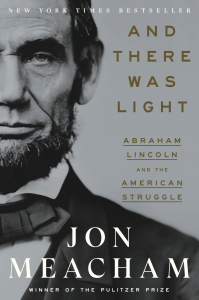

Book Review: Jon Meacham, And There Was Light

Jon Meacham, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle

Book Review by Phelps Gay

Not just another cradle-to-grave biography setting forth well-known facts of Lincoln’s life, And There Was Light offers us a fresh look at his intellectual, moral, and spiritual development culminating in his decision to resist the voices of compromise and bring an end to American slavery. Over a brisk 421 pages, Jon Meacham weaves together a compelling narrative firmly grounded in—though not weighed down by—meticulous research. From the first sentence of the prologue to the last of the epilogue, we are in the hands of a skillful storyteller who knows how to elucidate and entertain. The result is a book Lincoln aficionados will not want to miss.

For those who believe Lincoln did not seriously engage with anti-slavery ideas until Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, Meacham offers a corrective. Married by an antislavery clergyman named Jesse Head, Lincoln’s parents became “steeped full of Jesse Head’s notions about the wrong of slavery and the rights of man as explained by Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine.” In Kentucky, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln belonged to an emancipation group called the Baptist Licking-Locust Association Friends of Humanity, which declared that “every enlightened citizen abhors slavery . . . as a sin against God.”

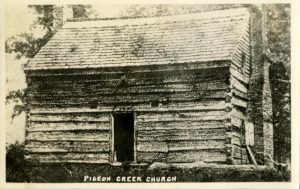

In Indiana, Abraham served as sexton in the Little Pigeon Creek Baptist Church. As we know, after services Lincoln would go out to work in the field, get up on a stump, and repeat verbatim a sermon he had just heard. But Meacham dives deeper, telling us these sermons were preached by two antislavery ministers, William Downs and David Elkin, offering vivid profiles of each. He also traces “the roots of religious antislavery convictions” on both sides of the Atlantic, from the work of Rev. John Newton (who wrote “Amazing Grace”) to the teachings of Methodist John Wesley to the preaching of David Barrow, a Baptist minister who helped found the Licking-Locust Association in Kentucky.

Thus, later in life, when Lincoln described himself as “naturally antislavery,” Meacham notes “he was not manufacturing a useful past for political purposes. He was reporting the fact of the matter.”

At the same time, something in Lincoln’s questing mind resisted strict adherence to religious orthodoxy, particularly the Baptist notion of predestination. Meacham ends his chapter on Lincoln’s religious upbringing with a remark Lincoln reportedly made as a young man: “Probably it is to be my lot to go on in a twilight, feeling and reasoning my way through life, as questioning, doubting Thomas did.” Question and doubt he did, becoming “voraciously curious” during his New Salem years. He was particularly influenced by Constantin Volney’s The Ruins, or, Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires and Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason because of “their insistence on the individual interpretation of reality rather than the blind acceptance of tradition.” As Paine put it, “My mind is my own church.” Under this spell Lincoln prepared “an extended essay” against Christianity, contending Jesus Christ was not the son of God. According to his law partner and biographer, William Herndon, this essay was “read and freely discussed” in New Salem circles.

Enter Samuel Hill, a friend of Lincoln’s who “snatched the manuscript and thrust it into the stove.” As Herndon recalled, “the book went up in flames and Lincoln’s political future was secure.” In recent remarks at the annual symposium of The Lincoln Forum, Meacham observed: “If not for Samuel Hill, we wouldn’t be here.”

According to Lincoln’s friend Jesse Fell, “no religious views with him seemed to find any favor except of the practical and rationalistic order,” but, he added, if “called upon to designate an author whose views most nearly represented Lincoln’s on this subject, I would say the author was Theodore Parker.”

A major theme of this book is that conscience is divinely inspired. Over time Lincoln’s struggle to find “the right thing to do” became bound up with his effort to discern the will of God. Meacham tells the story of Parker’s inclination as a boy to “poke a little spotted tortoise sunning himself in the shallow water” of a stream, when he heard a voice say: “It is wrong!” He asked his mother: “What just happened?” His mother replied, “Some men call it conscience, but I prefer to call it the voice of God in the soul of man. If you listen and obey it, then it will speak clearer and clearer, and always guide you right, but if you turn a deaf ear and disobey it will fade out little by little and leave you all in the dark without a guide.”

For the reform Unitarian minister and abolitionist Parker (as for Lincoln) the Bible was not “the end of the conversation, but the beginning.” To ground a claim about reality “solely on scripture absent reason and conscience” was, for Parker, “risible and wrong.” God gave us mind and conscience, both of which were to be “engaged in guiding the lives of individuals and of nations.” Principles of justice and good were “of divine origin,” and “people could discern those principles through reason and interpret them through conscience.”

Meacham provides Parker’s precise words regarding the “arc of the moral universe,” words later shortened by Martin Luther King, Jr., and Barack Obama. In an 1853 sermon called “Of Justice and the Conscience,” he said:

“I do not pretend to understand the moral universe, the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. But from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

In the 1850s Parker corresponded with William Herndon, and a sermon Parker delivered in Boston to the New England Anti-Slavery Convention resonated with Lincoln. Extolling the “American idea” that all men are created equal and have inalienable rights, Parker said that “government is to be established and sustained for the purpose of giving every man an opportunity for the enjoyment and development of all these inalienable rights.” Foreshadowing a certain address later delivered by Lincoln, Parker said this idea “demands…a democracy, that is, a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people; of course, a government after the principles of eternal justice, the unchanging law of God.”

