An Interview with Louis P. Masur

An Interview with Louis P. Masur

An Interview with Louis P. Masur

by Jonathan White

Louis Masur is Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at Rutgers University. He is a cultural historian whose publications include books on Lincoln and the Civil War, capital punishment, the events of a single year, the first World Series, a transformative photograph, and a seminal rock ‘n’ roll album. His publications include The Sum of our Dreams: A Concise History of America (2020), Lincoln’s Last Speech: Wartime Reconstruction and the Crisis of Reunion (2015), Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union (2012), and The Civil War: A Concise History (2011). His latest book is A Journey North: Jefferson, Madison, & the Forging of a Friendship (2025). Masur’s essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, and Slate. He has been elected to membership of the American Antiquarian Society, the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and the Society of American Historians.

Jonathan White: Your first book, Rites of Execution (1989), explores the history of capital punishment in the United States from the American Revolution to the Civil War. What sort of changes in criminal justice occurred between 1776 and 1865? And what caused these reforms to occur?

Louis Masur: I became interested in the topic of the movement against capital punishment when I read several pieces by the abolitionists who included opposition to the death penalty in the panoply of the reforms of the day: antislavery, temperance, peace, education, prison reform. Following the Revolution, activists saw the death penalty as monarchical and antithetical to a republican form of government. Benjamin Rush was one of the early proponents of alternative punishments and the penitentiary emerged as a substitute for capital punishment. In addition to political reasons to oppose capital punishment, there were religious ones, and a drift away from Calvinism led liberal religious sects—Quakers, Unitarians, Universalists—to oppose the death penalty. As a result, in the period before the Civil War, the number of crimes for which one could be executed declined and some states abolished the death penalty.

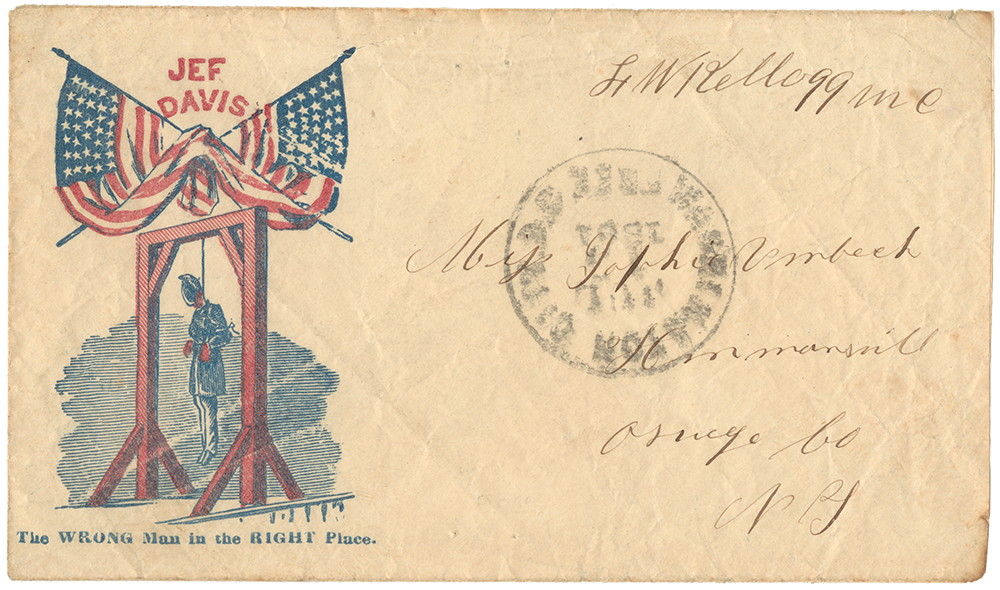

Rites of Execution also explores the shift from public to private executions that occurred in antebellum America, a shift that spoke to larger changes in the culture. Executions were moved inside prison walls, in part because the sight of hangings affronted emerging middle-class sensibilities. In many ways, the Civil War put an end to this first movement to abolish the death penalty as activists found it a challenge to generate sympathy for death when untold numbers were perishing.

