History as Portrayed in Art: An Interview with Harold Holzer

History as Portrayed in Art: An Interview with Harold Holzer

History as Portrayed in Art: An Interview with Harold Holzer

Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Please explain the circumstances under which you and your co-authors (Gabor Boritt and Mark Neely, Jr.) undertook this enormous project.

Harold Holzer: Back in 1982—it’s hard to believe it was 40 years ago!—the three of us began discussing Lincoln engravings and lithographs as friends and colleagues. I’m not sure anyone else at the time was interested. Mark and Gabor may have heard me lecture on the subject at a Lincoln conference, one of the first occasions iconography had been taken seriously in the world of Lincoln scholarship. I had been writing articles on the subject for the Lincoln Herald and other publications, and I think I may have told my colleagues I had started working on a book.

Mark ventured the idea that it could coincide with an exhibition at the old Lincoln Museum; Gabor said he had a friend at Scribner’s who might be able to take on the project. In those days, I was a print collector, and had unearthed a few important pieces; Mark had a museum full of visual material that I had seen reproduced for years in Lincoln Lore (but not yet viewed for myself); and Gabor was interested in the economics of the subject—how these images were marketed and sold. He also had a built-in audience of Civil War enthusiasts at his home base, Gettysburg College. So we just decided to join forces—at a meeting in a Gettysburg hotel room, if I remember correctly. After that, we were just unstoppable: we committed to work both separately and in tandem on research, writing, and exhibit planning, even if we couldn’t be in the same room again for months at a stretch. And this was before email, home computers, and online research!

We even came up with a wonderful title: “Of the People, By the People, For the People: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print.” Thankfully, it was rejected by our editor, who one day simply told us the book would be called The Lincoln Image.

SG: How did you manage the project? Assignment of specific topics to one of you? Complete participation of all in everything?

HH: Four decades ago, we made a pact that we would never reveal which of us wrote which chapters. It was not just that we did not want to get hung up on who was doing more, or less, than the others. The idea was to cohere on our arguments, and to make sure each of us at some point handled every paragraph of writing—by drafting a section or editing it or adding to it. We would each take on separate assignments and do preliminary drafts, then we would work on each other’s work, separately and together, until stylistic differences faded, and it became hard to tell who had composed what (maybe except to us). We did such a good job I don’t think I can even recall how we first divvied things up. I thought it was a perfect partnership.

First of all, Mark and the Lincoln Museum had something neither Gabor nor I could lay our hands on: an actual word-processing computer and an assistant who could use it! Her name was (hopefully still is) Jewel Foster, and the advantage was that we could make handwritten corrections on a typescript, mail the pages to Fort Wayne, and have them flawlessly inserted into an updated draft without retyping from scratch…it was mind-boggling. People have asked me if we ever locked ourselves in a room to do editing and rewriting. We actually did so on several occasions—for exhausting marathons in both Fort Wayne and Gettysburg. But we also spent hours on conference calls, going over drafts page by page, sentence by sentence, literally for hours at a stretch. I can’t even imagine the bills we racked up. But the system worked. Meanwhile, both Gabor and Mark reserved museum spaces for the forthcoming exhibit, so we also began planning a traveling show of original art, and commenced to writing wall texts and labels even as we were finishing the book. I guess we were young! And our various institutions either supported or tolerated us. Gettysburg College got behind the project for Gabor Boritt; Ian Rolland was very enthusiastic from Lincoln Life; and my boss at WNET/Channel 13, John Jay Iselin, was in his heart a print man (he had been editor of Newsweek), so he cheered the idea that I was working on a book (as long as it wasn’t on the company clock). By the time it came out, I was working for New York Governor Mario Cuomo, and Mario, I soon discovered, was an avid and learned Lincoln admirer in his own right. But that’s another story.

SG: Did you have a specific goal in mind, e.g. balance between early life and presidency?