What Meacham charts in this book is Lincoln’s progression from a young skeptic to an “art-of-the-possible” politician to a president determined to discern and follow the will of God. Tempered by tragic experience—including the unspeakable death and suffering caused by the Civil War and the death of his son Willie—Lincoln embraced the idea of a living God who acts in human history. In his “Meditation on the Divine Will” he wrote, “In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party.” Visiting with Chicago ministers in September of 1862 (pre-Antietam), he assured them he was considering whether to issue an emancipation proclamation with these words: “Whatever shall appear to be God’s will, I will do.”

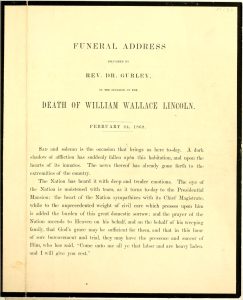

Here I would add that Meacham also portrays Lincoln’s relationship with Rev. Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, as significant in his spiritual development during the Civil War years. As an “articulate proponent of a doctrine of Divine Providence that held the world was charged with theological import, even if the purposes of the Almighty remained mysterious,” Gurley offered Lincoln “a worldview that acknowledged the invisible while simultaneously investing humankind with the responsibility of bringing the visible and the tangible into closer accord with an ideal of justice.”

After Willie’s death, Gurley counseled: “God’s ways are not our ways.” “What we need in the hour of trial,” he said, “is confidence in Him who sees the end from the beginning . . . let us hear His voice and inquire after His will.” Meacham hastens to add that Lincoln’s experience with Gurley “did not amount to a conversion”; instead, it was an “immersion in a Presbyterian theology in which God was an active participant in the affairs of the world.”

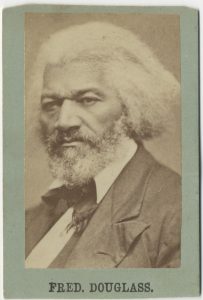

In the Second Inaugural, which to Frederick Douglass “sounded more like a sermon than a state paper,” Lincoln emphasized that while North and South “pray to the same God,” the “prayers of both could not be answered,” and “neither has been answered fully.” Instead Lincoln suggested that “the Almighty has his own purposes,” and that as punishment for the “offense” of American Slavery a “Living God” gave to both North and South “the woe due to those by whom the offense came.” Writing to Thurlow Weed eleven days later, Lincoln observed that “men are not flattered by being shown there is a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, is to deny that there is a God governing the world.”

For this reader And There Was Light shines brightest when the author focuses on Lincoln’s intellectual and spiritual development. An Episcopalian currently serving as Canon Historian at the Washington National Cathedral, Meacham is deeply knowledgeable about religious history and takes care to explain the source and meaning of all Biblical references, whether made by Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Theodore Parker, or others. At the same time, he is a gifted journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, so that the story of Lincoln’s life flows forward in crisp, graceful prose spiced with erudition and wit.

In fairness, those looking for a full factual account of Lincoln’s life might look elsewhere. There is little here regarding Civil War battles, not very much on the Lincoln marriage or law practice, and no reference to his near-duel with James Shields or the Lincoln-Berry store, aside from a glancing reference to its “winking out.” For such thoroughness one must turn to Michael Burlingame’s indispensable two-volume Abraham Lincoln: A Life. On the other hand, Meacham does an excellent job within the space allotted (or chosen), working in acute observations and pithy quotes from a wide variety of sources, all of which are scrupulously documented in 153 pages of source notes. Such concision gives the book a certain momentum and allows it to stay focused on its theme.

In tracing the course of Lincoln’s moral development, Meacham is careful not to characterize him as a saint or martyr. As shown in his remarks at Charleston, Illinois, during the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln was not above pandering to racial prejudice in his quest for political advancement, and he was slower than contemporaries like Charles Sumner and Salmon Chase to suggest equal rights for African Americans such as voting and jury service. Still, Meacham convincingly demonstrates that at critical junctures—such as resisting the proposed Crittenden Compromise in 1861; adhering to emancipation as a precondition of peace in August 1864, despite the prospect of defeat in the upcoming presidential election; and pressing forward with House passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in January 1865—Lincoln stood fast, guided by conscience.

Hovering over these pages is the stentorian voice of Frederick Douglass, who alternately criticized and praised Lincoln’s actions as president, not always appreciating that a wise political leader must sometimes move slowly to get great things done. Looking back in 1876, Douglass registered his appreciation for what Lincoln had accomplished: “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground,” he said, “Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

Throughout, Meacham’s writing is polished—indeed, often dramatically “novelistic,” as in this first sentence: “The Storm had come from the South.” Vivid and sometimes surprising details crop up, such as Lincoln’s high regard for English politician and reformer John Bright, whose portrait (one of only two) Lincoln hung in his White House office, and a near-cinematic account of Frederick Douglass’s persistent and ultimately successful attempt to get past security to congratulate Lincoln on his Second Inaugural. Mining all possible sources—letters, diaries, speeches, newspaper accounts, and “recollected words”—Meacham condenses them into a highly readable narrative. Much like his subject, he enjoys telling stories, and he does it well.

The book is also handsomely put together, with well-chosen epigraphs, color portraits of persons mentioned in the text, and drawings of places Lincoln lived, wrapped in a stylish dust jacket. In this age of PowerPoint, where one is expected not just to tell but show, Meacham and his editors have met all expectations.

In sum, from his perch as a public intellectual and popular historian, one whose image we often see on television and whose books routinely shoot to the top of the bestseller list, Jon Meacham doesn’t merely recount Lincoln’s well-known story. Through lively prose, fresh analysis, and painstaking research, he enriches our understanding of Lincoln’s intellectual and spiritual journey. As Harold Holzer has observed, this book “instantly takes its place at the forefront of Lincoln literature.”