Abraham Lincoln on Civil Liberties

By Hon. Frank J. Williams

Imagine, if you will, that the United States suffers an unexpected attack. The president deploys the armed forces and assumes extraordinary powers that go well beyond what the Constitution seems to allow. Thousands of persons suspected of aiding the enemy are arrested and held without charge, or tried before military tribunals. Talk abounds of deporting members of a particular ethnic group from the country. The president meets frequently with evangelical ministers, trying to assure their active support for his military conflict as an epic struggle between good and evil, inspired by the country’s divinely-appointed mission to spread freedom and democracy throughout the world.

This period is not the early twenty-first century. Instead, the period is the 1860s, the president, Abraham Lincoln, and the conflict the American Civil War. History never really repeats itself. But the uncanny resemblances between that era and events in the United States since September 11, 2001 have pushed to the forefront of historical discussion such questions as the status of individual rights in a national emergency and the permissible limits on the rule of law in wartime.

“Congressional leaders were outraged by the president’s decision to deny American citizens a most basic constitutional right.”

“Newspaper editors condemned the president. Lawyers, jurists, civic leaders, academicians, clergy, and others joined in the attack.”

“It was not believed that any law was violated,’ the president said in response to his many critics.”

Is this a news clipping from 2001 through 2007, during President George W. Bush’s decision to authorize wiretaps without court approval, to detain both U.S. & non U.S. citizens accused of terrorist acts without charging or trying them?

Though such a conclusion would be understandable, it, too, is wrong. Rather, the clipping describes the reaction to President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, detain U.S. citizens, and to try them before a military tribunal.

Lincoln has always provided a lens through which Americans examine themselves. Every generation reinvents Lincoln in its own image. He has been variously described as a consummate moralist and a shrewd political operator, a lifelong foe of slavery and an inveterate racist.

Today, people, governments, and businesses can communicate at the touch of a button. It’s hard to remember a day without the internet, but its introduction and assimilation into daily life was a mere twenty years ago. Despite our advances, our country has entered a time separate from, yet similar to, the time of President Lincoln’s administration.

Since 2001, our country has lived in a shadow cast by the September 11, 2001 attacks. The detention of enemy combatants and President Bush’s decision to allow military tribunals spawned much heated discussion world-wide and within our nation. President Barack Obama campaigned against military detentions and for closing Guantanamo Bay in his election 2008 election campaign. When he was elected, he temporarily stopped the use of military tribunals, but within months reinstituted their use. Throughout his administration, President Obama continued many of President Bush’s same policies. Today, President Donald Trump is intent to follow a similar path that both Presidents Obama and Bush traveled. In making this choice to utilize such tribunals, our commanders-in-chief walk a fine line between protecting the civil liberties all Americans hold so dear, and guarding the safety of each citizen.

Throughout our nation’s history, our leaders have been criticized for taking seemingly extra-constitutional measures. Upon closer examination of the situations facing Abraham Lincoln, many parallels can be drawn to the current atmosphere in this country. Today, years after the start of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, our country still lives in the shadow caused by the attacks on September 11, 2001. Today, not only does our nation have a continuing presence in both those nations, but is fighting a new threat: ISIS; along with Al Qaeda, and many other terrorist organizations. But to fight terrorist organizations, and not countries, required and still requires a different set of rules than the set we have used since the inception of our nation.

In facing emergencies during the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln found himself in many difficult political positions. In the words of historian James G. Randall: “No president has carried the power of presidential edict and executive order (independently of Congress) so far as he did . . . It would not be easy to state what Lincoln conceived to be the limit of his powers.”

It has been noted how, in the eighty days between the April 1861 call for troops at the beginning of what became the Civil War and the convening of Congress in special session on July 4, 1861, Lincoln performed a whole series of important acts by sheer assumption of presidential power:

- increased the size of the army and navy;

- appropriated money for the purchase of arms and ammunition without congressional authorization;

- declared a blockade of the southern coast which is an act of war, which, arguably, recognizes a belligerent nation

- and, of course, suspended the precious privilege of the writ of habeas corpus.

