The Debate over the Debates: Debating Those Debates: The Historians Weigh In

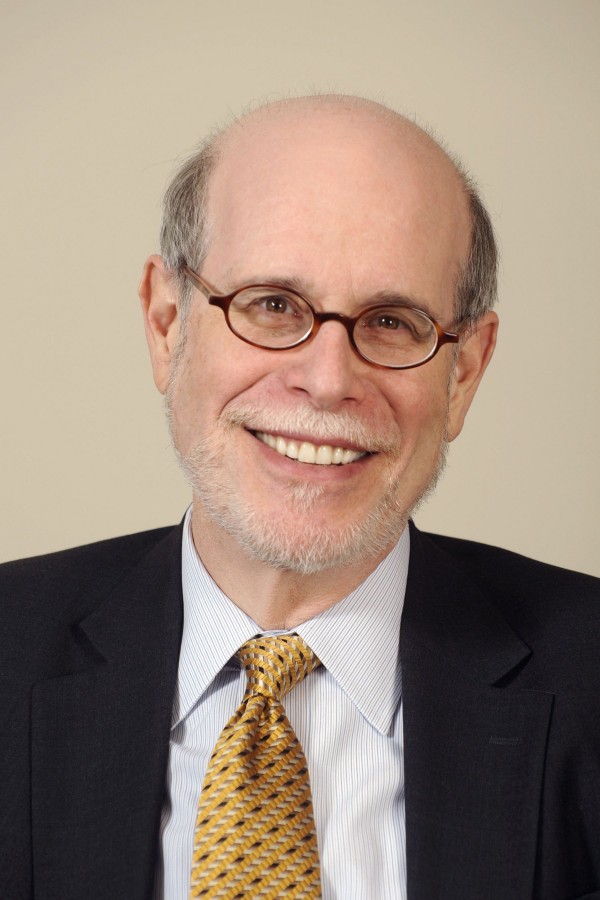

Moderated by Harold Holzer

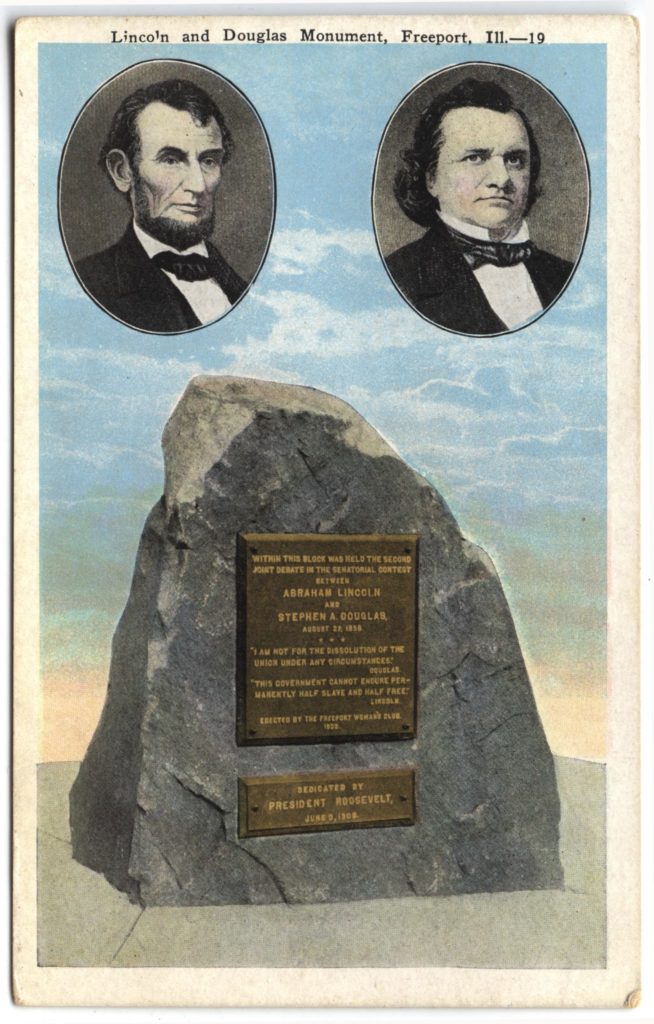

A public sensation in the seven Illinois towns that hosted them—reprinted in the press at the time, in book form shortly thereafter, and in many editions since—the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates are remembered today, 160 years after they took place, as a political and cultural phenomenon.

