“One War at a Time”: Abraham Lincoln and the Monroe Doctrine in Latin America

Jason H. Silverman

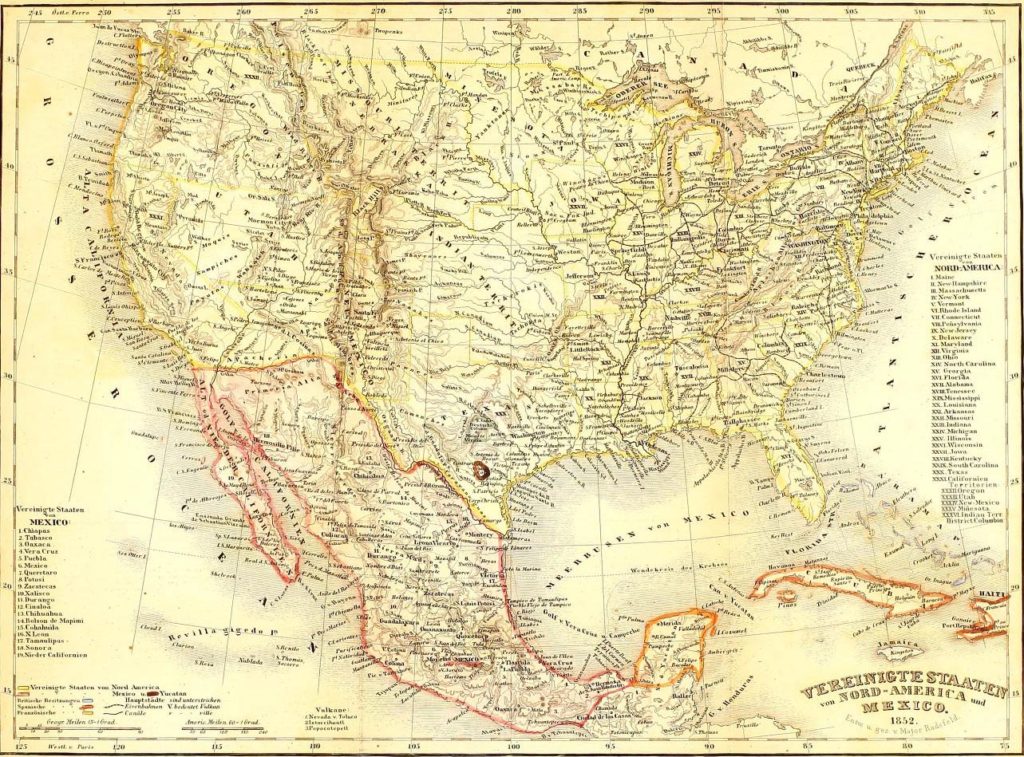

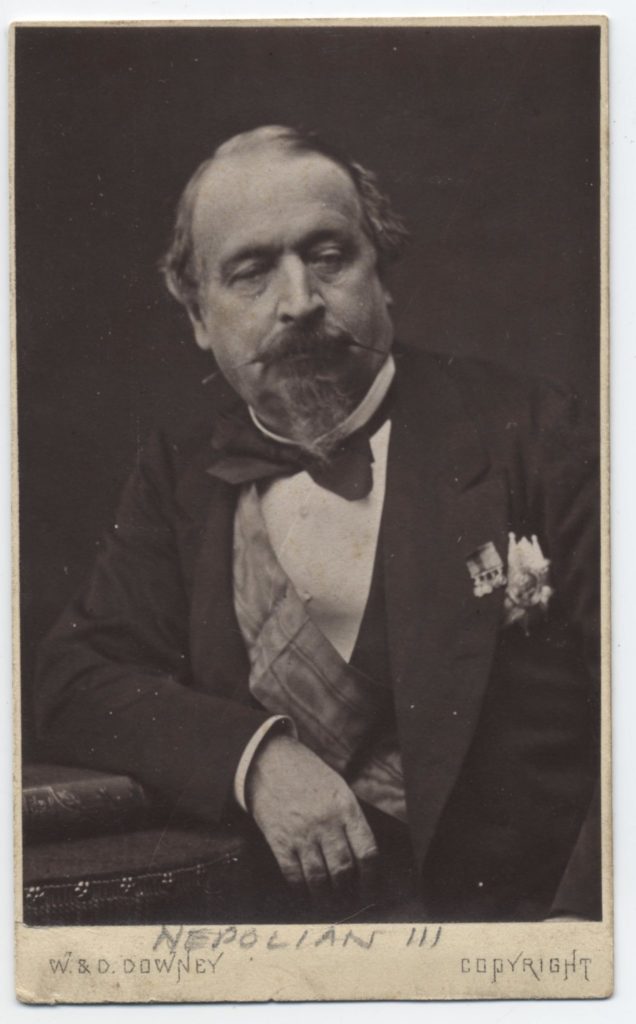

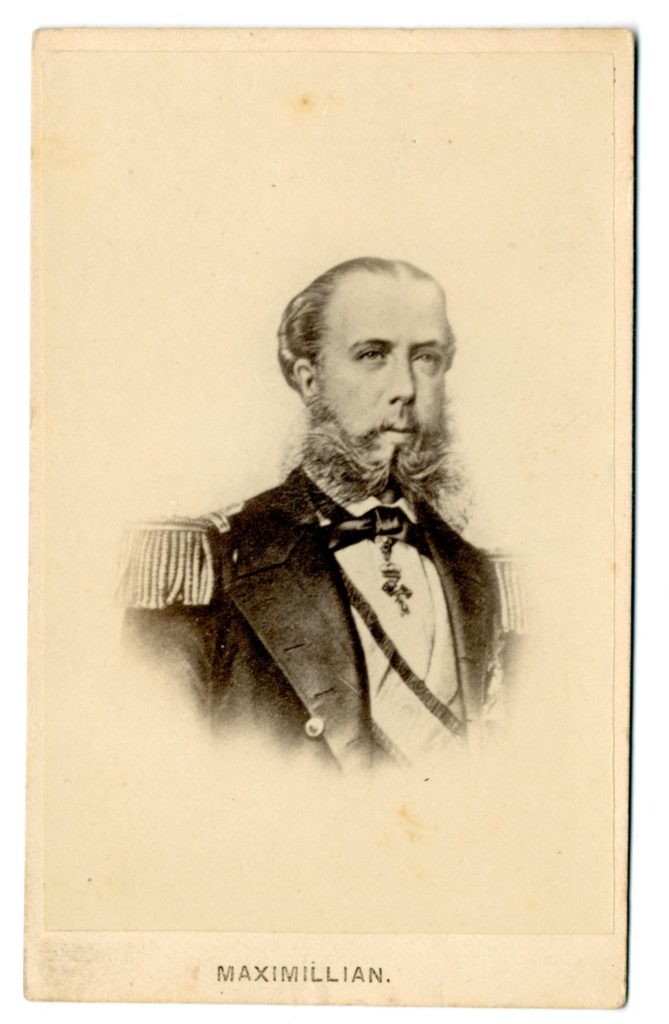

The darkening clouds of Civil War were not all the portentous developments that newly elected Abraham Lincoln faced when he arrived in Washington, DC. With the United States seemingly weakened by deep internal divisions, the European empires made one last attempt to regain their hold over North America and to reintroduce the “monarchic principle” into that “dangerous hotbed of republicanism.” Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria had an additional personal interest in the outcome of the American Civil War. On it hinged the existence of a new Hapsburg reign and the very life of his younger brother Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. But, Maximilian would never have ascended to the Mexican throne had it not been for yet another emperor, Napoleon III of France. Ever since Napoleon’s famous uncle sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803, France had no major stake in the Western hemisphere. With the advent of America’s Civil War, the French monarch sensed an opportunity to change that, with Maximilian as his puppet. Standing in the way of their plans was President Abraham Lincoln; while their natural allies became the newly created Confederate States of America.

Napoleon, Franz Joseph, and Maximilian, like most other crowned heads of their time, saw Lincoln as the personification of the republican ideas that had stoked the anti-monarchist revolutions in Europe. They naturally feared and hated Lincoln and hoped that the Civil War would provide them with an opportunity to exploit the American schism and re-establish monarchical regimes in America’s backyard.