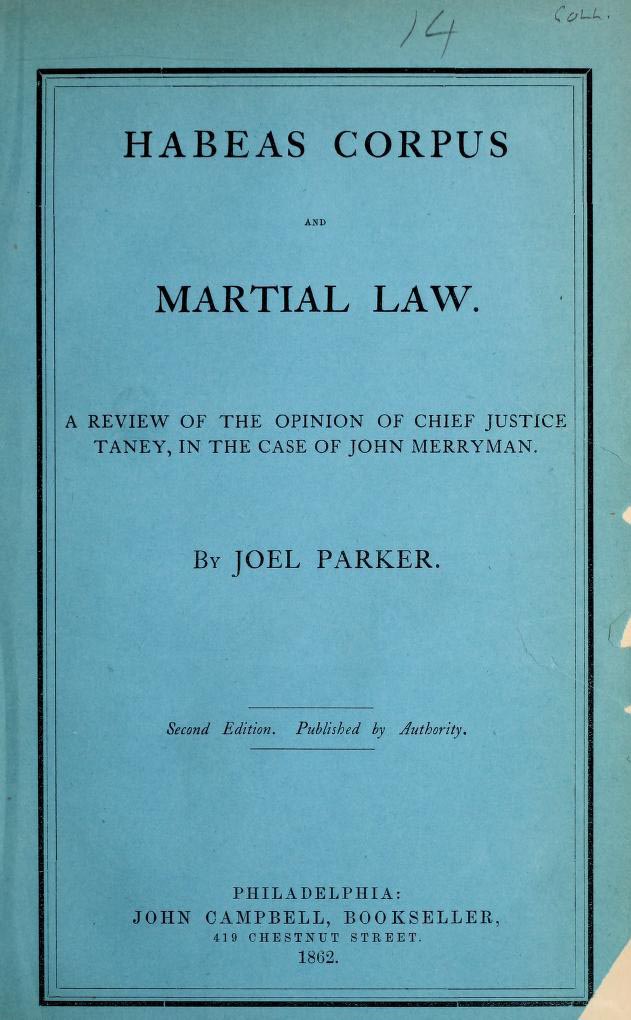

The writ of habeas corpus is a procedural method by which one who is imprisoned can petition the court to have his or her imprisonment reviewed. If court finds the imprisonment does not conform with the law, the individual is entitled to immediate release. With suspension of the writ, this immediate judicial review of the imprisonment becomes unavailable. This suspension triggered the most heated and serious constitutional disputes of the Lincoln administration.

We all know that only Congress is constitutionally empowered to declare war, but suppression of rebellion has been recognized as an executive function, for which the prerogative of setting aside civil procedures has been placed in the President’s hands.

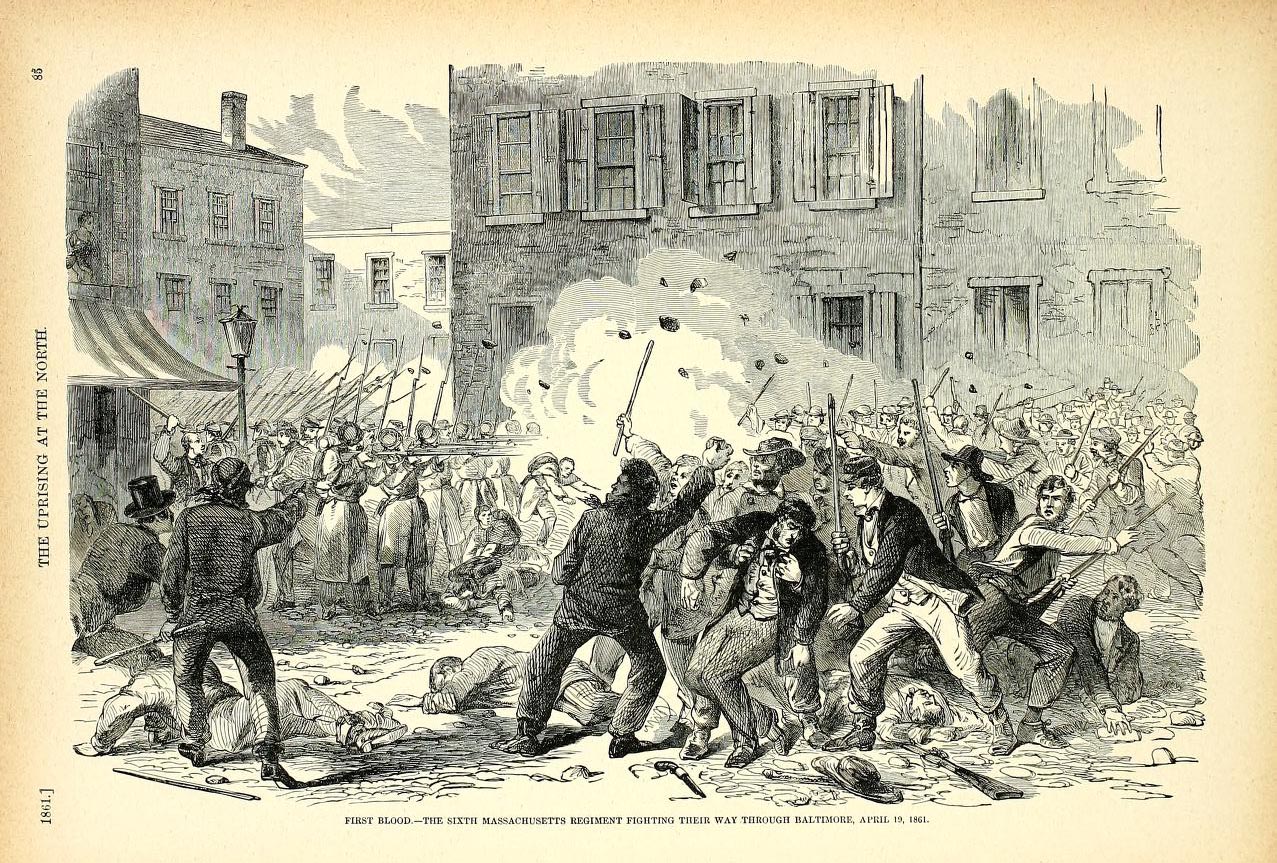

By 1861, events in Maryland ultimately provoked Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Lincoln’s defenders argued that “events” had forced his decision. Ft. Sumter was fired upon on April 12, 1861. On April 19, the Sixth Massachusetts militia arrived in Washington after having literally fought its way through hostile Baltimore. On April 20, Marylanders severed railroad communications with the North, almost isolating Washington D.C. from that part of the nation for which it remained the capital. Lincoln was apoplectic.