JW: Rites of Execution came out of your dissertation, which you completed at Princeton. I understand that you were a research assistant for James M. McPherson when he was writing Ordeal by Fire. What was it like to work with him?

LM: My first graduate seminar was with Jim McPherson. I wrote a paper on William Lloyd Garrison and the doctrine of immediate emancipation. From there, I was hooked on that generation of reformers. I learned a critical lesson while serving as Jim’s research assistant: always go back to the primary sources. Ordeal by Fire was a vast synthetic work and Jim would have me check quotes that he found in various secondary works. Time and again, I would go to the sources and discover that the writer had gotten it wrong: a word here, a word there. Sometimes something more egregious that changed the meaning of the quote. It was a lesson that served me well when I wrote my concise history of the Civil War.

The Princeton history department was a remarkable place to be at that time, 1979–1984. It was dominated by Europeanists such as Natalie Davis, Lawrence Stone, Anthony Grafton, and Robert Darnton. (At some point, the department was featured in the New York Times.) What that meant was that Americanists could fly under the radar. Jim hadn’t yet won the Pulitzer Prize for Battle Cry of Freedom. Dan Rodgers arrived in 1980. John Murrin, Stan Katz, Nancy Weiss and others created a collaborative and supportive environment, though for someone like me, coming from a state university, Princeton posed various challenges. I was a lecturer at Princeton from 1985–1986 before taking my first tenure-track position. Amazing how quickly forty years can pass!

JW: On Lincoln’s birthday in 1831 the United States witnessed a solar eclipse—something you’ve written an entire book about. Tell us about that year. And why did this astronomical event captivate the nation in the way that it did?

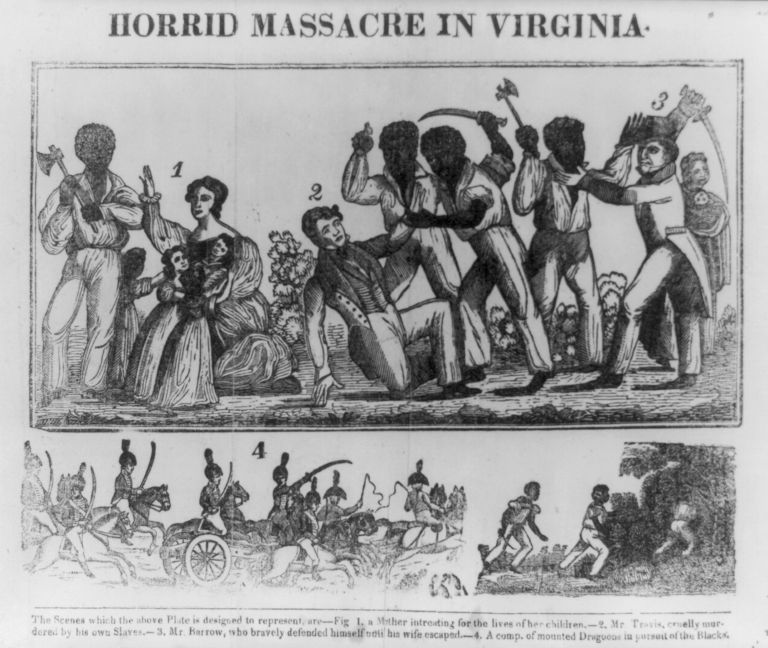

LM: My idea for the book emerged in that first graduate seminar I took. Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator began circulation on January 1, 1831, and I continued to note other seminal events centered on that year: Nat Turner, nullification, Andrew Jackson, evangelical awakenings, Indian removal. Tocqueville and Beaumont visited in 1831. I use the eclipse and the themes of darkness and light to write about one of the seminal years in American history. The book in many ways is about the staging ground for the Civil War that would erupt thirty years later. It was a challenging book to write in terms of figuring out the narrative structure. One day I woke up and wrote the line, “the heavens darkened and Nat Turner prepared to strike.” From there, after years of research and thinking about the events of the year and how to weave them together, the book came easily.

JW: Lincoln was a marginal figure in your first two books, but in recent years you’ve written several books that focus entirely on him and his times. What led you to make this transition?

