Lincoln & Eisenhower: A Comparison

Lincoln & Eisenhower: A Comparison

By Richard Striner

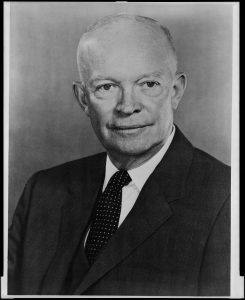

Abraham Lincoln and Dwight D. Eisenhower were strangely alike in some respects—kindred spirits. I have often wondered about the nature of this interesting correspondence in my research about presidents. I have been working on Lincoln more or less continuously since I wrote my book Father Abraham twenty years ago. My new Lincoln biography Summoned to Glory: The Audacious Life of Abraham Lincoln was published in 2020. I have just completed a biography of Eisenhower that will be published in 2023, titled Ike in Love and War: How Dwight D. Eisenhower Sacrificed Himself to Keep the Peace. These studies have led me to reflect at great length about these two presidents.

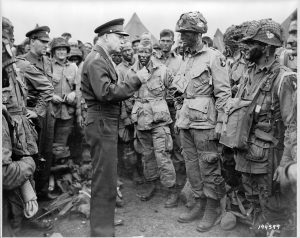

In certain ways, Lincoln and Eisenhower were extraordinarily different: they were great, but in different ways. Lincoln’s meteoric rise accompanied his charismatic words and deeds: his House Divided speech, his Cooper Union speech, and then his presidential words (and deeds) like the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address, and his eloquent Second Inaugural Address. With Ike, it was different. He could also be charismatic, and he was the greatest American hero of World War II. His role as D-Day commander made him a presidential contender, and his heroic reputation carried him into the White House. But Eisenhower was not known for the kind of oracular speeches that Lincoln gave, and even the best of his speeches—like his address at London’s medieval Guildhall after Germany surrendered—fell short of the grandeur that Lincoln attained at his best.

While Ike remained vastly popular as president, his governing style was so low-key that for years detractors were able to pillory him as an out-of-touch duffer who snoozed in the White House and wasted time on the golf course. The ironic truth was that Ike was a masterful president who deliberately kept his intentions hidden. He practiced what political scientist Fred Greenstein would later call the “hidden-hand presidency.” Ike’s presence in American memory has dwindled while Lincoln has remained iconic. It is only in the past generation that historians have started to grasp the full dimensions of what Eisenhower achieved.

But there were great commonalities between Lincoln and Eisenhower. And their personalities and lives make for interesting comparisons. They possessed very similar minds — they were “kindred spirits” despite their differences. Their innate gifts and distinctive patterns of development led to similar objectives and methods. Both possessed architectonic minds that could see the big picture in a flash and relate any part of a problem to the whole. Both were leaders who summoned overwhelming military force — practitioners of total war. Both were masters of deception who were guided by altruistic motives. Both strove to guard free society from the greatest threats that their generations confronted. And they both pursued their objectives through a combination of forthright advocacy and nuanced indirection when political realities dictated incremental methods. Both came from humble origins, and they were never close to their fathers. They had troubled love lives. Their personalities blended charismatic extroversion — with a penchant for mischievous humor — and a profound introversion that drove them to conceal their thoughts and intentions. They were both Republicans and they exemplified what Ike called the “Middle Way”: ideological synthesis. But they should never be regarded as “moderates”; they were much too bold for that label. They were dynamic centrists — visionary leaders who sought to shape the emerging future in a decisive manner.

They confronted the fundamental threats to the United States — slavery and disunion in Lincoln’s case, and the menace of the Axis powers followed by the threat of nuclear annihilation in the case of Eisenhower — and they forged new alignments of power that were designed to safeguard the nation and its values for a long time. As war leaders, they summoned overpowering force, and they orchestrated the actions of multiple forces to stretch the enemy thin. Such was the “broad front” campaign of Ike after D-Day. And such was the overall Union campaign of 1864 — so often attributed to the conceptions of Grant, but in truth a method that Lincoln had been trying to force upon his generals since 1862. Lincoln and Eisenhower sought to advance new conceptions in warfare, and they supported the development of advanced new weapons systems. They also sought to advance the cause of racial justice, and they did it through measured degrees. Their behind-the-scenes maneuvers were so carefully hidden that many years would elapse before scholars would be able to tease out the brilliant strategic ploys that they used to attain their objectives.

