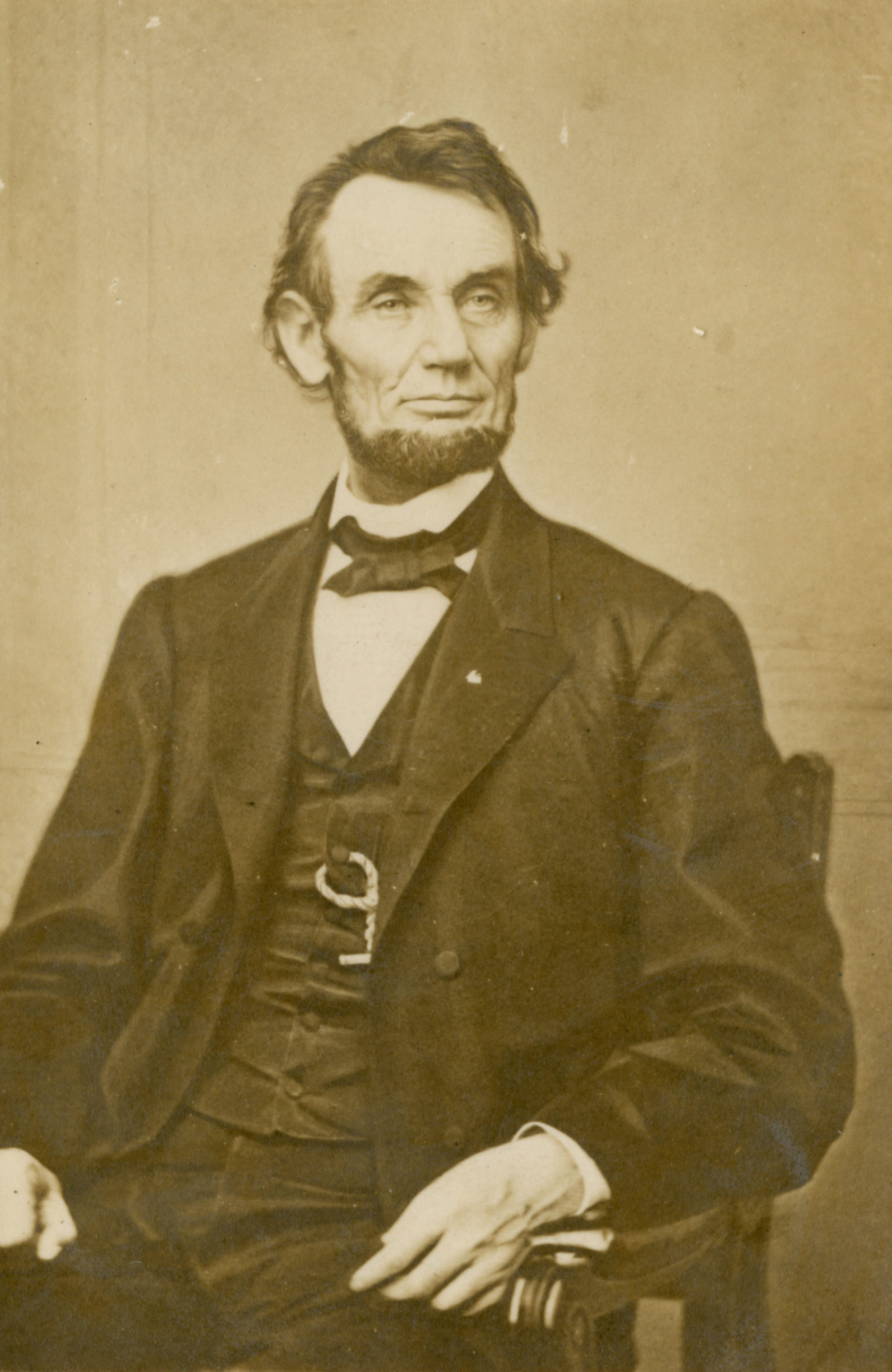

The Long Twisting Road: Abraham Lincoln’s Evolving World with the Foreign Born

Immigration? Abraham Lincoln? Absolutely. Lincoln lived in an era when immigration was as much a controversial matter as it is today. Between 1840 and 1860 four and a half million newcomers arrived, most of them from Ireland, the German states, and Scandinavian countries. Many more crossed back and forth across the border with Mexico, newly drawn in 1848.

From an early age, Lincoln developed awareness and a tolerance for different peoples and their cultures. While no doubt a product of his time, Lincoln nevertheless refused to let his environment blind him to the strengths of diversity, and throughout his legal and political career he retained an affinity for immigrants, especially the Germans, Irish, Jews, and Scandinavians. Indeed, immigrants and their plight were never far from his thoughts or plans. His travels at a young age down the Mississippi River to the port of New Orleans exposed Lincoln to the sights, sounds, and tastes of a world hitherto he could only have dreamed about. More importantly, however, it established a foundation and sympathy for the rest of his life when it came to the foreign-born, as well as to the enslaved.

Lincoln’s two flatboat voyages to New Orleans were exceptionally important in his development. They formed the longest journeys of his life, his first experiences in a major city, his only visits to the Deep South, his sole exposure to the region’s brand of slavery and slave trading, his only time in the subtropics, and the closest he ever came to immersing himself in a foreign culture.

