Interview with Jason Emerson Regarding his new book, “Mary Lincoln for The Ages”

Interview with Jason Emerson Regarding his new book, “Mary Lincoln for The Ages”

Sara Gabbard: Your book is defined as “an analytical bibliography.” Please explain how you chose this particular approach.

Jason Emerson: This approach — this entire book, in fact — really just came about organically. While I was preparing for publication an edition of a previously unpublished manuscript about Mary written in 1927 (Myra Helmer Pritchard, The Dark Days of Abraham Lincoln’s Widow as Revealed by Her Own Letters, published by Southern Illinois University Press in 2011), I wondered where that book, if it had been published at the time, would have fallen in the timeline of works about Mary Lincoln. I started to create a simple bibliography, and the more I dug for resources the more I realized that no extensive bibliography of Mary Lincoln had ever been done. So I decided to do one myself because I thought it would be fun and I thought it would be a great addition to Mary Lincoln scholarship. I decided to make it analytical (originally I called it “annotated” but my editor at SIU Press, Sylvia Frank Rodrigue, suggested that “analytical” was a more accurate description) because, in my experience, people refer to books and articles about Mary all the time without understanding the true value or accuracy of the references. I wanted to offer up descriptions and analyses of the works to help people know what the references truly say and what I, as a Lincoln scholar with more than 20 years of research and experience under my belt and the person who has researched and published more about Mary Lincoln than any other scholar ever, think about them.

After probably a year or two of work in 2008-2009, I created an annotated bibliography of 243 entries of every genre of writing about Mary (nonfiction, fiction, poetry, plays, juvenilia), which was published as an article in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society in summer 2010. I had so much fun with it that I couldn’t help but keep looking for more items to add to the list, and I subsequently published a supplementary annotated bibliography with thirty-four additional entries one year later, also in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. After that, I really delved deeply and wanted to discover the more obscure and hard-to-find writings on Mary; I also began adding to my list items I purposefully had omitted from my two articles for various reasons.

Finally, I decided to just make the list inclusive of every source I could find and seek to create a definitive analytical bibliography that would enhance Mary Lincoln scholarship by offering a map of sources that future scholars could reference during their work. Now that I think about it, this entire project was a pretty massive undertaking, on which I spent a total of about 10 years.

SG: Your research is incredible. How did you organize the book’s outline?

JE: I started with the analytical bibliography, which was originally going to be the entire book. The years of reading over 450 works about Mary (over 300 of which were nonfiction), however, ended up giving me new insight and understanding about Mary’s reputation and legacy (both while she lived and after she died), as well as about how she has been interpreted and perceived for the past 150 years — and which works about her have created and fed those interpretations and perceptions. This led to my writing the first part of the book, “The Common Canon of Mary Lincoln,” where I discuss and deconstruct this subject.

The final component of the book, the multiple indexes, was also a suggestion of my editor, based off David J. Eicher’s 1996 book, The Civil War in Books: An Analytical Bibliography. Creating separate indexes for titles, authors, and subjects of the 452 entries in the analytical bibliography was a way to make the book more user friendly and therefore a better resource. So what I thought would be a smallish book comprised of a brief introduction and an analytical bibliography ended up being a much more thorough and valuable work (and it ended up taking me a lot longer to do!)

SG: I have always been fascinated by changing perceptions of people and events as each new generation of historians focuses on a particular subject. Has “coverage” of Mary Lincoln changed through the years?

JE: Definitely. The way people today perceive Mary Lincoln is far different from the way she was perceived during her life and shortly after her death. At first, she was nothing more than Abraham Lincoln’s wife, a minor side character to his story. She was the loving little woman by his side, described by her physical appearance and her wardrobe, and the fact that she kept the clean and loving home within which a great man dwelled as he rose to prominence.

It was not until nearly the turn of the century that Mary Lincoln became seen as a historical figure in her own right. This started with articles and books written by Todd family members seeking to clarify and somewhat rehabilitate Mary’s place in history. At that time, Mary was straddling the line between being the practically anonymous side character of “Abraham Lincoln’s wife” and having a greater historical identity as “Mrs. Abraham Lincoln,” the president’s companion and partner who also had her own life.