He had no information about the whereabouts of the other troops promised him by Northern governors, and Lincoln told Massachusetts volunteers on April 24, “I don’t believe there is any North. The Seventh Regiment is a myth. Rhode Island is not known in our geography any longer. You are the only Northern realities.”

On April 25, the Seventh New York militia finally reached Washington after struggling through Maryland. The right of habeas corpus was so important that the President actually considered the possible bombardment of Maryland cities as an alternative to suspension of the writ. Lincoln authorized General Winfield Scott, Commander of the Army, in case of “necessity,” to bombard the cities, but only “in the extremist necessity” was Scott to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.

In Maryland, there was at this time a dissatisfied American named John Merryman. Merryman’s dissent from the course being chartered by Lincoln was expressed in both word and deed. He spoke out vigorously against the Union and in favor of the South. He destroyed bridges and tore down telegraph lines isolating Washington, D.C. from the rest of the nation. Thus, he not only exercised his Constitutional right to disagree with what the government was doing, but engaged in attacks to destroy the government.

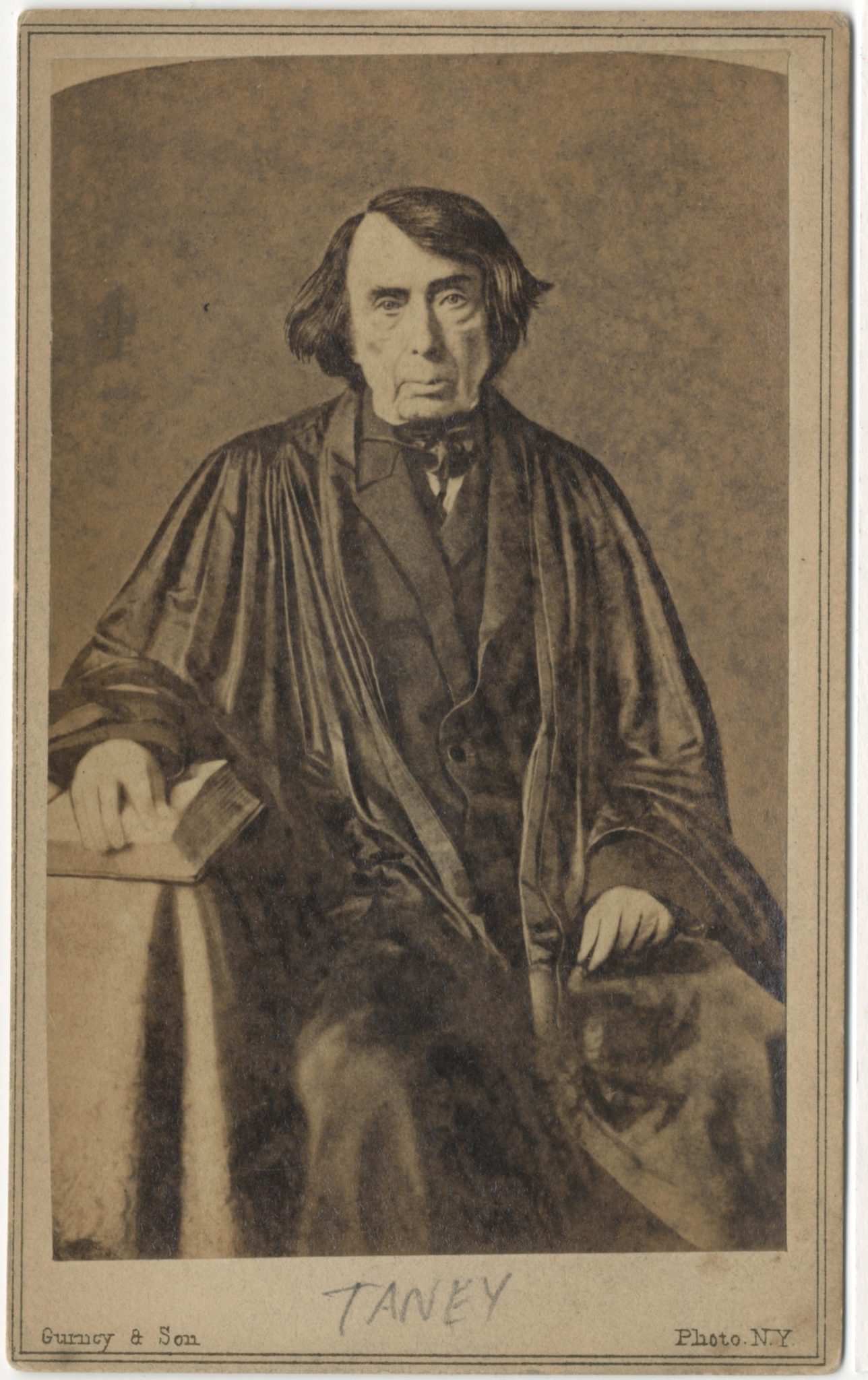

This young man’s actions precipitated legal conflict between the President and Chief Justice of the United States, Roger B. Taney.

On May 25, 1861, Merryman was arrested by the military and lodged in Fort McHenry, Baltimore, for various alleged acts of treason. Shortly after Merryman’s arrest, his counsel sought a writ of habeas corpus from Chief Justice Taney, alleging that Merryman was being illegally held at Fort McHenry.