Lincoln’s flatboat journeys exposed him, for weeks on end, to the vastness of the American landscape. No subsequent travels would ever match the length of those journeys. They immersed him in the relationship between transportation and economic development in the West. He understood and preached that a better transportation system would improve the economic life of Illinois, raise living standards for all and enhance property values. Lincoln’s river journeys also illustrated to him that by controlling the unsettled domains in Illinois, the state could accelerate immigration. Residing in a sparsely populated region, it is understandable that wealth and population were practically synonymous for him. Immigrants would bring economic growth and all that it implied. Indeed, seeing America firsthand from a flatboat at a young age transfixed on Lincoln the core Whig social and economic philosophies such as free labor, transportation modernization, internal improvements, and most assuredly, the need to attract immigration.

Like so many in the mid-nineteenth century, Lincoln’s philosophy about immigrants was far more complicated than merely that which pertained to the free labor economy. Abraham Lincoln was a product of his times and his environment. And despite whatever economic advantages an immigrant might represent, many men of his era saw every ethnic group, every immigrant, whether Irish, Jewish, German, or Swedish, as monolithic. Yet Lincoln tended to perceive each individual and each group as distinctive in its own right. Whether it was the Germans or Jews who politically supported him, or the Irish who did not, his relationship with individuals of different ethnicities, as well as their groups, was as inconsistent as the man himself.

In 1858, in Bloomington, Illinois, Lincoln made one of his few remarks about the peoples of Asia, the nonwhite group with whom he had the least acquaintance and the least opportunity to think about. For one who had never been to Asia, or arguably for that matter, barely out of the United States, Lincoln prejudicially claimed that intellectual curiosity and scientific progress was the exclusive domain of the Western world. He recognized Asia as the birthplace of “the human family,” and concluded that Asians and Latin Americans, like African Americans, were indeed human beings, but he believed that Asia was an ancient, crumbling civilization whose time had long since passed and Latin America was an inferior land whose time had never come.

While neither respecting nor appreciating the cultures of Asia or of Latin America, Lincoln, like many nineteenth century nationalists, pandered to his audiences by emphasizing the attributes and virtues of the United States. At the expense of degrading other peoples, it was his intention to convince his fellow countrymen that their nation would be next on “the great stage of history,” a most successful strategy to flatter voters during his ascent into national prominence.

When the Republican Party was formed in 1854, the newly created anti-immigrant Know Nothings drifted into the new party and wanted Republicans to adopt an anti-immigrant stand. Lincoln refused. When he ran for president, he opposed any change in the naturalization laws or any state legislation by which the rights of citizenship that had previously been accorded to immigrants from foreign lands would be abridged or impaired. He advocated that a full and efficient protection of the rights of all classes of citizens, whether native or naturalized, both at home and abroad, be guaranteed.

Lincoln possessed sympathy for “the many poor” as he called them since he, himself, had long been one. One such manifestation of his broad view of how best to serve the interests of “the many poor” was his attitude toward immigrants. He never shared the nativist leanings of the old Whigs. Certainly his attitude had a political ingredient to it, but it was also made up much more of future hopes than contemporary realities. Much more crucial were his central economic beliefs. On the one hand he bade “God speed” to the immigrants if they could improve their lot by leaving their homes and coming to America; on the other hand he identified, correctly for his time and place, the growth of population, native and foreign-born, with economic development. Lincoln saw immigrants as important, the most important, of any country’s “natural resources.”

The Civil War not only diverted thousands of Americans from civilian to military pursuits, it also drastically reduced immigration. At first the Lincoln administration tried to meet the difficulty through unofficial State Department efforts, and by aiding the work of state agents, with the president taking an active interest in the matter. But, by the end of 1863, Lincoln decided to do more and directly asked Congress for assistance. His Annual Message to Congress that year requested that they devise a system for encouraging immigration. It spoke of the flow of immigrants from the Old World as a “source of national wealth,” and it pointed to the labor shortage in both agriculture and industry and to the “tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupation” who desired to come to America but needed assistance to do so. The conclusion showed that in spite of slavery and the war, Lincoln could still be a perceptive observer of the American need for immigrant labor. Congress responded favorably to the presidential request by passing the first, last, and only law in American history to encourage immigration, appropriately dated July 4, 1864.

With the exception of a brief trip to Niagara Falls, Abraham Lincoln never left the United States. And yet no one would deny that today he is a global figure, arguably larger than life both within and without the United States, especially including the many countries of Latin America. During his lifetime, however, he met very few Mexicans, a nonwhite group with whom he had little acquaintance but about whom he had many opportunities to think. His relationship with Mexicans began quite inauspiciously, if not downright unpleasantly, before he altered his opinions and before his legacy became time honored.

During his one term as a Congressman, Lincoln’s public opposition to the United States-Mexican War represented one of the few times he publicly took on the government’s policies toward Hispanics and Latin America. As a Whig member of the Illinois delegation to the House of Representatives, he introduced in December 1847 a series of resolutions, known as the “Spot Resolutions,” denouncing President James K. Polk’s handling of the war. In his resolutions, freshman Congressman Lincoln analyzed Polk’s messages seeking war with Mexico that claimed American blood had been shed on American soil. The House of Representatives, Lincoln declared, was “desirous to obtain a full knowledge of all the facts which go to establish whether the particular spot on which the blood of our citizens was so shed or was not at that time our own soil.” Soon into the new year of 1848, Lincoln delivered a meticulously argued speech in Congress exposing what he saw as the vagueness of jurisdiction along the Texas-Mexico border. Both countries, he felt, had a legitimate claim to ownership, thus rendering Polk’s declaration of war unconstitutional and contrary to international law. Lincoln apparently had high hopes for this speech, but was soon disappointed when the Democrats ignored his remarks and his fellow Whigs gave him only weak support. Lincoln’s opposition rested upon the contention that Polk’s handling of the crisis that precipitated the war represented a usurpation of war-making powers that the Constitution left exclusively to Congress.