But as much as they attracted attention then and since, they now invite a debate of their own: What did these famous meetings really accomplish? What is their legacy? Did they make history, alter history, or truly represent the apogee of 19th-century political discourse? Or, in fact, have they been overrated, both as political theater, historical impact, and rhetorical accomplishment?

Although I edited a 1993 volume of debate transcripts, I remain on the fence myself—unsure of precisely how much sustained reverence the encounters deserve. To assess the debates in current historiography, I asked three friends, all major historians, to weigh in:

Frank J. Williams of the Lincoln Forum, author of Judging Lincoln

Edna Greene Medford of Howard University, author of Lincoln and Emancipation

Douglas L. Wilson, Director of the Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College (located on the site of the fifth Lincoln-Douglas debate at Galesburg, IL)

Here is how they responded to my questions (and how, in brief, I feel about these issues as well):

Are the Lincoln-Douglas debates greater in reputation than in text or actual, period political impact? If so, why?

FJW: In a sense they are. The debates became the “grand-sire” of future debates, but it took almost a century before they became the inspiration for future political debates. Beginning as a statewide contest for the U.S. Senate, they became the standard in 1960 in the presidential debates between Richard M. Nixon and John F. Kennedy. In between 1858 and 1960, custom forbade new debates. As with Lincoln-Douglas, the 1960 debates were expected to inspire with the candidates’ words, despite the restrictions of television.

DLW: There is no doubt that the debates are “greater in reputation than in text,” because most modern readers, while honoring their reputations, are all-too-typically put off by reading the debates themselves. And for good reasons. They quickly discover that the issues being discussed are clothed in the dress of arcane 19th-century politics, such as the English bill, the Crittenden-Montgomery bill, the Lecompton Constitution, and the Northwest Ordinance. How are they supposed to fathom why these leading politicians are still arguing about the writing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, let alone the execution and effect of it? How can they judge between Douglas’ and Lincoln’s readings of the Dred Scott decision if they hardly know what Dred Scott was? These are the kinds of questions that cause so many modern readers who approach the debates with real anticipation to retreat with something like buyer’s remorse.

EGM: To some extent, we have romanticized the debates, casting them as the model for political contestations. Despite following the rather common practices of 19th-century debates— charges and counter-charges, accusations and refutations, half-truths and mis-characterizations (practices just as prevalent today)—they continue to generate interest primarily because of Lincoln’s involvement and doubtless because of the improbable long-term impact they had on the national discourse over slavery. Who could have foreseen in 1858 that, just two years later, the defeated candidate would receive his party’s nomination and eventually be elevated to the presidency, or that this would lead to southern secession, civil war and the abolition of slavery? But beyond this “reputation” for greatness, the debates are deservedly so because of the effort of both debaters to help average Americans make sense of the thorniest issue of their day. It is hard to over-emphasize the significance of those discussions for their time and ours.

HH: All good points—and I suspect even the Hayne-Webster debate of blessed memory would not wear well for modern readers. What the Lincoln-Douglas texts cannot capture is the roiling excitement they generated. As one Eastern newspaper marveled, they set the prairies “on fire.”

What accounts for their high reputation as the apogee of political debating (among later leaders as diverse as Admiral Stockdale and Mario Cuomo)?