HH: At the outset, the goal was simply to write the first comprehensive study of Lincoln image-making: how it was done, why, by whom, and to what effect? Our structure built on the outline I’d prepared for my original book idea, and it broke down about one-third pre-presidential, one-third presidential, and one-third the pictorial memorialization immediately after the assassination. I think we basically adhered to that arrangement. I was always most interested in how engravings and lithographs introduced presidential candidate Lincoln to the country; I’d say Mark was more focused on the presidency, including emancipation, and all of us had ideas about the memorialization. But we never imposed boundaries on our individual research or writing.

Mark found some wonderful archival material on print-selling in 1860, Gabor had great ideas about Lincoln’s image as commander-in-chief, and I dug deeper into some of the areas I had covered for magazines and journals: Lincoln’s image transformation (whiskers), and Lincoln family depictions, and what they were designed to convey. Of course we also parsed the pictures in our various collections. I like to think I brought a starting point to the work because I knew the oeuvre best. But we just added layer upon layer of research, interpretation, analysis, and data that shed light on the audience, the industry, and the artists. And it just became fun looking for, even measuring the dimensions, of prints. I still cherish the experience. One of the best professional times of my career.

SG: In The Lincoln Image the statement was made: “As political image-shapers, printed pictures complemented the printed word. Historians of the Lincoln era have long studied the words. It is time to study the pictures, too.” Why did it take so long to recognize the importance of images?

HH: I don’t think historians meant to disrespect or downgrade the visuals. They simply had limited access to them. After all, books routinely get deposited in libraries and schools, remain accessible to researchers, and survive the passage of time (and this was before Google Books). But prints were originally produced and purchased as home decorations by Lincoln admirers (and in the case of anti-Lincoln images, by detractors). When they went out of fashion, their owners’ descendants tended to remove them from walls and at best store them in attics. Many pictures were simply tossed away.

That’s one reason why Mark, Gabor, and I wanted to be sure to include not only the most popular surviving images—the ones produced in such quantity that hundreds of examples had survived—but also the rare ones that may have missed the mark when they first appeared, or had been issued by regional publishers in smaller editions. I will add that we did think many historians had missed an opportunity. If they thought about these images at all, scholars long tended to treat them only as potential illustrations for their books—seldom bothering to identify the artists who’d created them, not to mention the circumstances that inspired their production. I like to think we planted these pictures into the scholarly consciousness. I don’t know whether or not we were responsible for stimulating further work on the subject, but there have been a good number of studies since, and scholars are still doing fresh and sophisticated analyses of Lincoln images.

I think the historical community has finally accepted the fact that pictures, not words alone, helped introduce Lincoln, vivify the Emancipation Proclamation, and elevate Lincoln into the realm of secular sainthood. At least we advanced the argument that these pictures didn’t just illustrate the evolving Lincoln reputation; they influenced it. As for any conflict of interest I brought to the table as a print collector, I soon found myself hoisted by my own petard. I remember visiting a New England flea market in the late 80s, finding a Lincoln print I’d long coveted, and being told it was astronomically expensive. “After all,” the dealer boasted, “it’s in The Lincoln Image.”

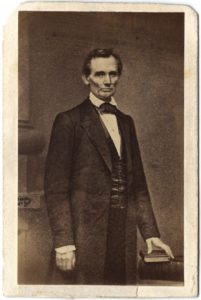

SG: Regarding the famous Brady photo of Lincoln taken on February 27, 1860, how did Lincoln and Brady first connect?

SG: Regarding the famous Brady photo of Lincoln taken on February 27, 1860, how did Lincoln and Brady first connect?

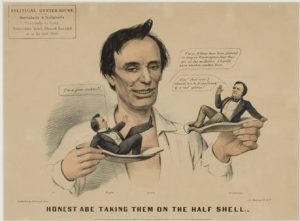

HH: Let me say first that while most Lincoln students think of the Brady image as an important example of early portrait photography (and rightly so), we strove to emphasize its importance as a model for engravings and lithographs. That’s because it enjoyed limited distribution in 1860 but stimulated dozens of reproductions for separate-sheet portraits, campaign banners, cartoons, and newspaper woodcuts. Think of the 1860 Currier & Ives cartoon (in the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection), Honest Abe Taking them on the Half Shell, which so brilliantly implied Lincoln was a giant among his rival candidates; it was based on that same Brady photo. And the Brady source was handsome enough to inspire flattering portraits that helped dispel rumors that Lincoln was too homely and ill-kempt to go to the White House.