Nevertheless, like most westerners, Lincoln had a low opinion of Latin American civilization and his references to Latinos were never flattering. In his debate with Stephen Douglas at Galesburg, Illinois, Lincoln attacked the concept of popular sovereignty—Douglas’ notion that the people of a territory should decide the slavery issue for themselves—by asking a hypothetical question as to whether Douglas would apply the doctrine in an acquisition like Mexico where the inhabitants were “nonwhite.” “When we shall get Mexico,” Lincoln asserted, “I don’t know whether the Judge [Douglas] will be in favor of the Mexican people that we get with it settling that question for themselves and all others; because we know the Judge has a great horror for mongrels, and I understand that the people of Mexico are most decidedly a race of mongrels.” Lincoln continued by claiming that “I understand that there is not more than one person there out of eight who is pure white, and I suppose from the Judge’s previous declaration that when we get Mexico or any considerable portion of it, that he will be in favor of these mongrels settling the question, which would bring him somewhat into collision with his horror of an inferior race.”

Even if allowance is made for the fact that these comments by Lincoln occurred in an intense debate where serious race baiting was occurring, He still used derogatory comments about Hispanics in speeches where there was no apparent motive. In describing the Cubans, Lincoln pulled no punches. “Their butchery was, as it seemed to me,” Lincoln said in 1852, “most unnecessary and inhuman. They were fighting against one of the worst governments in the world [the Spanish]; but their fault was, that the real people of Cuba had not asked for their assistance; were neither desirous of, nor fit for, civil liberty.” Later in a patriotic speech extoling the innovation and brilliance of “Young America” with the “Old Fogy” countries, crediting Americans’ technological success to their intellectual powers of observation and experiment, Lincoln chided, “But for the difference in habit of observation, why did Yankees, almost instantly, discover gold in California, which had been trodden upon, and over-looked by Indians and Mexican greasers, for centuries?”

Lincoln, generally speaking, was pessimistic about the possibility of white people accepting nonwhites as equals. Often he spoke in flattering praise of white Americans’ technological and moral superiority while denigrating peoples of color, peoples with whom he had little actual contact. But Lincoln was a private person by nature and a political person by appearance. Thus, how much of this represents the inner heart and mind of Lincoln may be a different matter.

Assuming, however, that his public record reflects his private sentiments, Lincoln believed the nations of Latin America to be backward. Perhaps his residence played a part in his closed-mindedness toward Hispanics. His Springfield neighborhood, while diverse with many German, Irish, Portuguese, Scottish, and French immigrants, included virtually no Mexicans. Indeed, his lack of first-hand knowledge of Mexicans would remain that way until a fateful day in January 1861 as President-elect Lincoln prepared to embark on his journey to become the nation’s sixteenth president.

