LINCOLN AND HIS GENERALS: Leadership during the Greatest American Crisis

LINCOLN AND HIS GENERALS: Leadership during the Greatest American Crisis

by Gary W. Gallagher

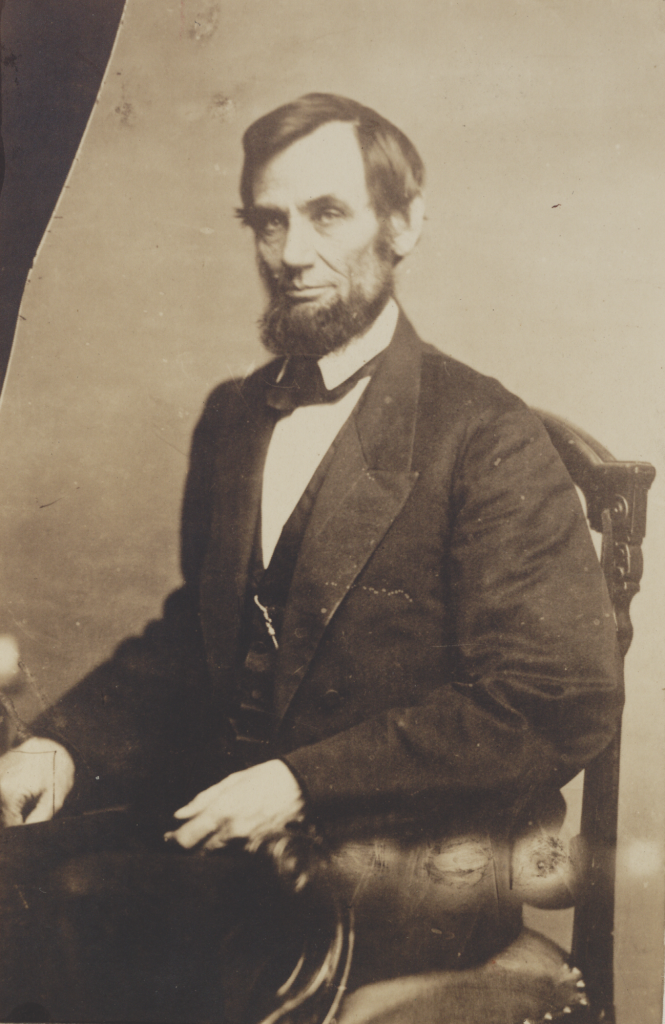

Abraham Lincoln faced greater challenges than any other president in United States history. Managing an immensely complex war effort in a democratic republic posed special challenges. He understood that victory depended on maintaining morale among both Democrats, who composed about 45 percent of the electorate and of Union soldiers, and Republicans. If events on the battlefield or political controversies on the home front—and the two often were inextricably linked—convinced enough loyal citizens that the war had cost too much human and material treasure, the Confederacy could win despite having far fewer soldiers and resources. Under the Constitution, civilian power was supreme, with military leaders always subordinate to Lincoln as commander in chief. Some generals understood this, some did not, and friction in this regard led to difficult times for the president. In the end, Lincoln found the right officers to command the nation’s armies.