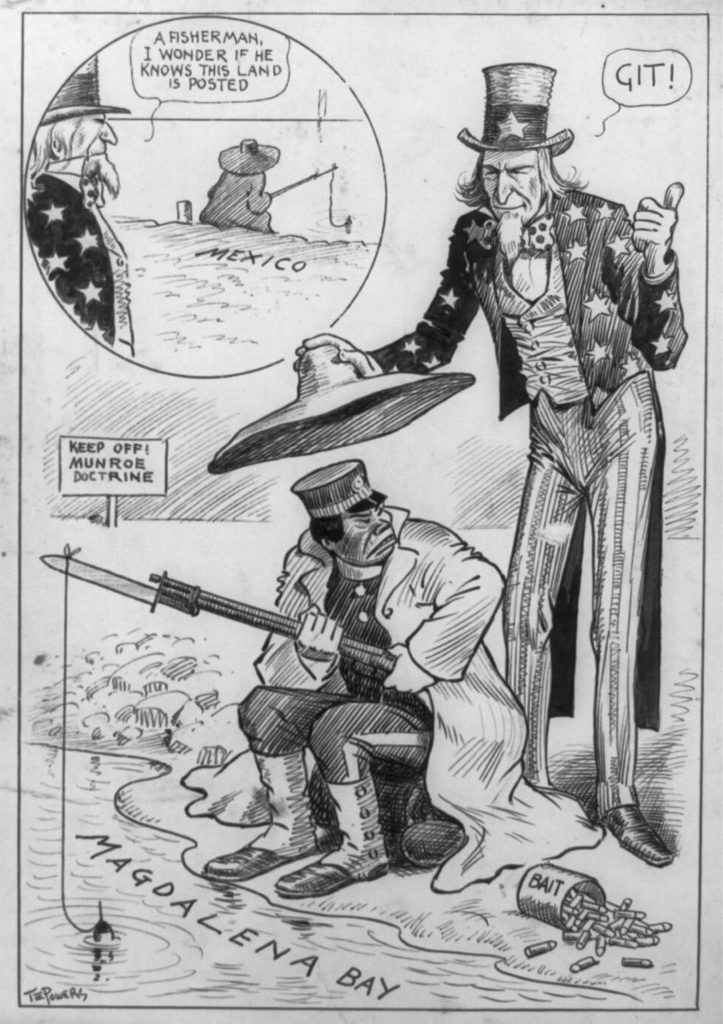

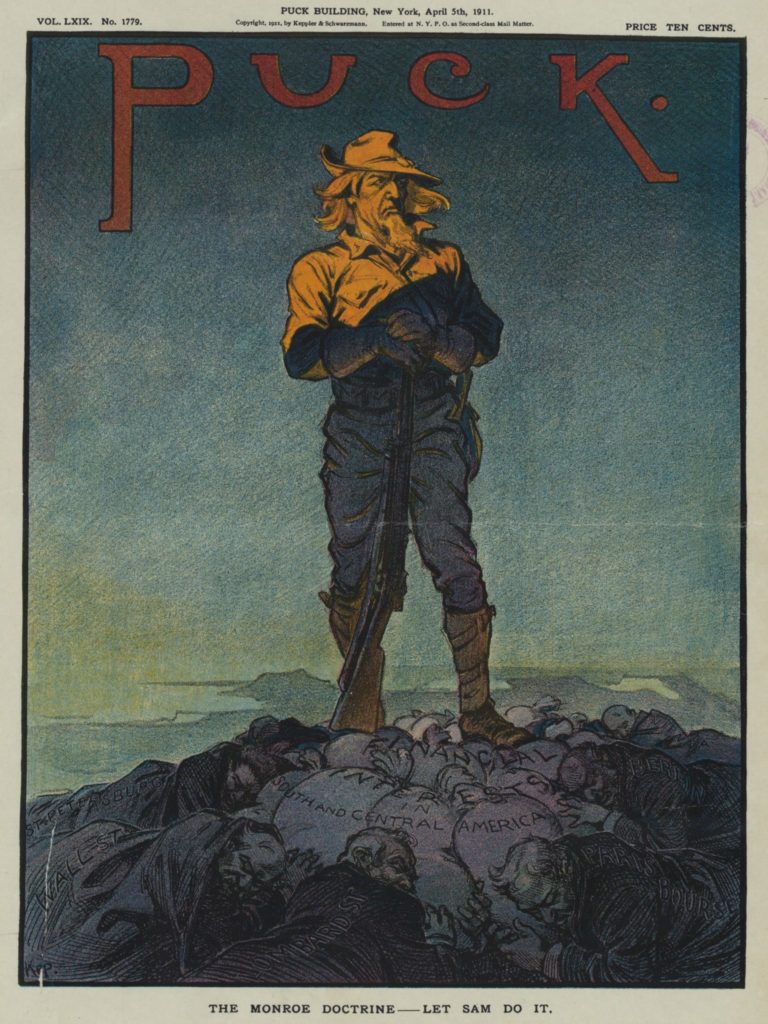

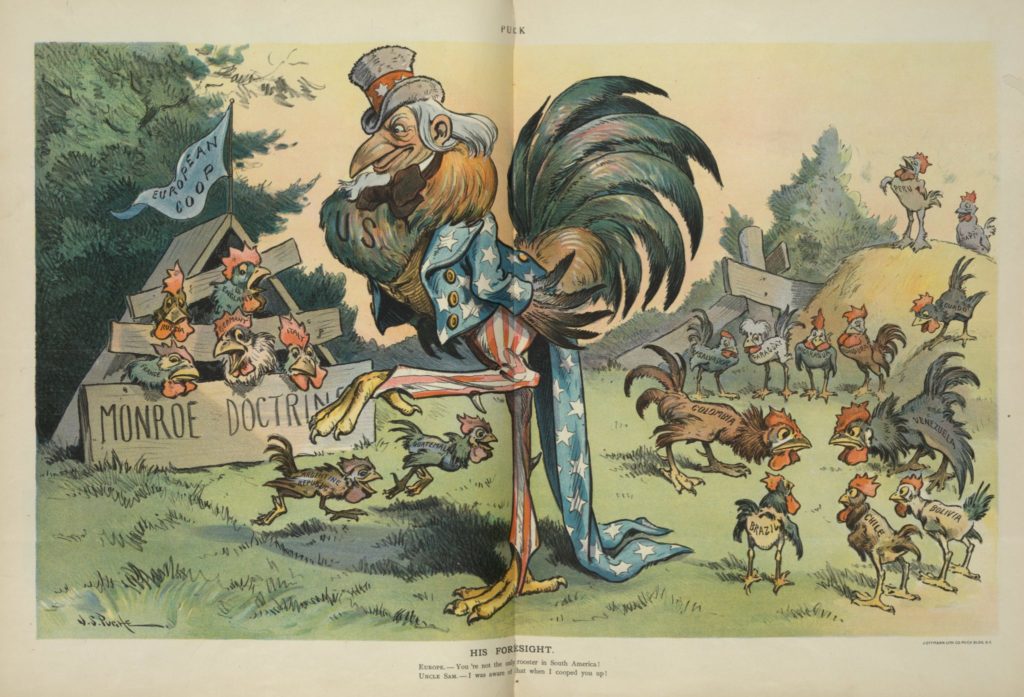

The struggle in its international aspects was reminiscent of the great struggle between revolutionary France and the ancien régime of Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. The American Civil War as well as the French Revolution precipitated an international coalition which lined up its forces against emerging Republics. In the case of the United States, the Republic was now split in two, and wisdom dictated a policy of intelligently and cautiously enforcing the Monroe Doctrine, first articulated in President Monroe’s Message to Congress on December 2, 1823, to protect hemispheric security from European encroachment, in the face of this new European challenge. This policy found its personification in Abraham Lincoln.

A slow but profound thinker, one who deliberated each and every action, a champion of tolerance who had immense respect for human life, Lincoln was anything but a born leader of armies. If not a pacifist at heart, Lincoln may aptly be described as “an unmalicious warrior,” as one biographer described him.