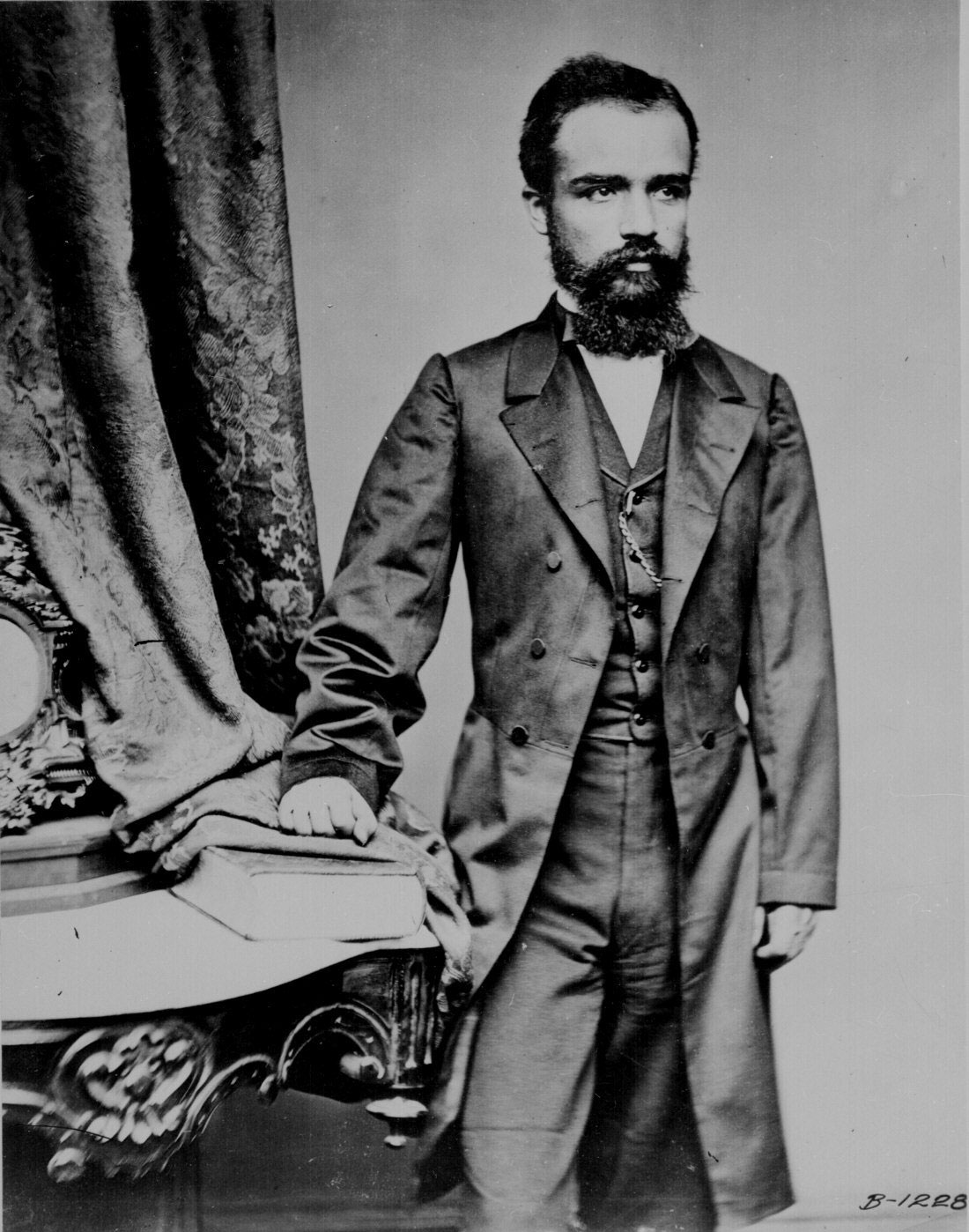

“It is the wish of the President that you proceed to the place of residence of President-elect Lincoln and in the name of this government, make clear to him in an open manner, if the opportunity offers, the desire which animates President Juarez, of entering in to the most cordial relations with that government.” With those words, twenty-four year old Matias Romero, in charge of the Mexican Legation in Washington, set out for Springfield, Illinois, on January 7, 1861, to meet, congratulate, and cajole the newly elected Abraham Lincoln. Romero’s visit would begin an unlikely friendship with Lincoln that would enhance both their lives.

