, but he had no formal education. His reading was characterized more by depth than by breadth, yet he was superbly—considering his challenges one might conclude uniquely—successful. Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson obviously possessed keen intelligence also—it is not too extreme to say that along with Lincoln they exhibited political genius—but they were not scholars nor were they “intellectuals.” Unlike Lincoln, they were not among our most “cerebral” presidents, yet Jackson and FDR performed skillfully in office, and LBJ was extraordinarily effective in his domestic policy.

Lincoln’s exposure to Transcendentalism came primarily from the works of three of its prominent adherents: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Theodore Parker. His law partner, William Herndon, called his attention to Parker’s writings.[28] As president, Lincoln’s mastery of the language enabled him to create in the Gettysburg Address what Garry Wills accurately described as “The Words that Remade America.” Wills pays tribute to his genius: “Lincoln was an artist.” His address “created a political prose for America, to rank with the vernacular excellence of Twain.”[29]

In his Gettysburg Address of a mere 272 words, Lincoln portrayed the Declaration of Independence as America’s founding document, with the Constitution as a splendid but necessarily imperfect instrument designed to approximate the Declaration’s ideal. “Equality” took its place among America’s fundamental principles. Lincoln’s “dialectic of ideals struggling for their realization in history owes a great deal to the primary intellectual fashion of his period, Transcendentalism.” The Declaration became an influence not limited to America; it was one that radiated “out to all people everywhere.”[31] As Hutchison put it, Lincoln had “transplanted” the “‘transcendentalist’ credo to the political sphere.”[32]

Wills quotes Hemingway that “all modern American novels are the offspring of Huckleberry Finn. It is no greater exaggeration.” Wills adds, “to say that all modern political prose descends from the Gettysburg Address.”[33] Lincoln “was a Transcendentalist without the fuzziness. He spoke a modern language because he was dealing with a scientific age. . . . Words were weapons, for him, even though he meant them to be weapons of peace in the midst of war.” Wills does not exaggerate when he writes that Lincoln “came to change the world, to effect an intellectual revolution. No other words could have done it. The miracle is that these words did. In his brief time before the crowd at Gettysburg he wove a spell that has not, yet, been broken. . . .”[34]

Wills wrote these words some three decades ago. Recently, that spell has become strained. America entered dark days: its government first engaged in pre-emptive war, and subsequently installed a president who seemed to believe that he could rule without limit – or at least that he should be able to do so, even disregarding the vote itself – thus coming close to erasing Lincoln’s “self-government.” Those days have not passed, despite the discrediting of the administration that brought them, but optimists see promise that they are ending.

Lincoln’s interpretation of the Declaration was the interpretation that most Americans had come to accept;[35] it may yet be restored as official policy, considering that we now have rational leadership in office. Repairing the damage, though, will take time, and will depend upon the continuation of rational leadership.

Wills notes that “preparing the public mind” was of great importance in an age of Transcendentalism.[36] It is no less important now that Lincoln’s principles have suffered erosion from such powerful assault. Using the proper words, adopting literature to the task may be of great assistance in the restoration. It will require wisdom and leadership of enormous skill. The world will join us in hoping that it will not require another Abraham Lincoln.

Another Truman might be sufficient. His thoughtful practicality, his informed common sense, may be enough to form an effective substitute for Lincoln’s Transcendentalism. Recent American politics may offer reason for hope. In September 2022, after President Biden’s culmination of policy successes (both legislative and by executive order) and his talks giving blunt defenses of democracy against any and all attackers, “pundits” began to say he had found his inner Truman.[37]

To be fair, considering the intensely partisan nature of today’s politics – partisanship that eclipses even the bitterness of Truman’s time – such comparisons of Biden with Truman usually have come from Democrats.

The first such comparison, though, came just after Biden’s inauguration. Director of the Truman Library and Museum, Kurt Graham, noted a number of similarities, including especially the humility of each.[38] So, there may now be a glimmer of hope. Considering the turmoil and irrationality of the political scene today, even a glimmer is welcome.

Max Skidmore is University of Missouri Curators’ Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus. This paper was presented at the 39th Annual Abraham Lincoln Lecture at Louisiana State University Shreveport on October 22, 2022.

[1] On Garfield, see the superb and in-depth study by Candice Millard, Destiny of the Republic, New York: Doubleday, 2011.

[2] Merle Miller, Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman, New York: Berkeley Publishing/Putnam’s, 1973.

[3] Ibid, p. 143.

[4] Ibid. p. 156.

[5] Ibid. p. 407

[6] See Richard Striner, Summoned to Glory: The Audacious Life of Abraham Lincoln, Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020, chapter 1, “Rough Beginnings”; for a brief, but superb, treatment of Lincoln’s early life.

[7] Ibid., pp, 6-7.

[8] Robert H. Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: A Life, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994, pp. 7-8; note: the website for the State Historical Site indicates that Truman’s parents “bought” the house¾this may be inconsistent, or it may be imprecise wording; Ferrell does not give a citation. See https://mostateparks.com/page/54969/general-information (retrieved Sept 6, 2022)

[9] David McCullough, Truman, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992, p. 47.

[10] See, e.g., Ferrell, pp.4-5.

[11] Ibid., p. 10.

[12] McCullough, p. 45

[13] Merle Miller, Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman, New York: Berkeley, 1974, p. 32.

[14] McCullough, p. 45.

[15] McCullough, Chapter 4.

[16] Alonzo Hamby, Beyond the New Deal: Harry S. Truman and American Liberalism, New York: Columbia University Press, 1973.

[17] David McCullough, Truman, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

[18] Robert H. Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: A Life, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994.

[19] Hamby, Man of the People, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

[20] Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln,” New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005, pp. 436-437.

[21] Miller, p. 29.

[22] See Max J. Skidmore, Presidential Performance, Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004, p. 129, for the quotation and the discussion.

[23] All material here is from Skidmore, Presidential Performance, p. 133; the Schlesinger reference, and the Truman quotation, are reprinted in Presidential Performance from Schlesinger, A Life in the 20th Century, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 2000, p 452.

[24] Skidmore, ibid.

[25] John Hope Franklin, “Lincoln and the Politics of War,” in Ralph G. Newman, ed., Lincoln for the Ages, New York: Pyramid Books, 1960, p. 81.

[26] Bruce Catton, This Hallowed Ground, New York: Washingon Square Books, 1956, pp. 429-430.

[27] Daniel Mark Epstein, Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington,” New York: Ballantine Books, 2004, p. 19.

[28] Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992, p. 106.

[29] Ibid., p, 52.

[30] For a different interpretation, see Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006.

[31] Wills, p. 103

[32] Anthony Hutchison, Writing the Republic, New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 52

[33] Wills., p. 148.

[34] Ibid., pp. 174-175.

[35] Ibid., p. 147.

[36] Ibid., p. 120.

[37] For an example (this one from a conservative), see Gary J. Schmitt, “”Biden’s Truman Moment,” The Dispatch (American Enterprise Institute) (February 21, 2022), https://www.aei.org/op-eds/bidens-truman-moment/ ; retrieved October 7, 2022).

[38] Carey Wickersham, “Truman Presidential Library Sees Comparison Between President Biden, Truman,” Fox 4 Morning News, Kansas City (Jan. 23, 2021); https://fox4kc.com/news/truman-presidential-library-sees-comparison-between-president-biden-truman/ retrieved September 27, 2022.