Herndon’s Informants: An Interview with Douglas Wilson

Herndon’s Informants: An Interview with Douglas Wilson by Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: This had to have been an enormous project. What first led you to undertake the task?

Douglas Wilson: I had been working on Thomas Jefferson for several years, mostly having to do with his early reading and education, the formation of his library, and his early influences. Most of this research was in support of an edition I had been asked to prepare of Jefferson Literary Commonplace Book for The Papers of Thomas Jefferson being brought out at Princeton. I had published a number of articles dealing with these matters in scholarly journals, and when the edition was completed, I decided that I wanted to write something for a general audience that focused on the importance of books and reading in Jefferson’s formative years. I had discovered in my teaching the advantages of presenting things in pairs — two short stories at a time, for example — which tends to bring out interesting differences and similarities. In looking for someone who shared Jefferson’s extraordinary attraction to books and reading in his formative years, I found a prime example in Abraham Lincoln.

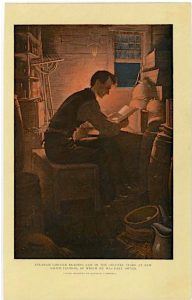

The differences in their circumstances were great, but their tenacious devotion to reading and learning in their early years was nearly identical. As a child, Jefferson began by reading his way through his father’s modest library of perhaps 60 books. Lincoln did something of the same sort with all the books he could lay hands on in his primitive frontier neighborhood. While my studies had taught me a great deal about Jefferson’s experience in this respect, I knew about Lincoln’s interest mostly by his reputation, so I set out to find the sources I would need to make the comparison. I had uncovered a lot of fresh information about Jefferson through extensive work in the various libraries where his early papers are found, but I very soon discovered that what is preserved about Lincoln’s formative years is heavily concentrated in a single massive collection of letters and interviews collected soon after Lincoln’s death by his law partner William H. Herndon.

But I was surprised to discover that this collection, which far exceeds anything available for any other nineteenth-century president, had never been published in a scholarly edition and consequently was generally known for only a limited number of key items dug out by the handful of scholars that had ventured into the collection. I don’t have time here to go into how and why this invaluable collection was not better known and consulted, except to say that it had not been publicly available for general use until it was acquired by the Library of Congress in 1941, and then accessible only by means of a very poor quality microfilm edition that was hurriedly created as a preservation measure and was very hard to use. Perhaps even more of a discouragement to its widespread use was the low regard in which Herndon had come to be held by the leading Lincoln scholars.

SG: How long did it take from concept to publication? What was the first thing that you had to do?

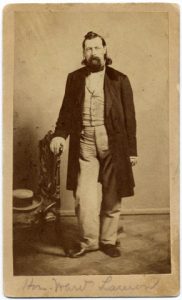

DW: Second question first. After I had read my way through the microfilm of these amazing materials, I persuaded my teaching and research partner at Knox College, Rodney O. Davis, to join me in a partnership to remedy the problem of access by producing a scholarly edition of all the letters, interviews, and statements about Lincoln that Herndon acquired in his searches. This turned out to be a much larger order than we anticipated for a number of reasons. First, while it was true that by far the largest collection of these documents was, indeed, in the Library of Congress, a nation-wide survey that we conducted early on disclosed that there were documents that fitted our definition in several other repositories. Another reason was that Herndon, having amassed a sizeable amount of testimony, took the precaution of having it transcribed. Those transcriptions are still extant at the Huntington Library, and they include original testimonies not in the Library of Congress collection. Many of the original accounts written by the informants are ungrammatical, ill spelled, and poorly punctuated. John G. Springer, the person Herndon hired to transcribe what Herndon called his “Lincoln Record,” regularized the grammar, punctuation, and spelling, and introduced errors of his own by mistaking one word for another. It was Springer’s transcriptions that Herndon sold to Ward Hill Lamon in 1869, and that Lamon’s ghost-writer, Chauncey F. Black, drew on in writing Lamon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln (1872). This book was extremely unpopular when it appeared, precisely for its use of anecdotes and testimony collected by Herndon that were generally considered unbecoming and inappropriate in recounting the life of a great national martyr, even if true.

The other part of your question, having to do how long the project took, is worth considering, because from the inception of the project to its publication in 1998 was a period of about nine years. We began by transcribing the documents available on the Library of Congress microfilm, while at the same time we were conducting our national survey of likely repositories. Most libraries that responded had only a small number of items that they were willing to duplicate and share with our project, but two libraries had such sizeable holdings that we needed to examine on site — The Illinois State Historical Library (since incorporated into the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum) in Springfield, Illinois, and the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The former was nearby and therefore readily accessible; working in the latter required considerably more in terms of time and financial support. In preparing the final manuscript for publication, we took the precaution of checking our manuscript against the original documents, most of which were at the Library of Congress, where the process required five weeks of double reading. In addition to that was the preparation of the explanatory matter that described the parameters of the material being presented, the editorial procedures employed, and the history of Herndon’s efforts to collect information about Lincoln’s early life. All of this required about seven years, but the extent of the testimony and the exacting editorial procedures necessary for preparing the manuscript for the press required an additional two years before the appearance of the finished work in 1998.