Eisenhower venerated Lincoln. Journalist Evan Thomas has written that while Grant and Lee were Ike’s foremost military heroes, “his greatest hero was Abraham Lincoln, the ‘master of men’ of Ike’s favorite biography, by Alonzo Rothschild. In his first year in the White House, Eisenhower had reread the story of how the Civil War president, by guile and patience, had bent to his will some outsized figures. In the small office at the back of Ike’s farmhouse at Gettysburg where he went to take secure telephone calls, there was but one picture, a portrait of Lincoln. In the glassed-in porch, on top of the TV set, sat a small bust of Lincoln.” Rothschild’s biography—Lincoln, Master of Men—was published in 1906.

The revolution in Lincoln scholarship that revealed the Machiavellian genius of Lincoln was well under way in Ike’s presidential years and it continued in the years leading up to his death: T. Harry Williams’ book Lincoln and His Generals appeared in 1952, Don Fehrenbacher’s study Prelude to Greatness was published in 1962, and Richard Current’s superb monograph Lincoln and the First Shot hit the shelves in 1963. But the flood tide of this revolution in Lincoln scholarship began after Eisenhower passed away in 1969. LaWanda Cox’s extraordinarily revealing exposé Lincoln and Black Freedom: A Study in Presidential Leadership was published in 1981. By a pleasant coincidence, Fred Greenstein’s seminal study The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader, rolled off the press a year later.

Abraham Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower also had a lot in common in their younger years. Lincoln had bad relations with his father Thomas, but he venerated his step-mother Sarah. Ike’s relations with his parents were remarkably similar. His father David was taciturn, and he and Ike were never close. But Ike always regarded his mother Ida as the finest person he had ever known. Lincoln and Ike were voracious readers as children. Though both possessed a streak of intellectuality, both were mischievous. Ike was the arch-prankster when he attended West Point, and Lincoln was renowned for his ribald humor and his gifts as a raconteur when he moved to the settlement of New Salem, Illinois, in his twenties.

Both Lincoln and Ike made career choices early. Ike’s decision to attend a military academy was in some respects opportunistic — both West Point and the Naval Academy charged no tuition — but his interest in military history correlated well with his decision to become a career soldier. In Lincoln’s case, his keen interest in public affairs found a natural outlet: he became a self-taught lawyer and career politician.

Both men were both innate politicians. The political instincts of Eisenhower were apparent throughout his years in the military. One of the reasons Franklin Roosevelt selected him as the commander of both Operation TORCH and Operation OVERLORD was his skill in conducting coalition warfare with America’s allies. It took brilliant political instincts to accomplish that task. The presidential king-makers were approaching Ike as early as 1943.

Despite their extroversion, both men possessed an introverted side that was haunted by very dark emotions. Lincoln struggled with depression till end of his life, and Ike had to struggle all his life with his terrible temper.

The love lives of both men were tragic, and they both had difficult marriages.

Lincoln’s first love was a young woman named Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he lived in New Salem. Their romance was dismissed for many years by historians as a legend, but a wealth of long-neglected evidence has surfaced in the past three decades that confirms the romance beyond a doubt. The untimely death of Ann plunged Lincoln into a deep and clinical depression that recurred for the rest of his life. Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon claimed right after Lincoln’s death that the loss of Ann made Lincoln incapable of truly loving any other woman: he never got over the loss of Ann. Lincoln’s marriage to Mary Todd was beset with tensions. Even so, his wife played a key role in encouraging his presidential ambitions.

Eisenhower’s first love was a girl named Gladys Harding whom he met in high school. Their attraction was passionate. But she hesitated to agree to his marriage proposal because it would mean giving up a very serious musical career to become an Army wife. Ike waited and waited for an answer to his marriage proposal, and the waiting depressed him. He finally gave up and started dating a pretty young woman named Mary — nicknamed “Mamie” — Geneva Doud, whom he met when he was stationed in San Antonio, Texas. He had no way of knowing that Gladys had reached the decision to give it all up for him. When she learned that he was engaged to another woman, she felt such despair that she impulsively married a lackluster suitor, and her marriage would be loveless.

