Lincoln & Poetry

Lincoln & Poetry

Lincoln & Poetry

Sara Gabbard

In any scholarly biography of Abraham Lincoln, a reader will find countless references to this prairie lawyer’s love of poetry. I’m not sure that biographers will ever come up with a definitive explanation for this passion. Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon told the story that, once when they were on horseback riding to an event, Lincoln mentioned that he was puzzled about the genesis of his love for learning… given the fact that his parents were illiterate pioneers. His only explanation was that he thought that there was a possibility that his mother, Nancy Hanks, was illegitimate…and that her father was an educated Virginia planter.

We only have Herndon’s description of this conversation, and, as far as we know, Lincoln did not mention the subject again…to anyone. I don’t know that this family influence could hold true, even if the facts were basically correct. After all, the more direct influence on the future president would have come from his parents and the family and friends with whom he spent his formative years.

We can be certain, however, that something burned deep down inside the young frontiersman. We know about the borrowed books; the attempts to learn to write on wooden objects with charcoal; and the “stump speeches” with which he regaled his friends by repeating word-for-word sermons given by itinerant preachers.

We know from many reliable reports that, when riding the 8th Judicial Circuit in Central Illinois, in the evenings, lawyers would often huddle around a fireplace and listen to this tall, gangly resident of Springfield tell stories and quote poetry. And when you think of lawyers all riding together and staying in the “quaint” country inns of the prairie, you need to know that the phrase I used about huddling around the fireplace was not simply to paint a homey picture. They had to huddle around the fire because the inns were dark, dreary, and drafty.

While the future president is better known for quoting poetry, there are a couple of poems which he wrote.

These two items are from his Copy Book, probably written between 1824 and 1826:

Abraham Lincoln

his hand and pen

he will be good but

god knows whenAbraham Lincoln is my nam(e)

And with my pen I wrote the same

I wrote in both haste and speed

And left it here for fools to read

In 1844, Abraham Lincoln journeyed from Illinois back to Southern Indiana. He wrote a lengthy poem about the experience and titled it: My Childhood Home I See Again

My childhood home I see again,

And gladden with the view;

And still, as mem’ries crowd my brain,

There’s sadness in it too.O memory! Thou mid-way world

‘Twixt Earth and Paradise,

Where things decayed, and loved ones lost

In dreamy shadows rise.Now twenty years have passed away,

Since here I bid farewell

To woods, and fields, and scenes of play

And school mates loved so well.

Where many were, how few remain

Of old familiar things!But seeing these to mind again

The lost and absent brings.The friends I left that parting dayHow changed, as time has sped!

Young childhood grown, strong manhood grey,

And half of all are dead.I hear the lone survivors tell

How nought from death could save,

Till every sound appears a knell,

And every spot a grave.I range the fields with a pensive tread,

And pace the hollow rooms;

And feel (companions of the dead)

I’m living in the tombs.The very spot where grew the bread

That formed my bones, I see.

How strange, old field, on thee to tread,

And feel I’m part of thee.

There are many stanzas which describe the awful reality of madness, but the poem ends in a stanza which, while Abraham never wanted to spend his life as a subsistence farmer like his father, shows a certain affection for the land itself. When asked to contribute material for a campaign biography in 1860, Lincoln said that his life’s story was best illustrated by a line from Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”…The short and simple Annals of the Poor. The full stanza for that sentence reads:

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor

Lincoln read, remembered, quoted, and loved Shakespeare. Both on the judicial circuit and later in Washington, people commented that he frequently quoted from Richard II:

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings:

How some have been depos’d, some slain in war

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping kill’d

All murdered.