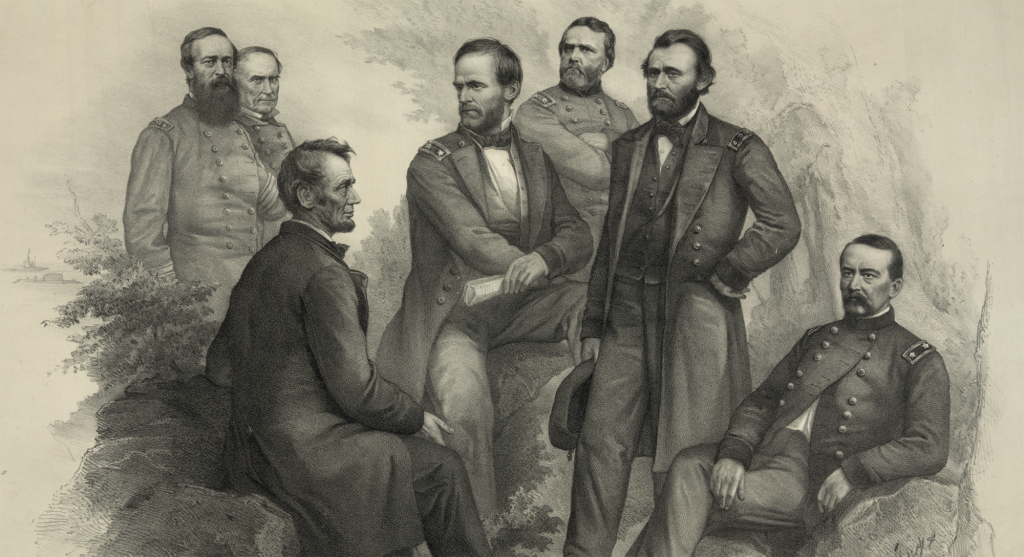

Lincoln possessed substantial constitutional authority in two key areas. First, he helped shape a national strategic policy designed to suppress the rebellion, reestablish the Union, and, after January 1, 1863, make emancipation a non-negotiable element to any resolution of the war. Second, he decided which generals would serve at the highest level of command. His decisions in naming generals, and the way in which he worked with those chosen, proved decisive in winning a war that as late as the summer of 1864 seemed likely to end in Confederate independence. Lincoln’s selection of Ulysses S. Grant to be general-in-chief in March 1864, and the two men’s resulting relationship, provided the foundation for eventual victory.

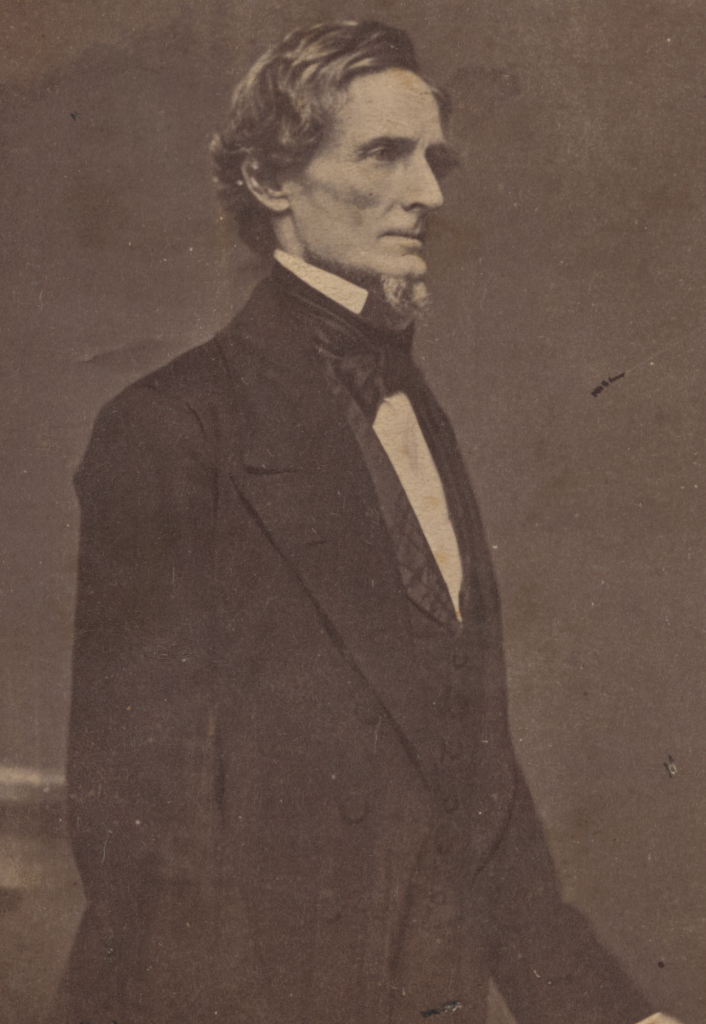

Lincoln brought little military or administrative experience to his new job. He provides a cautionary example for those who fetishize credentialing. Anyone examining the resumés of Lincoln and Jefferson Davis in 1860–1861 would conclude, without question, that Davis held far more promise as a commander in chief. He graduated from the United States Military Academy and successfully led a regiment of Mississippi Volunteer Infantry during the War with Mexico. Somewhat remarkably, Davis had commanded more troops in combat than anyone who became a general officer during the Civil War except Winfield Scott. He also had been a very innovative secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce and chaired the Senate’s Military Affairs Committee.

