THE CONCISE LINCOLN LIBRARY of Southern Illinois University Press

THE CONCISE LINCOLN LIBRARY of Southern Illinois University Press

by Sylvia Frank Rodrigue

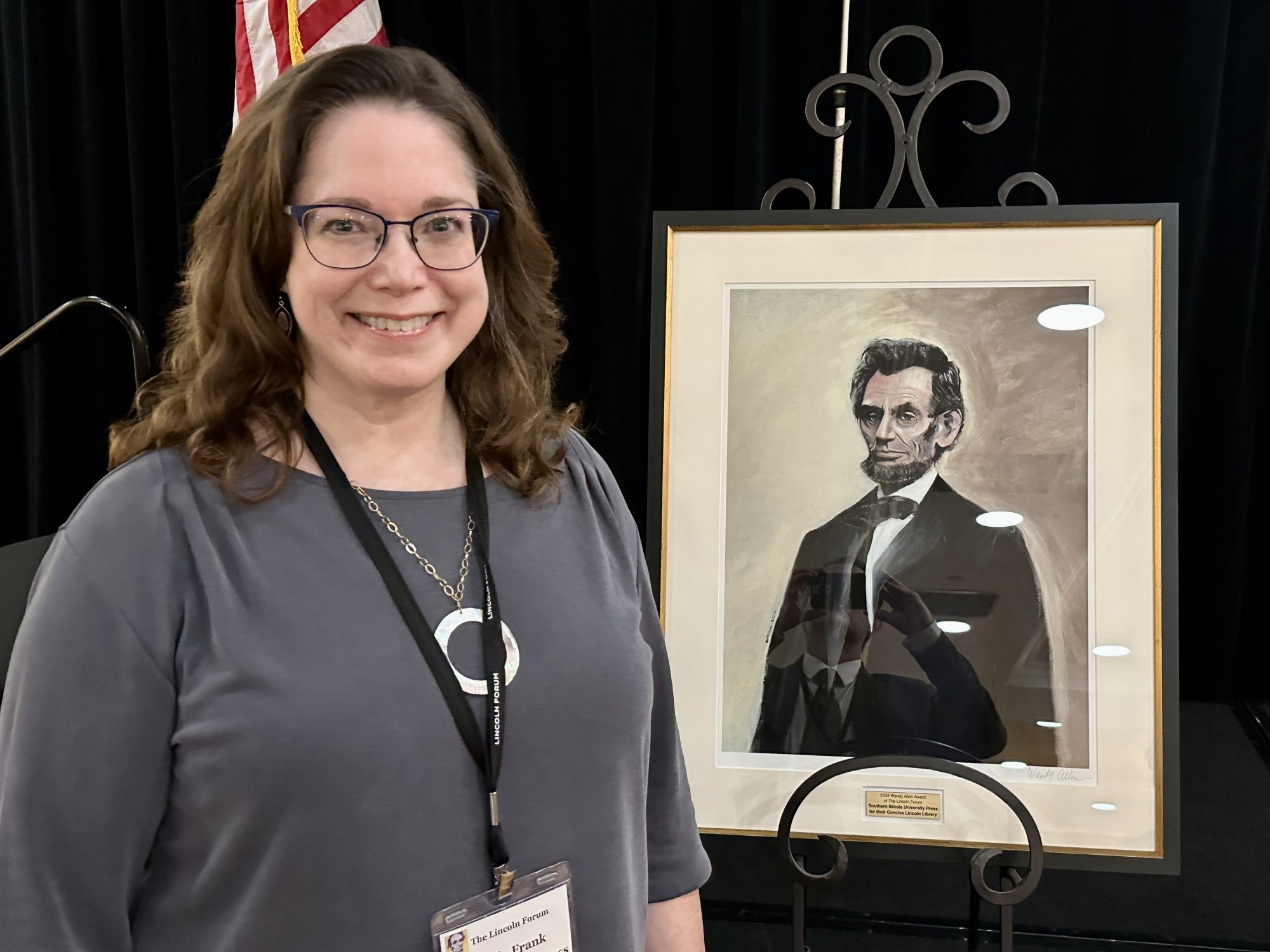

At its meeting in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in November 2023, Jonathan White—editor of Lincoln Lore and vice chairman of The Lincoln Forum—announced that the annual Wendy Allen Award, which honors institutions or organizations that have “achieved widespread recognition for bringing learning, scholarship, and enlightenment to a wide public,” would go to Southern Illinois University Press in recognition of the Concise Lincoln Library. Further, he announced, the Forum would grant honorary Harold Holzer Lincoln Forum Book Prizes to the series co-editors. It was the culmination of a journey that had started fifteen years earlier, from the spark of an idea in early 2008 to the publication of twenty-eight short accessible books about the life, times, and legacies of Abraham Lincoln.