Ike’s marriage would be troubled. He and Mamie got along very well at first, but the tragic loss of their first child, who died at age three of scarlet fever, cast a pall over their relationship. Ike wrote near the end of his life that he never really got over the loss of the child. There is also good reason to suspect that he never really got over his love for Gladys. Mamie could be cute, but Ike’s passion for Gladys was nothing less than ardent. His love letters to her — which her son released after her death — reveal that clearly.

Strains and tensions started undermining Ike and Mamie’s relationship. He was stationed for a while in the Panama Canal Zone, and Mamie found herself miserable there. Her misery was justified: their accommodations were wretched, and the hut where they lived was infested with bats, insects, and reptiles. A good deal of evidence suggests that she was pondering divorce. Later, in the 1930s, Ike was stationed in the Philippines, and Mamie refused to come along. He felt angry and betrayed, and this time he was the one to consider divorce.

During World War II he met a former fashion model named Kay Summersby, an Anglo-Irish volunteer in the British Motor Transport Corps. She became his chauffeur and then his all-purpose assistant. Before long, she was his constant companion, and rumors started flying that the two of them were having an affair. Just as Lincoln’s romance with Ann Rutledge was dismissed for many years as a myth, Ike’s affair with Kay was dismissed by historians for decades. In the course of my own research, I have become convinced that the rumors concerning Ike and Kay were true—so true, in fact, that Ike could be regarded as something of a tragic hero for giving her up. I believe she was the love of his life. Kay gave Eisenhower the adoration he had only experienced for a few summer months in 1915 with Gladys Harding. He had been missing out on that kind of raw passion for most of his adult life, and Kay gave it back to him. His sacrifice in giving up Kay must be understood as a fact of fundamental importance in his emotional development.

The contributions of Lincoln and Eisenhower to global history flowed from ideals. These ideals can be glimpsed in embryonic form in their early childhoods. But only in middle age would these ideals become volcanic imperatives with the potential to shape world history. Only then would their ambitions intersect great crises that summoned forth the full potential of their personalities. When that happened, their early ideals would define their lives’ work—indeed dominate their lives day and night.

Lincoln had a sensitive streak, a deep empathy that prompted him to write an essay denouncing cruelty to animals when he was just a little boy. In early manhood, he was ridiculed by some rough-and-tumble friends when he stopped in the middle of a horseback ride to rescue birds that had fallen from their nest. He had a penchant for interceding on behalf of the powerless—interceding in ways that would empower them. He would rescue those who were in peril, those who were oppressed—those who were enslaved.

He loathed the institution of slavery, telling his best friend Joshua Speed that the very thought of it had “the power of making me miserable.” But, like Henry Clay and others, Lincoln was convinced for most of his life that the only practical way to rid the country of slavery was to phase it out over time. He had great ambitions, and he sought the satisfactions of short-term political success. But he was also a visionary—and he pondered the long-term contingencies and hazards that might ruin the American experiment. “As a nation of freemen,” he proclaimed in 1838, “we must live through all time or die by suicide.”

As the years rolled by, his career seemed to reach an impasse and then stagnate. He served a term in Congress, and then he found himself at loose ends—an Illinois lawyer with few political prospects. But in 1854, his outrage at the Kansas-Nebraska Act wrought a change in him: he had found his life’s work. He would lead the opposition to the spread of slavery and fight the men like Stephen Douglas who promoted it. People commented at the time on his transformation: an Illinois congressman wrote of “the invisible chords of his marvelous power” and the “spell” of his “voice and presence.” Another man said that Lincoln’s voice had developed “some quality which I can’t describe, but which seemed to thrill every fiber of one’s body.”

Four years later, he delivered his House Divided speech, and by 1860, when he won the Republican presidential nomination, he surpassed all his rivals as the champion of the Free Soil movement. He became a man of destiny. And his rise to greatness had been nothing less than meteoric.