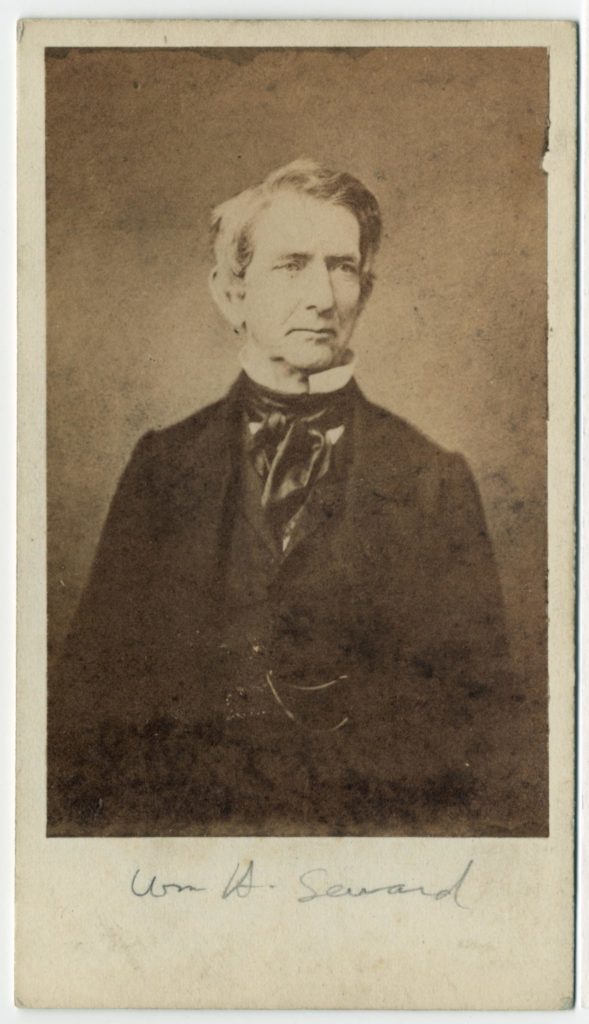

Those around him, however, were not as cautious as the President. Although an intelligent and shrewd politician, William Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, advocated an aggressive approach toward the European nations to stave off any thoughts they might have about violating the Monroe Doctrine. “I would demand explanations from Great Britain and Russia,” he told Lincoln, “and send agents into Canada, Mexico, and Central America, to raise a vigorous spirit of independence on this continent against European intervention, and, if satisfactory explanations are not received from France and Spain, would convene Congress and declare war against them.”

Lincoln’s view of the international situation, though, was uninfluenced by war psychosis or wishful thinking. He quietly shelved Seward’s foreign policy and substituted his own based on the simple and prudent maxim of “one war at a time.” While Lincoln stood firm in his defense of the Monroe Doctrine, he preferred a policy of common sense and reason to that of challenge and aggression.

Lincoln’s Latin American crisis, like his domestic one, grew out of sharp ideological differences. Lincoln’s commitment to the Monroe Doctrine precluded Napoleon’s attempt to establish on the southern frontier of the United States a strong monarchy as a barrier to further American expansion. It was Napoleon’s plan as well to convert the other Spanish American republics into monarchies similar to the Second Empire of France. The violation of both the Monroe Doctrine and the sovereignty of the Republic of Mexico initiated his “Grand Design for the Americas.” Consumed with his own war at home, Lincoln would have none of it. Creating a new Latin American policy, Lincoln and other New World statesmen attempted to unify the Americas against European monarchs and to a considerable degree succeeded.

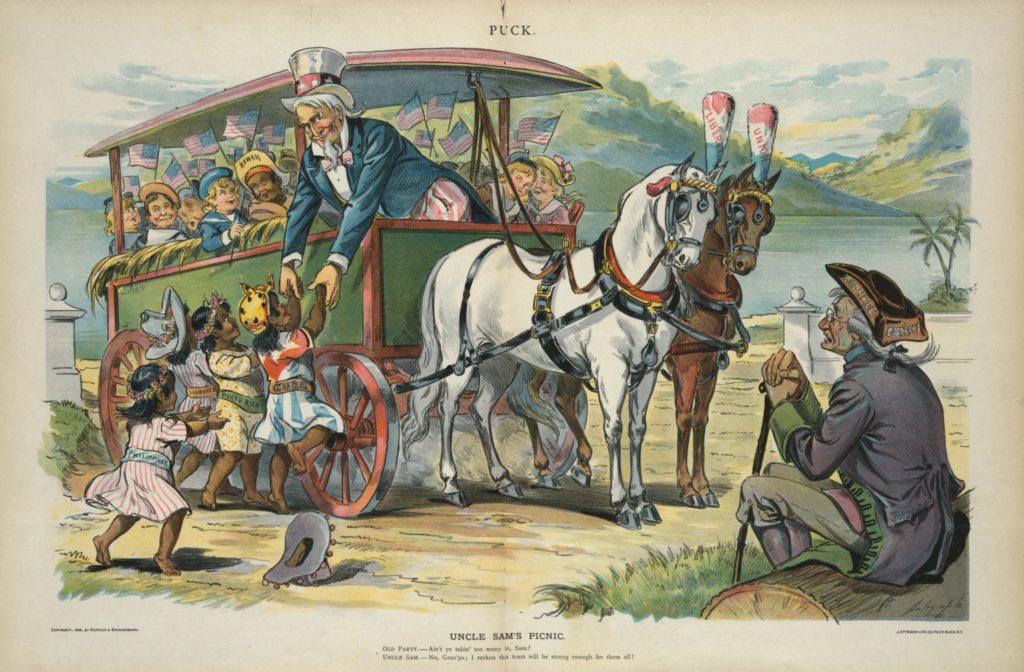

Lincoln drastically changed the U.S. policy toward Latin America by exercising rigid discrimination in sending there as ministers and other diplomats only those who could convince the Latin Americans that the United States no longer condoned slavery; had abandoned the ambition to expand its territory; and henceforth would extend the utmost respect and courtesies to the Latin Americans, especially in the settlement of claims. In Guatemala, adjoining Mexico on the South, Lincoln appointed Elisha O. Crosby of California who undertook to solve the problems created by Napoleon’s puppet Maximilian. In the extremely difficult post of minister to reactionary and pro-monarchical Ecuador was Austrian-born Friedrich Hassaurek who possessed such a crusading spirit for the expansion of human freedom that in his earlier career in Ohio he had become known as “the beer hall Demosthenes.” But Lincoln’s most immediate problem upon assuming office was Mexico and for that post he needed someone near perfect.