The book series was conceived after Richard W. “Dick” Etulain, an eminently accomplished historian of the American West, and I started working together on his edited book, Lincoln Looks West: From the Mississippi to the Pacific (2010). We discussed other possibilities, such as a series of edited essay collections on Lincoln. When Dick learned about Jason Emerson’s short book Lincoln the Inventor (2009), the project sparked an idea, and Dick promised to send me a list of other Lincoln topics that would be appropriate for a brief format.

The thought of a short-book series held great appeal for my colleagues at SIU Press. But Dick expressed some reservations about becoming the editor of another book series. He had retired from teaching at the University of New Mexico; perhaps a younger scholar who had access to university resources such as phone, mail, and travel money would be a better choice. A western historian—not a Lincoln scholar—Dick had already edited six other book series, including the Western Biography Series (University of Oklahoma Press) and The American West (University of Nebraska Press).

The SIU Press director at the time, Lain Adkins, and I knew Dick to be an excellent historian and outstanding writer, and we very much appreciated Dick’s experience as a book series editor. A person has to be amiable as well as organized and detail-oriented in order to have edited several successful book series. Perhaps having an outsider’s view on the Lincoln field—albeit one who is well versed on all things Lincoln—would be useful for authors and the Press.

As my colleagues and I discussed the series editorship, we agreed that we wanted the authors and topics to be the main draws for potential readers. It was possible that having a famous Lincoln historian as series editor might overshadow the other authors in the series. Given all the positives we saw, to us it made sense to sign up a historian familiar with Lincoln who wrote well and was adept at helping other scholars perfect their manuscripts. Therefore, we chose Dick Etulain as series editor.

Book series thrive when they are informed by great collaboration among editors. Our top series co-editor pick was another person who had extensive Lincoln knowledge and outstanding editing experience: Sara Vaughn Gabbard, then the editor of Lincoln Lore. Under her tenure, Lincoln Lore was twice named one of the top fifty magazines in the country by the Chicago Tribune.

Sara and I had started working together three years earlier on the essay collection Lincoln and Freedom: Slavery, Emancipation, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2007), which she coedited with Harold Holzer. The essay collection Lincoln’s America, 1809-1865 (2008), which she coedited with Joseph R. Fornieri, soon followed. Sara possessed a keen editorial eye, a penchant for meeting deadlines, as well as a wealth of knowledge about Lincoln and those who study him and his legacies. She worked as the development director at The Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne, Indiana, but this was around the time it was slated to close. Maybe, we thought, she would be open to starting a new project. To our joy, she was.

Next, I introduced Dick and Sara by email, and the three of us wrote and refined a book series proposal. Our “Lincoln Brief Book Series” proposal pointed out the need for short books on Lincoln to counterbalance the very long ones released every year. It was hard to find well-researched, well-written books on Lincoln that were fewer than 250 pages, and we thought there would be a market for people who want to learn more about Lincoln but don’t have the time to read long tomes. As we wrote in the proposal, we hoped to publish two types of books: “(1) those that deal with well-known subjects in a fresh way; and (2) those that uncover a new Lincoln subject previous historians or biographers have not treated.”

