The Debate Over the Debates: How Lincoln and Douglas Wages a Campaign For History

By Harold Holzer

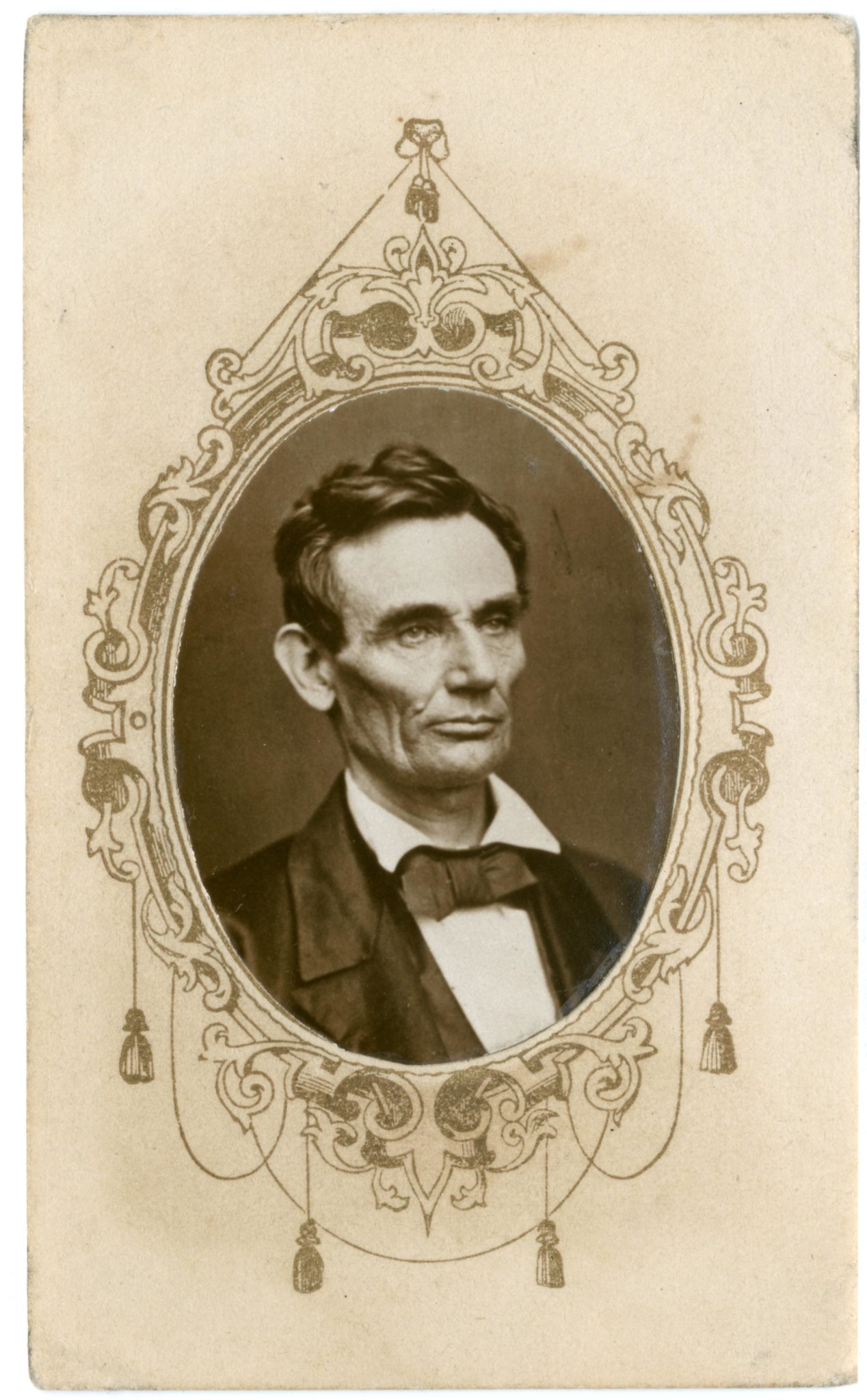

As most readers of 19th-century history know, the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates sparked an explosion of public interest in Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas, and the sport of political debating itself. The encounters not only riveted the tens of thousands of eyewitnesses who packed Illinois town squares and fairgrounds to hear them, but also captivated the hundreds of thousands more around the country who devoured every word of their arguments in the newspapers.