LM: If there is something that ties together the approach I take in my work, it is the idea of the world in a grain of sand. I identify moments or texts (1831; a photograph; a record album) and seek to unpack them. Any nineteenth-century historian at one point or another seeks an opportunity to engage with Lincoln and that time came for me when I started to think about the period between the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and the final Proclamation—one hundred days. While much had been written about the Emancipation Proclamation, I could not find much that focused on this pivotal period. The proclamation changed in important ways between September 22 and January 1, and I sought to explicate how those changes came to be and how Lincoln navigated those stirring days.

JW: The Emancipation Proclamation is often criticized today. Some see it as little more than a political ploy, while others say it didn’t really accomplish anything. Many of Lincoln’s critics also say that he waited too long to release it. What do you say to critics of the proclamation to help them understand Lincoln’s approach to slavery during the Civil War?

LM: I have little patience with critics of the Emancipation Proclamation. Frederick Douglass understood it as one of the polestars of American liberty along with the Declaration of Independence. Why did Lincoln wait? Because he had to, because he did not have the power as president to abolish slavery, and it took time both to see how the war progressed and to develop the doctrine of military necessity. It took time for the enslaved to run away and help force Lincoln’s hand. It took time to prepare the public for the action he decided to take in the summer of 1862.

Critics say it did not free all the slaves. Of course not. Lincoln had no power over slavery in the four border states. Slavery was a state institution. And the proclamation is filled with exceptions. It had to be. The rationale for freeing the slaves was military necessity. You cannot therefore free those enslaved persons where there is no longer a military necessity (hence the exceptions). To do so would be to make a mockery of the legal grounds on which the president as commander in chief is acting. Lincoln was nothing if not logically consistent. Read his rebuke to Salmon Chase on September 2, 1863. Why critics of Lincoln do not understand his clear position is confounding.

As for it not accomplishing anything, tell that to the thousands of enslaved persons who found freedom by running away after the proclamation was issued, tell that to the thousands of Union soldiers who rejoiced to now be fighting not only for Union but also for freedom, tell that to the tens of thousands of Black soldiers, whose service was authorized by the Emancipation Proclamation, and who helped win the war and rights to citizenship. Did it free all the slaves? No. Were most of the enslaved freed only on paper? Yes, but paper counts. The Declaration of Independence was a paper decree. The Emancipation Proclamation sets the stage for the Thirteenth Amendment. It transforms the meaning of the war.

At some point in the twentieth century, the luster of the Emancipation Proclamation faded as some sought to diminish Lincoln’s role as great emancipator and instead place the emphasis on how the enslaved freed themselves. “Who freed the slaves,” some historians asked? Many factors explain emancipation, but there is no answer to the question without Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation.

JW: You call your book on this subject Lincoln’s Hundred Days (2012). Why is it important to focus on that particular stretch of time?

JW: You call your book on this subject Lincoln’s Hundred Days (2012). Why is it important to focus on that particular stretch of time?

LM: History is the study of change over time, and the hundred days between the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and the final decree illustrate this axiom as well as anything. One of my favorite assignments is to give students the two documents and ask them what changes? Remarkably, despite the opposition to the preliminary proclamation, the final document is more radical. Lincoln removes any reference to colonization and he authorizes the enlistment of Black soldiers. He suggests that the enslaved have a right to self-defense and he calls emancipation an act of justice. This despite punishing losses for the Republican Party in the November elections. Having made up his mind to free the slaves, Lincoln would not back down. He was often slow and deliberate in reaching a decision, but once he decided he seldom wavered. He would later say in his letter to James Conkling, “the promise, being made, must be kept.”

Lincoln suffered terribly during those hundred days. After Fredericksburg, he lamented “if there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.” And yet, at the same moment, he wrote his remarkable letter to Fanny McCullough in which he offered condolences on the death of her father and assured her she would be happy again. Considering that juxtaposition alone is enough to warrant a lifetime of studying Lincoln.

JW: You followed up with a book on Lincoln’s Last Speech (2015). I always get goosebumps when I think about what it must have been like that night at the White House. Please describe the scene for us.