Taney, already infamous for the Dred Scott decision, took jurisdiction as a Circuit Judge. On Sunday, May 26, 1861, Taney issued a writ to fort commander George Cadwalader, himself an attorney, directing him to produce Merryman before the Court the next day at 11:00 a.m. Cadwalader respectfully refused on the ground that President Lincoln had authorized the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

To Taney, Caldwalader’s actions were constitutional blasphemy. He immediately issued an attachment for Cadwalader for contempt. The marshal could not enter the Fort to serve the attachment, so the old justice, recognizing the impossibility of enforcing his order, settled back and produced the now famous opinion, Ex Parte Merryman.

Notwithstanding the fact that he was in his eighty-fifth year, the Chief Justice vigorously defended the power of Congress alone to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. The Chief took this position in part because permissible suspension was in Article I § 9 of the Constitution, the section describing Congressional duties. He ignored the fact that it was placed there by the Committee on Drafting at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 as a matter of form, not substance. Nowhere in his written decision did he acknowledge that a rebellion was in progress, and that the fate of the nation was, in fact, at stake. Taney missed the crucial point made in the draft of Lincoln’s report to Congress on July 4, 1861:

“The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed, were being resisted, and failing of execution, in nearly one-third of the States. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution? [A]re all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?”

By addressing Congress, Lincoln had ignored Taney. Nothing more was done about Merryman at the time. Merryman was subsequently released from custody and disappeared into oblivion. Two years later, Congress resolved the ambiguity in the Constitution and permitted the President the right to suspend the writ while the rebellion continued.

Five years later, after the war, the Supreme Court reached essentially the same conclusion as Taney in a case called Ex Parte Milligan. The Court in Milligan said that habeas corpus could be suspended, but only by Congress; and even then, the majority said civilians could not be held by the Army for trial before a military tribunal, not even if the charge was fomenting an armed uprising in a time of civil war where the civil courts were operating as they were in Indiana, unless Congress authorized such tribunals.

Lincoln never denied that he had stretched his Presidential power. “These measures,” he declared, “whether strictly legal or not, were ventured upon, under what appeared to be a popular demand, and a public necessity; trusting, then as now, that Congress would readily ratify them.” They did in summer 1861.

Lincoln thus confronted Congress with a fait accompli. It was a case of a President deliberately exercising legislative power, and then seeking congressional ratification after the event. There remained individuals who adamantly believed that in doing so he had exceeded his authority.

Ohioan Clement Laird Vallandigham, the best-known anti-war Copperhead of the Civil War, was perhaps President Lincoln’s sharpest critic. He charged Lincoln with the “wicked and hazardous experiment” of calling the people to arms without counsel and authority of Congress; with suspending the writ of habeas corpus; and with “cooly” coming before the Congress and pleading that he was only “preserving and protecting” the Constitution and demanding and expecting the thanks of Congress and the country for his “usurpations of power.”