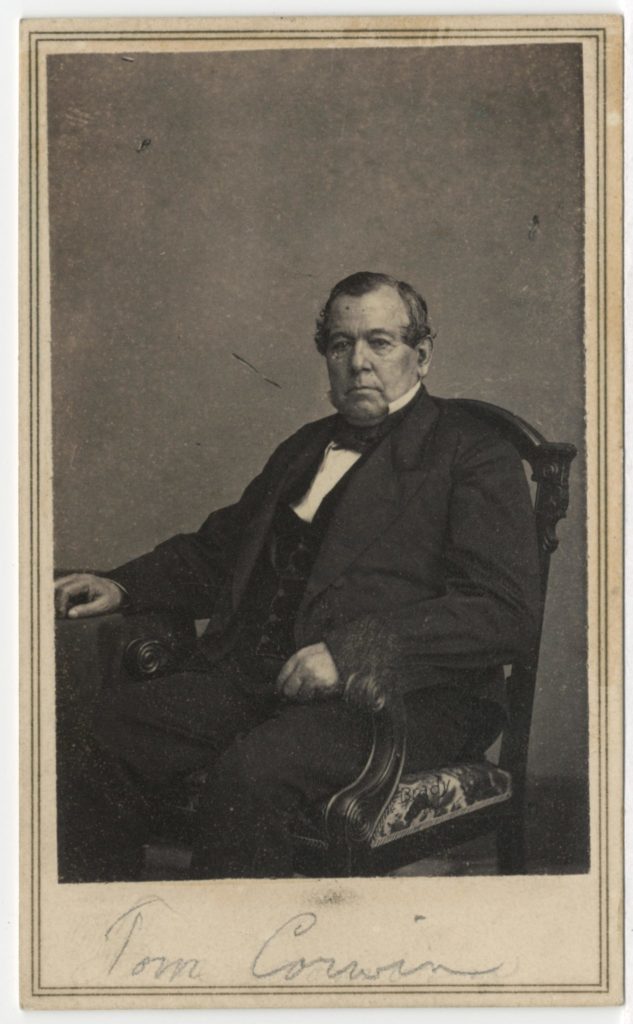

“Mexican affairs have suddenly come to be very interesting to the Black [Lincoln’s] Administration,” the confidential dispatch John Forsyth, former U.S. minister to Mexico, expressed to his Confederate colleagues from the Washington Peace Conference in late March of 1861. Earlier that month President Lincoln, while considering diplomatic appointments for England, France, Mexico, and Spain, had written, “We need to have these points guarded as strongly and quickly as possible.” Indeed, Mexico might become the most important foreign post, editorialized the New York Tribune, since it would counteract “the filibustering projects of the Southern Confederacy.” For the significant Mexican appointment Lincoln chose brilliant lawyer and noted orator, Thomas Corwin, a radical anti-expansionist. Lincoln’s choice was made after Secretary of State William Seward asserted that the post was “perhaps the most interesting and important one within the whole circle of our international relations.” With that appointment, the new president launched his foreign policy toward Latin America.

The Mexican diplomatic assignment was the crowning achievement to Corwin’s long, distinguished career. Formerly a member of Congress, governor of Ohio, United States senator and, secretary of the treasury in Millard Fillmore’s cabinet, Corwin’s oratory was so influential that it often shaped public opinion. So powerful was his opposition to the United States war against Mexico that he declared on the floor of the U.S. Senate his hope that the Mexicans would receive the invading armies “with bloody hands and hospitable graves.” For this statement he was widely hanged in effigy, even by members of his own party.