In contrast to Davis, Lincoln had no formal military education, had logged only a few weeks of militia duty during the Black Hawk War of the 1830s, and could boast of no administrative experience beyond running a very small law office. Although somewhat embarrassed by his humble origins and lack of formal education, Lincoln never sought to obscure his roots in Kentucky (his birthplace), southern Indiana, and Illinois. He spoke with an accent that clearly marked him as a western, rural outsider among college-educated easterners and had a predilection for homespun, often earthy, stories that invited dismissive comments from people, including many military officers, of more privileged backgrounds.

As a leader, Lincoln proved willing to put aside his ego, overlook slights, and tolerate prima donnas if they delivered results. He maintained an unwavering focus on the overriding national goal of crushing the Confederate rebellion and restoring the Union. He sometimes pursued unpopular policies to achieve that goal, knowing his actions would alienate various parts of the national electorate. Members of his own party tried to dump him from the Republican ticket in 1864, and some of his top generals openly opposed him, including George B. McClellan, who ran as the Democratic candidate seeking to deny Lincoln a second term.

Lincoln’s handling of military affairs revealed a tremendous capacity for growth and a willingness to learn from more knowledgeable subordinates. Early in the war, like most Americans, he believed one big battle would settle the issue. He pressed his generals to force a showdown in northern Virginia, questioning the argument that volunteer soldiers were green and needed more training. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott counseled against precipitate action but eventually supported a campaign against Confederates located near Manassas Junction. After a humiliating Union defeat at First Bull Run in late July 1861, Scott briefly lost his composure in front of the president and members of the cabinet: “I have fought this battle, sir, against my judgment. . . . I deserve removal because I did not stand up, when my army was not in a condition for fighting, and resist it to the last.” Lincoln acknowledged that he had been wrong and General Scott correct. Only training and experience, both of which took time, would convert the volunteers into soldiers. The war would take much longer, and require far more men and matériel, than Lincoln initially had imagined.

Lincoln also manifested a willingness to give great latitude to generals who might deliver results, even if they exhibited problematical traits or proved personally antagonistic to him. Here he kept his eye on the ultimate goal of victory and a restored Union. Carping, snubs, and posturing, all of which he endured in full measure in dealing with various generals, never persuaded Lincoln to think first about himself or to engage in efforts to punish the offenders.

As he matured as commander in chief, Lincoln settled on four requisites for military victory. First, efficient logistics would undergird successful military campaigning. He devoted considerable attention to the unglamorous tasks necessary to clothe, feed, and arm huge numbers of soldiers. Second, control of the Mississippi River, as well as other major waterways, would support Union initiatives and undercut Confederate efforts to thwart them. Winfield Scott’s influence was apparent regarding the centrality of the Mississippi. Third, U.S. commanders should target Confederate armies rather than cities. If the major Rebel forces were defeated, concluded Lincoln, the places they defended would fall into Union hands. Finally, and perhaps most important, the United States must apply its far greater industrial power and its 2 1/2 to 1 edge in manpower in the most sustained, relentless manner to win the war before civilian morale sagged. It should do so even at the risk of high casualties that might prove problematical in the near term but would shorten the war and save lives in the long term.

Lincoln’s relationship with top generals centered on his search for leaders who would utilize the nation’s superior manpower and resources effectively. His greatest disappointments arose when commanders failed to do so. An examination, in chronological turn, of Lincoln’s relationships with four officers in whom he placed trust to achieve the nation’s military goals reveal crucial elements of his leadership.

Lincoln’s dealings with Winfield Scott, the army’s senior officer, showcased his efforts to educate himself about military affairs. Nearly seventy-five years old at the time of Fort Sumter, Scott first gained combat experience in the War of 1812. During the War with Mexico in the 1840s, his strategic and operational planning and execution proved daring and innovative. Such was Scott’s skill in Mexico that the Duke of Wellington pronounced him “the greatest soldier of the age.” Although little known to most modern Americans, Scott surely ranks among the five best generals in U.S. history.