It was not until 1932 that the first objective books on Mary Lincoln were published by writers who sought to give readers an unalloyed, professionally-approached examination of her unique character and historical life. In the 1940s and 1950s, Mary grew fully into the character of Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. True to the social mores of the time, Mary began being seen and interpreted as a June Cleaver-type character of wife, mother, and housekeeper, but also a solid companion for her husband without whom he would not be complete.

By the 1980s, with the rise of feminist revisionism, biographical work on Mary Lincoln went in a new direction, and with it, Mary as “Mrs. Abraham Lincoln” gave way to her being identified and recognized as “Mary TODD Lincoln”—her own woman, a woman ahead of her times, a woman apart from her husband with her own ideas and strengths who was battling against a patriarchal society. (And as a side note: Mary never used her maiden name after she was married. Everything she signed was either “Mary Lincoln,” “Mrs. Abraham Lincoln,” or simply “ML.” The addition of the “Todd” to her full name started in the 1980s by historical revisionists as a way to give her own separate identity.)

Since the turn of the millennium in 2000, Mary has become a feminist icon — her reputation is that she was actually the brains behind the bumpkin Lincoln, she wrote his speeches and advised him on policy and she was really Hillary Clinton 150 years too soon (an interpretation with which I strongly disagree, and which I think Mary herself would find ridiculous).

I’d like to think the interpretation of Mary is now swinging back more towards reality — that she was an amazing woman in many ways, but who was still a product of her time (not of the 20th or 21st century) , and who had very real flaws and problems that created issues not only for herself but also for her husband. I don’t believe it is inappropriate, insulting, or belittling to Mary’s legacy to understand and illuminate the negative aspects of her character along with the positive aspects. Mary was not perfect; she was, quite simply, human, and if we want to understand the totality of her, we cannot ignore or evade the painful truths of her shortcomings. And I think people are beginning to realize that.

It’s interesting to me that so many books and articles love to point out Abraham Lincoln’s flaws, challenges, and shortcomings (a common one of which is that he had to deal with this “horrible” wife) and use those to then portray him as an even greater man than everyone thinks because he achieved all he did while overcoming those obstacles. And I agree that overcoming life’s challenges is an integral part of someone’s character. However, when it comes to Mary Lincoln, her flaws are either ignored, or portrayed not as things she dealt with and overcame, but as things that just prove she was an annoying woman not worthy of her husband. We have to destroy this dichotomy and show Mary was the whole person that she was.

SG: A note from your publisher states: “Emerson changes the paradigm of Mary Lincoln’s Legacy.” Was this your original intent or did your research lead you to it?

JE: This was not my original intent. As I mentioned above, the research definitely led me to it. After reading all the sources I found, over 300 of which were nonfiction articles and books about Mary, some of which contained items of which I had never even heard, I realized that almost everyone — historians, general writers, book reviewers, journalists, playwrights, etc. — use the same few sources to research and write about her. (Of course, scholars should always go to the original sources in archives, but few of us can do that, and most people find their information in printed materials, which is why I focus on them.)

I find that almost everyone uses the same seven basic sources when they research Mary — that is two percent of all the known writings about her. Two percent. If I were being generous, I might go up to as high as saying there are fifteen sources everyone uses, but really it is the basic seven: The books by William Herndon, Elizabeth Keckley, Katherine Helm, Ruth Painter Randall, Justin and Linda Turner, Jean Baker, and Mark Neely and R. Gerald McMurtry. As I state in my book, if Mary’s life is always written with the same stories, from the same sources, under the same predilections and presuppositions, then it is not her true legacy. Her story over the past many decades has become monochromatic, flat and shallow, with no new facts or insights to revitalize scholarship about her.

To think that Abraham Lincoln is one of the most written-about people in world history, and his wife, whatever you think of her, was an integral part of his life (as anyone’s spouse would be, for good or ill), why is research into her life so stagnant? Why do so few people care enough about who she was to try to understand her better than looking into surface stories that may or may not be true? As a historian, I find this unconscionable. So in my book I discuss and dissect those seven works about Mary and how they are — or are not — worthy sources about her life, and then I offer up a catalog of secondary sources people should be using to interpret Mary’s life, as well as subjects within her life that need more research and discussion. I’d like to think this book opens up a new roadmap to understanding Mary Lincoln, and will spark much discussion.