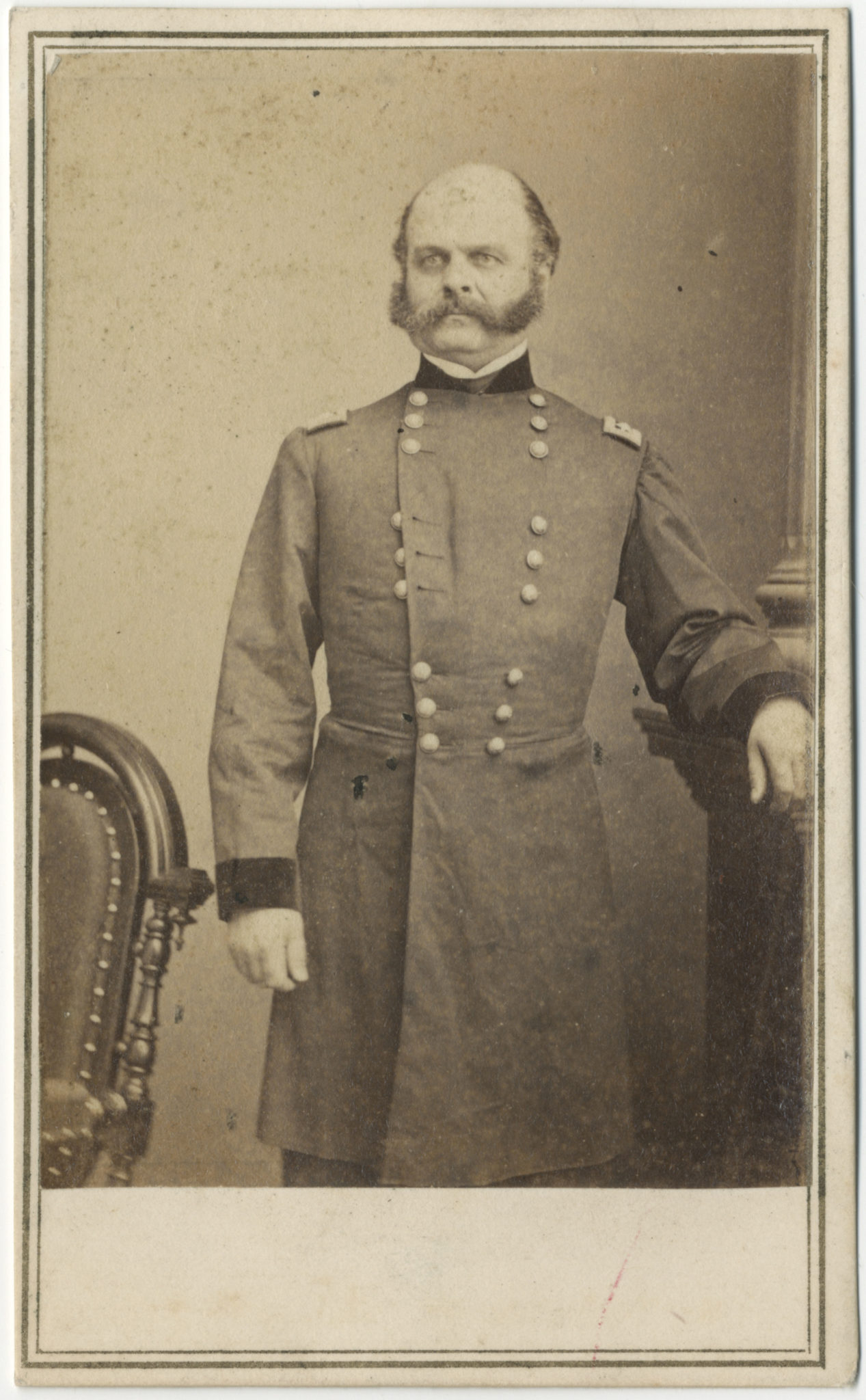

Vallandigham was speaking at a Democratic mass meeting at Mt. Vernon, Ohio, on May 1, 1863, when he was arrested by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside. He was escorted to Kemper Barracks, the military prison in Cincinnati and tried by a military commission. He was found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment for the duration of the war.

After being denied a writ of habeas corpus, he applied for a writ of certiorari to bring the proceedings of the military commission for review before the Supreme Court of the United States.

In the Supreme Court’s opinion, Ex Parte Vallandigham, his application was denied on the grounds that the Supreme Court had no jurisdiction over a military tribunal.

Of course, when the Court addressed the issue in Ex Parte Milligan, after the war was over, it held that the writ of habeas corpus could only be suspended by Congress. The Court stated that

“[t]his court has judicial knowledge that in Indiana the Federal authority was always unopposed, and its courts always open to hear criminal accusations and redress grievances; and no usage of war could sanction a military trial there for any offence whatever of a citizen in civil life, in nowise connected with the military service.” Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2, 121–22, 18 L. Ed. 281 (1866).

Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus was specifically ratified by Congress at the end of 1862 permitting suspension nationwide.

Many years later, in 1942, the United States Supreme Court decided Ex Parte Quirin, a case in which civil German saboteurs detained for trial by military commission appealed a denial of their motions for writ of habeas corpus. The Supreme Court, refusing to review the case, held that “military tribunals … are not courts in the sense of the Judiciary Article [of the Constitution].” Rather, they are the military’s administrative bodies to determine the guilt of declared enemies, and pass judgment.

Ex parte Quirin became the foundation of President Bush’s claim that the government has the right to hold “enemy combatants” – even Americans – indefinitely, without evidence, charge or trial. That legal basis is still used today, despite President Obama’s attempt to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay. President Trump has stated publicly that he not only intends to keep Guantanamo Bay in use as a military prison, but that he hoped to add other enemy combatants there.

Others used the military trials of the conspirators of John Wilkes Booth, who helped Booth assassinate President Lincoln. During that time, the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, wished to convict the conspirators in a military tribunal, while Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and former Attorney General Edward Bates both argued it was unconstitutional. President Andrew Johnson requested that the sitting Attorney General James Speed write an opinion on the legality of a military trial for the conspirators. Speed concluded his memorandum, stating:

“[I]f the persons who are charged with the assassination of the President committed the deed as public enemies, as I believe they did, and whether they did or not is a question to be decided by the tribunal before which they are tried, they not only can, but ought to be tried before a military tribunal.”

After Speed wrote the memorandum, President Johnson ordered the use of a military commission for trial, and after a seven week trial, all were convicted. Some were sentenced to be hanged, while others were sentenced with prison terms from life imprisonment to six years in prison.

I never thought, as a veteran, lawyer, and a judge, that I would be living through a situation where the issue of homeland security and civil liberties, would once again be in conflict as it was during the Civil War.

As we were during Lincoln’s era, we are once again a nation at war and the laws of war are different. I know that this is a difficult concept to grasp, because most people today are not used to thinking in terms of wartime and peacetime. But in reality, the laws of war ARE different.

Think about this: our country lost 750,000 people over the four years of the Civil War. We could lose that many people in one day if we were attacked by terrorists using a chemical, biological or other weapon of mass destruction.

In his 1991 Pulitzer-prize winning book, The Fate of Liberty, historian Mark E. Neely, Jr., closes by admitting: “If a situation were to arise again in the United States when the writ of habeas corpus were suspended, government would probably be as ill-prepared to define the legal situation as it was in 1861. The clearest lesson is that there is no clear lesson in the Civil War – no neat precedents, no ground rules, no map. War and its effect on civil liberties remains a frightening unknown.”

Neely’s point is well taken today – since September 11, 2001, many scholars and citizens have questioned how President Bush’s reactions and actions to the problems of national security and war have on his legacy and civil liberties. President Obama was, in part, elected for his promises to change those policies. He was unable to realize his goals laid out in 2008, and incorporated some of President Bush’s reasoning into his own.

While “it is encouraging to know that this nation has endured such troubles before and survived them,” measures regarded as severe in Lincoln’s time seem mild when compared to those of ISIS, Osama Bin Laden or Saddam Hussein.