After an initial failure to follow Scott’s advice, Lincoln wisely sought to learn as much as possible from his venerable general-in-chief. Scott drew on vast experience and a first-rate intellect to propose a strategy the press labeled the “Anaconda Plan” because it sought to squeeze the life out of the Confederacy. Contemplating the problem of how best to crush the rebellion in the spring of 1861, Scott envisioned a naval blockade to deny war-related imports to the Confederacy and a combined army-navy strike down the Mississippi River to split the Rebel republic into two pieces. Should the Confederates continue to resist after the loss of key ports and control of the Mississippi, the United States, in Scott’s words, might have to “[c]onquer the seceding States by invading armies.” These proposed operations would take several months to organize and, cautioned the aging general, might stretch over two or three years and require hundreds of thousands of recruits to execute.

Well aware of political and popular pressures on Lincoln to strike an immediate blow to end the rebellion, Scott eventually proved successful in convincing the president that precipitate action held scant promise. Lincoln quickly accepted that it took time to train raw troops and collect supplies, basic military realities lost on many newspaper editors and members of Congress. Well before he retired on November 1, 1861, Scott had sketched a strategic blueprint that Lincoln embraced and which, in broad outline, anticipated how the United States waged the war.

George B. McClellan, who succeeded Scott as general-in-chief, provides an example of how much aggravation Lincoln would tolerate from a subordinate he believed might achieve military success. McClellan often behaved as someone who did not respect civilian superiority under the Constitution and who pursued his own plans to prosecute the war even when they deviated from those of Lincoln and other political leaders. Perhaps most tellingly, “Little Mac” never embraced the transition during the summer of 1862 to a harder kind of war that targeted the institution of slavery and war-related civilian property as necessary to defeat the Confederacy. He always hoped to restore the Union as it had been before the secession crisis of 1860–1861.

McClellan was just thirty-four years old in 1861 and had lived a life marked by one success after another. He graduated second in the class of 1846 at West Point and served as a member of Winfield Scott’s staff in Mexico. He resigned his commission in the mid-1850s to pursue a lucrative career as a railroad executive. During the Civil War, he demonstrated superb organizational but deeply flawed operational leadership. Undoubtedly charismatic and intensely self-referential, he forged an unmatched bond with his soldiers and never masked his opposition to many of the Lincoln administration’s policies.

In the wake of Union disaster at First Bull Run, McClellan converted a dispirited rabble of 35,000 men into a confident and well-trained force of more than 100,000 that he christened the Army of the Potomac. He also instilled in the army’s subordinate officer corps a culture of caution that lingered long past his own departure from command. Within that culture, he counselled avoidance of risk; obsessed about logistics and sought never to undertake a movement until everything was perfect; avoided delivering a knock-out blow to the enemy, aiming instead to defeat the Rebels just enough to persuade them to come back into the Union; and always manifested an awareness of possible political repercussions from his military decisions. In the end, McClellan created a powerful military instrument but proved unwilling to risk it in battle. He lacked what mid-nineteenth-century Americans would term the moral courage to take chances in pursuit of decisive results.

Lincoln entrusted McClellan with two jobs from November 1861 through early March 1862. As general-in-chief of all U.S. armies, he orchestrated overall strategic plans; as head of the Army of the Potomac, he led the republic’s largest and most important field command in the conflict’s most scrutinized theater of operations. John Hay, one of Lincoln’s secretaries, recorded how Lincoln warned McClellan that the dual positions of general-in-chief and head of the Army of the Potomac would be taxing: “In addition to your present command, the supreme command of the Army will entail a vast labor upon you.” “I can do it all,” replied the self-assured McClellan.

Lincoln wanted two things from McClellan: to keep his civilian superiors informed about the army’s plans and to carry out an aggressive campaign against the Confederates in Virginia. As time passed in late 1861 and early 1862, Lincoln realized that McClellan held back crucial information. Even more vexing, months elapsed without a major Union offensive while McClellan demanded more men and supplies and grotesquely inflated Confederate numbers to justify his inaction.