A similar pattern can be seen in the life-trajectory of Dwight Eisenhower. The vision that would make him the victorious commander and the president who would give the world peace took shape in his early childhood. But its full implications would not play out for him until middle age.

Ike’s mother was the dominant parent for him, and she was a powerful role model. His father was a sorry disappointment, so Ike went looking for surrogate father figures in his hometown of Abilene, Kansas. He found a series of manly mentors in Abilene who taught him all the manly arts: camping out, playing poker, shooting guns. The target practice merged with his fascination with ancient military history. Recent Abilene history was also a factor in his fascination with becoming a crack shot, for one of his teachers had been a deputy to Wild Bill Hickok. But there was a problem in all of this for Ike, a big problem: his mother was an ardent pacifist. So he achieved a synthesis that would guide him years later at the height of his powers: he learned to fight, but he would use this knowledge to keep the peace.

A generation before Ike was born, Abilene had been the epicenter of the early Wild West, and only lawmen like Hickok had turned the town into a decent place for people like the Eisenhowers to call home. So, Ike would emulate these men. He knew that his interest in gunplay violated his mother’s ideals, and yet he would use this knowledge to deliver his mother’s fondest wish: peace. When fights broke out on the playground at school, the other kids all knew that they could call upon Ike to restore order. And so it was that Eisenhower’s ideal of becoming a peace-keeper—the peace-keeper of the world, no less—was instilled early.

As with Lincoln, the grand consummation of Ike’s early ideal would be delayed until middle age. Like Lincoln, Ike was fiercely ambitious, and because of his powerful mind he began to get noticed by the high command after World War I. Generals Fox Conner, John J. Pershing, and Douglas MacArthur valued him as a man of supreme discretion and a brilliant staff officer. He got some top assignments in the War Department by his early forties. But then, like Lincoln, he found himself sidetracked—at an impasse. He was merely a lieutenant colonel—a battalion commander at Fort Lewis, Washington—on the eve of World War II.

Then he found his life’s work in the midst of a national emergency— like Lincoln.

World War II brought spectacular opportunities for talented officers like Ike: swift promotions would be coming their way. And so it was that just a few months after Pearl Harbor Ike became the head of the Army’s War Plans division, a top aide to Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, and a key player in the urgent strategic consultations that were taking place among President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and the British and American high commands.

By summer 1942, he was the theater commander in charge of Operation TORCH, the invasion of North Africa. By 1943, he was on the cover of Time magazine, and then FDR chose him to be the Supreme Commander at D-Day. Suddenly, he found himself a man of destiny. When the Germans surrendered, Ike was nothing less than a global hero, a man to whom people looked to keep the peace in the nuclear age. In a hero’s welcome speech that he gave in New York City, Ike proclaimed in 1945 that “peace is an absolute necessity in this world.” He had proven his skill as a warrior, but he had to prove his skill as a keeper of the peace—as a guardian. And the only way to do it was to rise to the presidency.

Both Lincoln and Ike had to call upon their skills as Machiavellian strategists in the White House. And they both made use of deception.

The quintessence of Lincoln’s grand deception was to give the impression that saving the Union was his overall objective while the issue of slavery was secondary. But the truth was completely the reverse. It was Lincoln’s stand on slavery that caused the rupture in the Union. His election was the death knell for slavery. The Republican platform in the presidential election of 1860 promised to halt its expansion. No more slave states would ever be created if Lincoln and the Republicans had their way. That meant that the existing bloc of slave states would be greatly out-numbered as more and more free states entered the Union. When a free-state majority reached three quarters, an anti-slavery constitutional amendment could be ratified. And that was exactly how slavery would be brought to an end by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

The leaders of the slave states foresaw this. So as soon as Lincoln was elected president, the secession movement began. A frantic attempt would be made in the lame-duck Congress to halt it with a constitutional compromise to permit the continued extension of slavery. This was known as the Crittenden Compromise. Lincoln shot it down—but since he killed the compromise in secret, the public never knew. In letters marked “private and confidential,” he told Republican leaders to destroy the Crittenden Compromise. “Hold on as with a chain of steel,” he wrote. These facts must be distinctly understood to grasp the nature of the Lincoln myth—a myth that he created himself.