SG: Did you find evidence that perhaps Mary Lincoln was more popular in Washington than we have frequently been led to believe?

JE: No; I think Mary was just as unpopular in Washington as we all have typically come to believe. But I found more evidence as to why she was so unpopular, which is, I think, a critical understanding to have when looking at this part of her life.

To begin, I agree with biographer Ruth Painter Randall who said Mary simply could not win in Washington, no matter what she did. Northerners thought she was a traitor and a spy because she grew up in Kentucky; southerners thought she was a traitor who abandoned her homeland and married an abolitionist northerner; Easterners thought she was an uncouth rube unfit to be First Lady because she was from the west; and political wives and general female society in Washington, DC, disliked her because she was not one of them and had never really been one of them. On top of that, Mary was a strong-willed and intelligent woman who did not genuflect to DC society and listened to her own opinions — not anyone else’s — about how best to do her work as First Lady, which the women (and men) in DC society also resented.

Also Mary’s writings and actions — and the writings of her contemporaries — show that she believed herself — especially during the first year of her role as First Lady — to be the queen of America and of capital society, and she expected and demanded that everyone treat her as such. She looked down on many important people in society as beneath her and her husband, and this was not something capital society was accustomed to, or was willing to tolerate.

I think Mary’s unpopularity in Washington during the war was a result, in part, of the arrogance and traditions of the DC that she moved into, and also Mary’s own fault through her own bad behaviors and narcissistic tendencies.

As presidential secretary William O. Stoddard also observed, Mary did not utilize the press to her full advantage to show the positive actions she took as First Lady, which continued her poor reputation, and then when she shut out the press for whatever reason they wrote even more stories portraying her in a negative light.