After Osama Bin Laden and his forces of Al Qaeda admitted to master-minding the horror that was September 11th, hundreds of suspected Al Qaeda and Taliban associates, not U.S. citizens, were arrested and detained in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as “enemy combatants.” President Bush proposed the use of military tribunals to try those individuals charged with terrorism. Such commissions do not enforce national laws, but a body of international law that has evolved over the centuries.

Our soldiers are required to follow certain guidelines, most simply stated to be the “rules of war.” General Order Number 100, or the Lieber Code, was issued by Abraham Lincoln to define the requirements by which U.S. soldiers were to conduct themselves during wartime. The Lieber Code was the basis for the Geneva Convention and the genesis of the Hague declarations.

During the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln also declared martial law and authorized such forums to try terrorists because military tribunals had the capacity to act quickly; to gather intelligence through interrogation; and to prevent confidential lifesaving information from becoming public.

During Lincoln’s time, the Union Army conducted at least 4,300 trials of U.S. citizens by military commission, which reflected the disorder of the time. Lincoln answered his critics with a reasoned, constitutional argument. A national crisis existed and in the interest of self-preservation he had to act. At the same time, he realized Congress had the ultimate responsibility to pass judgment on the measures he had taken.

These confounding problems remind me of the burglar who, while robbing a home, heard someone say, “Jesus is watching you.” To his relief, he realizes it is just a parrot mimicking something it had heard.

The burglar asked the parrot, “What’s your name?” The parrot says, “Moses.”

The burglar goes on to ask, “What kind of person names their parrot Moses?”

The parrot replies, “The same kind of person that names his Rottweiler Jesus.”

Our culture and nation are confronting many Rottweilers

Today’s commissions are composed of military personnel or civilians who are commissioned sitting as both trier of fact and law. Initially, any evidence may be admitted as long as, according to a reasonable person, it will have probative value. The defendant is entitled to a presumption of innocence and must be convicted beyond a reasonable doubt. Only 2/3rds of the panel, however, is needed to convict. Now, the Uniform Code of Military Justice lays out these rights and protects the due process rights of enemy combatants as it does for members of the country’s armed forces.

During the Bush Administration, I was chosen to be one of five civilians who sat on the Military Commissions Review Panel. This panel was charged with reviewing cases that went before us and determining whether or not a material error of law has occurred. Upon a finding of such error, the panel could return the case for further proceedings, including dismissal of the charges. Appeals were able to be made to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals as a right and by writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When a case came before us we had the option of granting the parties oral arguments. The other panel members and I believed in hearings and briefs for these appeals. We addressed important issues and we wanted everyone involved to have a full and fair opportunity to present their case. We were required to issue written opinions upon making a decision in these cases.

Like Lincoln’s critics during the Civil War, many have expressed their concern about the modern use of military tribunals.

Today, the issue of whether or not military tribunals should exist is simply one layer of this complex debate. The Bush administration did not do a good job explaining the law of war, the process of the military commissions, and the differences between civil liberties during wartime versus peacetime. The public is used to our regular system of dispensing timely and even handed justice through the courts. However, the laws of war are different from those we have come to understand.

It is not clear whether the 9/11 terrorists and detainees apprehended in the United States or abroad, are protected under America’s criminal justice system. Initially, President Bush proposed that those detained as enemy combatants would neither be protected by the international law of war or the four Geneva Conventions. However, he reversed himself when many countries indicated that if detainees would not be entitled to the Geneva Convention protections, they would be hesitant to turn over any alleged terrorists in their custody. President Bush argued that he, as the commander-in-chief, has the prerogative to choose in which forum captured enemy combatants could be tried.

Furthermore, our own Department of Defense indicated that if this country refused to apply the international law protections, Bush would have put U.S. troops in Afghanistan and Iraq, at risk if they were captured. Afghanistan and other unfriendly countries would likely refuse to apply such protections as well. These rights, protected by the Geneva Convention, govern the humane treatment of prisoners of war, include the prohibition of murder, torture, and mutilation.

To address some of the confusion, the Pentagon issued regulations to govern tribunals. Under Military Commission Order No. 1, issued in March 2002, the Secretary of Defense was vested with the power to “issue orders from time to time appointing one or more military commissions to try individuals subject to the President’s Military Order and appointing any other personnel necessary to facilitate such trials.”

Despite efforts to clearly regulate the parameters of these tribunals, criticism has remained. A New York Times editorial issued after the establishment of these regulations, noted that despite the fact that the idea of military tribunals for suspected terrorists is less troubling than it was at inception, “there is still no practical or legal justification for having the tribunals. The United States has a criminal justice system that is a model for the rest of the world. There is no reason to scrap it in these cases.”

The rebuttal to this argument has been that with over 90 million civil and criminal cases in our justice system each year, the federal courts may be ill-equipped to efficiently adjudicate terrorism cases. Unique issues like witness security, jury security, and preservation of intelligence have and will cause even more extraordinary delay.

So what is the best way to handle cases of those detained as enemy combatants? Who has jurisdiction over such matters – federal courts or military tribunals? Do United States citizens detained as enemy combatants warrant different protections than foreign detainees?

Actually, both have jurisdiction. The President may decide that military tribunals are an avenue for trial. Trials have also been held in U.S. District Courts as well. During the 2003 -2004 United State Supreme Court term, the Court agreed to consider three cases in which jurisdiction and authority over enemy combatants were at issue.