Often forgotten, however, is that what these readers got to examine in 1858 depended very much on the political party with which they (and their favorite newspapers) were affiliated. And what Democrats and Republicans saw was quite different. In the age of Lincoln and Douglas, Republicans read Republican-affiliated papers, while Democrats read pro-Democratic journals. And the politically slanted debate coverage each published differed so markedly they seemed to be reporting entirely different events. The reprinted debate transcripts varied dramatically as well, recorded on the spot, but with entirely different results, by separate stenographers hired by Chicago’s pro-Republican and pro-Democratic dailies.

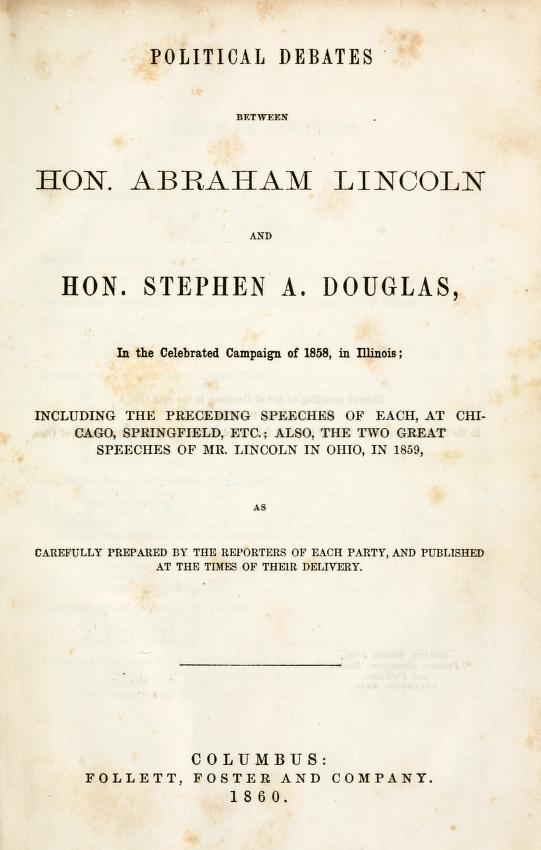

The debates have been re-published many times since 1858. But following their initial appearance in book form in 1860, they have almost always featured the Republican newspaper versions of Lincoln’s remarks, and the Democratic reprints of Douglas’s, just as they were first transcribed for, edited by, and issued in, the pro-Republican Chicago Press and Tribune and the pro-Democratic Chicago Daily Times, respectively.[1] For a century and a half, most readers have relied on, accepted, and cited these “official” party transcriptions even though they were undoubtedly burnished before their initial appearance in newsprints.[2] How they came to be permanently enshrined in book form constitutes a compelling story in itself.

The actual debates proved unrestrained, highly entertaining, if not always eloquent free-for-alls. They seem even more so in their ori

ginal, unedited, unvarnished, and seldom-reissued form—that is, the way opposition stenographers recorded them on the scene—sans editorial amelioration—even if it might reasonably be argued that a Republican stenographer might as easily misreport a Democratic speech as a loyal Democrat might mangle a Republican one.