Any good book proposal includes short biographies of the people involved. Our series proposal contained three series editor bios, because Dick and Sara had decided I should be named an official series coeditor. I had been instrumental in putting together the series, they noted, and I would be important in keeping it running. Though not a scholar, I had gained a familiarity with the topic through my work acquiring Lincoln books, including a new edition of The Lincoln Family Album (1990; SIU Press edition, 2006) by Mark E. Neely Jr. and Harold Holzer, and The Madness of Mary Lincoln (2007) by Jason Emerson. I was astounded and honored, for, as far as I knew, it was unheard of for a university press acquisitions editor to serve as a series editor. But working in an unusual insider-outsider role made such an opportunity possible for me. I am not an SIU Press staff member. I am an independent contractor, working as a freelance acquisitions editor. The Press director agreed. A colleague asked me whether being a series editor would mean that I would try to rush through books that might not be ready in order to meet publication quotas. My point of view was the opposite: if a book has my name on it, I want to make certain that the manuscript is as strong as it can be—even if it is late.

Our hopes were high. Lain wanted to publish split runs, releasing both cloth and paperback copies at the same time. Format decisions are challenging, particularly when creating a new series. Who is the audience? How many copies can we sell? Many aspects of publishing are an art, not a science, and publishers sometimes bemoan the lack of a crystal ball. The thinking was that hardcover books would appeal to Civil War enthusiasts and libraries and paperbacks would appeal to students and people at gift shops at museums and parks. A series purchase from a chain bookstore seemed like a strong possibility. Lain thought we might see cardboard stands filled with SIU Press Lincoln books in bookstores throughout the country.

We had moved quickly in these early stages, and in May 2008 I presented the project to the SIU Press Editorial Board. The members approved the proposal.

Next we had to settle on a series title for what we’d been referring to as “Little Lincolns.” Coming up with the right title for a series or book can be extremely difficult. A title is a marketing tool, and publishers always want titles that will appeal to the target audience. Dick, Sara, and I brainstormed. Among the titles we considered and discarded were Lincoln Connections, Lincoln Stories, Lincoln: Life and Legacies, Focus on Lincoln, Concise Lincoln Readers, Lincoln Redefined, and America’s Lincoln: The Concise Library.

It took several weeks for the key people at SIU Press—Director Lain Adkins, Marketing Manager Jennifer Fandel, Acting Editor-in-Chief Karl Kageff, and Editorial, Design, and Production Manager Barb Martin—to agree on a title the series editors liked, too. Some of us liked the strong ring of “America’s Lincoln” and how it immediately placed Lincoln in context, but it seemed a subtitle would be necessary if we went with that option. Eventually, and despite an objection that the word concise is not very exciting, everyone voted for “The Concise Lincoln Library.” We liked how the title hints at the idea that history book collectors would buy all the books in the Concise Lincoln Library (CLL) for their own libraries.

How would the books look? We debated the options and decided we wanted crisp, clean designs. The length should be between 30,000 and 50,000 words, about 128 to 176 book pages, with no more than 10 images. The series trim size would be 5 x 8 inches.

Cover design generated much discussion. Choosing book cover designs is a point in the publication process that can be challenging, even contentious, as different staff members bring strong viewpoints to their evaluation of how a book should look. For a series, the stakes are higher. Should all the books look the same? Should they each have different cover designs? Each option has merits. In the end, talented SIU Press designer Mary Rohrer created the top hat series logo and created the cover design. The Press commissioned the amazing Gettysburg-based artist Wendy Allen to paint a profile view of Lincoln that would fit Mary’s design. Future designers would be able to change out the background colors for each book. Not having to create a new design for each book would save time and eliminate a potential roadblock in the publishing process.

Perhaps the greatest benefit of publishing with a university press is the opportunity for an author’s work to undergo peer review, in which anonymous experts provide pre-publication feedback to strengthen manuscripts. Dick, Sara, and I talked about how the peer review process would work with three series coeditors. For each project I would convey to the author my own memo along with three reports: one from an anonymous peer reviewer and one each from Dick and Sara.

We followed this plan for each project save one—Lincoln and Reconstruction (2013), written by my husband, John C. Rodrigue. It was Sara who, upon editing John’s Lincoln Lore article, thought that he was such a good writer that he should be in the series, regardless of his connection to one of the editors. I recused myself, and Karl Kageff acquired John’s book.