As for how photographer and subject met, Lincoln’s February 1860 New York hosts simply walked him to Brady’s Manhattan gallery the day of his scheduled Cooper Union speech and asked their guest to pose for the city’s most prominent photographer. It was as simple as that. Brady was accustomed to making likenesses of visiting celebrities and publishing the results for profit (usually by selling rights to the picture weeklies). Did both men realize that this picture was special? Well, meeting for a second time in Washington a year later, then-President Elect Lincoln is said to have remarked that Brady’s picture helped elect him. By then, Lincoln well understood the power of images to work in his political, and ultimately his historical, behalf.

It might be mentioned that in 1860, Brady’s eyesight was already so impaired that he could no longer focus a camera. But he was still adept at posing his subjects, and when he decided to portray Lincoln from a bit of a distance, standing alongside a pillar and a stack of books symbolizing power and learning, respectively, he created a masterpiece. Lastly, he asked Lincoln to tug up his shirt collar. “I see you want to shorten my neck,” Lincoln self-consciously joked. Yes, Brady said, that was exactly what he had in mind—and the result made Lincoln look like a true statesman. Just keep in mind that the initial impact of the pose came through adaptations by the printmakers.

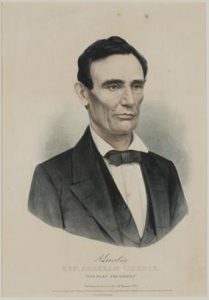

SG: What role did Currier & Ives play in documenting Lincoln and his era? Please explain the caption in the image titled “Our Next President.”

HH: New York’s leading lithographers played a huge role, though I think it had been largely misunderstood until we set the record straight in The Lincoln Image. For generations, people thought of the printmakers as Republican loyalists who enthusiastically produced Lincoln images to promote his presidential candidacies. This they did, of course, but not because they were Republicans, nor because they had been hired by the campaigns the way image consultants get retained today. Indeed, they simultaneously issued pro-Douglas images in 1860, and pro-McClellan portraits in 1864—not to mention deprecatory anti-Lincoln caricatures during both contests.

Currier & Ives weren’t partisans; they were businessmen, and they always sought the widest possible audiences for their pictures, never focusing on one side at the exclusion of the other. That said, Currier & Ives were hands down the most prolific, well-marketed picture operation in the country. They sold lithographs from their New York headquarters, through retailers around the country, in bulk to political organizations, and by mail via catalogue. They produced so many pictures so often that they could keep their prices down, guaranteeing the widest possible appeal. From 1860 through 1865, they published campaign images, prints that showed Lincoln with his new whiskers, pictures portraying the (exaggerated) impact of the Emancipation Proclamation, and truly newsworthy scenes of Lincoln’s murder and dying moments. Remember, at the same time the firm was churning out prints of kittens, pretty women, ice-skaters, racehorses, floral displays, and a host of genre subjects, not to mention an ambitious, if generic, series of Civil War battle scenes created for the parents, spouses, and sweethearts of the participants and casualties. Currier & Ives have been called the printmakers to the American People, a title they unquestionably deserve. But they should not be remembered as partisan publicists for Abraham Lincoln.

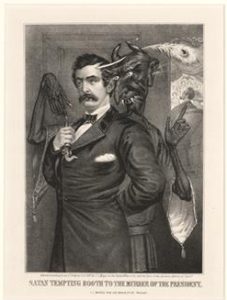

SG: Is “Satan Tempting Booth in the Murder of the President” typical of post-assassination images?

HH: In fact, it was a pretty unusual—and kind of crazy—interpretation. Keep in mind that by May 1865,

Currier & Ives had all but flooded the market with timely, if straightforward, murder, deathbed, and memorial prints of Lincoln. This meant that rival image-makers seeking their own audiences needed to devise new approaches. On the deathbed side of things, some commissioned artists (like Francis B. Carpenter) to make elaborate paintings of Lincoln breathing his last in unrealistic, palace-sized death chambers, but these took time to produce.

