An Interview with Jon Grinspan

An Interview with Jon Grinspan

by Jonathan W. White

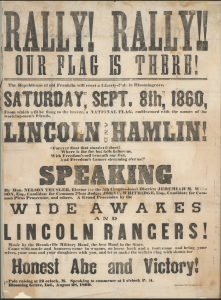

Jon Grinspan is Curator of Political History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. His work explores the history of American democracy, with a focus on ways the formative, forgotten 1800s shaped our political present. His three books and many New York Times articles have explored nineteenth-century youth politics, frustrations with democracy, and militant antislavery clubs, as well as off-beat subjects like Civil War coffee, Gilded Age saloon life, and the best tricks for stealing an election. At the Smithsonian, he focuses on collecting objects from past and contemporary political events to tell the story of America’s struggle for democracy to museumgoers in the future. His latest book, Wide Awake: The Forgotten Force That Elected Lincoln and Spurred the Civil War (2024), was a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize and won both The Lincoln Forum’s Harold Holzer Book Prize and the Society of American Historians’ Francis Parkman Prize.

Jonathan White: Tell us about your day job. What is it like to be Curator of Political History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History?

Jon Grinspan: The beauty of being a curator is that nobody really knows what we’re supposed to be doing. It takes so many forms. I have colleagues at the museum whose days are entirely different from mine. To me, the Smithsonian’s original mission (“the increase and diffusion of knowledge”) is a kind of thesis and a challenge: in what ways can we increase our knowledge of the past, and how can we diffuse it to the broadest public audience?

I usually target those who might not make it to the museum on the National Mall, and try to bring historical research to contemporary conversations through and books and articles. Those serve as tentpoles for talks, events, programs, and projects. And each can reach multiple populations, so one day we might meet with senators, and then it’s kindergartners the next day.

The museum and its collection serve as an anchor, as an endless source of research, and often as a kind of goad, posing new questions to explore. Giving tours to diverse audiences is vital, because people ask questions we just never think of. And I work to expand our collections. Although my scholarship focuses on the nineteenth century, much of our collecting is contemporary, drawn from recent political events like rallies, protests, campaigns, conventions, and now riots. Some of our best work comes from viewing a 150-year-old object next to one collected last week.

Last but not least, it’s a physical job to steward these collections. You have to be ready to climb on top of a tower of steel quarter units or (carefully) dust U.S. Grant’s inauguration carriage.

JW: What are some of your favorite artifacts?

JG: I particularly love a Wide Awake torch we recently collected in Milford, New Hampshire. Its owner marked the year “1860” for its first use, and then participated in torchlight presidential campaign rallies over the next half century, marking “1864,” “1868” all down the shaft, through “1904.” It’s like an artifact of democratic engagement over time. Then there is our incredible trove of Lincoln materials: his gold watch (found to contain secret inscriptions by D.C. jewelers), the coffee cup he drank out of the night of his assassination, even the hoods his assassins wore when on trial.

Other objects—like the Woolworth lunch counter where Civil Rights protesters famously held a sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960—are powerful because they combine basic, quotidian functions with powerful moments in our history. And some objects I like simply because I’m shocked they survived into the twenty-first century, like a Log Cabin (basically made out of Lincoln Logs) from the 1840 campaign.

Really, there are too many gems to name them all.

JW: Much of your scholarship has focused on young people in the nineteenth century. How did you get interested in that subject?

JG: Originally, I liked youth because it was universal, one of the rare experiences we’ve all shared across other divisions, and one that had been neglected in the study of politics. On top of that, the sources were just incredible. Nineteenth-century young people poured their hearts, and their many worries, into diaries and letters in a way older people and later generations rarely would. Finally, as I grew interested in exploring the long sweep of nineteenth-century politics, and the high turnouts they enjoyed, young voters emerged as the fuel that sustained that model over time. If you’re going to study a system that perpetuated itself across generations, among diverse populations, new immigrants, new states, etc., you have to consider who is feeding into this system.

And it was easy to make readers empathize with the struggles of a 16 year old, to see the humanity and the humor in their stories.

JW: As a slight tangent, what was it like to study the Civil War at the University of Virginia? There’s such an incredible community of faculty and students there, I imagine it must be an amazing place to work.

JG: Often, in my life, I’ve only afterwards realized how lucky I’ve been to end up in a certain environment. UVA was like that. Getting to study with Gary Gallagher, Michael F. Holt, and Elizabeth Varon, and count among my peers many of the best young scholars in the field, was an incredible privilege. At a time when much of academic history stressed an approach that was theoretical, abstract, or driven by external political projects, UVA emphasized concrete knowledge about how systems in the past actually worked, what lives were like, and often helped keep many of the sillier fads at bay. There were challenges, to be sure, but it was an environment that shepherded young scholars into deep research and direct engagement with the past in a way I continue to benefit from.

