Young Lincoln and the Ohio

While in the White House, Abraham Lincoln described for Secretary of State William Seward one key experience connected with the Ohio River near Troy, Indiana. Lincoln recalled that he was asked by two travelers to scull them out to a passing river steamer. After they and their trunks were on board the steamer, each man threw a silver half dollar on the bottom of Lincoln’s little boat. Lincoln told Seward,

I could scarcely believe my eyes. . . . You may think it was a very little thing, but it was a most important incident in my life. I could scarcely believe that I, a poor boy, had earned a dollar in less than a day. The world seemed wider and fairer before me. I was a more hopeful and confident being from that time.1

Although this incident is only one during Lincoln’s Indiana years, the Ohio River clearly made his “world seem wider and fairer.”

No doubt the boy Lincoln heard his father recall stories of his 1806 flatboat trip to New Orleans. Likely with great anticipation did seven-year-old Abraham first see the Ohio in December 1816 less than two miles from Troy, Indiana. More than simply a geographic feature, the Ohio demarked an old America from a new America.

Describing the Lincolns’ 1816 move to Indiana, President Lincoln said, “This removal was partly on account of slavery; but chiefly on account of the difficulty in land titles in [Kentucky].”2 North of the river, law prohibited slavery. A farmer and craftsman like Thomas Lincoln, therefore, need not compete with skilled slaves for work or be controlled by a slaveholding class. Here he also was free from antiquated land survey and recording procedures that denied security in land holdings. North of the Ohio all land was owned and surveyed by the United States government, thus assuring a clear title to a farm. Thomas Lincoln obtained such a land patent to eighty acres in Indiana.

Although for their homestead the Lincolns chose land some seventeen miles from the river, frequently they traveled to river towns like Troy and Rockport, Indiana, to tend to legal affairs, visit the post office, and conduct other business. By the late 1820s, the river offered young Abraham opportunities for work. For a while, Dennis Hanks, Squire Hall, and Lincoln all worked to cut firewood for fuel-hungry steamboats on the Ohio. Later, James Taylor at Troy hired Abraham to do farm work, help butcher hogs, and operate a ferry over the Anderson River where it flowed into the Ohio.3

For Lincoln, though, the chance to learn about the world proved perhaps a greater reward than money he earned. Here he met travelers from all over the country, indeed all over the world. The Ohio constituted the interstate highway of the day, connecting the Indiana wilderness to a wider world. Doubtless young Lincoln interrogated travelers about politics, current events, and the state of the country. Along with learning directly from travelers, he read newspapers carried by those passengers traveling up and down the river—both familiar newspapers from New Orleans to Pittsburgh and those less familiar ones printed in New York and other eastern cities.

Furthermore, the Ohio River acquainted Lincoln with the nation’s emerging market economy. By the late 1820s, local farmers began moving from subsistence farming to surplus production, meaning they could sell or barter for items they could not provide for themselves. Merchants who acquired these surplus items—in the Lincoln community that was James Gentry—transported them to a larger market. The river, then, provided both transport and markets.