Next came the work of commissioning authors to write for the series. Sara suggested a series sponsorship to pay CLL authors, since as a nonprofit SIU Press has no money for advances against royalties or to cover the costs of permissions, illustrations, and indexing. Having a way to pay authors would be especially useful in attracting those people who usually published with more well-heeled, for-profit publishers. We decided it would be ideal to have a three-year grant that would cover twelve books, four per year. Soon Sara secured a donation from the Leland E. and LaRita R. Boren Trust to pay authors. When the SIU Press Editorial Board approved an advance contract, authors would receive a signing bonus. They would receive either a second signing bonus upon Editorial Board approval of the final manuscript or a free, professional index. Some CLL authors chose to create their own indexes and take the second signing bonus, but most used the money to pay for an index. The Boren Trust sent three donations over three years—enough, we believed, for twenty-five authors.

It was surprisingly easy, compared to other acquisitions work, to line up CLL authors and topics. The combination of authors’ interest in their topics and the concise nature of the manuscripts must have been the keys—though I’m sure the signing bonus helped, too. By the Lincoln Bicentennial in 2009 we had commissioned twelve books, and in early 2010, the first manuscripts started to arrive. Given how long most books take to write, to have manuscripts within eighteen to twenty months of an advance contract felt extraordinary.

Having manuscripts in hand brought up new issues for consideration, including how we would handle the need to show the research that underpinned these short books. The series coeditors and press staff discussed historiography, citations, bibliographies, and discursive matter in the notes. Because the main purpose of this series is to allow readers to quickly come to an understanding of a Lincoln topic, we chose to encourage authors to focus on their topics rather than on historiography. At the same time, we wanted them to include information about their sources, either through the traditional use of notes and bibliography or through a short essay on sources. Following standard practice, notes, bibliographies, and essays on sources would all be part of the word count.

Meanwhile, the Press’s management team had changed. Lain Adkins, who had been the Press’s director and initial champion of the series idea, retired in early 2010. The department managers, some new, served together as a type of communal director for a year and a half until Editorial, Design, and Production Manager Barb Martin was named interim director in August 2011. Press management needed to reconsider some of the earlier decisions that had been made before the 2008 recession. Instead of releasing both hardcover and paperback editions, the managers decided to print hardcovers only. Management chose to price the hardcovers at an affordable $19.95 and to use the same price for e-books.

Only three years after the original series idea, SIU Press published the first four CLL books in the Fall 2011 season, from August 2011 to January 2012. They were Lincoln and the Election of 1860 (2011) by Michael S. Green (a manuscript that has the honor of being the first one submitted), Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley (2011) by Gregory A. Borchard, Abraham and Mary Lincoln (2011) by Kenneth J. Winkle, and Lincoln and the Civil War (2011) by Michael Burlingame.

At the time the books were released, the Press’s marketing team asked Dick, Sara, and me for a joint written Q&A. In response to the question of how we chose the topics, Dick responded, “We have tried, first of all, to cover the most significant topics associated with Abraham Lincoln—such as politics, race, religion, family, and civil rights. But we also wanted scholars and general readers to discover topics about Lincoln that merited more attention, for example, Lincoln’s political connections, his friendships and competitors, and ideas about him not yet studied in depth.” Sara pointed out that “Even though Lincoln’s life has been explored in thousands of books and other publications, we planned to present material which would make readers say either: (1) I didn’t know that or (2) I never thought of it in that way.”

Book reviews take time to come out. The first one, by James A. Cox in the Midwest Book Review, stated, “Each of these informed and informative titles is a welcome and highly recommended addition to personal, community, and academic library Lincoln Studies and 19th Century American History collections.” Other reviews followed, and most were positive. We were pleased by Joseph A. Truglio’s characterization of the books in Civil War News: “They are well edited, have none of the usual typos, and waste no space with ‘filler’ dialogue.” We particularly appreciated Reed Smith’s review in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association in regard to Borchard’s book: “The writing style is such that it can be appreciated not only by scholars but by amateur historians and even by high school students.”

In addition to positive reviews, we were pleased to see the books make their way into college classrooms as supplemental reading for students, particularly John David Smith’s Lincoln and the U.S. Colored Troops (2013). We sought to encourage this as a way to impart knowledge to young readers and to interest them, we hoped, in learning more about Lincoln and the Civil War era. For a time our series slogan was “Right size, right price, right for course adoption.”