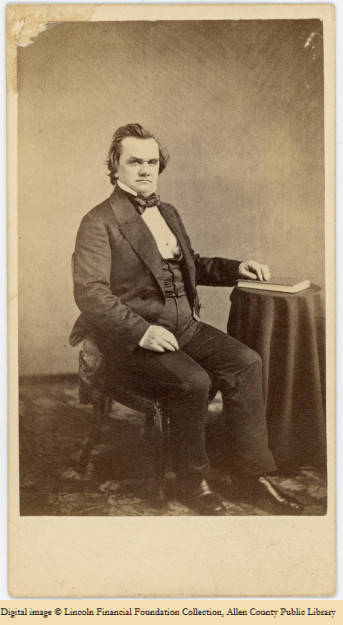

Even as the debates progressed, a secondary debate erupted over these partisan transcripts. The Republican press charged that Democratic reprints garbled Lincoln’s utterances and refined Douglas’s. The Democratic press unleashed similar attacks on Republican iterations. By way of example, the Chicago Times insisted that the Tribune was guilty not only of shamelessly marring “The Little Giant’s” debate speeches, but of “re-writing and polishing the speeches of…poor Lincoln,” who, it taunted, “requires some such advantage.” The Tribune countered that Times mutilations left Lincoln’s actual words so “shamefully and outrageously…emasculated” that if doctoring prose became a crime, “the scamp whom Douglas hires to report Lincoln’s speeches would be a ripe subject for the Penitentiary.”[3]

The still-relevant issue—the accuracy of the debate transcripts we generally accept—remains unresolved to this day. But it was Lincoln, loser of the campaign for the U. S. Senate in 1858, who subsequently won the campaign over how posterity remembers them. Stung as he was by his defeat—and with it, the implicit rejection of his debate arguments—Lincoln within weeks grew “desirous of preserving in some permanent form, the late joint discussions between Douglas and myself.”[4] With no private secretary to help him, he proceeded to purchase “a book binder to paste the speeches in consecutive order,” obtained two sets of the complete run of transcripts from both the Tribune and Times (in case some transcripts appeared on back-to-back pages), and in short order began cutting them out and neatly gluing them in his new “Scrap-book.”[5]

It was Lincoln who determined to use the Republican versions of his transcripts, and the Democratic record of his opponent’s. Adopting these authorized, party-sanctioned printings, he reasoned, “would represent each of us, as reported by his own friends, and thus be mutual, and fair.” But he did proceed to make minor corrections to his own remarks, offering Douglas the opportunity to correct typographical errors in his, if he so desired. Twisting the knife a bit, Lincoln left no doubt that he believed he had more of a right to make editorial changes than did his rival, explaining somewhat dubiously: “I had no reporter of my own, but depended on a very excellent one sent by the Press & Tribune, but who never waited to show me his notes or manuscripts.”[6] Even a pro-Lincoln man would have been forced to admit that Douglas had enjoyed no more time to review and amend his speeches immediately after their delivery than had Lincoln.

Still, it was Lincoln who seized the initiative to republish the debate; Lincoln who cannily realized that they might yet help him in future endeavors by further circulating his verbal battles with a national figure as prominent as Senator Douglas. At first, Lincoln elicited no interest in the project from publishers, but during a barnstorming tour through Ohio in 1859, found a buyer through a fortuitous accident. Apparently he had taken the bulky scrapbook along with him (no doubt hoping to attract interest along the way), then carelessly left it behind one day in his hotel room. In making inquiries to secure its safe return, he intrigued a local Republican leader who thought it might impress the Columbus publishers Follett, Foster & Co. It did. The book appeared under their imprint just before the 1860 race for president got underway. And it became so successful that it served almost to campaign nationally in Lincoln’s behalf in an age in which presidential candidates did no campaigning on their own.[7] The book sold 30,000 copies in the spring and summer of 1860.

Douglas was not grateful. As far as his camp was concerned, the re-publication of the transcripts only reinvigorated the 1858 debate over their accuracy, a matter he clearly felt remained unresolved. Moreover, Douglas may well have feared that a new edition could remind Southern voters that, during the debates, Lincoln had cornered him into conceding the right of a local jurisdiction to ban, as well as welcome, slavery. Choosing to cast doubts about the book before it appeared, the Democratic press charged that Lincoln had unfairly re-edited his “manuscripts” while denying the same privilege to his once and current foe.