The youthful general betrayed contempt for both his military and political superiors in the summer and early autumn of 1861. “I am leaving nothing undone to increase our force,” McClellan wrote to his wife at one point, “but the old general [Scott] always comes in the way.” Scott finally grew weary of McClellan’s behavior and on November 1 retired as general-in-chief. As for Lincoln, McClellan described the president as “nothing more than a well-meaning baboon.” McClellan’s contempt for Lincoln reached a low point on November 13, 1861, when the president, his private secretary John Hay, and Secretary of State William H. Seward paid a visit to the general’s home. Absent when the three men arrived, McClellan later appeared but went upstairs without speaking to Lincoln. After twenty minutes or so elapsed, he instructed his butler to tell Lincoln—his commander in chief—that he had retired for the evening but would be happy to speak with the president at some other time. Upon leaving McClellan’s home, Hay castigated “this unparalleled insolence of epaulettes.” Lincoln, however, “seemed not to have noticed it specially, saying it was better at this time not to be making points of etiquette & personal dignity.”

McClellan often paraded his anti-administration politics. Failing to capture Richmond during the Seven Days campaign in June–July 1862, he nonetheless lectured Lincoln about policies supporting a hard war and emancipation. He insisted that “Neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of states or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.” In a letter written two weeks after his withdrawal from the battlefield at Malvern Hill, he sputtered, “I have lost all regard & respect for the majority of the Administration, & doubt the propriety of my brave men’s blood being spilled to further the designs of such a set of heartless villains.”

Lincoln never could get McClellan to act aggressively. In early March 1862, he removed his balky subordinate as general-in-chief but left him in charge of the Army of the Potomac. When McClellan unnecessarily retreated from Richmond in July 1862 and then, two months later, allowed Robert E. Lee to escape from Maryland unmolested after the battle of Antietam, Lincoln lost his patience. A note to McClellan dated October 25, 1862, conveyed his utter frustration with the general’s lethargic actions and unpersuasive excuses. Lee’s army had recrossed the Potomac River in one night after the battle of Antietam, but McClellan remained immobile near the battlefield more than five weeks later. He claimed he could not pursue Lee because the Union army’s horses “are broken down from fatigue and want of flesh.” “Will you pardon me for asking,” responded Lincoln with a mixture of sarcasm and anger, “what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?”

If McClellan had won victories and pressed Lee, Lincoln probably would have put up with his insubordination, open political opposition, and personal snobbery. But the president would not do so with a man who did not win. The day after the autumn elections in 1862, he sacked McClellan, timing the action to avoid a Democratic backlash at the polls. McClellan never led another army in the field but returned to the national spotlight in 1864 as the Democratic Party’s presidential standard-bearer.

A brief consideration of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker further illustrates Lincoln’s patience, and frustration, with problematical officers. Nicknamed “Fighting Joe,” the Massachusetts-born officer stood out as an aggressive presence in an army blessed with too little of that commodity. Hooker had worked tirelessly to supplant Ambrose E. Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac following the Union fiasco at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and the equally ignominious “Mud March” of mid-January 1863. A shameless self-promoter, he told Republicans in Congress what they wanted to hear, touted his own accomplishments, criticized Burnside, and emerged in late January as the president’s choice to lead the Army of the Potomac.

Lincoln initially looked the other way about Hooker’s troubling behaviors. The general talked publicly about how the nation needed a dictator to win the war, implying that he would make a good one. The president reacted in a remarkably perceptive and blunt letter. “I believe you to be a brave and skillful soldier,” began Lincoln. “You have confidence in yourself, which is a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm.” But, Lincoln added, “Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.” Hooker also bragged about what he was going to do to Lee, observing that he hoped God would have mercy on the Rebel chieftain because he, Joe Hooker, would not. Lincoln correctly feared that such bluster masked insecurity, offering one of his barnyard examples to make the point: “The hen is the wisest of all the animal creation because she never cackles until the egg is laid.”

Just before the battle of Chancellorsville, which took place on May 1–4, 1863, Lincoln reminded Hooker that “our prime object is the enemies’ army in front of us, and is not with, or about, Richmond.” To attain this objective, Lincoln urged his general to utilize his superior manpower—130,000 as against Lee’s 64,000. (Hooker, it must be noted, knew the relative numbers because he possessed excellent intelligence about the strength of Lee’s army.)