In August, 1862, he wrote his famous open letter to the editor Horace Greeley proclaiming that “my paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery.

If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all of the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” Americans are fooled by that letter to this very day. It was a brilliant trick—a deception. If Lincoln’s paramount object were to save the Union, why did he destroy the Crittenden Compromise? He should have backed it energetically.

But he didn’t.

The Union would not have been placed in jeopardy in the first place if it were not for Lincoln’s stand on slavery. It was his non-negotiable objective of halting the expansion of slavery that triggered secession. And he responded to secession with vigor. He fought to preserve the Union, yes, but consider the flip side of that proposition: in “saving the Union,” he was also destroying the new slave-holding nation that secessionists were trying to create. He would smash that new slave-holding nation—the Confederacy—like a snake in its egg. Most Americans had no idea at the time that Lincoln had destroyed the Crittenden Compromise because he did it in secret, so his letter to the editor sounded convincing. Moreover, he wrote the letter in part to pave the way for his Emancipation Proclamation—already written in secret—by getting northern voters used to the idea that to save the Union he might have to start freeing some slaves.

As he urged his generals to fight total war, he expanded the aims of the war to promote the empowerment of Black Americans, and he was doing that in secret as well. As his troops took over Confederate states in 1863, Lincoln told his commanders to get Unionists in those states to redraft their state constitutions in order to turn them into free states. He made it clear that his own role in the process would be kept carefully hidden, to preserve deniability. It was only the scholarship of LaWanda Cox that began to reveal this remarkable story in 1981.

Lincoln has gone down in history as the author of the “Ten Percent Plan,” the supposedly “lenient” Reconstruction plan that would give a mere ten percent of the voters in rebel states the power of home rule once they had taken oaths of loyalty to the Union as well as to the Emancipation Proclamation. Lenient? It was quite the reverse: it was a pushy and high-handed scheme to force emancipation down the throats of pro-slavery majorities in southern rebel states. It was a trick. And the key was the oath to support the Emancipation Proclamation. Southern whites who wanted amnesty and the right to vote would have to do more than just swear an oath to the Union. They would also have to swear an oath to support the Emancipation Proclamation.

The gist of it all came down to the following fact: only anti-slavery whites would be allowed to vote. If you could not take an oath on the holy Bible to support emancipation, you were not allowed to vote. In other words, only anti-slavery whites would be voting, and it would not take many of them—only ten percent of the state’s population—to overpower the wishes of a ninety percent pro-slavery majority. Then the ten percent could go on to draft and ratify a new state constitution abolishing slavery forever. Lincoln’s mastery of illusion—his ability to hide secret actions and to make his policies appear the reverse of what they were—was a demonstration of true Machiavellian genius. The presidency of Dwight Eisenhower was suffused with the very same genius.

After Ike left the presidency, he consented to some televised interviews with Walter Cronkite. When Cronkite asked him to name his best presidential achievement, Ike said that it was giving the American people serenity. And to do that, he used a deception.

Since he had always been consumed with inner rage—since he had always had a terrible temper—he had to appear to be relaxed when he really wasn’t. He had to pretend to be the opposite of what he was. He had to project a sunny and relaxed personality, when behind the scenes he was an angry and impatient executive with a razor-sharp mind: an iron-willed commander who did not suffer fools gladly. To achieve the self-control that was needed to create this illusion, he developed a secret routine. He created a White House ritual that everybody understood: presidential aides could be summoned to the Oval Office at any time, and their job was to stand there and listen in silence while he cursed a blue streak. Ike grinned from ear to ear as he explained this method to Cronkite.

Ike’s aim in his presidential years was to create good feelings while making tough-as-nails decisions to prevent World War III. He was careful to leave no traces when it came to his most secret programs. Indeed, the only way that we know about some of these programs is through oral history interviews conducted by historians. One of these historians, R. Cargill Hall, was the chief historian for the National Reconnaissance Office, an agency so secret that its very name was kept secret for years.