John Magee, a prolific but rather undistinguished New York lithographer, came up with the novel idea of portraying the Lincoln assassination from John Wilkes Booth’s perspective, and added the slimy image of Satan whispering murderous instructions into the actor’s ear. We see Lincoln only in the background, watching the play at Ford’s Theatre, unaware of the fate awaiting him. It’s an inventive, dramatic idea, even if the symbolism is absurdly heavy-handed, and the print is somewhat redeemed by a very good portrayal of Booth. But is it supposed to absolve Booth of responsibility for murdering Lincoln—because the devil made him do it? Most of Magee’s competitors, and the Library has many examples in its great collection, preferred to show the murder from the perspective of the theater audience—looking toward the presidential box as Booth fires his pistol. This image was truly an outlier.

SG: Is “In Memory of Abraham Lincoln – The Reward of the Just” fairly representative of images during the Romantic Era?

HH: It’s representative—and much more. It exudes not only romanticism but commercialism. This has always been one of my favorite Lincoln images. For years, I displayed my own cherished copy at home, and, I must say, the oversized picture of Lincoln in a nightgown floating into the clouds with a band of angels was always a good conversation-starter. In one way, D. T. Wiest’s picture is but one of a handful of “apotheosis” prints (and carte-de-visite photographs of those prints) published in the aftermath of the assassination to deify the martyred president. They all showed Lincoln ascending into an imagined afterlife, welcomed there in some versions by George Washington in a kind of celestial reunion of the founder and savior of the Union. What set Wiest’s print apart was its audacity.

The image was originally a George Washington apotheosis scene, first issued back in 1801. Hence it abounds with anomalies like a symbolic, weeping Native American (a liberated enslaved person would have been more apt for a Lincoln apotheosis), not to mention the Masonic symbol that decorates the opened tomb (Washington was a Freemason, Lincoln decidedly not). But it’s a bravura composition, so beautifully hand-colored, and so rich in detail (no other print shows Lincoln consorting with Faith, Hope, Charity, and Father Time). We included it in our 1984 exhibition, and it was an audience favorite. I miss having it in the house! I might say that we based our interpretation of the picture on some pioneering work in Lincoln iconography—by Milton Kaplan, among others, who first identified a number of prints showing Lincoln’s head on the bodies of politicians from the recent past.

We found a few unnoticed examples on our own. This gives me the chance to acknowledge other historians whose studies inspired us, including R. Gerald McMurtry, Mark’s predecessor at the Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne.

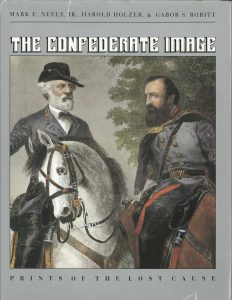

SG: I would ask the same question about The Confederate Image as I did of The Lincoln Image, what were the circumstances under which you, Gabor Boritt, and Mark Neely decided to embark on this project? Did you basically follow the same “research path” as with the Lincoln book?

HH: Well, we realized we had the potential for a James Bond-like series. Maybe that’s wishful reminiscing, but readers and publishers did seem to want more, and we enjoyed collaborating so much we were ready to go at it again. Actually, the first sequel we produced was a small book called Changing the Lincoln Image, published by the Lincoln Museum, and featuring some of the discoveries that had come our way after publishing the original book. Most of the new material was of the “darn, if only we’d known this” variety, and perhaps the publication was more an outlet for us than a must-read for Lincoln Image fans. Yet I’m still sorry that when the University of Illinois Press republished The Lincoln Image, it didn’t include Changing as a kind of epilogue.

I’m very proud of that little work. Anyway, we gravitated to the seemingly indestructible Lost Cause phenomenon, and we wondered if it had stimulated the kind of outpouring of images that Lincoln had. As we quickly discovered, such was the case—although it focused not on one sainted leader but a trinity: Davis, Lee, and Jackson. For this project, our research path proved different. The Lincoln Museum didn’t hold many Confederate or Lost Cause images, and Gettysburg was not exactly a hotbed of Rebel sentiment. So we went directly to the source, visiting repositories throughout the South. We conducted research forays to the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore and the Confederate Museum in Richmond, with side trips to New Orleans and of course, the lengthiest stop of all: The Library of Congress in Washington.