JW: Give us a sense of what electoral politics looked like in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. This is a key part of the story you tell in The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century (2016).

JG: My work really began with one simple statistic: the turnout rates for eligible voters. I think many people assume America’s political past was basically staid and dull before maybe the 1960s or so. I know I used to. So I was fascinated to learn of a vibrant, vital, messy political world in our deep past. From the 1840s through 1900, roughly 80% of eligible voters participated in elections. What was their story? What was happening in the culture that sustained that engagement? What were the human lives that came together to make that statistic? I was fascinated to discover an expansive world of voters and non-voters who made partisan political combat one of the largest, loudest, most ubiquitous elements of our national culture. This was, to be sure, a system rife with racism, sexism, and other exclusions, but even with those limitations, diverse Americans were participating, voting, arguing, and fighting about politics. And they were often doing so in ways that were material, colorful, physical, and spectacular—perfect for the Smithsonian’s collections.

I became fascinated by the multiple paradoxes of this: a system that was both deeply bigoted and among the most democratic in world history; a mixed use of the same cultural institutions to disburse government power, settle ideological debates, and also entertain millions with marches, barbeques, fireworks, booze, and brawling. I loved the combination of seriousness and silliness that drove it all.

And young people were the fundamental fuel, both participating in politics for personal reasons, and being recruited by predatory campaigns who coveted their votes. And then, just as fascinating: the era ended with a crash in turnout after 1900, a dramatic quieting of politics, and a falling away of new, young voters. What was that about?

JW: Your next book, The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865-1915 (2021), really delves into that question by examining how reformers in the Progressive Era tamed the system to give us what we might think of as “normal” politics. Tell us about that.

JG: That book was an attempt to get three not-well-known stories into the public conversation. The first was the mix of engagement and enragement that drove politics in the second half of the nineteenth century. After the 2016 election, many contemporary observers kept throwing around words like “unprecedented” when talking about politics, seemingly unaware of how heated American democracy had been during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. If contemporary observers had any sense of political conflict in our past, it was from the Civil War, but turnout and partisanship actually increased in the generation after the war was over (1876–1896). So there was a lot of great material there, from a colorful age, that people just didn’t know. Also, twenty-first-century observers kept wondering where our “normal” politics had gone, missing that many of our norms were constructed in the early twentieth century to reign in that earlier, wilder era. So we had this deep history that was relevant to our contemporary struggles, and few non-historians knew it. Just telling that story felt urgent.

The second element was trying to avoid a simplistic, brittle view of our evolving politics as either good or bad. I think people were throwing around the term “democracy” without considering the hard trade-offs inherent to that system. At least in U.S. history, our periods of greatest mass engagement coincided with our period of greatest ugliness, partisanship, fraud, and violence. And the subsequent crash in popular interest after 1900 led to the flourishing of incredible Progressive era reforms. So, were the laws establishing income taxes, direct elections of senators, women’s voting rights, clean food and drug laws, regulations of monopolies and railroads, and a host of voting reforms only possible because a big chunk of voters lost interest and stayed home? What does that say about the relationship between engagement and civility?

Finally, I believe that history is about people. You could make the two previous points from 30,000 feet, using statistics about American Political Development. But where’s the fun in that? Who wants to read that book all the way to the end? I was hoping to tell a not-well-known human story. So I hit upon the saga of congressman William “Pig Iron” Kelley and his daughter, the labor activist Florence Kelley. Both were major players in the struggles of their eras, from the 1830s into the 1930s, passing down a legacy across time. For Will Kelley, a mid-nineteenth-century man, that meant public, political efforts, bombastic campaigns, writing the text of the 15th Amendment, and many speeches and rallies. But for his daughter, who was operating as a woman in the early twentieth century, she had to rely on consumer boycotts, labor crusades, social science studies, the administrative state, and private influence and lobbying. Both had to operate in different ways in their different eras, highlighting the changes going on in American politics over this tumultuous, neglected period. Their adventures and campaigns helped chart the changes I was trying to show.

So that was the thinking behind that book. I think it all helped it connect with audiences, but getting those three plates to spin at the same time was not easy.

JW: After writing about the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, what led you back to the mid-nineteenth century to write a book about the Wide Awakes?

JG: The Wide Awakes had been stuck in my craw for decades. I learned about them in grad school, wrote a little article, and thought I was done. But just as the Wide Awakes used to show up at William Seward’s house, or Carl Schurz’s hotel, and get them out of bed demanding midnight speeches in the 1860 campaign, they kept coming back to me too. At the Smithsonian, people would contact me with new artifacts they’d found, questions about the movement, or plans to restart a group today. And then, in 2020 and 2021, as America debated public protest in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, the January 6 attacks, etc., the Wide Awakes’ blend of public politics and public militarism seemed especially relevant. If writing The Age of Acrimony was an intricate balancing act, writing about the Wide Awakes was just a delightful sprint. Their story was rich and well-documented, their movement had a clear narrative arc, and they hadn’t been written about before in a book. It was so much fun to go back to them after muddling through the Gilded Age and Progressive era history.