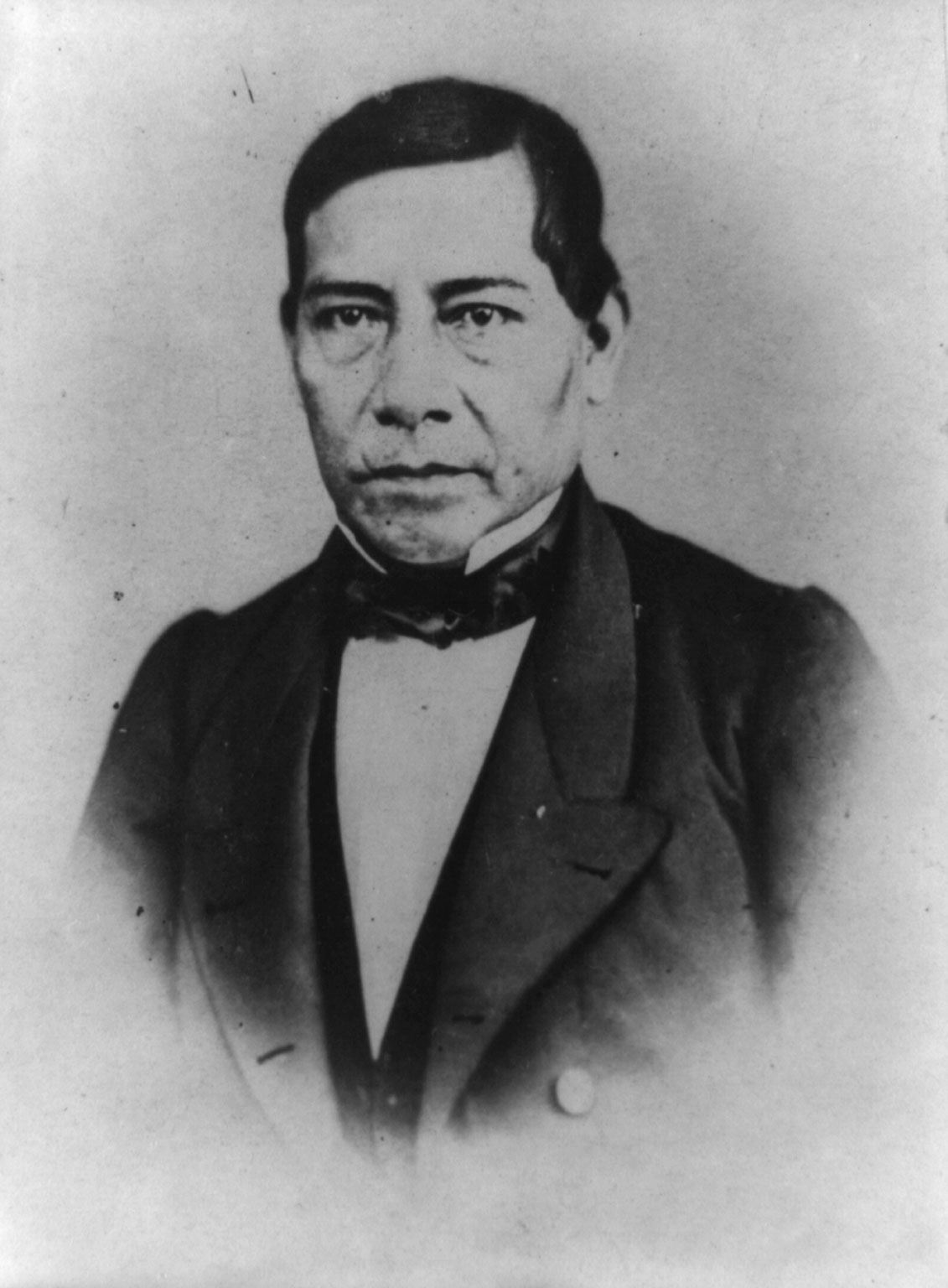

Romero began his visit by providing Lincoln with a thorough briefing on the situation that existed in Mexico. The new Mexican president, Benito Juarez, had assumed leadership of a country that was not only devastated by civil strife, but one whose treasury was seriously depleted by the depredations of Santa Anna and the Reform War. It was believed by both Romero and Mexican leaders that Lincoln was predisposed toward friendship, as his Congressional record was well known and his political embarrassment caused by opposing the Polk administration’s desire for war with Mexico was well documented.

Romero’s visit to Lincoln was an especially significant and unique visit. By many accounts, this was the first time Lincoln conversed directly with a person of Mexican descent. Furthermore, though he was about to assume responsibility for American foreign policy, Lincoln had received not a single caller from the capitals of Europe between his election and inauguration. Lincoln’s personal secretary, John Hay, was understandably gratified to observe Romero’s display of “deep respect and consideration” for the president-elect. Indeed, Lincoln was taken with the young diplomat from the outset.

In contrast to the turbulent relationship between the United States and Mexico in the first half of the nineteenth century, Mexico genuinely looked forward to a Lincoln presidency. In fact, Romero, in his voluminous notes, diary, and correspondence was the first to note the similarities in personality, demeanor, intelligence and background between Lincoln and Mexican leader Benito Juarez. Indeed, shortly after Lincoln’s election, Mexico had emerged from its own civil war. Mexico’s new leadership wanted nothing more than economic cooperation with the United States and to be treated as a respected southern neighbor; something that would not have even been considered with Lincoln’s pro-southern Democratic predecessors who were bent on the annexation of significant portions of the Mexican nation. Now, with the election of Lincoln’s Republicans on a platform of free-soil and free-labor, Mexico’s new leadership counted on the Lincoln administration to respect Mexican territorial borders.

Sensing Lincoln was not well-informed about the situation in Mexico, Romero explained fully the objects of the party of reform. “I told President Lincoln,” Romero wrote in his report to the Minister of the Exterior, “that the constitutional government desires to maintain the most intimate and friendly relations with the United States, to whose citizens it proposes to dispense complete protection and to concede every form of facilities toward developing commercial and other interests of both republics. Mexico wants to adopt the same principles of liberty and progress followed here,” Romero continued, “[and Lincoln’s] administration with regard to Mexico is expected to be truly fraternal and not guided by the egotistic and antihumanitarian principles which the Democratic administrations had pursued in respect to Mexico, principles that resulted in pillaging the Mexican Republic of its territory in order to extend slavery.”

Ever the lawyer, Lincoln questioned his visitor very closely on the conditions in his country and was especially interested in the status of the peons, a group which Lincoln feared, lived in a state worse than that of the slaves on southern plantations. He pressed Romero on whether the abuses of the Indians working in the hacienda systems were “general and widespread in the Republic and [were] authorized by law.” Lincoln was also concerned whether the conditions of the hacienda system were exaggerated by the press in the United States as he had read some very troubling descriptions of mistreatment there. “I explained in detail how such abuses were committed,” Romero wrote, “[and] he expressed great satisfaction in learning that such practices were contrary to the laws of the Republic and that, when Mexico has a solidly established government, it will attempt to correct these abuses.”

As he had done with his two young secretaries, John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Lincoln took almost a fatherly posture with Romero. Lincoln found Romero to be intense, yet quite polished in manners and charming in demeanor. While it is likely that Romero did not understand all of Lincoln’s downhome stories and yarns, the young diplomat was apparently amused by Lincoln’s frequent laughing at his own stories. When their initial visit ended, with old-worldly courtesy, Romero vowed “to return to see Lincoln again to take leave of him”.

Romero was true to his word. Two days later he returned to Lincoln’s home to bid him farewell. This time it was a less intimate setting because there were a number of other visitors there and Lincoln was very preoccupied. Nevertheless, Lincoln made it a point when he was able to introduce Romero to the others there as his new friend from Mexico, a gesture most appreciated by Romero. In Romero’s opinion, the two visits with Lincoln had been rewarding and would prove crucial in advancing the interests of Mexico. Even though Romero had concluded that Lincoln was not particularly well informed about the situation in Mexico, he was impressed that the president-elect was a receptive listener who asked probing and significant questions. Romero was confident that Lincoln’s administration would be friendly, as the sentiments which Lincoln had expressed came from a man whom he judged to be a “sensible, honorable man, and his words carried the stamp of sincerity and not of pompous phrases, empty of meaning, which, when used by the people educated in the school of false politics, have the habit of offering much and giving little.”