Once again, we divided up the writing work, and met in New York, Fort Wayne, Gettysburg and on the phone to hone the text. Once we understood the genre, we believed we had a great story, or rather two stories: the desperate effort in the Confederacy to keep its inspirational print industry alive amidst growing deprivation, and the enthusiastic, if unconscionable, effort by post-war Northern printmakers to sanctify Confederate heroes for commercial profit.

SG: When was the phrase “Lost Cause” first used? Does it mean the same thing today?

HH: I’d give credit, if that’s the right word, to a wartime Richmond journalist named Edward A. Pollard, who in 1866 published a book called The Lost Cause, billed a “new” account of the war, but from a decidedly southern and white supremacist perspective. This was just a year after Appomattox. Pollard knew he had unleashed something powerful. Just three years later he published a sequel entitled The Lost Cause Regained.

Indeed, Lost Cause memory has held a firm grip on many aspects of Southern culture ever since, still manifested in surviving public monuments and, one might say, intractable restrictions on voter rights. Our book also acknowledged Jefferson Davis’ role in stimulating a second wave of Confederate nostalgia when, as an old man in 1887, he made a triumphant trip to Montgomery, Alabama, the first Confederate capital, telling a huge throng of die-hard rebels: “Is it a lost cause now? Never…Truth crushed to earth will rise again.” By then, I’d say that the phrase meant what it came to mean for the next century and into our own time: a stubborn clinging to a myth-encrusted, whites-only interpretation of Civil War history in which state rights remained sacred, and the battle between North and South had been a clash of civilizations, not a war about slavery. Lee’s army had lost only when overwhelmed by superior forces, and slaves were grateful, though free black people could never be recognized as equal citizens. I think the three of us were fairly prescient when we described it in 1987 as “radical nostalgia.”

SG: Was there a difference between what Northern and Southern artists attempted to convey?

HH: In some ways, no—they both meant to glorify Confederate heroes; that’s where the money was for both—except that postwar Northern artists had more ink, paper, time, and talent. The earlier prints made in the Confederacy meant principally to portray newsworthy leaders and events—prints of Davis as a “First President” comparable to George Washington, along with the first images of Robert E. Lee—beardless and with a black moustache.

There were fewer lampoons in the wartime South (save for those directed at Lincoln) because, in the absence of a two-party system, the only product that sold was patriotic. Such morale-boosting tributes might have continued throughout the war—imagine the impact of, say, an 1862 image celebrating Lee’s triumph at Fredericksburg—except that by then, supply shortages had choked off print production in most Confederate cities, and countless artists had been conscripted for the military.

Two Southern cities where print production might have remained viable, Baltimore and New Orleans, had been seized early by Union forces, which promptly shut down production of Confederate images. But after the war, as Mark, Gabor and I came to realize, printmakers in New York, Boston, and Chicago stepped up to supply icon-hungry Southerners with the portraits they had lacked for so long. I’m rather proud that we identified the shameless commercialism—maybe bordering on disloyalty—which these publishers exhibited in the post-war years as they competed for a Southern marketplace closed off to them during the rebellion.

Business will always be business, and these image-makers expressed zero moral or political compunctions about filling the void. Much has been written in recent years about Lee statues being taken down or reappraised in Virginia. Lest we forget, the Lee engraving published as a premium to fund the recumbent Lee statue in Lexington was made not in the Confederacy but in New York City.

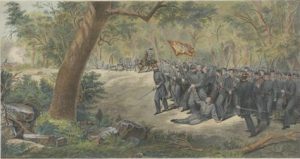

SG: A Currier & Ives print seems to romanticize “The Surrender of Gen Joe Johnson.” What are the details surrounding this image?