Some books saw attention in major journals. In a review of John F. Marszalek’s Lincoln and the Military (2014), John C. Waugh’s Lincoln and the War’s End (2014), Edward Steers Jr.’s Lincoln’s Assassination (2014), and John C. Rodrigue’s Lincoln and Reconstruction that appeared in the November 2015 issue of The Journal of Southern History, Gerald J. Prokopowicz wrote, “Consecutively reading four volumes from the Concise Lincoln Library is the intellectual equivalent of consuming a handful of bridge mix. . . . The volumes are all approximately the same length and clad in dust jackets of the same design, but they are all very different inside.” He ended the review with this heartening sentence: “These books are uniformly well produced, well edited, written by experts on the relevant topic, and (above all) very short, as soon as readers finish one volume, they will want to start the next, if only to see what new approach lies within identical covers.”

As a nonprofit, SIU Press aims to reach the broadest possible audience. We seek to price our books reasonably so they are affordable. But we were unable to sustain the original low price for the hardcovers in the series. Supply costs went up, as they will. Further, we weathered a variety of financial storms. The economic downturn after the 2008 recession caused great turmoil in Illinois as the state and its universities struggled with a lack of funding and with budget cuts, both of which greatly affected a small university press already on a shoestring budget.

The Boren Fund money that allowed us to attract authors could not be used for marketing, production, or operating expenses. We were grateful that in 2012 the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation awarded us a grant to support traditional print advertising in trade magazines for the Press’s books about Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War. Perhaps getting the word out to Civil War enthusiasts would increase sales.

By 2015, however, only three of the nineteen CLL books in print at the time had sold well enough to cover the cost of their publication. This situation is certainly not uncommon among university press titles. In fact, because a majority of books published by academic presses do not make a profit, many are underwritten by subventions from institutions or individuals.

As the Press saw its institutional funding dry up, we worried about how we could complete the books we had agreed to publish in the CLL. Our tight budget and vanishing stipend meant that we could no longer afford to keep paying both Dick and Sara to continue editing the series. Sara kindly agreed to step down, which was a sorrowful necessity. So in 2015 we sought, and were granted, enough financial support from the wonderful Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation to allow us to continue publishing books in the series. Their gracious grant is acknowledged on all the books that it supported.

The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation’s lifeline kept the CLL afloat. From 2011 to 2021, we published the twenty-eight volumes in the Concise Lincoln Library—a remarkable achievement. Appropriately, we completed the series with a Fall 2022 release of a CLL paperback edition of the book that inspired the series: Jason Emerson’s Lincoln the Inventor.

After books are published, SIU Press managers keep a close eye on inventory. Once the cloth editions started selling out and excess stock was remaindered, we decided to release paperback editions using new technologies that have enabled us to keep high-quality books in stock and available without expensive warehousing fees. We are working toward making paperback editions of all the CLL books available. In addition, now that high-quality print-on-demand is available for hardcovers, we are working toward making hardcover editions of all the CLL books available again. This wonderful, unanticipated opportunity will allow us to make all the CLL books available in both hardcover and paperback for future generations. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that, as a member of the Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana, you can use the code FLC25 at www.siupress.com to receive a 25% discount on books in the Concise Lincoln Library.

All of the authors in this series have done exceptional work. Writing a short book is not an easy task, for it requires in-depth research and deep consideration about what to exclude as well as what to cover. Touching on the edge of other well-developed fields of study—such as law (Brian R. Dirck’s Lincoln and the Constitution [2012], Christian G. Samito’s Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment [2015], and Mark E. Steiner’s Lincoln and Citizenship [2021]); the environment (James Tackach’s Lincoln and the Natural Environment [2018]); and Indigenous history (Michael S. Green’s Lincoln and Native Americans [2021])—means authors have to understand the intricacies of both and to handle them well enough to satisfy experts in both fields. Many of the manuscripts came in higher than the 50,000-word count allowed, some much longer, and cutting one’s writing is never easy. It takes talent and hard work to be concise.