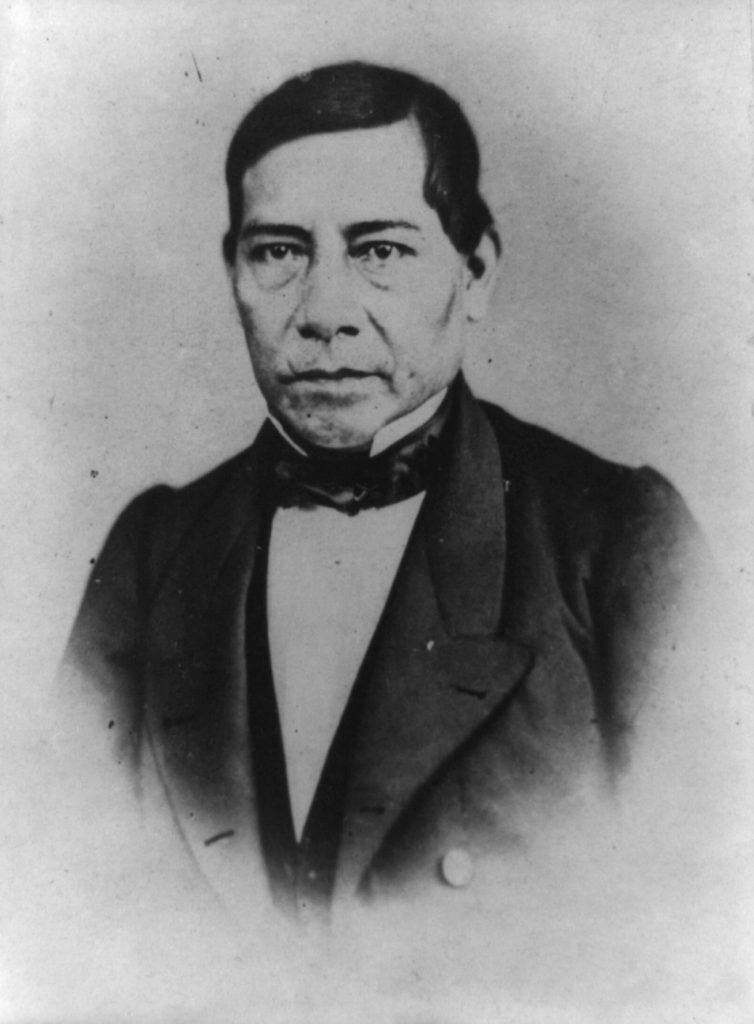

Lincoln instructed Corwin to do all that he could to combat both the Confederate and French influence in Mexico. He was to assure Mexico’s duly elected president and Maximilian’s adversary, Benito Juárez, that the American Civil War was inimical to the welfare of all republican governments in the Western hemisphere. Corwin was to oppose at all costs Confederate attempts to seek diplomatic recognition from Mexico, warning against any aggressive plans of the Confederacy, especially attacks from California and Texas. This he accomplished within a few months and with little difficulty.

Corwin’s second assignment was to initiate Lincoln’s new Latin American policy which was intended primarily to mitigate the previous administrations’ overzealous demands in regard to the American acquisition of Mexican land and the claims of loss of lives and property of United States citizens. In view of the threatened intervention of European monarchies, Corwin was to assure President Juárez that the United States desired Mexico to “retain its complete integrity and independence,” and wished it reinstate its form of republican government seemingly in exile. In the Mexican capital Corwin readily made friends with Mexican officials for whose problems he had both empathy and sympathy. “In the last forty years Mexico has passed through thirty-six different forms of government, has had . . . seventy-three Presidents.” Corwin wrote Seward. “Still I do not despair of the final triumph of free government. . . . The signs of regeneration, though few, are still visible. Had the present liberal party enough money at its command to pay an army of 10,000 men, I am satisfied it could suppress the present opposition, restore order and preserve internal peace…I am persuaded the pecuniary resources to effect these objects at this time must come from abroad. This country is exhausted…by forty years of almost uninterrupted civil war.”

By July 1861, Corwin received “positive assurance…that…the [Juarez government] will not entertain any proposition” leading to recognition of the Confederacy. Furthermore, Corwin wrote back to Seward that “well-informed Mexicans in and out of the Government seem to be well aware that the independence of a Southern Confederacy would be a signal for a war of conquest with a view to establishing slavery in each of the twenty-two states of the Republic [of Mexico].” Rumors rapidly spread that the Confederates were already referring to the Gulf of Mexico as “Confederate Lake.” Corwin had been at his post for little more than a month when John T. Pickett, the Confederacy’s diplomatic agent, landed at Veracruz with the assignment of neutralizing Corwin’s diplomatic headway.

Pickett’s mission had originated in March of 1861 while he was serving as secretary to the Confederate Peace Commissioners at the last ditch Washington Peace Conference. One of the commissioners, John Forsyth, recommended Pickett as one possessing a “thorough knowledge of Mexican character,” who knew the leaders and was “eminently suitable for a position so delicate and important.” This endorsement, however, was premature and misplaced. Indeed, Pickett was tactless and far from exemplary in his conduct, alternating between threatening language and unauthorized hints of bestowing patronage.

Pickett soon reported to the Confederate government that, in his opinion, there would be no stability in the Mexican government as long as the country was governed by Mexicans; only foreign intervention would bring about peace. The Confederacy demanded that Mexico observe the strictest neutrality in the American Civil War, and Pickett was instructed to use all means at his disposal “to match the proceedings of…and to counteract” the Lincoln administration.

Pickett informed his superiors that Mexico supported the Confederacy because slavery was similar to Mexican peonage, and the South was sincere in comparison with Northern hypocrisy. Such was the sympathy between Southerners and Mexicans that, if secession did not result in the independence of the South, “hundreds of thousands” of her sons would emigrate “with their goods and chattels (as did the children of Israel) to some convenient and attractive [Mexican] Promised Land.”

With Lincoln’s blessing, Corwin took a wait and see approach to the aggressive Pickett. But the situation changed dramatically when Pickett learned that the Juárez government had given the Union permission to march troops from Guaymas, on the Gulf of California, to Arizona, in order to protect Arizona from a suspected Confederate advance. In a bold move to undercut the Lincoln administration, Pickett promised the Mexican government “proposals for the retrocession to Mexico of a large portion of the territory hitherto acquired from her by the United States” (i.e. Texas, California, New Mexico territory, Arizona territory, and all other land obtained in the Mexican American War).

Nevertheless, by the early Fall of 1861, Mexico regarded the Confederacy with unmitigated suspicion. Pickett blamed Corwin and the Lincoln administration for creating this distrust. President Lincoln knew that Mexico’s immediate dangers were not necessarily from the Confederacy; rather, it was Mexico’s empty treasury, its continued internal unrest thanks to Napoleon and Maximilian, and the demands made by the European powers. Money was the lifeline of the Juárez government, and Lincoln was Mexico’s only prospect of getting it. As a Confederate emissary in Mexico wrote to the government in Richmond, the Mexicans believed that men, money, and arms would be “lavishly supplied” by the United States in support of the national integrity of Mexico and of the Monroe Doctrine.

It was not long before Pickett reluctantly conceded that, unlike the Lincoln administration, the Confederacy had “few or no friends” in Mexico. Pickett had been arrested for disorderly conduct in a bar and his “confidential” reports to Richmond with many unflattering remarks about Mexico had been intercepted in New Orleans and shared with the Juárez government. His mission to Mexico was relegated to utter failure.

When the Juárez government rejected the Confederacy’s overtures, it became expendable to the government in Richmond. The Confederacy, in an effort to win diplomatic recognition in Mexico from France, accepted Maximilian and hoped for an alliance with his government. Indeed, Confederate agents argued in Paris that success of the French Mexican government depended upon a Confederate victory in the United States. When Pickett left Mexico in December 1861, he was absolutely convinced that French intervention on behalf of the Confederate States was a certainty.