HH: Currier & Ives always got there firstest with the mostest, and surrender scenes became a particular specialty for the firm in 1865. First, they rushed out a scene of Lee’s earlier surrender to Grant at Appomattox. And while such prints elevated Grant’s image by depicting him as Lee’s equal, they also humanized Lee, and likely helped spare him the vengeance he may have deserved. Joe Johnston’s surrender (actually he surrendered twice) to William T. Sherman at the Bennett House near Greensboro, North Carolina, was something of an anti-climax, and one moreover to which Currier & Ives had no descriptions or depictions on which to base their lithograph. So they resorted to artistic clichés like aides-de-camp on horseback, and armies milling in the background, exaggerating a small, indoor ceremony into a panorama.

The image was certainly romanticized—how else to stimulate sales of a print of a non-newsworthy event?—but it certainly did not make the mistake of placing Sherman and Johnston on an equal footing. Sherman positively glares at his defeated opponent, arms folded, head covered, while Johnston meekly doffs his hat and holds his downturned sword un-threateningly at his side.

SG: I have heard you express the opinion that Abraham Lincoln understood the effect that photography and art could have on the war effort. Did Jefferson Davis have a similar understanding?

HH: I do think Lincoln came to comprehend the impact that the mass-distribution of photography and art impacted not only wartime Union morale, but also his own political fortunes and, ultimately, his historical standing. How else to explain his apparent eagerness to sit so frequently for Washington photographers, or to pose for artists as well as sculptors in the White House? Lincoln once called himself a “very indifferent judge” of the results, but he was also a very willing subject. Posing relaxed him, but that’s not enough of an explanation to justify all the time he devoted to visiting artists like Francis Carpenter, William Marshall Swayne, Edward D. Marchant, and Vinnie Ream.

As for Davis, I think he also harbored a basic understanding of the power of portraiture, but was handicapped by the much smaller means of image-distribution in the Confederacy. He did sit for a few photographs and paintings during the Civil War, but they enjoyed nothing like the widespread attention generated by Lincoln’s experiences with artists and photographers. I would add that both presidents recognized the power of portraiture before they took office. Lincoln posed for photographers and artists in Illinois starting right after his nomination in 1860. And, as Lincoln may have discovered when he glimpsed the wall of celebrity photographs that adorned Brady’s waiting room when he visited the gallery in 1860, Jefferson Davis had posed for a Brady photograph even before Lincoln did.

SG: Please explain “The Charge of the First Maryland Regiment.”

HH: This print is a real rarity, and it portrays a rather obscure moment involving a less-than-popular Confederate regiment. Yet it tells a great story about how and why certain Lost Cause prints got commissioned and distributed. It certainly vivifies a scene that might otherwise have been lost to history, namely the charge by a Maryland Confederate regiment (the so-called “Maryland Line”) at Harrisonburg, Virginia, on June 6, 1862. Those who forged both Confederate policy and Confederate memory had little use for Maryland volunteers, often eyeing them with suspicion because they hailed from a state that remained in the Union. But in 1867, the regiment’s commander, General Bradley T. Johnson, paid to have soldier-artist William Ludwell Sheppard’s painting of the charge copied in lithograph by a Baltimore printmaker who had been shuttered during the war: August Hoen.

Johnson then purchased and gave “a copy to every man who was there, or his son.” No wonder the benefactor later carped that his own portrait in the background was “very small & vague.” Instead, the image focused on a wounded color-bearer passing the flag to a comrade. Johnson’s personally financed distribution efforts, enhanced by the fact that proceeds were earmarked for a Baltimore monument to the Maryland Line, undoubtedly built sales. In such ways, Confederate reputations were recovered in popular prints. It would be interesting to find out how the Lincoln Collection’s copy came into its possession. We never unearthed the answer to that question. Sales records for 19th-century prints are exceedingly rare—even Currier & Ives’s files have never been found. That’s why analysis of these works often start and end with the pictures themselves, supplemented, when available, by surviving advertisements and reviews—and in the case of this particular print, a letter from an unreconstructed Confederate general with deep pockets.

SG: What role did cartoonists play in your story? Was the role different in the North than in the South?