An abject failure of will and nerve at Chancellorsville brought humiliating defeat for Hooker. Despite Lincoln’s strong admonition, Hooker did not employ all of his strength. Indeed, two of the army’s seven infantry corps suffered very light casualties at Chancellorsville. Thousands of Union soldiers did not fire a shot. Lincoln spent several critical days at the telegraph office monitoring the action as it unfolded along the Rappahannock River in Virginia. A witness recounted how the president, upon realizing that Hooker had retreated, turned ashen and exclaimed, “My God! My God! What will the country say?” In June, when Lee marched north toward Pennsylvania, Hooker proposed to take the Army of the Potomac southward to capture Richmond instead of confronting the invading Rebel army. Lincoln had had enough, and after a dispute regarding the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry he fired Hooker. He simply would not countenance a general who seemed unable or unwilling to deliver a decisive blow against the Army of Northern Virginia.

Ulysses S. Grant, who apart from Lincoln did more than anyone else to defeat the Confederacy, forged a singular relationship with his commander in chief. He and Lincoln provide an example of how the nation’s constitutional system ideally functions during a military crisis. A determined president and a talented soldier who understood and accepted civilian oversight worked effectively toward a common national goal.

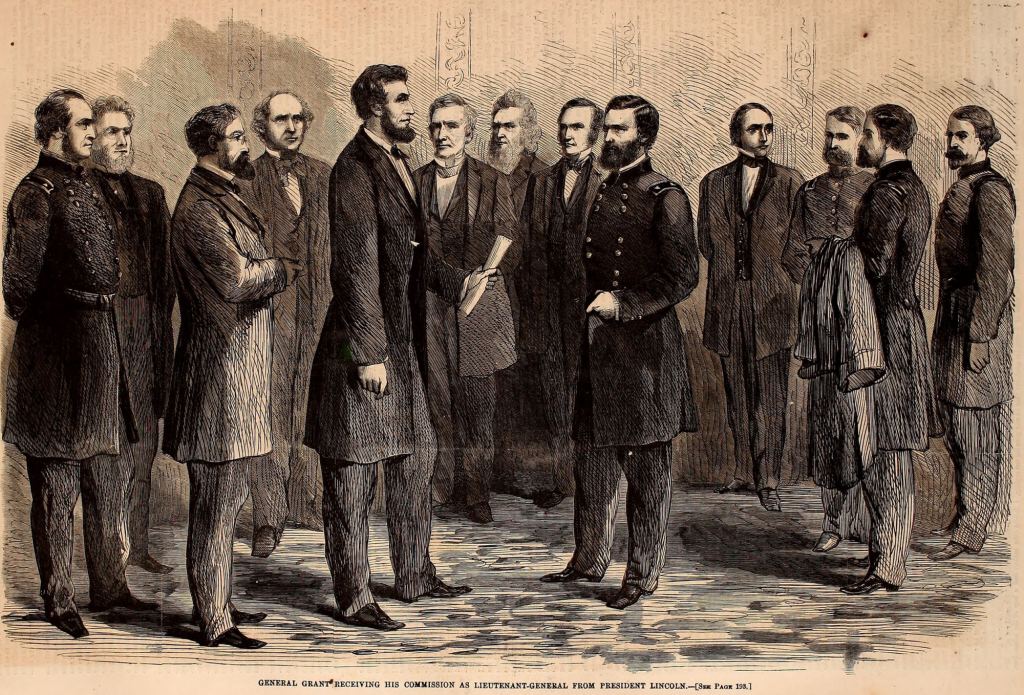

Thirty-nine years old when war erupted, Grant had logged both staff and line duty during the 1840s. He left the army in the 1850s, desperate to rejoin his family after difficult postings to the West Coast. Financial failure dogged him and his family for much of the 1850s—a period of adversity that toughened him. He came to prominence in the war’s Western Theater, which encompassed a vast expanse defined by the Appalachian Mountains on the east and the Mississippi River on the west. Victories in 1862–1863 at Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg (which opened the Mississippi River to full Union control), and Chattanooga (which severed a crucial rail link between Virginia and the southern and western Confederate states) brought Grant appointment as general-in-chief in early March 1864. He also received promotion to lieutenant general, a permanent rank previously held only by George Washington that Congress reinstated specifically for Grant.

In a short speech delivered to the general in front of members of the cabinet and a few others on March 9, 1864, Lincoln addressed Grant’s promotion to the rank previously held only by Washington. “The nation’s appreciation of what you have done, and its reliance upon you for what remains to do, in the existing great struggle,” remarked the president, “are now presented with this commission, constituting you Lieutenant General in the Army of the United States. . . . I scarcely need to add that with what I here speak for the nation goes my own hearty personal concurrence.”