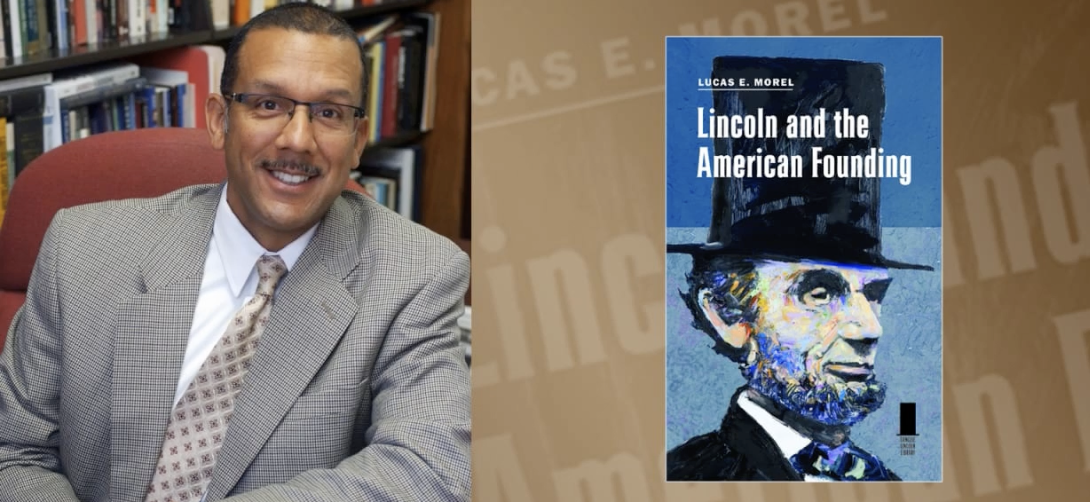

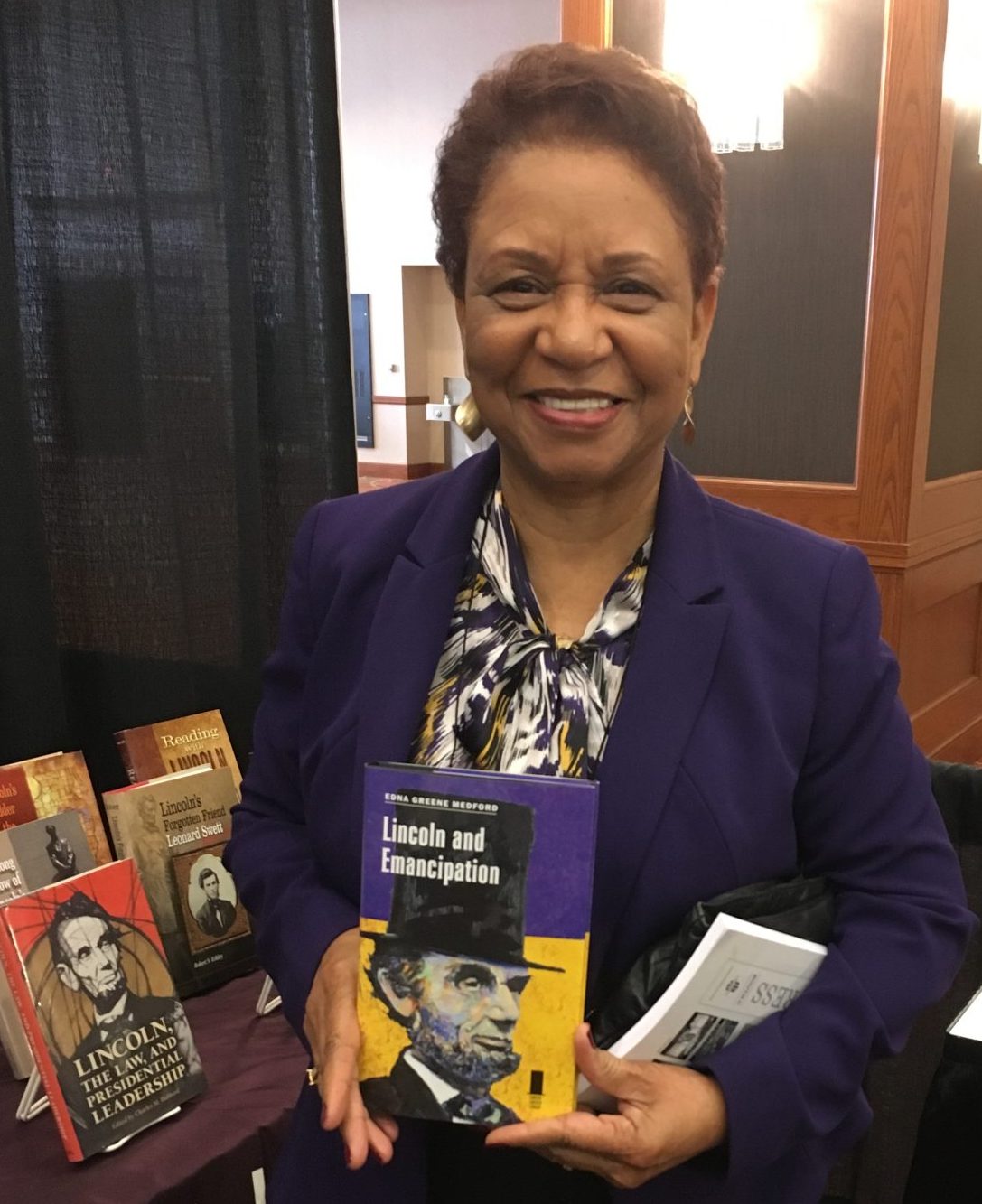

Although Ferenc “Frank” Morton Szasz died before he could complete his manuscript, his wife, historian Margaret Connell Szasz, stepped in, and both Dick and Sara contributed essays to round out Lincoln and Religion (2014). Three authors—Michael S. Green, Brian R. Dirck, and William C. Harris—each contributed two books. When Dick Etulain and I attended a Lincoln Forum talk by Richard Carwardine, we immediately knew we had to get him to write Lincoln’s Sense of Humor (2017) for us. Some of the books, like Jason H. Silverman’s Lincoln and the Immigrant (2015), may have inspired other historians to write longer works on the topic. Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein’s Lincoln and Medicine (2012) includes a not-to-be-missed description of the gunshot wound that killed Lincoln. Edna Greene Medford’s Lincoln and Emancipation (2015) puts enslaved Black people at the center of the story for their own freedom. Lucas E. Morel’s Lincoln and the American Founding (2020) hit a chord with the public when it came out during the COVID-19 pandemic. William C. Harris’s Lincoln and Congress (2017) should be required reading for today’s congressional leaders.

Many of the books align with our broad overview category, such as Michael Burlingame’s Lincoln and the Civil War and Richard Striner’s Lincoln and Race (2012). Others fit the idea of unexplored or underexplored topics, including Brian R. Dirck’s Lincoln in Indiana (2017), Thomas A. Horrocks’s Lincoln’s Campaign Biographies (2014), and Frank J. Williams’s Lincoln as Hero (2012).