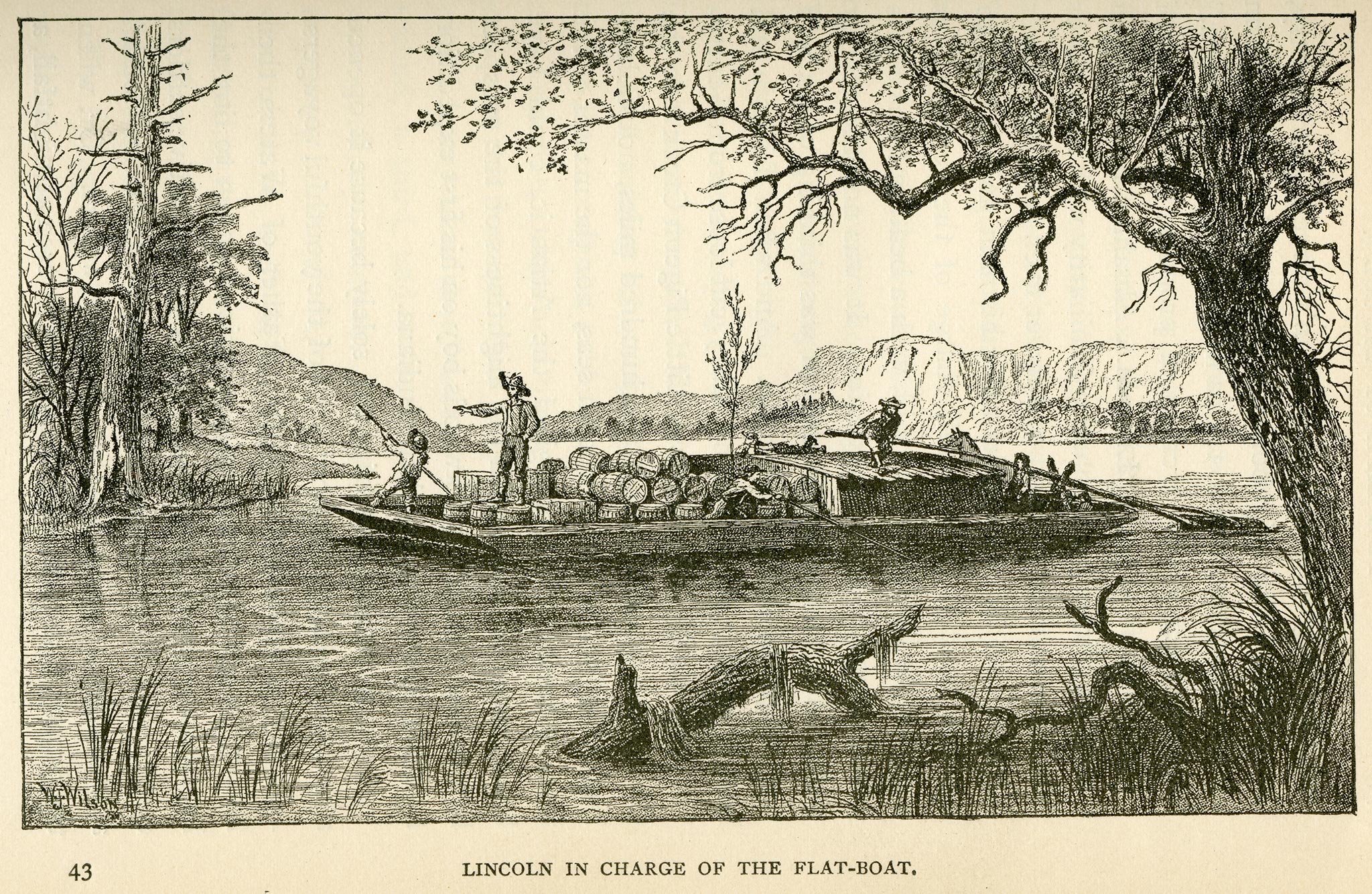

Abraham Lincoln’s best-known connection with the Ohio River was his 1828 flatboat trip. James Gentry hired his son Allen and Lincoln to take a flatboat-load of produce—probably grain, pork, lard, and fowl—to markets down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Though most authors contend this trip’s main value lay in Lincoln’s first observing plantation slavery and seeing a slave auction, I perceive a more compelling element to the trip.

For the first time, Lincoln assumed significant responsibility, and he performed well. He was only nineteen; Allen Gentry was twenty-one. These two young men guided the flatboat around sandbars, tree snags, eddies, and a river crowded with steamboats; and they guarded against ruthless river pirates along the way. Along the lower Mississippi, they negotiated to sell produce at various plantations. Finally, in New Orleans they sold their remaining cargo and the boat itself. These tasks were hardly easy, even for more experienced men.

This flatboat adventure proved one of the most significant experiences of Lincoln’s life between 1816 and 1830. He saw sights and situations vastly different from those familiar in Kentucky and Indiana. He witnessed large-scale plantation farming, he heard languages foreign to him spoken by persons of diverse nationalities, he saw architecture unknown in Spencer County—in short, Lincoln experienced a whole new culture.4 Truly, Lincoln “. . . was a more hopeful and confident being” because of his Ohio River experiences.

Bill Bartelt is author of There I Grew Up: Remembering Abraham Lincoln’s Indiana Youth (2008) and a Director of Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana. This material was presented at the Lincoln Symposium at the Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, Indiana, in November 2016.

* * *

- J. G. Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, Mass.: Gurdon Bill, 1866), pp. 33-34.

- Abraham Lincoln, “Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps,” in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 4 (New Brunswick, N. J.: Rutgers UP, 1953-55), pp. 61-62.

- Louis Warren, Lincoln’s Youth: Indiana Years Seven to Twenty-one, 1816-1830 (New York: Appleton, Century, Crofts, 1959), pp.144-145.

- Jason Silverman, Lincoln and the Immigrant (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), p. 13.