Soon both Lincoln and Romero were in the nation’s capital and their friendship was renewed among the darkening clouds of war in the United States. Lincoln once again found Romero to be particularly gracious and personable. As he had quickly done in Springfield, Lincoln treated Romero as “one of his boys,” a truly remarkable development given that Lincoln, as a westerner, had once spoken so disparagingly about the Mexican people. Perhaps even more significant, however, the Lincoln family befriended Romero. Mary Todd Lincoln, the difficult and mercurial soon-to-be First Lady felt the same way about Romero as her husband. What particularly endeared Romero to the President was gratitude; Romero, with good-natured grace, frequently escorted Mrs. Lincoln on her many shopping trips to the Washington fashion stores.

Doubtless it was a duty which Lincoln was extremely happy to relinquish. But Mrs. Lincoln also had many conversations with Romero during which she shared his anxiety over France having an army in Mexico and the danger of it allying with the Confederacy. Based on their mutual concerns, she frequently urged President Lincoln to support Mexico. Then, too, when Romero had the funds he hosted dinner parties and other social events at the Mexican embassy and frequently invited the Lincoln’s oldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln. After accepting one such invitation Robert jokingly wrote to Romero, “I hope I may be able to come off unscathed by your double attractions—ladies and the table.” Romero had indeed become almost a part of the extended Lincoln family.

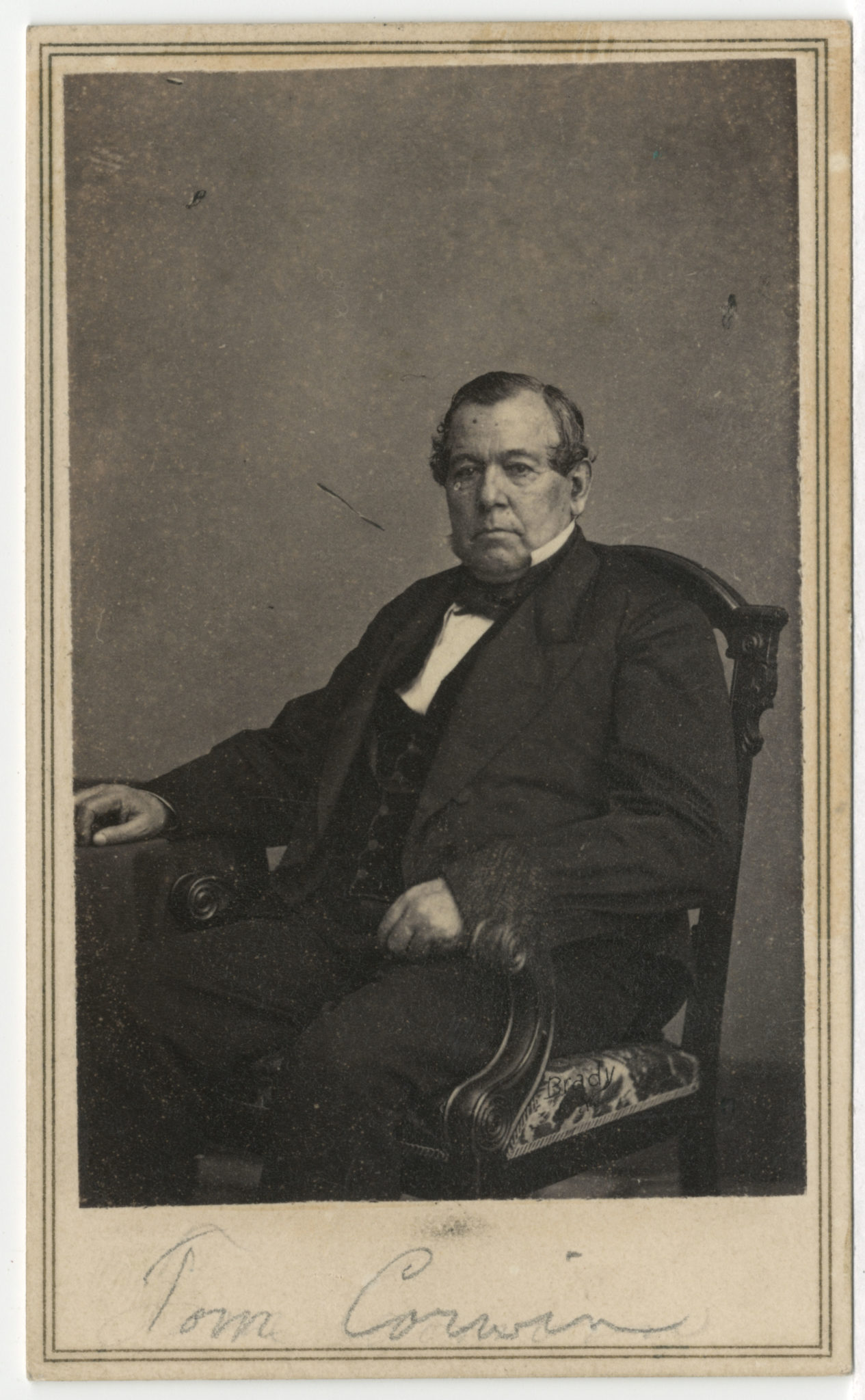

By early February, the president-elect informed Romero that he was deeply troubled about reports of a French-led operation in Mexico. Lincoln told Romero that he would treat Mexico “with sentiments of the highest consideration and of true sympathy,” and he kept his word. As President, Lincoln made the immediate appointment of former United States Senator Thomas Corwin, the renowned orator and vocal opponent of the Mexican-American War, as ambassador to Mexico. Lincoln also approved the terms of a loan to Mexico that Corwin recommended, the first ever proposed to a foreign nation, but one that Congress eventually rejected.