EGM: Admirers of various persuasions consider the debates political dialogue in its purest form. There was no press or moderator asking questions, just the two candidates, each in turn standing before an audience of fellow citizens, delivering their arguments and rebutting charges leveled by their opponent. They did this even in the heat of the summer, outdoors, and without amplification, in front of thousands of spectators over a three-hour period. And somehow they managed to keep the attention of the audiences. They remained poised while enduring unruly crowds and even answered questions that were shouted to them by the unconvinced and impatient. Understandably, politicians ever since have praised the aplomb with which they pressed their agenda under less than ideal circumstances.

FJW: Political leaders like Governor Mario Cuomo, a great orator in our age, personified the eloquence of an era in which leaders inspire with their words.

DLW: There are at least two possible explanations. The first is that such fans belong to the category of committed readers who are willing to take the trouble to understand the kinds of unfamiliar matters cited above, and admire the way Lincoln stood his ground on important issues that were not yet supported by the majority but would eventually prevail. Another possible explanation is that they are simply willing to accept that these by-now murky discussions were important enough at the time to have produced the acknowledged outcome, which was to help lay the groundwork for a prairie politician like Abraham Lincoln to rise to and successfully compete at the national level.

HH: I could never convince Mario Cuomo that the Lincoln-Douglas debates amounted to less than their reputation. The more important idea, he argued, was that each candidate was allowed to speak for 90 minutes. He felt passionately that short-form modern debates cheated debaters and listeners alike, and represent no real test of knowledge, ideas, or stamina.

Both Lincoln and Douglas said things during the debates that sound racist today—indeed were in many minds racist then. Where did Lincoln and Douglas fit into the spectrum of racial thought (among white voters and leaders) of the era?

FJW: Both Lincoln and Douglas were “racist”—except Lincoln alone sought the end of an institution that violated the promises of equality contained in the Declaration of Independence. Douglas was content to keep the status quo ante. Political to their core, the debates also had a moral dimension on the issue of slavery. Neither candidate discussed other issues of national importance like tariffs, internal improvements, immigration, or homesteading. Both men were fighting for the undecided votes from central Illinois. The majority of the state’s southern voters was sympathetic to slavery and would support Douglas while the anti-slavery men in the northern counties would go for Lincoln. So, the election would depend on the undecideds. But Lincoln did pander to southern voters as he expressed racial sentiments in the fourth joint debate at Charleston in the southern part of the state. Lincoln was on the defensive with Douglas’s charge that the Republican candidate was an abolitionist. To counter that, Lincoln stated that he was not in favor of equal rights for blacks. After Charleston, Lincoln tried to avoid making statements about equal rights, concluding he had gone too far there. Nonetheless, those comments effected his reputation then and now.

EGM: It is interesting that we often treat Douglas’s racialized words as prima facie evidence of his own bigoted beliefs. Indeed, he left enough proof for his critics to tag him with the “racist” badge without fear of seeming overly disparaging. But we are somewhat reticent when it comes to Lincoln’s racial “insensitivities,” choosing instead to soften the sting of his words by citing the bigotry of the audience he faced or the necessity to counter Douglas’s race baiting, especially in places such as Charleston. The truth is that both men were products of their times. Most 19th-century white men and women thought of black people as innately inferior, and often failed to see the actual and potential abilities of those who had survived the oppression of American slavery and racism. Even abolitionists (with the exception of an enlightened few) shared that view of people of color. Lincoln, however, separated himself from Douglas (and from the majority of white Americans) in his ability to see beyond his racial prejudices when it came to championing the right of all men and women to the freedoms espoused in the Declaration of Independence. That did not mean social or political equality (certainly not in 1858), and did not embrace the freedom to which people of color aspired, but it was a decidedly more enlightened perspective than most.