James W. Sheahan, editor of the pro-Douglas Chicago Times, wrote provocatively to Lincoln in late January 1860: “I see it stated that you have furnished some gentlemen of your party in Ohio with revised copies of your speeches [emphasis added].” To this sly insult Sheahan added a long-overlooked, veiled threat to outrace Lincoln for their reissue. “I am about publishing a book,” Sheahan warned. “In it I propose to include one or more, possibly all of your speeches delivered in the joint discussions between Judge Douglas & yourself.”[8] Sheahan was in fact preparing only a campaign biography of Douglas, but Lincoln had no way of knowing that, and ample reason to think the Times might rush forward a pre-emptive rival book. Lincoln refused to cooperate, telling Sheahan he had “no copies” of his speeches “now at my control” to provide the Times, true enough, having sent his only set to Follett & Foster; but he made no offer to secure additional copies. “You labor under a mistake, somewhat injurious to me,” Lincoln further informed Sheahan, “if you suppose I have revised the speeches, in any just sense of the word. I only made some small verbal corrections, mostly such as an intelligent reader would make for himself, not feeling justified to do more.” Perhaps worried about the Democratic attack, Lincoln decided to codify that very argument in the preface to the actual book, steadfastly maintaining that its contents were “reported and printed, by the respective friends of Senator Douglas and myself, at the time—that is, his by his friends, and mine by mine. It would be an unwarranted liberty,” the prologue rather self-righteously maintained, “for us to change a word or a letter in his, and the changes I have made in mine…are verbal only, and very few in number.”[9]

The Follett & Foster project went forward, with no sign of a competing volume from the Douglas camp. Feeling exposed, Douglas predicted that the permanent record collected by Lincoln would be “partial and unfair,” with Lincoln’s speeches “revised, corrected, and improved,” and his own, “ambiguous, incoherent, and unintelligible.” Lincoln’s entire project, Douglas bristled, constituted an “injustice.”[10]

Unjust it well might have been for Lincoln to publish his debates scrapbook without Douglas’s review and permission. But it was also a brilliant political and public relations strike, all the more remarkable because Lincoln conceived it when allegedly wallowing in melancholy after coming up short on Election Day 1858.

Lincoln had lost that election, but “won” the debates in part because he provided the source material for all subsequent book versions through 1993. The debates came down to us not as they were originally argued in the seven towns that hosted them in 1858, but as Lincoln wanted his own—and succeeding—generations to remember them, beginning with voters in the presidential campaign of 1860. It is no surprise that most readers and writers still believe, as James M. McPherson once put it, that Lincoln won the debates “in the judgment of history—or at least of most historians.”[11]

Harold Holzer is Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. His next book is Monument Man, a biography of Lincoln Memorial Sculptor Daniel Chester French

[1] An intentional exception was my book, The Real Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The Complete, Unexpurgated Text (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), which printed the “opposition transcripts”—Democratic versions of Lincoln’s remarks, and Republican versions of Douglas’s.

[2] Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin, Rude Republic: Americans and their Politics in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 163. The authors note that “urgent partisan rhetoric” was “a staple of the political press.

[3] Chicago Times, October 12, 1858; Chicago Press & Tribune, October 11, 1858.

[4] Lincoln to Henry Clay Whitney, November 30, 1858, in Roy P. Basler, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-1955), 3:343.

[5] To Charles H. Ray, November 30, 1858; to Henry Clay Whitney, December 25, 1858, Collected Works, 3:341, 347

[6] Lincoln to William A. Ross, March 26, 1859, Collected Works, 3:373.

[7] Douglas defied tradition by speaking in public in the South, and was roundly mocked for the effort.

[8] Sheahan to Lincoln, January 21, 1860. Sheahan was intentionally imprecise here; he was not actually contemplating a rival edition of the debates, but working on a campaign biography of Douglas, not only a fellow Democrat but an investor in the paper.

[9] Lincoln to James W. Sheahan, January 24, 1860, Collected Works, 3:515.

[10] Robert W. Johannsen, ed., The Letters of Stephen A. Douglas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961), 489.

[11] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 187.