LM: April 11 was a Tuesday and as dusk approached the White House was “brilliantly illuminated” and bonfires and celebratory rockets lit up the sky. It had been two days since Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. Bands played; people sang. Tad admired the parades and at one point waved a captured rebel flag. Crowds called on Lincoln to speak. He did so briefly the day before, at one point calling on a band to play “Dixie,” joking that the Union would appropriate it as a captured prize of war. He promised that he would speak to the crowd the next evening, the eleventh. Mary Lincoln invited guests who could be seen through a window adjoining the portico from where Lincoln would speak. Elizabeth Keckly described the “weird, spectral beauty of the scene.”

One of Mrs. Lincoln’s guests was Marquis Chambrun, a French attorney who arrived in February 1865 and quickly became a favorite. He said of Lincoln that “as President of a mighty nation, he remains just the same as he must have appeared while felling trees in Illinois.”

JW: What sort of vision for Reconstruction did Lincoln lay out in his final speech? And how was his speech received?

LM: I wrote an entire book on the speech, so it is hard to summarize. His vision was to double down on the process he had initiated with his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in December 1863. He stood by his plan of government by which states would be restored to the Union: when loyal governments were established and state constitutions that abolished slavery adopted. Much of the speech was devoted to urging the readmission of Louisiana on these terms. In typical Lincoln fashion, he used a metaphor to make his meaning plain to the people. Louisiana’s government might not be perfect, but the government was “only as it should be as the egg is to the fowl.” He asked whether “we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it.”

Perhaps the most remarkable element of the speech is that he publicly endorsed Black suffrage for those who were educated and had served in the Union military. As with so many topics, he evolved to this position. A year earlier he wrote the governor of Louisiana and suggested Black men be included in the elective franchise, but added the suggestion was to him alone and not for public consumption. Democracy was everything to Lincoln and he knew that only with the franchise could the freedmen have their interests represented. This is not to say there was not some political expediency to it: Black men would vote overwhelmingly Republican until the 1930s.

Reactions to the speech were predictably partisan. He was praised for his statesmanship and common sense. The New York Times, a pro-administration paper, thought the speech reserved and wise. Others, however, thought the speech “fell dead” and was “vague.” Some mocked the chicken/egg metaphor, suggesting that rotten eggs should be smashed. What was clear to all, a battle with Congress over reconstruction lurked ahead. But that day Lincoln was jubilant. Congress would not be in session until December; he would work it out before then. He was not given that chance. John Wilkes Booth attended the speech. He turned to Lewis Powell and declared “that is the last speech he will ever make.” Three days later, he acted.

Historians enjoy counterfactuals and “what if Lincoln had lived” is a useful one. It is too simple to believe that he would have solved the intractable problems of Democratic Party insurgency and racial hatred that came to characterize the era of Reconstruction. To be sure, the freedmen would have been better off with a president willing to use the federal government to help the transition from slavery to freedom. Frederick Douglass observed “whoever else have cause to mourn the loss of Abraham Lincoln, to the colored people of the country his death is an unspeakable calamity.” But counterfactuals take us only so far. In my concise history of the Civil War, I quote the novelist Cormac McCarthy: “We weep over the might have been, but there is no might have been. There never was.”

JW: Most of your work is on cultural history. How does your work on Lincoln fit into your broader scholarship? You’ve also written about rock ‘n’ roll, baseball, and civil rights in the 1970s. Tell us a little bit about your work in these areas.

LM: I define cultural history broadly and intellectual history and political culture certainly fit the category. But more than that my work is an ongoing meditation on the meaning of America. Part of that enterprise involves looking at different sources and unpacking them: not only written texts, but images and songs. What is more American than baseball (soldiers played during the Civil War) and I’ve written about the first World Series. I’ve written about a Pulitzer Prize- winning flag photograph, The Soiling of Old Glory, and offer a way to read the image that promotes visual literacy (in researching that book, I learned that Old Glory first came into prominence as a nickname for the flag during the Civil War). I’ve also written about Bruce Springsteen’s album Born to Run, a meditation on the “runaway American Dream.” Springsteen has said that he has “spent his life judging the distance between American reality and the American dream.” So too Lincoln.

JW: At Rutgers you teach a course on “The American Dream.” What do students encounter in your class? And how do they tend to respond?