DLW: To take the debates seriously, it is necessary to come to grips with the racial prejudices and ugly stereotypes that then prevailed. Especially for American readers in the 21st Century, who more and more have come to accept the substance of Lincoln’s belief that the Declaration of Independence’s assertion of equality includes people of color, it is instructive to understand that this was far from the case in Lincoln’s day. That Douglas could scorn Lincoln’s position on racial equality, that he could boldly claim that blacks were inherently inferior to whites, that Lincoln would at the same time strongly deny Douglas’s charge that he was an “abolitionist,” require historical perspective. Douglas took the position he did because it was popular, representing the attitude of the overwhelming majority of voters, whereas Lincoln’s position was only beginning to gain a following. While Lincoln was genuinely anti-slavery, he tried to make it clear that he was not an abolitionist, that is, someone who advocated an immediate end to slavery and full rights for freed people. Racial discrimination was almost universal in Illinois, and no one could possibly be elected to statewide office on such a platform. Douglas, in standard political mode, relentlessly insisted that despite Lincoln’s denials, he was indeed an abolitionist, and that his party’s political aim was to surreptitiously “abolitionize” unsuspecting citizens. The truth was that Lincoln’s recently founded political party was a work in progress and, except for being against slavery its members were having trouble finding common ground on other issues.

HH: These are insightful observations. I would add only that the transcripts of the Charleston debate show that when Lincoln launched into his argument that people of color were in fact not entitled to civil rights, he began by alluding to the fact that it had been previously whispered that he favored racial equality. That comment actually elicited laughter from the crowd. Not very nice, to be sure, but an indication that few white voters could believe a mainstream politician might harbor such “radical” views. Had Lincoln been more advanced in his thinking in 1858, he wouldn’t have been a Senate candidate—or debater—in the first place.

Describe, in brief, the position of each candidate on slavery and equality—if not in all things, then in equality of opportunity? Compare the candidates’ positions to the mainstream position among white voters in 1858 Illinois?

DLW: Much of the early opposition to slavery was religious, but in his 1854 Peoria address, Lincoln had offered a secular argument based on the idea of self-government, which he described as “absolutely and eternally right.” As he put it: “When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism.” This put the onus directly on the slaveholders and other defenders of slavery, and would help provoke what historian Harry K. Jaffa called the “Crisis in the House Divided.” If democracy consists in following the will of the majority, what measures can be taken when the majority is perceived as morally in the wrong? This was the task that Lincoln and other founders of the Republican Party faced in the period in which the debates occurred.

FJW: By the time of the debates, Illinois voters knew the positions of both candidates. They had been debating contrary views ever since Douglas engineered the Kansas-Nebraska Act reversing the 1820 Missouri Compromise. This opened territories to slavery in areas acquired from the Louisiana Purchase and the war with Mexico. Douglas advocated “popular sovereignty,” which permitted white citizens in every new state the right to vote slavery up or down, arguing that it was a right of self-government. Lincoln, derisively, labeled this policy “squatter sovereignty,” in which a small number of slaveholders could enter a new territory and, by using a manipulated majority for slavery, establish the institution for a larger number of settlers who would arrive later. Lincoln always contended that slavery was wrong and should not be extended—especially by a few who would bind later generations. Lincoln also thought the Founders had planned for the ultimate extinction of slavery. Both battled over the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln believed that the inalienable rights guaranteed therein were designed for every living person whether white or black—at least insofar as the opportunity to rise. Douglas believed that America “was established on the white basis…for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever.”

EGM: As a proponent of Popular Sovereignty, Douglas embraced the idea that African Americans were inferior and not a part of the body politic. Lincoln believed that the nation’s founders recognized the contradiction in their espousal of freedom for all while tolerating the enslavement of a significant segment of the population. Hence, while they compromised on the issue of slavery in order to win over the proponents of the institution, they had placed it on a path of natural extinction. And while Lincoln did not believe African Americans were equal to whites socially or were capable of responsible participation in government, he famously declared that they had a right to enjoyment of the rewards of their labor, and he championed the idea of equality of opportunity. While this fell far short of a complete equality, it exceeded the desires of the majority of Illinoisans, where discriminatory laws still kept black people subordinate.

Do we know—or can we imagine— what each candidate was like as an orator and debater?