Charles Sumner reported that on a steamer bound for Washington, on the last Sunday of his life, Lincoln read aloud from Hamlet, in retrospect a passage which appears to be prophetic:

Duncan is in his grave

After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well;

Treason has done his worst; nor steel nor poison

Malice domestic, foreign levy, nothing

Can touch him further

Lincoln called Shakespeare and Robert Burns “my two favorite authors, and I must manage to see their birthplaces some day if I can contrive to cross the Atlantic.” He always carried a collection of Burns’ poems, and yet when asked to provide a toast for a celebration of the poet’s life at the Burns Club in Washington, Lincoln was unable to attend because of the war effort. He did not even send a noteworthy message. Instead, he replied: I can not frame a toast to Burns. I can say nothing of his generous heart, and transcendent genius.

poems, and yet when asked to provide a toast for a celebration of the poet’s life at the Burns Club in Washington, Lincoln was unable to attend because of the war effort. He did not even send a noteworthy message. Instead, he replied: I can not frame a toast to Burns. I can say nothing of his generous heart, and transcendent genius.

Abraham Lincoln’s favorite poem, which he frequently quoted from memory, was “Mortality” by William Knox. It is not a joyful poem, but it is typical of the era. Lincoln once commented that he would give everything he had if he could have “written as fine a piece as I think this is.”

O why should the spirit of mortal be proud!

Like a swift flitting meteor, a fast flying cloud,

A flash of the lightning, a break in the wave—

He passes from life to his rest in the grave.The leaves of the oak and the willows shall fade,

Be scattered around, and together be laid;

And the young and the old, and the low and the high,

Shall molder to dust, and together shall lie.

The poet attempts to show death as the ultimate leveler:

The hand of the king that the scepter hath borne,

The brow of the priest that the miter hath worn,

The eye of the sage, and the heart of the brave,

Are hidden and lost in the depths of the grave.The peasant whose lot was to sow and to reap,

The herdsman who climbed with his goats to the steep,

The beggar that wandered in search of his bread,

Have faded away like the grass that we tread.The saint that enjoyed the communion of Heaven,

The sinner that dared to remain unforgiven,

The wise and the foolish, the guilty and just,

Have quietly mingled their bones in the dust.

Knox goes on at length to explain that each generation is the same in that they “repeat every tale” and “see the same sights” as their fathers. The end of the poem is equally morbid:

And the smile and the tear, and the song and the dirge,

Still follow each other like surge upon surge.Tis the twink of an eye, ‘tis the draught of a breath,

From the blossom of health to the paleness of death,

From the gilded saloon to the bier and the shroud –

O why should the spirit of mortal be proud!

Whenever historians are asked to rate the impact of presidential inauguration speeches, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural on March 4, 1865, leads almost every poll. It has several references to the Bible, and in portions it reads more like poetry than prose. In at least one place it reads exactly like poetry:

Fondly do we hope

fervently do we pray

that this mighty scourge of war

may speedily pass away.

My own thought is that in the final paragraph of his Second Inaugural, Abraham Lincoln comes as close to combining prose and poetry as anyone before or since:

“With malice toward none; with charity

for all; with firmness in the right, as God

gives us to see the right, let us strive on to

finish the work we are in; to bind up the

nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall

have borne the battle, and for his widow

and his orphan — to do all which may

achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting

peace, among ourselves, and with all

nations.”

Lincoln’s assassination brought some of the most familiar American poems of all time. First, I want to mention two tributes which you might not know. The first short poem is by Samuel F. Smith, who also wrote “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”:

A Nation proudly keeps his deathless fame;

Let vale and rock, and hill and land, and sea

His memory swell – the anthem of the free.

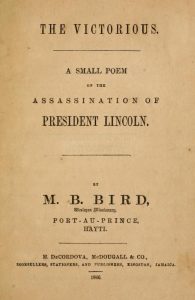

I’m fairly certain that you are not familiar with a small book which is carefully preserved at Allen County Public Library. “The Victorious” is a poem by M. B. Bird, a Wesleyan missionary to Haiti, is very fragile. This state of disrepair is explained by a note “Genuine Copies of this Brochure are Water Stained due to a Shipwreck.” Published in Jamaica in 1866, it is a great example of the melodramatic movements of the time: flowery speech; Biblical references; dark images (many references to fiends and Hell); and marvelous majestic moments (The mighty LINCOLN rose) Bird first addresses the evils of slavery, which he refers to as:

A frightful concentration of all Hell

On earth…

He then offers a powerful lamentation on the damage done to Africa and its inhabitants by the slave trade and its greedy perpetrators. Note the reference to Africa as the Continent of Ham, a derogatory referral to the sins of the son of Noah:

And, as at last the torch of history

I held, I saw the horrid monster stretch

Himself o’er all the Continent of Ham

I saw the fiendish monster spring his swarming

Fangs, and by one single effort, thousands

Wrench’d and tore away, from Fathers, Mothers,

Wives, all that on earth to them was dear. Shrieks

Rose to Heav’n, till a whole continent, with

Howling rang, and floated in a mingl’d

Sea of tears and blood.