JG: The Wide Awakes had been stuck in my craw for decades. I learned about them in grad school, wrote a little article, and thought I was done. But just as the Wide Awakes used to show up at William Seward’s house, or Carl Schurz’s hotel, and get them out of bed demanding midnight speeches in the 1860 campaign, they kept coming back to me too. At the Smithsonian, people would contact me with new artifacts they’d found, questions about the movement, or plans to restart a group today. And then, in 2020 and 2021, as America debated public protest in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, the January 6 attacks, etc., the Wide Awakes’ blend of public politics and public militarism seemed especially relevant. If writing The Age of Acrimony was an intricate balancing act, writing about the Wide Awakes was just a delightful sprint. Their story was rich and well-documented, their movement had a clear narrative arc, and they hadn’t been written about before in a book. It was so much fun to go back to them after muddling through the Gilded Age and Progressive era history.

JW: Tell us about the origins of the Wide Awakes. How did they get started? And what caused their movement to spread across the country?

JG: One of the great things about the Wide Awakes is that, although they grew to be among the largest mass movements in American political history, their founders were basically just working class kids. A 19-year-old clerk in Hartford put together a cool uniform, and he and his friends formed a militaristic marching company. At first they were just hoping to sway a gubernatorial election in Connecticut in 1860, but much of the North was primed for a mass movement. Their uniforms, their marching, their public speaking, and their resistance to intimidation made them an incredible vehicle to fight the local and national forces of “the Slave Power” that had been suppressing anti-slavery views. And because of their modular, franchise model, they never all had to agree on the knotty constitutional issues about slavery. As long as they all wore the same uniforms and marched together, they could be an inspiring campaign movement. So these young novices in Connecticut kicked off a movement that would spread across the North, and into the West and even the Upper South. At their peak, they had hundreds of thousands of members. The exact number is hazy, but adjusted to today’s population, we’re talking about a movement of millions.

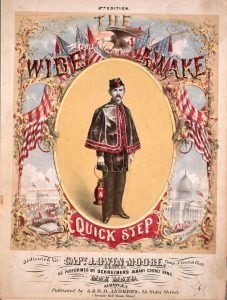

JW: I’ve always found the Wide Awakes’ symbolism fascinating. What can you tell us about their dress, the ways they marched, and the symbols they used?

JG: I agree, they’ve got to be among the most visually composed and compelling movements in American history. Like them or hate them, everyone was struck by their black, shiny capes, their militaristic caps, their torches on long poles, their use of the open eye as a symbol of awakening, and their coordinated marching. Some people found it inspiring, some people found it menacing, and some thought the whole thing looked awfully silly, but I really found no one who had no comment. And interestingly, they did spend much of their time, in their meeting minutes and in their company constitutions, laying out exactly how they wanted to look, down to the cut of their capes, the color of their lanterns, and the style of their marching. Many of their founders, and spreaders, were in the textile business and had an eye for design (and for sales). And they were connecting to a mid-nineteenth century culture, in the U.S. and Europe, that was passionate about uniforms and militarism. They looked to Garibaldi’s black poncho, Italian nationalists’ red shirts, and European revolutionaries’ use of flags in 1848. Interestingly, very few of the young, northern Wide Awakes had military backgrounds, so they kind of pieced together a pseudo-militaristic movement from scratch.

But it all came together to argue a material thesis: that the Republican Party was united, bold, and orderly at a time when many other parties seemed fractured or chaotic.