EGM: As the incumbent and a well-known politician, Douglas had the advantage of experience on both the statewide and national levels. One would expect his delivery to be sophisticated but also tailored to the audiences he sought to persuade. He excelled at both. Although short in stature, his commanding voice and charismatic presence kept the crowds engaged. Lincoln exhibited a different kind of presence. Although taller than Douglas by almost a foot, his gangly frame, plain face, and ill-fitting clothes suggested to some that he was not worthy to be on the same stage with the very polished Douglas. Moreover, his high-pitched voice must have been jarring to the audiences before whom he and Douglas spoke. Yet Lincoln was clever enough to use these seeming disadvantages to his benefit. His unpretentious demeanor, coupled with his passionate defense of his position and his vast understanding of the issues, captivated the audiences and won the respect of those who saw in him a man who shared their concerns about the nation’s future. Of course, both men used humor to entertain and keep the crowds engaged. Both understood the power of levity, and used it to great advantage.

FJW: Lincoln was probably the most eloquent orator of the time if speaking from a prepared text. But he, unlike Douglas, was a failure as an impromptu speaker—despite his talents as an artful storyteller and trial lawyer. Yet a review of the debate transcripts reveals Lincoln could be organized and deliver a smooth, hour-long speech and 90-minute rebuttal or 30-minute rejoinder. Douglas was a bully and displayed his tendency for relentless attacks against Lincoln despite Lincoln’s droll humor. It appears from the record that Douglas, and not Lincoln, was the more cogent and impressive extemporaneous speaker. But it is difficult to judge because one cannot determine a speaker’s skill and spirit from printed transcripts alone.

DLW: The two candidates’ oratorical and debating styles would appear as different as their distinctive physiques. The short and stocky Douglas had an aggressive style and personality, and this gave shape to his character as a debater. He was equally at home with anecdotes and assertions that were true as those that were partly true or even patently false. He had enormous self-confidence and a slashing style when on the attack. While not given to eloquence, he was a smooth and articulate talker, always ready with a quick comeback or for whatever the occasion required. He seems to have had a deep baritone voice of great authority, which could be heard over large and noisy crowds. Lincoln, as is well known, was a very different physical type from Douglas, and just as different as a speaker, although he, too, had a voice that could be heard by large crowds, though in a much higher register than Douglas’. Lincoln’s gifts as an orator are harder to characterize. He spoke with more deliberation than Douglas, always careful to qualify and refine his assertions, where Douglas was quite willing to go over the top now and then. Where Douglas was openly self-regarding and boastful, Lincoln tended to take the opposite tack, playing down his abilities and spoofing his own position and appearance. Douglas was, at this time, perhaps the most famous and commanding political figure in the country, and Lincoln’s strategy was always to acknowledge him as the larger figure. Of course, he knew how to use this ploy to his own advantage. Especially in these debates, it is Douglas who tries to lay down the terms of the debate, and Lincoln who willingly plays the role of the challenger.

HH: Would either style work today? I doubt it—but I know I speak for my colleagues in wishing there were some way we could go back in time, at least for three hours, to watch them in person. It must have been mesmerizing.

How important was the stenographic recording of the debates and their reprinting in Illinois and some national newspapers? To the outcome? To the future?

DLW: There can be little doubt that the stenographic recording was consequential. At this period, the newspaper reporting of political speeches was still overwhelmingly partisan, so that the readers of a given paper expected to read that the speaker endorsed by newspaper’s party affiliation would get the best of his opponent, whose arguments and conduct would be shown in a very unfavorable light. Newspaper coverage of political speeches on a nearly verbatim basis only became possible with the rise of a skilled brand of short-hand reporting, and such was the importance and immense interest in the projected debates between Lincoln and Douglas that the leading Chicago newspaper for each party took on the responsibly of reporting the seven debates in their entirety. This made it possible for newspapers all over the country to follow these discussions in such detail as to present a clearer sense of the arguments and their proponents. Lincoln could be said to have gained disproportionately to Douglas, because he was relatively unknown beyond Illinois, whereas Douglas’ reputation was well established. Without the near-verbatim reporting of these debates, readers around the country would have had very little opportunity to see that Douglas’s little-known challenger could not only hold his own, but was a man to be reckoned with.