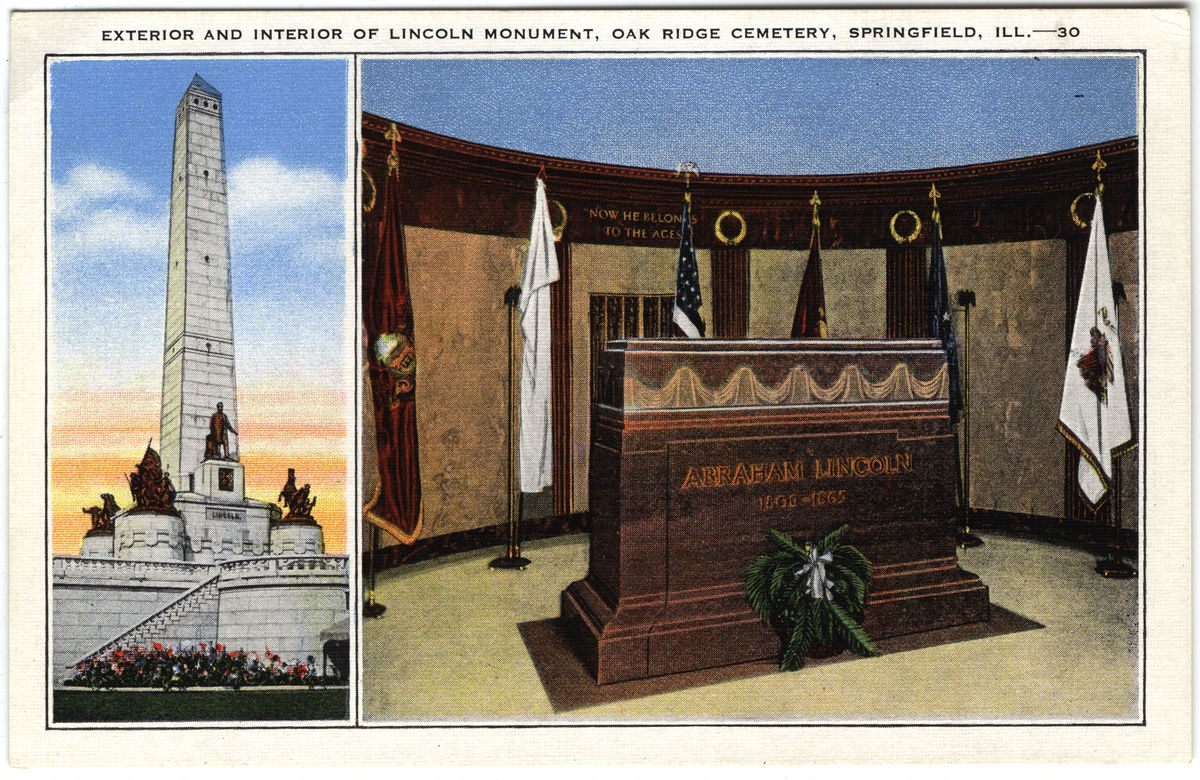

SG: Please explain the conflict over Lincoln’s burial site between his widow and the Lincoln Monument Association in Springfield.

JE: After the assassination, a burial/memorial committee was formed in Springfield, Illinois, and a burial place purchased in the middle of the city and construction on a grave begun without consulting Mary Lincoln. When she learned this (through the newspapers) she was outraged. She intended — and insisted — her husband be buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery, two miles outside the city, where he previously told her he wanted to be buried. When the committee refused, Mary threatened to take her husband’s remains away to Chicago, or to the crypt prepared for President George Washington under the U.S. Capitol building that was never used. The committee, reluctantly and angrily, relented, and the citizens of Springfield, who, according to many at the time never really cared for Lincoln’s wife anyway, were incensed that she did not bow to their wishes about where her husband would be buried.

But then a few weeks later, the Lincoln Monument Association decided, again without consulting Mary Lincoln, that the official monument to Lincoln would not go over the tomb (as everyone expected) but rather on the city plot they previously bought. Mary again demanded her wishes be respected and the monument be placed over the grave. The committee argued with her and refused, unwilling to let her win again. They traveled to Chicago to discuss it with her, but she refused to see them. She again said if they ignored her, she would take her husband’s body for burial someplace else, probably Chicago. The committee took a vote, and agreed to Mary’s demands by only one vote. I have no doubt that if the Springfield committee, who so arrogantly ignored Mary’s wishes and grossly underestimated her strength, had voted the other way, Abraham Lincoln’s tomb today would be in Chicago and not in Springfield.

SG: It has been reported that Mary Lincoln and William Herndon were frequently engaged in conflict. Do you believe that to be true? How much of Mary’s negative image can be traced to Herndon?

JE: For years I believed (without truly examining) the notion that Mary and Herndon hated each other from the moment they met at a dance and he told her she moved with the ease of a serpent — which in his mind was a compliment but which she found insulting. But I think historian Douglas L. Wilson proved convincingly in his 2001 article “William H. Herndon and Mary Todd Lincoln” that the two were on friendly terms until 1866 — until, that is, Herndon gave his now-infamous lecture stating that Ann Rutledge was the love of Abraham Lincoln’s life. After that, Mary certainly hated Herndon, but after reading Wilson’s article and examining the evidence myself, he is exactly right that there is no contemporary evidence showing bad blood between them before 1866. Herndon’s letters show that even in his later writings, in which he shows Mary in an often negative light, he brought out these painful truths about her because he believed he was helping her. As he said multiple times, yes she was a “she-devil,” but Lincoln really drove her to her behaviors because he never truly loved her, and she had to live with that painful knowledge; and it was better that the public hear this from a family friend who could explain that her character was the result of heartbreak and Mr. Lincoln’s rather cold character.

I do believe that much of Mary’s negative image can be traced to Herndon and his writings, especially his biography of Abraham Lincoln. But, as I stated above, Herndon always said he revealed these truths out of a sense of duty and honor and not out of any antipathy for Mary Lincoln. So I like to warn people that Herndon’s book is not for the uninitiated. Much of what he states as fact (about both Mary and Abraham Lincoln) should not be outright believed because he was such a peculiar character, he had so much arrogance about the accuracy of his intuitions and insights, that he is not always reliable. You have to understand his character and perceptions, his motivations, and especially his interview subjects and techniques when he sought out information on the Lincolns.