Some of the originally targeted topics never came to fruition. Although we never published the elusive politics volume, we came at the topic in other ways—Lincoln and Congress by William C. Harris, Lincoln and the Election of 1860 by Michael S. Green, Lincoln and the Union Governors (2013) by William C. Harris, Lincoln and the Abolitionists (2018) by Stanley Harrold, and Lincoln in the Illinois Legislature (2019) by Ron J. Keller. We did not publish a book on Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, but we published other books about Abraham Lincoln’s relationships: Abraham and Mary Lincoln by Kenneth J. Winkle and Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley by Gregory A. Borchard.

Knowing that the series will endure and continue to enlighten readers about Abraham Lincoln is a gratifying result for all of us who have worked on the Concise Lincoln Library. As Daniel R. Weinberg, proprietor of the Abraham Lincoln Book Shop in Chicago, said during the presentation of the Wendy Allen Award, “These pithy insights into important topics of Lincoln’s life and times, each written by a noted Lincoln scholar, have allowed the general public—young as well as old—to access and understand perhaps the most important era in America’s past. Scholarly, yet approachable, the entire set is essential to any shelf devoted to those years. It will especially have a lasting effect for quickly introducing future generations to our shared past with basic knowledge in a lively and readable form.”

Sylvia Frank Rodrigue, co-author of Images of America: Baton Rouge (2008) and Historic Baton Rouge (2006), has worked in book publishing for more than thirty years. She acquires books for Southern Illinois University Press and runs Sylverlining, an editorial consultation service.