Ike gave the American people a decade of peace and security, a guardianship that only he and a small inner circle could comprehend. He also pioneered an ethos in government that would serve the nation well for many years. When asked by a journalist after leaving the presidency to summarize his best presidential achievement, Ike had this to say: “The United States never lost a soldier or a foot of ground in my administration . . . . People ask how it happened—by God, it didn’t just happen, I’ll tell you that.”

When Eisenhower ran for the presidency in 1952, the United States was fraught with hysteria. Demagogues like Joseph McCarthy had convinced huge numbers of Americans that their government was infested with traitors. Americans were fearful, angry, and prepared to retreat into isolationism—the kind of isolationism that prevailed before World War II. World War I had been sold a generation earlier as the “war to end war,” and of course it was no such thing. World War II, in the minds of many people, was the war that was supposed to “finish the job”—but it didn’t.

Only five years after the defeat of the Axis, American soldiers were fighting in Korea, and many concluded that only one thing—a betrayal—could explain this state of affairs. When Eisenhower ran for the Republican nomination, he had to defeat an unrepentant isolationist, Senator Robert Taft. Ike ended the unwinnable war in Korea, and he built up a strategy of nuclear deterrence to prevent war from breaking out elsewhere. It was all done quietly, methodically, behind the scenes—in secret.

Within a few years, he created such an age of good feelings that Americans were proud of the fact that their country was taking its place in the world as a permanent superpower. They were proud of the fact that their nation was “the leader of the free world.” And to keep the United States a super-power in economic terms—while preventing another depression—Ike launched the greatest public works project in American history, the Interstate Highway System. In this case, he acted in the open—and yet this epochal project was launched with minimal fanfare. Here was a project that FDR would have envied, but how many Americans today remember—or even know—that Ike created it?

Quietly, systematically, he worked behind the scenes to reduce the tension in American life while promoting social change with his “hidden-hand” methods. He engineered the downfall of Joseph McCarthy through hidden maneuvers. He nominated Earl Warren as chief justice of the Supreme Court, knowing perfectly well that he favored public school integration. Then he followed up by packing the courts with integrationist judges to make certain that the Brown v. Board of Education decision would be enforced. And in deepest secrecy, he gave orders to develop the capacity for space-based reconnaissance.

Ike was a visionary: he developed in secret a vast array of programs to protect Americans, while building the country’s prosperity, cohesion, and power.

All the while he gave the misleading impression that his own life was totally relaxed. He could create the impression that his mind was so completely relaxed that his thinking was imprecise and fuzzy. He would even go so far at certain times as to play the fool—he would put on an act at his own expense—to achieve deception. On one occasion, his press secretary James Hagerty warned him that a dangerous question might be coming his way at an upcoming press conference. Ike smiled at him and said, “Don’t worry, Jim, I’ll just confuse them.” His answer at the press conference was a masterpiece of comic circumlocution, a rambling rumination that was almost incoherent. It was all quite deliberate: an evasion to preserve his maneuvering room. Who else would diminish his own reputation to achieve his policy goals? Who else? Only Lincoln.

On January 20, 1862, abolitionists called upon Lincoln at the White House. They urged him to expand the aims of the war in a manner that would strike down slavery. Lincoln encouraged them. And to work with them in a synergistic manner, he told them to whip up public sentiment—against himself. “You can go home and try to bring the people to your views,” Lincoln told his guests, “and you may say anything you like about me, if that will help. Don’t spare me!” In other words, Lincoln told his allies to trash his own reputation—to accuse him of being slow, dull-witted, and uninspired—to increase public pressure in a way that would justify the stronger measures he was planning. Like Ike, Lincoln was prepared to sacrifice his own reputation to create more maneuvering room and more leverage.

In these two men, we see a fascinating historical accomplishment: ambition brilliantly sublimated into self-sacrifice. There was more—much more—to their achievements than meets the eye, much more than most Americans know. We can only hope that their legacy will help to redeem our troubled land and create a better future for us all. Let us pray that it will.

Richard Striner is the author of over a dozen books. His new book on Eisenhower—Ike in Love and War: How Dwight D. Eisenhower Sacrificed Himself to Keep the Peace—will be published in October 2023.

This paper was presented as the 39th Annual Abraham Lincoln Lecture at Louisiana State University/Shreveport on October 22, 2022.