The poem continues in this vein until the poet finally introduces Abraham Lincoln (the name always written in capital letters). Bird even comments on the name Abraham itself and refers to the martyred president as “our modern Moses”:

Hence, onward comes the mighty spir’t

Of the age; he nears, and now the monster’s

Final rage; arm’d with unbounded courage

Through a heaving sea of woe, he wades.

A giant soul, of lofty bearing, and

Strung up with the truth, majestically simple

In his air, he thinks, as in the presence

Of his God…Truth was to him a Sun which lighted all his soul

From whence, with Sun-bright clearness all within

Him saw, that foul idolatry of wrong

Must cease; yea, that a nation’s eye, at once

Must be pluckt out, and all the reas’ning of

Past ages must now be struck mute. To pause,

Or hesitate when Heav’n speaks, is crime;

Nor time is now for pause, the nation bleeds.

Truth her own throne must seize;

Whoever dares her Heav’n-born power, must sink.

Hence to the height of his great task,

The mighty LINCOLN rose, and broke the fetters

Of our modern days…

He then refers to the Civil War as a volcano which spewed forth “burning bolts of pride, hate, bloody tyr’nny, and death.” The nation was saved by Abraham Lincoln and the guidance of God, whose fame will be forever remembered:

Immortal LINCOLN! The whole earth at thy

Great name already thrills, the voice of Heav’n

In thee is heard, nor dost thou even thy

Own will perform. A higher will than thine,

Thy reason rules, yet nought in thee suspends.

Ages beyond us, shall with joy upon

Thy font, read with delight

“The sent of God.”

Abraham Lincoln will always be with us, and his death simply ensures that posterity will continue to honor him because “by the blood of LINCOLN, Heav’n bids the earth be free! The Master but recall’d his servant to Himself. LINCOLN then lives, his soul commands.”

Abraham Lincoln will always be with us, and his death simply ensures that posterity will continue to honor him because “by the blood of LINCOLN, Heav’n bids the earth be free! The Master but recall’d his servant to Himself. LINCOLN then lives, his soul commands.”

Perhaps the most memorable of all tributes to the assassinated president is Walt Whitman’s glorious poem, “Oh Captain! My Captain!” The poet refers to the Civil War as a long and dangerous voyage for the ship of state, with Abraham Lincoln serving as captain… and then the awful irony of Lincoln’s death just as the seas calmed and the future seemed so bright. The first stanza of the poem is almost shattering in its impact.

O Captain! My Captain!

Our fearful trip is done;

The ship has weather’d every rack,

the prize we sought is won;

The port is near, the bells I hear,

the people all exalting,

While follow eyes the steady keel,

the vessel grim and daring;

But O Heart! Heart! Heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

There are many aspects of Abraham Lincoln’s life which can be debated: Could the Civil War have been avoided? Did his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus set a questionable precedent? Whereas his selection of Cabinet members was, for the most part, outstanding, why did he continue to choose inept military commanders? Could he have been more sensitive to the obvious psychological problems of his wife? If he had lived, could he have healed the tragic wounds of both North and South during Reconstruction? In spite of those reasonable questions, one thing remains clear and without contradiction, his love for and use of poetry. Even much of his prose rang with the cadence of poetry.

It frequently allowed him to take joy in much loved poems, even during the constant and devastating news from the battlefield. It both strengthened and calmed him, and it is one of the main reasons that his mastery of language continues to place him at the top of our rankings of presidential eloquence.

Sara Gabbard is executive director of Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana and editor of Lincoln Lore.