Union loyalists feared that the French operation might be a prelude to full-scale intervention in the Civil War. The Lincoln administration indirectly invoked the Monroe Doctrine whenever they could to prevent French maneuvering in Mexico from becoming “a pretext for getting into the American waters a large force, ready to act in liberating cotton when the time comes.”

Romero reinforced Lincoln’s views on hemispheric independence. Visiting Lincoln in the White House, Romero declared that the principles of the Monroe Doctrine “seem to be written for the present occasion.” As consumed as Lincoln was with the Civil War, because of his affection for Romero, and much to the chagrin of the long line waiting to see him, he took the time to sit down and listen to the young man. Lincoln listened “with marked attention and without interrupting” Romero. When he did speak Lincoln told his friend that he and his Cabinet were “deeply aware of the importance and significance of the matter. . . .They had dedicated their fullest attention to this . . . occupying themselves with it in preference to all other important problems.” Lincoln made clear that his purpose “was to try to prevent the armed intervention of France and England in Mexico, or failing in that, to defer it as long as possible.” But with the war going poorly for the North, Lincoln was able to offer no practical proposal for accomplishing that. An American invasion of Mexico was out of the question.

In the coming months Romero visited Lincoln more often, both personally and in his position as Mexican Charge d’Affaires. No visit was more poignant than after Lincoln lost his eleven year old son Willie to typhoid fever in February 1862. Both parents were devastated and the president did not return to work for three weeks. When he did return to work, Lincoln again met with Romero, but had little good news to share with him. The war remained perilous for the North and each defeat made Lincoln, who was already emotionally weakened from mourning his son, more disconsolate.

In Mexico, meanwhile, Napoleon’s forces were finally making their own progress. In June 1863, French troops broke through the remaining Mexican defenses and poured into Mexico City. For Lincoln, the French occupation of Mexico City could not have come at a worse time. Lee’s Confederate forces were inching closer to the Federal capital and Lincoln was growing more despondent daily according to most around him, looking “exhausted, care-worn, spiritless, and extinct.” Romero visited the White House during this time and agreed with that description. Lincoln had “drooping eyelids, looking almost swollen; dark bags beneath his eyes; deep marks about the large and expressive mouth; and flaccid muscles of his jaws.” Indeed, even with his own homeland in civil turmoil, Romero feared for Lincoln’s health and well-being.

