An Interview with E. Lawrence Abel on Lincoln’s Assassination

An Interview with E. Lawrence Abel on Lincoln’s Assassination by Sara Gabbard

An Interview with E. Lawrence Abel on Lincoln’s Assassination

Sara Gabbard: Your book, A Finger in Lincoln’s Brain, presented a detailed analysis of the medical measures which were used after John Wilkes Booth shot the 16th President. Today those measures seem almost primitive in nature. Given the status of medical knowledge in 1865, did the doctors do the best they could?

E. Lawrence Abel: Yes they did, but even if Lincoln had the slightest chance of surviving, albeit totally incapacitated, they doomed him. Charles Augustus Leale, the first doctor to treat him while he was still at Ford’s Theatre, followed the standard method in military textbooks of the day for treating gunshot wounds to the head. After laying Lincoln on the ground, to avoid “syncope,” a sudden loss of blood pressure that would lower blood flow to Lincoln’s brain, he examined Lincoln’s body for a wound. When he found none, he examined his head and found a round, smooth bullet hole on the left side of Lincoln’s head, behind his ear. In accord with the medical standard of care for that time, Leale inserted his little finger into the wound to determine if he could remove the bullet, and thereby relieve the pressure inside Lincoln’s brain. Unable to feel it, he drew his finger back out.

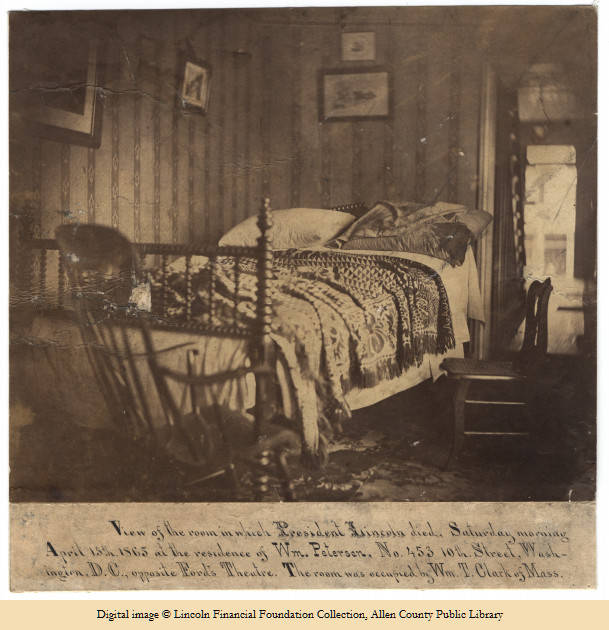

After Lincoln’s body was removed to the Petersen house across from Ford’s Theatre, two other doctors also stuck their fingers into the wound in his head to see if they could touch the bullet, but it had penetrated far beyond the depth of a finger-tip. Since the bullet has passed beyond the finger, three doctors tried to locate it with a probe, but they too could not make contact with the bullet.

In inserting their fingers or a probe into Lincoln’s wound, these medical men were following protocol. The aim was to relieve the pressure inside Lincoln’s brain using the only methods available to locate the bullet and extract it, if in deeper than a finger, by trephining—cutting a hole in Lincoln’s skull and removing the bullet from his brain. Even had they done so, Lincoln would never have recovered from the physical damage caused by those finger and metal probes, and from the infections from those fingers and probes. This was a time before medicine recognized germ theory, so those doctors should not be faulted on that score.

SG: Describe Major Rathbone’s attempt to capture the assassin.

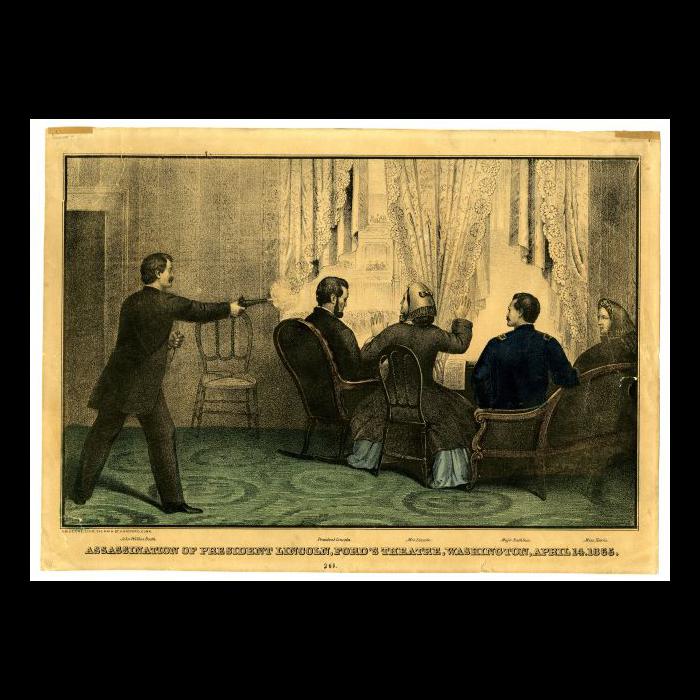

EA: Lincoln, Mary, and their two guests, Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone were sitting with them in the Presidential box at Ford’s Theatre when John Wilkes Booth entered the box and shot Lincoln. Major Rathbone was seated on a sofa at the back of the box in such a way that his back was facing the door through which Booth entered. When he heard Booth’s gun fire from behind him, he turned and sprang at the assassin. Booth turned to face his attacker and would have stabbed him in the chest, but Rathbone parried the blow and was slashed on his left arm between the elbow and his arm pit. The knife cut through his biceps, just missing his brachial artery.