HH: Cartoonists played a huge role in Civil War printmaking, and assumed a commensurate place in our “image” books. An entire chapter in The Confederate Image focused on cartoons that depicted Jeff Davis disguised in women’s clothes to escape Union pursuers after Appomattox. One of Currier & Ives’s most gifted artists, Louis Maurer, created caricature as well as portraiture, and both sides of his output—and his firm’s—elicited evaluation in the earlier book.

Our trio chose to focus almost exclusively on “separate sheet” lampoons published as display pieces, but we never quite solved the mystery of precisely how they got displayed. We did find some evidence that political organizations purchased copies in bulk. Did they end up on the walls of campaign headquarters, or tossed from windows at rallies?

On one occasion, an English visitor saw Lincoln cartoons on view in a Manhattan shop window; another observer remembered glimpsing a cartoon at a parade. Otherwise we still have very few clues about how these most transitory of popular prints were shown. It remains one of the frustratingly unanswered questions from all our years of research. Still, we always treated these comic pictures seriously: among them are timely, imaginative, and witty (sometimes racist) commentaries on the hot political questions of the day. They constitute an important part of the political and pictorial culture of the 19th century—a vessel for pent-up prejudices and boisterous humor—even if we haven’t quite figured out whose walls they adorned, and how it came to be that such quickly outdated ephemera survived.

SG: Given the controversy today that surrounds the depiction of history through art, would you have made any changes in the two books mentioned? Is statuary in a different category than prints, photography, etc.?

HH: I gave this inevitable question a great deal of thought, because I knew it would come up. To begin with, we always strove in our books to comment on 19th-century politics non-judgmentally, at least without applying 20th-century perceptions. Our goal was to focus on period art and commerce to recover the original impact and meaning of influential graphics, not to argue whether that influence was good or evil or even misplaced. Nonetheless, seizing the opportunity you handed me, I re-read the two books cover-to-cover for the first time in many years.

I must say, I ended up greatly relieved that there’s little there to embarrass the authors—at least in my judgment. Would I approach the subjects differently today? Would I alter or enhance a chapter here and there? Of course: these books were written in the 1980s, and if we haven’t learned a thing or two since then, we don’t deserve to be called historians, or even informed citizens. If I were re-writing the “Great Emancipator” chapter for The Lincoln Image, for example, I would include Reading the Emancipation Proclamation, a print that Mark and I did not publish until The Union Image in 2000: a scene showing a group of white soldiers reading the Proclamation to a black family—with Lincoln’s portrait relegated to the margins. Some excellent work has since been done on it by historian Aston Gonzalez.

Overall, I think the 1984 book holds up pretty well. It avoids hagiography and meets its original goal: to illuminate the image-makers’ role in the transfiguration of Lincoln from backwoods politician to national demigod. Whatever Lincoln’s standing today, there is no doubt the book accurately describes his evolving reputation from 1860 to 1865. And frankly if there was no way to do such a book today without pausing every five pages to remind readers that Lincoln was by modern standards a racist, then I’d rather not do the book at all. (I would find some way to say so once.) Of course, The Confederate Image is a bit more fraught. Would a book subtitled Prints of the Lost Cause even get published in the 2020s? Probably not. And perhaps, armed with hindsight and scissors, I would cut some of the more sentimental passages in the chapters that describe the Lost Cause phenomenon.

Our second Lee chapter bore the title “That Grand Man Loved by All,” and while it conveyed the fact that he was adored in the South, we could more clearly have said it was only the white South that venerated him. There is something that wouldn’t pass muster in the 2020s, and that’s a good thing. But The Confederate Image was also meant as an iconographic history, and I’m proud we explained the nostalgic impulse without ever coming close to embracing it. And If the book stands as a cautionary tale about dangerous over-simplistic deification, then it still serves a very good purpose.

Finally, I think that statues and public memorials are in a totally different category. They were made to preside over public space and inspire, or intimidate, on a mass scale. People purchased prints to adorn private spaces, to testify to their beliefs inside their own homes. So they are an invaluable tool for understanding American memory. I support removing objectionable statues. Prints have vanished from walls “on their own,” but I would fight to make sure that they are archivally preserved so that we can continue to study them.

Harold Holzer is the Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College.