The Supreme Court first considered the case of Rasul v. Bush brought by foreign detainees captured abroad during the hostilities between the United States and the Taliban and detained at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

The detainees challenged their detention by filing petitions in the District Court for the District of Columbia. The District Court determined that because the petitioners were held outside of the United States, it did not have jurisdiction to hear their petitions. The Court of Appeals affirmed.

The United States Supreme Court granted petitioners’ writ of certiorari and after hearing arguments, opined that because petitioners were being held at an American Naval Base, over which the United States exercises “complete jurisdiction and control,” “aliens held at the base are entitled to invoke the federal courts’ authority,” by filing writs of habeas corpus.

The Supreme Court remanded the case to District Court, finding that it did indeed have jurisdiction over challenges made by foreigners relative to their indefinite detention in a facility under United States control.

The Court next heard arguments in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld. Unlike the petitioners in Rasul, Yassar Hamdi was an American citizen. He was fighting with the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001 when his unit surrendered to the Northern Alliance, with which American forces were aligned. He was held at a military brig in Charleston, South Carolina, for two years without being formally charged.

In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Hamdi challenged the government’s treatment of him as an “enemy combatant”. The Supreme Court held that due process requires that citizens detained in the United States be given a meaningful opportunity to contest their detention before a “neutral decisionmaker.”

The Court stated that the “neutral decisionmaker” could be either the federal judicial system or a military tribunal provided such tribunal allows him to challenge the factual basis for his detention. The burden is initially on the detainee. Hamdi had also asked the Supreme Court to find that the lower court erred by denying him immediate access to counsel after his detention and by disposing of the case without the benefit of counsel. The Justices found that because counsel had been appointed since their granting of certiorari, there was no need to decide the issue.

The Supreme Court was also presented with Padilla v. Rumsfeld. The petitioner, Jose Padilla was a United States citizen detained in a military brig in Charleston, South Carolina. He was being held as an enemy combatant. The threshold questions raised by the Padilla case were 1) whether he properly filed his petition in the proper court and 2) whether the President possessed the authority to detain Padilla militarily. Because the United States Supreme Court ruled that Padilla improperly named Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and filed his petition in the wrong jurisdiction, it did not reach the second issue regarding the President’s authority over this United States citizen accused of terrorism.

The decisions made by President Bush increasingly came under attack during his administration and even after the Supreme Court’s decisions in Hamdi and Rasul, the legal waters remain murky regarding citizens and noncitizens detained as enemy combatants.

Another case has wound its way up to the United States Supreme Court. In 2004, Federal District Court Judge Robertson heard the matter of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. Captured and originally detained in Afghanistan, Petitioner Hamdan was transferred to the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba. Hamdan challenged the government’s plans to try him in front of a military tribunal instead of before a court martial.

The District Court held that before a prisoner can be tried by a military tribunal, there must first be a hearing in order to first determine whether the terms of the Geneva Convention apply. If they do apply, then the defendant is entitled to have his case heard under the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the defendant would receive the same procedural safeguards as any American citizen.

A three judge panel of the U.S. Federal Appeals Court overturned the District Court ruling stating that the president does have the authority by the post-9/11 congressional legislation to establish military tribunals, try, and punish enemy combatants who have violated the laws of war. The panel court also held that the Geneva Convention does not apply to members of al Qaeda.

On November 10, 2005, the Senate voted to prevent captured “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo Bay the right to seek writs of habeas corpus. In an amendment sponsored by Senator Lindsey Graham, that was passed 49 to 42, Guantanamo detainees, non U.S. citizens, would have one appeal to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals at the conclusion of the military proceeding including review thereof if the sentence is ten or more years of imprisonment or death. But they would no longer have a right to the writ of habeas corpus. On January 11, 2006, President Bush signed the Detainee Treatment Act incorporating these provisions.

After that, the Supreme Court heard the appeal of Hamdan with Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., who was a member of the Circuit Court Panel, recused. Arguments were held in March 2006 and on June 29, 2006, the United States Supreme Court decided the case of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 126 S. Ct. 2749 (2006). In this 5 to 3 decision, the court ruled that President George W. Bush did not have the power or authority to create military tribunals in Guantanamo, but four of the justices indicated that the Congress could authorize the President and that is exactly what the Congress did. On October 17, President Bush signed the Military Commissions Act of 2006.

In 2008, the Supreme Court considered Boumediene v. Bush, in which several individuals imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay challenged congressional action denying them their ability to file a petition in federal court. In that case the Supreme Court held that, despite being labeled enemy combatants, the individuals are not prevented from petitioning the courts seeking a writ of habeas corpus.

These issues are more exacerbated today than during Lincoln’s time because of the ever shrinking global village in which we all live. During the Civil War, Lincoln was concerned about the war’s implications with Britain and France. Today people are even more acutely aware of how the United States is perceived by its citizens and our allies, especially on matters of human rights and freedom.

The length of the war we fight today is much different than the Civil War. The Civil War, despite its high cost in lives, only lasted four years. The war started today originated on September 11, 2001, meaning that these wars have lasted for more than sixteen years. Today, our nation has fought four times as long as we did in the Civil War. However, we are less aware of and exposed to the current war than citizens were during the Civil War. And that effects how we both feel and think about civil liberties with regards to war.