With Rathbone momentarily stepping back from the pain in his arm, Booth ran to the railing in front of the box. As he was making his jump, one of his spurs caught in the folds of a flag that had been draped over the railing, causing him to fall awkwardly onto the stage, and crack the fibula bone in his lower leg. As Booth landed on the stage, Rathbone shouted from the railing “Stop that man!” and Clara Harris frantically screamed, “The President has been shot!”

SG: Describe the scene at Ford’s Theatre when it became obvious that the president had been shot:

EA: Despite cracking the bone in his leg, Booth quickly recovered and got to feet. Brandishing his knife in the air, he shouted “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” (“Thus always to tyrants!” Virginia’s state motto), and then “The South is Avenged,” and limped across the stage and made his getaway.

Henry Hawk, the lone actor on the stage, saw Booth coming toward him and ran for cover. The audience heard the shot and was momentarily struck dumb until shaken out of its daze by Rathbone’s and Clara Harris’ screams. Sitting in the front row of the orchestra seats at stage level, Joseph Steward was one of the first to react and leapt onto the stage to catch the fleeing assassin, but he was too far behind. Most of the others in the theatre panicked. In the pandemonium that followed, many people desperately raced toward the exits, shouting, smashing seats, and trampling over one another, trying to escape what many believed was a Confederate attack. It was the “hell of hells,” said one of the women in the audience that night.

SG: Was it simply too risky to seek a better place to move the wounded man than the Petersen house?

EA: Moments after Dr. Leale began treating Lincoln, two other doctors, Dr. Albert King and Charles Sabin Taft made their way into the Presidential box. After Lincoln’s condition appeared to stabilize, the three physicians discussed moving him to somewhere more commodious. Their first thought was the White House. But that was seven blocks away and Lincoln might not survive the jostling trip through Washington’s deeply rutted streets. Instead, they decided the best place to move him would be to one of the houses across the street from the theatre. After it was determined that no one in the house directly across from the theatre was home, Lincoln’s body was carried a few houses down the street to the Petersen house where he died the next morning.

SG: You wrote an article “The Shot That Killed Lincoln” in the Surratt Courier (September 2015) questioning the common assertion that Booth shot Lincoln at “point blank” range. Please explain your argument.

EA: In nearly every account of the assassination, Booth is said to have fired at “point blank” range, implying that Booth’s gun was in contact with the back of Lincoln’s head or a few inches or no more than two feet away Booth pulled the trigger.

When Lincoln was examined after being taken to the Petersen House, the hair on the back of his head was not found to be singed nor were there any powder burns at the back of his head, as there would have been had Booth fired from less than two feet away.

That does not rule out the possibility of a hard contact wound, however. A shot from a gun pressed directly against the head forces the hair around the wound directly into the head and seals the tissues around the entry wound. There is also no soot or powder on the surface because the combustion gasses and powder from the shot are also driven into the wound rather than deposited on the surface. The shot could not have been a hard contact wound because the wound was not sealed, as indicated by the fingers and probes Dr. Leale and the other physicians inserted into it.

Eye witness testimony also indicates that Booth fired from just inside the door of the Presidential box. The distance from the inside the door to the chair Lincoln was sitting in is about four to five feet (Laura Anderson, Curator of Ford’s Museum, personal communication). Major Rathbone testified that he heard the discharge of a pistol behind him. As previously noted, Rathbone was sitting at the far end of a sofa close to the door. According to James Ferguson, the only witness to be looking up from the audience at the Presidential box at the moment Lincoln was shot, the flash from Booth’s gun in the darkened Presidential box came from the back of the box. Had Booth been holding the gun against Lincoln’s head, Ferguson could not have seen the flash.

According to Dr. Leale and another of the physicians who stuck their finger into the wound, the entry was smooth and circular. According to Ferguson, Lincoln was leaning over the railing from his high-back chair and looking to his left. If Booth were standing behind Lincoln, the bullet would have entered on an angle, creating a ragged, sharp entry wound. The only possibility for a smooth round entry wound, with Lincoln’s head turned to the left, was a perpendicular shot, I.e. if Booth fired from Lincoln’s right.

The forensic and eye witness testimony all support the conclusion that Lincoln was not shot at point blank range but rather from the back of the Presidential box.

SG: In that same article you suggested the provocative thesis that Booth’s shooting Lincoln in the head was a “lucky shot.” Please explain your reasoning

EA: Booth’s shot to Lincoln’s head is usually attributed to often cited accounts of his marksmanship. But those accounts refer to this skill with revolvers. Booth’s gun the night of the assassination was a derringer, a “junk gun” with considerable recoil. The only time Booth was seen to fire a derringer, he missed the target from only a few feet away. There is no evidence other than that incident that Booth ever fired a derringer.

Taking into account that Lincoln was leaning over the railing when he was shot, that Booth fired from about five feet away, that he would have fired in haste, the inherent inaccuracy of his weapon and its considerable recoil, it is not improbable that Booth was aiming not at the smaller target of Lincoln’s head, but at the larger target of his back. In other words, when Booth aimed his gun and fired, he missed his target. The bullet that entered Lincoln’s head was a “lucky” shot for Booth and an unlucky shot for Lincoln.

E. Lawrence Abel, the author of A Finger in Lincoln’s Brain, is a professor at Wayne State University.