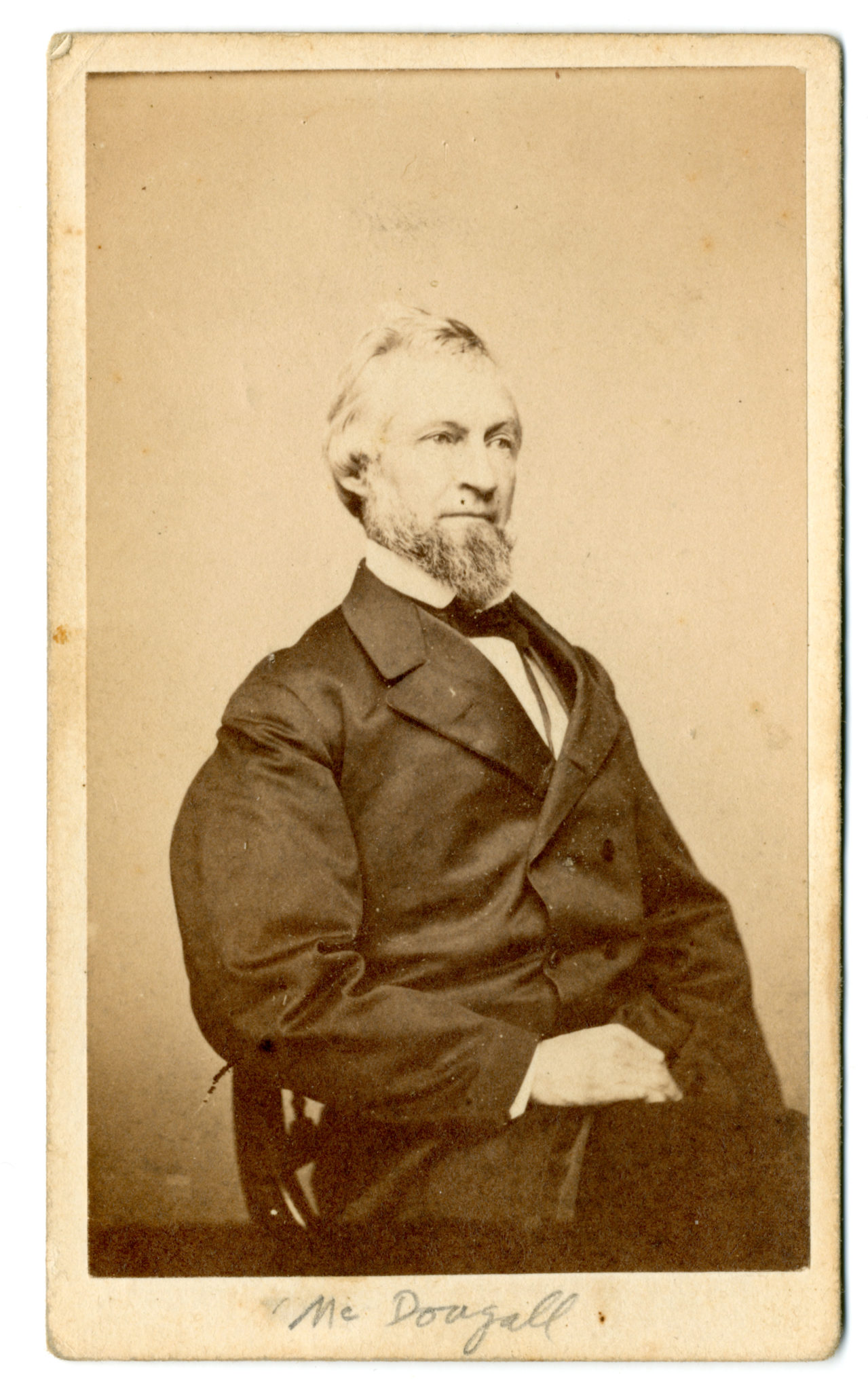

Nevertheless, Lincoln’s reluctance to intervene in Mexico while he was fighting a Civil War at home began to frustrate Romero, who by 1864 grew increasingly impatient with his friend of four years. The president and his Secretary of State, William Seward, held a firm line against the war hawks in Congress, the State Department, and elsewhere. They were supported by prominent Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner who wrote hawkish California Senator James A. McDougall, “Sir, have we not war enough already on our hands, without needlessly and wantonly provoking another?” Sumner managed to kill McDougall’s resolution calling for Napoleon’s expulsion from Mexico, “and that failing this, . . . ‘it will become the duty of the Congress of the United States of America to declare war against the government of France,’” complaining that there was “madness in the proposition.” With it becoming painfully apparent to Romero that Lincoln was not going to take on Napoleon, the Mexican envoy complained to his superiors that “[Lincoln’s and Sumner’s] fear of France makes [them] as condescending with that nation as Seward.”

Romero’s friendship with Lincoln would be put to the test during the late summer of 1864. With many observers, including Lincoln himself, believing that he had little chance of reelection, his erstwhile friends and admirers began to turn against him. Romero, out of frustration with Lincoln’s inactivity on the Mexican crisis, met with James McDougall who had been aggressively advocating all summer in the Senate for a harder line on Mexico. McDougall told Romero that the president’s reelection would be a “calamity” for Mexico and it was “necessary to avoid this very deplorable prospect at any price.” Once friends with the president, McDougall now complained to Romero about Lincoln’s “very objectionable conduct of United States foreign affairs, most especially in regard to Mexico.” Romero, torn between his warm friendship with Lincoln and his determination to rid his homeland of its invaders, found himself now eager for a new American administration that might forcefully challenge Maximilian’s regime. In a moment of haste he would regret, Romero agreed to help McDougall compile opposition research in a dossier that would enable McDougall and the Congressional Mexico hawks to “vigorously attack the government on the subject. . . . [and] prevent Lincoln’s reelection [by] directing all their effort to this task.”

Stories of Lincoln’s electoral demise were premature, however, and the president, aided by significant and timely military victories by General William T. Sherman, easily secured a second term. Sadly, Romero did not have the time or opportunity to make amends with his old friend. Within five months of his reelection, and less than a week after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, Lincoln was dead.

Only after Lincoln’s death, did Romero see that despite being consumed by Civil War, Lincoln had not completely neglected his friend’s requests. Speaking with Ulysses Grant during one of the memorial services, Romero learned from the general that, as one of his last acts, Lincoln signed “an exequatur recognizing Jose A. Gody as Mexican Consul in San Francisco.” Indeed, with the war finally winding down the president appeared to be moving in the direction that Romero had desired all along. Grant told him that although he and Lincoln were “tired of war, his major desire is to fight in Mexico against the French, that the Monroe Doctrine has to be defended at any price, and that the French ought to leave Mexico before the United States demands it imperatively.” Grant believed that Lincoln was moving toward that opinion and planned on acting in this regard before his life was cut short by an assassin’s bullet at Ford’s Theatre.

Lincoln’s inability to intervene openly in favor of the Juarez government did not prevent him, however, from ignoring the abundance of arms smuggled across the Mexican border. After Lincoln’s death, some 3,000 Americans, mostly Union veterans, joined the effort of Mexicans who were trying to overthrow the French-imposed empire. One group of volunteers for Juarez, called the American Legion of Honor, was organized as an elite military company. Its more than 100 officers were commissioned by President Juarez, and legionnaires fought in the final battles leading to the downfall of Maximilian and his empire.

Romero would live forty-three years after his friend’s death and would continue to lobby for Mexico with several of Lincoln’s successors. However, he would never again form the almost father-son relationship that he had developed with Lincoln. In some letters to superiors in Mexico Romero described Lincoln as “immortal,” and, as Romero aged and the world became an even more complicated place, he fondly reminisced about being treated so kindly by Abraham Lincoln, a man as complicated as he was kind.

Jason Silverman is Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History Emeritus at Winthrop University.