It is clear that the argument over Lincoln and civil liberties was as robust in his own time as in ours and deserves an equally careful reexamination by modern historians. That Lincoln emerges from the perennial controversy that afflicted his administration over civil liberties with a reputation for statesmanship may be the most powerful argument for his judicious application of executive authority during a national emergency.

Lincoln’s legacy is that of a great leader. Both President Bush and President Obama’s legacies have yet to fully take shape in the public’s eye. However, Lincoln’s words that the United States was “the last best hope of earth,” still resonate for survival of democracy in the world.

Lincoln’s success, I think can be distilled into four basic tenants. First, Lincoln was clear and confident in his belief that everyone should have an equal chance in the race of life – devoid of tyranny and terrorism. So strong was his conviction that he was willing to challenge the political hierarchy, in order to attain that goal. And people resist change.

Lincoln’s actions drew swift and severe disapproval. But, in-keeping with the second tenant of leadership, he held true to his principles, remaining steadfast even in the face of criticism. Lincoln’s critics did not confine their attacks to his professional decision making. He also suffered continuous assaults on his personal character. Lincoln’s height (6’4’’) and long arms led newspapermen to label him a “baboon,” a “gorilla,” the “Illinois beast,” and “Abraham Africanus I” for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. He was called a “political coward,” “timid and ignorant,” “pitiable,” and “two faced.” Lincoln responded to the latter by saying, “if I had another face would I use this one?”

The third leadership quality that Lincoln possessed was the significance he placed on nobility, honor and character — in himself and in others. He so eloquently professed this element of his leadership philosophy in one sentence, “I desire so to conduct the affairs of this administration that if at the end, when I come to lay down the reins of power, I have lost every other friend on earth, I shall at least have one friend left, and that friend shall be down inside me.”

And finally, the characteristic that perhaps best evidences Lincoln’s leadership, was his ability to thrive in the midst of the fray and in the midst of a noble crusade – a focused pursuit of justice.

As the following story shows, Lincoln was sometimes too consumed by this noble pursuit.

The trial was proceeding poorly for Melissa Goings, charged with murdering her husband. Her attorney, Abraham Lincoln, called for a recess to confer with his client, and he led her from the courtroom.

When court reconvened, and Mrs. Goings could not be found, Lincoln was accused of advising her to flee, a charge he vehemently denied. He explained however, that the defendant had asked him where she could get a drink of water, and he had pointed out that Tennessee had darn good water! She was never seen again in Illinois! Rough justice to be sure.

The point of the story is that when we judge history or historic individuals, we need to look at the events and the persons within the context of the times in which the events occurred and the individuals lived — and not through the wrong end of the telescope.

From time out of mind, warriors have been asked to lay down their bodies, their lives, on the martial altar. Modern wars have also visited agonies of deprivation on civilian populations.

In a total war like World War II, the lines between battle front and home front blurred, compelling far-reaching economic mobilizations and requiring civilian moral and material support – not to mention political approval – to maintain a fighting force in the field.

War leaders have long understood the utility of nurturing the feeling that “we’re all in this together,” combatant and noncombatant alike, whether the privations on the home front were truly necessary or not. The sentiment of shared sacrifice binds soldier to civilian. For better or worse, that sentiment is what has made successful modern warfare possible.

During the Vietnam War, the Lyndon Johnson Administration scarcely dared ask the affluence – intoxicated American public to share even a modicum of the afflictions endured by the troops in Asia.

The contrast between the country’s sorry experience in Vietnam and its achievement in World War II suggests that some measure of civilian sacrifice, illusory or not, may be necessary to sustain the will to go the bitter distance in the war on terror.

Lincoln’s wartime decisions raised the really tough issue that many continue to evade: When should we give up some liberties in the name of security?

There are times when dangers are so immediate and so terrifying that we do need to sacrifice some freedoms to stop them. And the Civil War was one of those times. For sixteen years we as a nation have tried to balance the objectives of both individual liberty and national security. All of us need to continue thinking and talking about when we would give up some liberties to save the Union today. If we faced a rash of suicide bombers striking several American cities at the same time, how much would our national conversation change? Worse yet, how would our conversation change if a “dirty bomb,” nuclear attack, small pox or anthrax attack occurred? It is only through discussion today that we can perfectly-or-imperfectly-ensure that we balance these two objectives as best we can—and as Lincoln did.

In his message to Congress in 1862, Lincoln addressed the pressures of protecting civil liberties and the nation. His words are as applicable today as they were 155 years ago. He wrote to Congress addressing his “remunerative emancipation” plan. Lincoln’s plan called for the payment of slave owners in return for their slaves’ release. Lincoln told Congress the following:

“Is it doubted, then, that the plan I propose, if adopted, would shorten the war, and thus lessen its expenditure of money and of blood? Is it doubted that it would restore the national authority and national prosperity, and perpetuate both indefinitely? Is it doubted that we here—Congress and Executive—can secure its adoption? Will not the good people respond to a united, and earnest appeal from us? Can we, can they, by any other means, so certainly, or so speedily, assure these vital objects? We can succeed only by concert. It is not “can any of us imagine better?” but “can we all do better?” Object whatsoever is possible, still the question recurs, “can we do better?” The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must dis-enthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

Hon. Frank J. Williams is the founding Chair of The Lincoln Forum and the retired Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court. He teaches at the U.S. Naval War College and serves as a mediator and arbitrator. In 2003, he was appointed a judge of the U.C. Court of Military Commissions to hear appeals from enemy Combatants at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.