SG: Did Herndon keep systematic records?

DW: I think it is fair to say that Herndon knew the value of the testimony that was given to him, orally or in writing, and he took pains to preserve and protect it against loss. He had what proved to be the bulk of it transcribed in late 1866, and took the precaution of having these items bound in three large volumes, which he placed in a bank under lock and key. One can argue that he should have done this with the originals and kept the transcriptions for use in his home for consultation. He seems to have wanted to have the originals close at hand in the event that anyone challenged him with misrepresentation. When he went to give a speech, he would take some of his collected testimony with him in the event that he was challenged, and as a result, he admits that this sometime resulted in the loss of one of his “records.” We have no way of knowing how these records were organized in his study, but doubtless he had some kind of organizing principle. Personally, I wouldn’t be surprised if he relied very heavily on his memory, which seems to have been very good, with the usual caveat for age. Whether these procedures count as “systematic” or not, he was aware that he had in his possession priceless materials, and he acted to assure the preservation of these invaluable testimonies.

SG: How/when did he first begin to correspond with national figures?

DW: Herndon was a serious person even as a young man, and he thought nothing of sending off letters of inquiry to the some of the most notable of national figures —such as Ralph W. Emerson or William E. Garrison. Some of the responses he got from these early ventures suggest that his answers were perfunctory at best, but he did strike fire with certain national figures who responded candidly and substantially. This was to pay dividends when Lincoln became a national figure, as these forthcoming correspondents were in a position of getting information about this obscure Illinois politician directly from his law partner.

SG: I was interested in the fact that he corresponded with Theodore Parker. Who initiated this correspondence? Did he subscribe to Parker’s Transcendentalist philosophy?

DW: I am pretty sure that Parker did not initiate the correspondence with Herndon, as their exchanges go back to before Lincoln became nationally known. In the years before Lincoln gained a national reputation, we know that Herndon had been writing to Parker, as well as other Eastern figures, such as Wendell Phillips. I think we know enough about his early practice of writing to famous persons to say that Herndon was an eager intellectual intensely interested in ideas and keen to communicate with leading thinkers. One might also point to the situation that it was much more common in Herndon’s day to write to famous writers and ask for clarifications and other questions related to their published views. About Parker’s Transcendentalist philosophy, I would say that Herndon wrote not as a disciple or fellow transcendentalist, but as someone who was interested in what the leading lights were writing about.

SG: Please comment on the fact that there are several letters written during Lincoln’s 1858 campaign for the Senate.

DW: Herndon worked very hard on Lincoln’s campaign and in a number of different ways. First, he volunteered to speak at places that were missed by Lincoln’s own energetic speaking schedule, and he

seems to have done a fair amount speaking. This was important, because he had a reputation as a public orator in his own right, and thus could draw a crowd. Next, he was constantly looking for oratorical ammunition for his partner to exploit, such as reading the prominent Democratic newspapers’ coverage of the campaign. He was an omnivorous reader, and he put his appetite in this regard to find possible points of attack, possible points suggesting weakness or strength. And being an abolitionist, which Lincoln was not, he could keep Lincoln informed on how this valuable community could be beckoned or

appeased.

SG: Can you discern a difference in the dialogue between Herndon and his “informants” before and after Lincoln’s rise to national prominence?

DW: This is a good question to end on, because it is quite important to understand that he did not conduct any kind of survey of Lincoln’s former friends and associates until after Lincoln’s death. Lincoln as president was a much-criticized and often beleaguered chief magistrate, hated by the Peace Democrats (who were very strong in Illinois), and the object of constant criticism from the leaders of his own party. If Herndon had gone out in the area of New Salem and queried the old friends of Lincoln’s younger days, say in 1864, he would have gotten a very different response. But immediately upon being

assassinated, Lincoln became an instant martyr, the savior of his country. When Herndon made his first inquiries just weeks after Lincoln’s assassination, and in a largely Democratic, anti-war community, the feelings of these old friends were accordingly muted, and for the most part they only had good or at least neutral things to say. And here it is important to say that much of what they told Herndon depicts a young, lively, and quite likeable Abraham Lincoln, not the misguided president they believed him to be.

This is not to say Herndon got a false picture. Indeed, he rescued the memories of the early life of a man who would be, and still is, one of the best known and most admired leaders in Western history.

Douglas Wilson is the George A. Lawrence Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of English at Knox College.