Grant’s subsequent behavior validated the most important personnel decision of Lincoln’s presidency. In contrast to McClellan, Grant dutifully carried out all administration policies. Always aggressive, he rewarded subordinates who pushed their men to achieve decisive results. During his year with the Army of the Potomac in 1864–1865 (as general-in-chief he accompanied, but did not officially command, the army), he labored incessantly to root out McClellan’s culture of caution. In perhaps the most startling departure from McClellan, Grant made do with available resources rather than constantly asking for more, operating, in large measure, as a sort of anti-McClellan. In his Personal Memoirs, Grant offered a tribute to Zachary Taylor that might just as well have been written about himself: “General Taylor was not an officer to trouble the administration much with his demands, but was inclined to do the best he could with the means given him. . . . No soldier could face either danger or responsibility more calmly than he. These are qualities more rarely found than genius or physical courage.”

Grant possessed these “rare qualities” in abundance. Imperturbable, willing to take responsibility for his actions, and almost singular in his habit of making do with what the government gave him, he mirrored Lincoln’s determination, ability to focus on a goal, and, perhaps most important, refusal to be derailed by initial failure. Never making excuses for his setbacks or laying blame on subordinates or civilian superiors, he simply went back to the drawing board and tried something else. Examples of this attribute can be found at Vicksburg in the spring and summer of 1863, at Chattanooga in November 1863, and in the Overland Campaign against Lee in 1864.

No one saw the large strategic picture more clearly than Grant. As general-in-chief in the spring of 1864, he planned a series of offensives that would strike at both the Confederacy’s armies and at its capacity to produce and distribute the materials needed to sustain the war. His experience as a quartermaster during the Mexican-American War taught him the importance of logistics, and he targeted the economic, agricultural, and transportation underpinnings of the Confederacy through what scholars have labeled a “strategy of exhaustion.” Destroy the enemy’s ability to clothe, feed, and arm its soldiers, he believed, and the United States would not have to kill those soldiers in large and bloody battles.

Grant also understood the political pressures on Lincoln and adapted when necessary. At the time of his elevation to general-in-chief, he knew the northern public thirsted for a direct confrontation between him—the Union’s best soldier—and Robert E. Lee. He knew as well that Lincoln had wanted someone in charge in Virginia who would smash the Rebels. He thus incorporated a direct challenge to Lee and his army into his broader strategy of exhaustion. During the resulting Overland Campaign of May–June 1864, he applied ceaseless pressure that brought combat on a scale unknown even in this bloody war. Constant attrition between the first week of May and the middle of June produced more than 65,000 Union casualties in an army that began the campaign with 120,000 men. (To appreciate this scale of loss, imagine how Americans today would respond to news that U.S. military forces had suffered close to a million casualties in a six-week operation.) Later in the war, Grant embraced Lincoln’s vision for an easy peace when he offered generous terms to the Confederates who surrendered at Appomattox. Grant likely agreed with Lincoln’s views in this respect, but the point is that he did what his civilian superior wanted him to do.

In short, this was a model civil-military partnership. Lincoln gave Grant wide latitude, and Grant calmed Lincoln down on occasion, as when he reassured him that the capital was safe in the face of Jubal A. Early’s incursion in July 1864. Just before Vicksburg fell to Union forces in July 1863, Lincoln stated: “Grant is my man, and I am his for the rest of the war.” That was the case, and the leadership of these two men, more than any other factor, enabled the United States to emerge triumphant from the crucible of a mammoth war.

Anyone who visits the National Mall in Washington should take a moment at each end of that long, green swath. In front of the Capitol sits the imposing equestrian statue of Grant, dedicated in 1922 and bearing a single word: “Grant.” At the other end of the Mall, the Lincoln Memorial, also dedicated in 1922, faces eastward toward the Capitol from near the Potomac River. It is entirely appropriate that Lincoln and Grant face each other in the capital of the nation their superior leadership did so much to save.

Gary W. Gallagher is the John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War, Emeritus, at the University of Virginia. One of the most influential scholars of the American Civil War, and one of most engaging Civil War battlefield guides, he is the author or editor of more than fifty books, and the recipient of The Lincoln Forum’s 2021 Richard Nelson Current Award.