As danger from the Confederacy subsided, the Lincoln administration turned its attention to the larger problem of European intervention in Mexico. Lincoln could not spare any military assistance to Mexico as his own war clouds were getting darker and more ominous. Thus the only recourse for Lincoln to assist Mexico was money from loans, which would be effective only if England, France, and Spain agreed to settle peacefully their claims on Mexico.

With this in mind Corwin recommended to Lincoln that the United States loan Mexico an amount not exceeding $10,000,000 to $12,000,000, payable in installments. In return the United States might receive Baja California, thought to be in danger of seizure by the Confederates, or, alternatively, a tariff reduction on imports. Such an arrangement would doubtless be unpopular in both countries, Lincoln realized, remembering vividly his own opposition to the acquisition of Mexican territory during his one term in Congress.

Corwin then made a second suggestion to Lincoln. Corwin anticipated that England and France intended to intimidate Mexico or, worse yet, intervene militarily. “Europe is quite willing to see us humbled,” Corwin wrote, “and will not fail to take advantage of our embarrassment to execute purposes of which she would not have dreamed had we remained at peace.” Corwin concluded that President Juárez and his republican government, if given financial aid, could withstand any foreign intervention in their country. Only from the United States could such aid come. At the same time that Lincoln was seeking to assist Mexico, the Mexican Congress inopportunely suspended interest payments on debts and claims owed England, France, and Spain. Corwin quickly proposed that the United States pay Mexico’s suspended interest obligations, taking as security the mining rights of the northern states of Mexico. The American loan, then, would be specifically designed to assist the Mexican debt settlement. For the United States to pay debts other than its own was an unprecedented move and it was highly unlikely that England and France would permit the Unites States to pay Mexican debts and thereby gain further influence in that country.

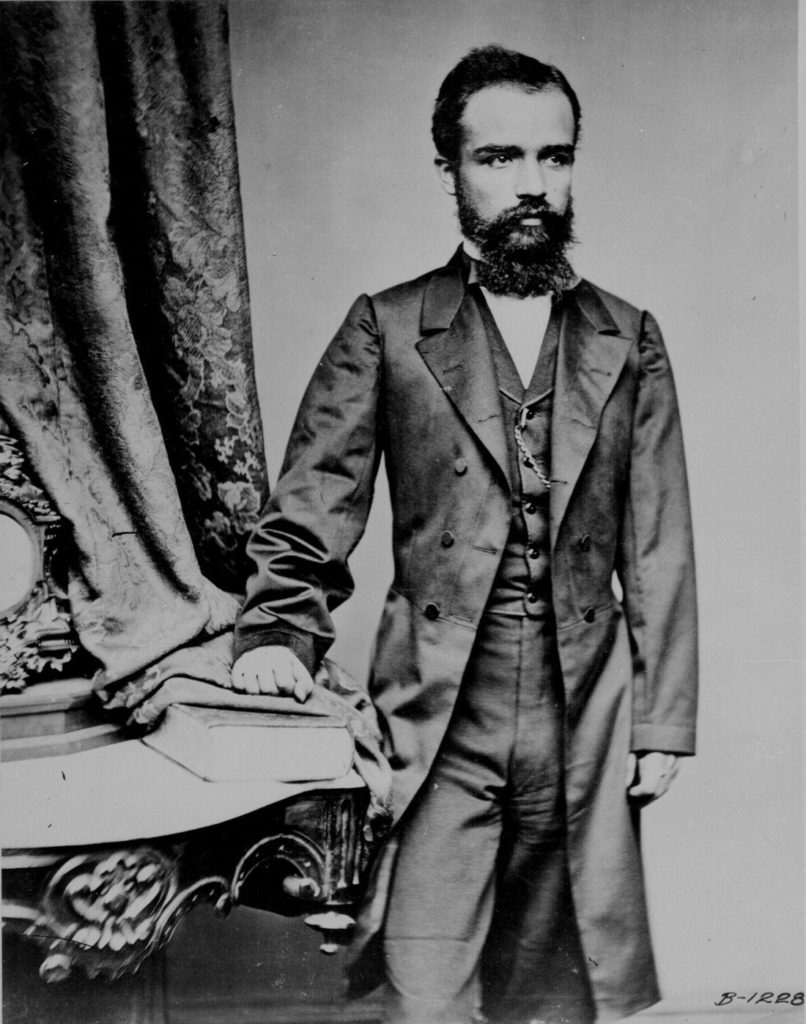

To Lincoln, and to his own Mexican countrymen, the youthful Mexican diplomat, Matías Romero argued futilely in behalf of a general loan to his country. But Mexican Foreign Minister, Manuel María Eutimio de Zamacona refused to consider the price: “It is inconceivable,” he declared, “that this government would make agreement about the sale of territory . . . or mortgage the wealth of undeveloped lands . . . which would foreshadow any danger to our nationality.” Both Lincoln and Seward convinced Romero that, the Monroe Doctrine notwithstanding, a loan to Mexico would never be approved by either the Department of State or the Senate if the money was used to make war on other powers, especially in the midst of an American Civil War. This would risk an international crisis and Lincoln resorted once again to his “one war at a time” philosophy.