SG: I always like to ask a scholar: In your research was there new material which surprised you? Was there material which made you think, I never thought of it that way? Was there material which simply confirmed a previously held opinion?

JE: What surprised me was how much original material there was printed on Mary, in books and articles and newspaper stories, that is either unknown or completely ignored; what also surprised me was the realization that, as I stated above, most people use the same few, modern sources about her to try to understand her life. I found so many interviews and reminiscences about Mary from her family members and friends that no scholars have used at all in their works, as well as some very insightful interpretations about Mary written by multiple scholars. I found what is now one of my favorite quotes about Mary Lincoln: Herbert Mitgang wrote of her that she is “an enigmatic daguerreotype sitting uncomfortably in the shadow of her husband.”

I was surprised to find a number of primary source materials that explained Mary Lincoln’s life and character that I did not know existed, even though what was in those articles has been used by multiple writers — those writers all, however, tend to use stories used by previous writers, but none of them ever cite the original source for the information.

I was astonished by the large number of medical studies and writings about Mary that I found that were unknown or unused by scholars, including a study on the effect of the probable concussion Mary suffered in her 1863 carriage accident and a recent look at treating her many ailments using acupuncture. I was also surprised (and disappointed) by the facts about Mary I did not find, mainly the fact that nobody has ever really gone to Europe to search through archives in the countries where Mary lived for nearly a decade.

I think I learned more about Mary’s relationship with Herndon through my research, as mentioned above, and the extent to which Mary visited wounded soldiers in Unions hospitals was far more than I ever knew — and did not really start until after her son Willie died in 1862. I also found much information I had never seen about Mary’s belief in Spiritualism (and Abraham Lincoln’s experiences with it) — in particular I was excited to find two writings by spirit photographer William Mumler about the day he took Mary’s picture (the now famous spirit photo of her with Abraham’s ghost standing over one shoulder and Tad’s ghost standing over the other). Most people have read Mumler’s account of this as published in his 1875 memoir many years after the fact (and very embellished), but what excited me was finding an article he wrote only two months after he took the photo in The Spiritual Magazine in which he described Mary’s visit — and it is a much different story than what he put in his memoir three years later.

Basically, doing this analytical bibliography of Mary gave me a vast education, a slew of new insights, and an altered perception on who Mary was — and on who we think Mary was and based on what sources we think we know this.

SG: Probably not a fair question, but: In spite of all of the negative comments about Mary Todd Lincoln through the years, would her husband have become the man we so admire without her?

JE: Haha, that’s a tough one! Yes and no. Lincoln was already an ambitious and successful political animal when he met Mary, and there is no indication he was intending to give it up. So I do not believe she created his political drive and greatness. Similarly, he was already a lawyer and intent on being the best lawyer he could be, so her presence in his life did not create his legal greatness either.

On the other hand, all spouses impact the lives of their significant other, that is undeniable and inarguable. Mary certainly improved Abraham’s social skills, and everyone who knew her agrees that she had a certain acumen about reading the character and motivations of other people, and she would share her perceptions with him, which probably helped him navigate certain social, legal, and political situations. There are many who knew Lincoln — Herndon being the major one, but also many other lawyers and politicians — who later said that Mary did push her husband to action many times when he was content to sit still; that she encouraged him to run for high political office and believed in him when he did not believe in himself. If Lincoln had married someone else, someone less ambitious for him (or for herself) he may not have become president; he may instead have become a state senator or governor of Illinois, and kept his political ambitions more local.

Also, Mary was an extremely emotional and, I believe, bipolar woman, who did cause Lincoln incredible amounts of stress and worry over the years, particularly when he was president. Many of Lincoln’s contemporaries as well as later scholars have attributed the development of Lincoln’s patience and magnanimity as president to dealing with his wife’s erratic behaviors for so many years. I think that is not an inconceivable idea.

In short, no: Lincoln would not be the man we know and admire today if Mary Todd had never entered his life — that is human nature and the nature of marriage. Any marriage. The main question to me on this is the degree to which she influenced and impacted his life that helped him change from the prairie lawyer in 1841 to the American president in 1861.

Jason Emerson is a journalist and historian who has researched and written about the Lincoln family for more than twenty five years.