LM: I love that course. It is filled mainly with first-year students for whom it may be their only humanities course. I assign all sorts of readings, including Lincoln, of course. They read Ben Franklin’s Autobiography, the first “how to” book, and Jhumpa Lahiri’s wonderful novel The Namesake. It’s fascinating to discuss with them the various meanings of the American dream. For most, it’s about rags to riches (Lincoln’s “prudent, penniless beginner”). Others understand it’s about a set of principles: democracy, equality, justice. We explore the mythology of the frontier and immigration. Of course, race is central to the course. Students watch and discuss Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. We spend a lot of time dissecting Langston Hughes’s poem “Let America Be America Again.”

The course is very popular, and I hope I get students to think harder about what it means to be an American. Some of them, to my delight, become American Studies and History majors and minors. I wrote a concise one-volume history of the United States that came out of teaching that course. It’s called The Sum of Our Dreams, and the title comes from a speech given by Barack Obama. The preface of the book is titled “Land of Hope and Dreams.” That’s a Springsteen song. It’s all connected!

The course is very popular, and I hope I get students to think harder about what it means to be an American. Some of them, to my delight, become American Studies and History majors and minors. I wrote a concise one-volume history of the United States that came out of teaching that course. It’s called The Sum of Our Dreams, and the title comes from a speech given by Barack Obama. The preface of the book is titled “Land of Hope and Dreams.” That’s a Springsteen song. It’s all connected!

JW: In your scholarship, you are especially interested in questions of narrative and literary nonfiction. You once wrote a piece titled “What Will it Take to Turn Historians into Writers?” Can you discuss that?

LM: I was a double major in History and English in college and I’ve always been interested in the boundaries between fact and fiction. Someone once said the only difference between historians and novelists is that historians find facts whereas novelists invent them. Ever since the profession was founded, there have been periodic laments about “dry-as-dust” history and calls for more vigorous narratives. But academically trained historians focus more on historiography and argument, bloating their works with theses and notes. The writing of lively books intended for a general audience seemed to have been left mainly to the journalists, and in some ways still is today. Allan Nevins and Bruce Catton were both journalists.

It is one thing to be a historian, but perhaps another to consider oneself a writer. In a letter to Walker Percy, Shelby Foote summarized the endeavor this way: “Most people think mistakenly that writers are people who have something to tell them. Nothing I think could be wronger. If I knew what I wanted to say I wouldn’t write at all. What for? Why do it, if you already know the answers? Writing is the search for the answers, and the answer is in the form, the method of telling, the exploration of self, which is our only clew to reality.”

I’ve never moved explicitly into fiction, as Simon Schama did in his brilliant Dead Certainties, which offered an extended meditation on historical truth. But fiction, if well executed, can be remarkably effective in communicating the truths of the past. For example, I regularly assign Michael Shaara’s Killer Angels in my Civil War course. Students love it and there is no doubt it brings the Battle of Gettysburg alive. Historians would do well to think about what we might learn from fiction in writing nonfiction that strives for literary merit—how we can make our narratives come alive with character, plot, dialogue, form, and language while hewing to the facts as we know them.

Writing is hard. Anne Dilliard once said, “it is no less difficult to write sentences in a recipe than write sentences in Moby-Dick, so you might as well write Moby-Dick.” None of us can. But the striving is worthwhile.

JW: What are you working on now?

LM: I’ve just finished a book titled A Journey North: Jefferson, Madison, & the Forging of a Friendship. The opening sentence is “Jefferson loved to travel; Madison not so much.” It’s no “Call me Ishmael,” but it suffices. The book narrates a month-long trip the two took in late spring 1791 through New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Vermont. Theirs is the most important friendship in American history, and the journey, a Founding Fathers road trip, deepened that friendship at a time of acute political division. The story allows us to see them as something other than politicians. I focus on their interests in botany, entomology, racial classification, and linguistics, which were paramount throughout the trip. It will be my tenth book. Not sure what is next, but I can feel Lincoln drawing me back.

JW: That sounds fascinating, but I certainly do hope that Lincoln draws you back. Thank you so much for joining us!