If a general loan to Mexico was not feasible, then perhaps one earmarked to meet the interest payments on the Mexican debts might work, Lincoln was advised by Seward. Thus on August 24, 1861, Lincoln and Seward gave Corwin permission to pursue such negotiations. Corwin was authorized to frame a treaty by which the United States would pay, “over a period of five years, the interest of 3 percent on Mexico’s funded foreign debt. Repayment would bear 6 percent interest and the loan would be secured by public lands and mineral rights in the northern states of Mexico.” The treaty was not to be signed until and unless Britain, France, and Spain agreed not to make reprisals. By the following month, the proposed American treaty with Mexico became well known in London and Paris. Charles Francis Adams, U.S. minister to London brought the question to the attention of British Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell and informed Russell that the United States was disturbed by rumors of interference in Mexico and the possibility of the creation of a new Mexican government by foreign intervention. Adams insisted that it would be much better if the threatened use of force by the European powers were prevented by an agreement whereby the United States guaranteed, for a specified period, interest payments on Mexican debts.

Despite their initial reluctance, Lincoln and Seward recognized the validity in the proposal to pay Mexico’s interest payments. It was a calculated risk to be sure, Lincoln thought. But, much to Lincoln’s chagrin, when the resolution endorsing the project of a loan was brought to the floor of the U.S. Senate, it was decisively rejected, and instead an opposing resolution was adopted declaring that it was not advisable to negotiate a treaty that would require the United States to assume any portion of the principal or interest of the debt of Mexico, or that would require the concurrence of foreign powers. Despite Lincoln’s lobbying, the Senate would not approve any loan that would drain money from Civil War expenditures.

Lincoln regarded European intervention in Mexico as only slightly less threatening than the rebellion at home. An aggressive Britain, France, and Spain might start a war which could result in the complete subjugation of Mexico. If that took place and the Confederacy prevailed, the outcome could once again be a return “of the American continent under European domination.” As 1861 faded, Abraham Lincoln watched with grim uncertainty the unfolding situation in Mexico.

Mexico was rapidly becoming one of the most compelling elements of the Lincoln Latin American foreign policy. The foreign policy toward Latin American established in Mexico by Lincoln, continued by his successor, President Andrew Johnson, and administered throughout both administrations by Secretary of State Seward, was gradually applied to the other Latin American republics.

As was the situation in Mexico, advocates of monarchy in most of the Latin American countries were from conservative and clerical groups. These groups came from deeply rooted positions of power and wealth which had “suffered disastrously . . . under the republican form of government.” In dire terms, Friedrich Hassaurek, American minister to Ecuador, reported such to President Lincoln. “We must either…be swallowed up in the end by the Anglo-Saxon race or follow the example of the French in Mexico…Bad…as foreign intervention may be, it is our last and our only hope.” Prior to the Lincoln administration, the American State Department had so relentlessly persisted in pro-annexationist claims as to alienate and anger the Latin American nations. As Manifest Destiny spawned aggressive expansionists who professed that Anglo-American dominance was a heaven-sent process ordained by God, Latin American resentment, fear, and hatred were intensified.

Despite being consumed by his own war, Lincoln realized that the American relationship with Latin America must be repaired and improved. That attitude was shared by the Mexican diplomat Matías Romero. “Before the [U.S.] Civil War commenced,” Romero wrote, “it appeared that…[the United States] was the only enemy …because [its] usurping policy had deprived us of half our territory and [was] a constant menace…Nothing, therefore, was more natural than to see with pleasure…a division which…would render [America] almost impotent against us . . . [However] We [now] find ourselves [facing] the hard alternative of sacrificing our territory and our nationality at the hands of…[the United States] or our liberty and our independence before the despotic thrones of Europe. The second danger is immediate and more imminent…”

Lincoln’s plans were intended to rectify the mistakes of the past and to eschew the traditional American expansionist pressure on Latin America and create a new foundation of mutual understanding and self-respect. Toward that end, Lincoln’s instructions to American diplomats in Spanish America constituted “an emotionally earnest crusade for the survival of free institutions.” This included the condemnation of slavery, long abolished in free Spanish America, and the vigorous defense of human and natural rights. The antithesis of this Lincoln believed was the Confederacy which he described as composed of filibusterers and expansionists, intent on the spread of slavery into Latin America with its ultimate intention of overthrowing legally constituted governments. Ever the successful and compelling trial lawyer, Lincoln also indicted Confederate policies by linking them closely with the aggressive foreign policies of French and Spanish imperialism directed toward the Latin American nations. This vastly departed from Lincoln’s predecessors, and, along with Secretary of State Seward, he assured the Spanish American republics that the “United States was the one powerful defender of republicanism against monarchy and Old World interference and, therefore, the protector of all sovereignty in the Western Hemisphere.”

Although overshadowed by the myriad of his domestic woes and his concerns that European nations would interfere in the American Civil War, Lincoln was a quiet, yet staunch, defender of the Monroe Doctrine. And, while his foreign policy initiatives were obviously designed to preserve the Union, Lincoln never took his eye off European encroachment elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere and sought to stop it wherever it existed.

Two years after Lincoln’s assassination, Napoleon’s Grand Design failed of its own weakness. Although Lincoln’s attempt to loan Mexico funds was thwarted on the floor of the Senate he had, during his administration, quietly ignored the unofficial assistance that the United States Army occasionally provided Mexico in the form of war materiel. “We have obtained our victory,” an exuberant, if not slightly mistaken, Romero wrote, “by our own efforts without the aid of any foreign nation—in spite of the moral influences of all Europe and the material force of France and the continental powers. We have opposed the gigantic combination with nothing more than the suffering and patriotism of our people and the firm sympathy of the United States.”

Not exactly. The quiet and wise upholding of the Monroe Doctrine by Abraham Lincoln provided more than sympathy. It provided invaluable diplomacy at a time when Lincoln’s thoughts were consumed by the carnage at home. At just the right time, Lincoln became, as one historian wrote many years ago, a perceptive, compassionate, and unpretentious “diplomat in carpet slippers.”

Jason Silverman is Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History Emeritus at Winthrop University.