EGM: As evidence of the importance of Lincoln’s joint discussions with Douglas, two of the state’s newspapers hired stenographers to attend the events and record the arguments. Although these recordings were often biased, reflecting the partisanship of that time, they introduced a broad segment of the population to Lincoln, not an unknown quantity, but certainly far less familiar to statewide and national audiences than Douglas. While the better-known candidate won (through election by the legislature, not directly by voters), the newspapers revealed Lincoln as a worthy opponent who had a thorough command of the issue of slavery and its extension into the territories. He had spoken on this issue many times before, but the attention the debates received through press coverage doubtless elevated him much farther and faster than would have been the case otherwise.

FJW: These were the first great political contests recorded through “phonographic” reporting. This marked not only a milestone, along with the telegraph, which spread transcripts of the debates to the entire country, but the basis for the fame of the debates – then and now. The partisan press, namely the Chicago Press and Tribune supporting Lincoln and the pro-Douglas Chicago Times, contributed to the enduring reputation of the debates, as well as to the ultimate distortion each stenographer manifested in favoring their man. The impact of the printing of the debates is hard to measure but Lincoln carried the popular vote—if not the election.

HH: Lincoln would agree with my friends—Douglas, too, at least at the outset. It was Lincoln who had the foresight to collect the newspaper transcripts and see to their re-publication in book form. Douglas squealed like a stuck pig, furious at Lincoln (and perhaps himself) for losing control of the texts. One of my favorite side-stories of the debates, one about which I’ve written often, is the debate over whose transcripts were more accurate. In truth, neither was so.

Who won the Lincoln-Douglas debates—in 1858, in history, and in memory?

FJW: If debates are judged from the election results, Douglas. There was no direct election for U.S. Senators until 1913. In 1858, state legislatures chose the winner. It appears that Republicans received 125,000 votes to 121,000 for Democrats. Yet, Douglas prevailed over Lincoln men in the crucial contest for legislative seats: 41 went to Republicans and 46 to Democrats, including holdovers. But, arguably, Lincoln won the debates by engaging his nationally known rival and emerging as a national figure in his own right. He also inhibited the Republican Party’s flirtation with Douglas. Employing hindsight, historians and Lincoln students have found Lincoln’s views on race more progressive than Douglas’s. So, Lincoln won on moral grounds, too.

EGM: Since Douglas retained his Senate seat, one must conclude that he was the immediate winner. But in the long term, Douglas lost. His defense of the idea that territorial residents could decide to embrace or exclude slavery pleased neither the proponents of the institution nor those who wanted to limit it. To the extent that the debates drew even greater national attention to the divisive slavery issue, Lincoln and America won. While the debates represent a step farther along the path toward disunion, it helped to facilitate the climate that soon led to the destruction of the institution and the preservation of the Union under the banner of statutory freedom for all.

DLW: By almost any measure, Douglas won the debates, for he was duly elected in early 1859 by the legislature. But there was one thing in the offing that he lost and Lincoln won, and that was the presidential election of 1860. It appears in retrospect that Lincoln had begun angling for the chance to run in 1860 even before the active campaigning for Senator in 1858 had begun. The evidence for this can be found in his carefully calculated nomination speech in June 1858—the “House Divided” address—in which he predicted the federal “government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” His close political associate Leonard Swett spoke for many Republicans when he said later that “nothing could have been more unfortunate, or inappropriate; it was saying first the wrong thing, yet he saw it was an abstract truth, but standing by the speech would ultimately find him in the right place,” that is, with national visibility as a candidate for president. Most historians of these events would endorse the idea that Lincoln’s performance in his debates with Douglas was nonetheless indispensable to eventually being nominated for president. It is, of course, distinctly ironic that the nominal winner of the debates was ultimately the big loser, for not only did he lose out to Lincoln in 1860, but most of his ideas and political programs ended up on the wrong side of history.

HH: Would we be reaching this conclusion had the national Democratic Party remained intact in 1860 with not two but one presidential nominee—Douglas? Had he won the presidency that year, not Lincoln, we might be having an entirely different discussion today, in an entirely different nation. If the Lincoln-Douglas debates, however flawed, contributed to the great “national consummation” to follow, we must be grateful that the challenge was made and accepted—setting a standard for political argumentation, access, spontaneity, and stamina sorely lacking today.

Could you ever envision Lincoln-Douglas-style debates in 21st-century politics—that is, sustained argumentation of 60, 30, and 90 minutes with no restraint on audiences?

FJW: Our attention spans no longer allow for sustained listening. In addition, today’s televised candidate debates restrict time and presentations. Thus, the Lincoln-Douglas legacy has been lost.

EGM: Few politicians today would be able to keep audiences engaged for as long as Lincoln and Douglas did. One has only to recall the criticism presidents sustain when their speeches exceed one hour. In the era of the sound bite, we have become accustomed to our politicians delivering their message succinctly and, unfortunately, with a minimum of context. As for presenting such debates before an unrestrained audience, perhaps a 19th-century style of debating would not be so foreign to 21st-century voters. For all of the seriousness of the discussions, the 1858 debates were rife with instances of heckling, booing, fighting and other inappropriate responses from the audience. And both candidates seized upon the opportunity to ascribe motives and actions to his opponent that were sometimes inaccurate or downright untruthful. We sometimes think of political incivility as a phenomenon unique to our time. In truth, we are simply experiencing its latest iteration.

DLW: The differences between political debating in the 1850s and its counterpart in the 21st Century are perhaps only reflections of the differences in the prevailing cultures. For example, Douglas didn’t want to debate Lincoln and tried to avoid it when directly challenged. But at least two things contributed to his change of mind. One was that he resented Lincoln’s following closely in his wake and not only taking advantage of the crowds Douglas drew, but getting a chance to reply to Douglas’ speeches without Douglas being able to offer an immediate rejoinder. Another consideration making it hard to turn down Lincoln’s challenge was not only the risk of appearing afraid of his opponent, but of giving Lincoln the opportunity to point out in every subsequent speech that Douglas would not meet him face to face because he was unable to answer his criticisms and questions. These are all circumstances that take very different forms in contemporary campaigning, if they figure at all, mainly for two reasons: rapid transportation and the powerful new medium of television. In fact, where big names and consequential elections are in play, the “media” have a lot to say about how campaigns are managed, for they mediate not only breaking news on a 24-hour cycle, but the massive flow of targeted and sophisticated advertising. There was nothing remotely like this in the era of the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

HH: I learned a valuable lesson when I appeared on C-SPAN’s Booknotes 25 years ago to talk about my own, just-published Lincoln Douglas Debates. Host Brian Lamb asked me if I could imagine such lengthy encounters drawing crowds “today”— meaning 1994. No, I lamented, sound bites had replaced sustained discussion in politics. What a faux-pas! C-SPAN is entirely predicated on sustaining viewers’ sustained attention! Once the cameras were off, Lamb turned to me and whispered, “I think you’re wrong and I’ll prove it!” He went on to encourage and broadcast 21 hours of debates re-created on the sites where they had been staged in 1858. Thousands of spectators turned up to watch re-enactors debate afresh. The spectacles were broadcast live on his network and attracted tons of attention. That they did not spur modern politicians to aspire to such intense and protracted discussions saddens me. But that they reminded us of the energy and talent that animated these two giants in 1858 should please us enormously.

Harold Holzer is a Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. His next book is Monument Man, a biography of Lincoln Memorial Sculptor Daniel Chester French.