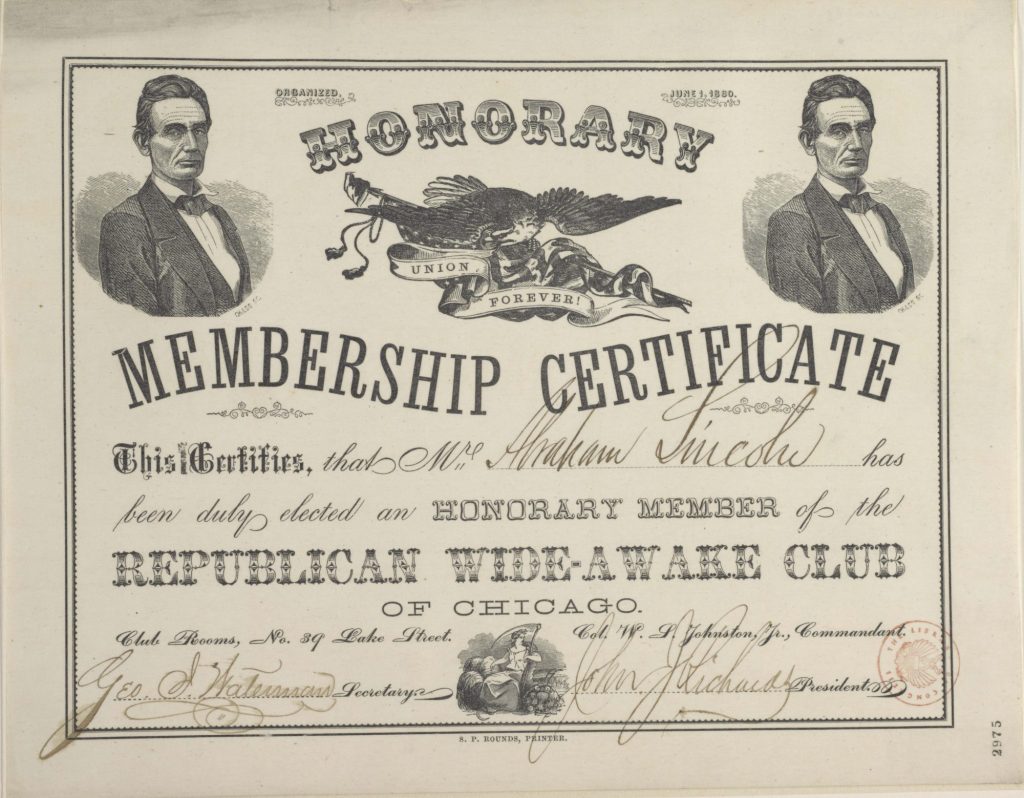

JW: What did Lincoln think of the Wide Awakes? Did he have any interactions with them?

JG: Lincoln stands out, among the Republican leadership, as being the least noisily pro-Wide Awake. He rode with them in their very first official march, but he was notably cautious about the movement. Other Republican leaders like William Henry Seward or Carl Schurz sometimes grumbled about the Wide Awakes waking them up or being too enthusiastic, but learned to play to the Wide Awakes, to speak to them and joke with them and to help spread and validate the movement. Some—like Frank Blair Jr., Hannibal Hamlin, John A. Andrew, and Charles Francis Adams Jr.—even joined the Wide Awakes or marched with them.

But Lincoln wrote privately that he found “monster meetings” basically silly, a side-show to the real campaigning of buttonholing individual doubtful voters. As a nominee, he was expected not to campaign, so he was insulated from having to please crowds of Wide Awakes. Once he won the election, he said nice things about the movement, but also basically implied it was done. Through lieutenants like John Hay and William S. Wood (who organized his trip to Washington), word was put out that Lincoln wanted the Wide Awakes to go away. Meanwhile, Seward and Sumner and all the other party leaders were cheering the Wide Awakes. It’s an interesting disjuncture.

JW: How did the South react to the Wide Awakes?

JG: Just as the Wide Awakes’ whole ethos seemed designed to excite young northerners, it was terrifying to many in the South. The movement just confirmed southern talk of northern coercion, northern extremism, and a northern majority using its numerical advantage in menacing new ways. And many southerners noted that the clubs emerged from Connecticut, John Brown’s home state, just a few months after his famous raid. To many, they symbolized a national, partisan escalation of what Brown had been plotting. Brown’s force had just 22 men, but the Wide Awakes were rallying hundreds of thousands.

Many in the South also lived in a limited news environment, getting only southern papers or extremely biased northern ones (like the New York Herald). Many honestly believed that the Wide Awakes were a paramilitary force, preparing to invade the South, spark a race war, and kill white southerners. The existence of some African American Wide Awakes in Boston further agitated them. And, if we’re trying to be as empathetic as possible with people in the past (without agreeing with them), how could your average newspaper reader in Huntsville or Shreveport know the truth, that the Wide Awakes were not military but really just interested in campaign spectacle?

The response to the Wide Awakes was proof of how damaged the bonds of Union already had become. And many secessionists made use of this, referencing the Wide Awakes as they campaigned for disunion. Some people (who really could have known better), like ex-governor of Virginia Henry A. Wise, went around telling crowds that the Wide Awakes would soon invade, and that if southern states did not secede, they would be “cut to pieces by the Wide Awakes.”

While a much larger conflict led to secession, the Wide Awakes became a concrete device to help make disunion happen.

JW: What became of the Wide Awakes after the election of 1860?

JG: This was one of the most fascinating elements of their story, and one of the best things about returning to the Wide Awakes after years away. Previously, I’d assumed that the movement petered out after Lincoln’s victory in November 1860. But as I dug back in, I learned that something much more dynamic and dramatic happened. Many clubs disbanded, but others hardened, reorganized as militias, some armed, others wrote to Lincoln offering to fight as his bodyguards or even invade the South.

At a time when southern states were seceding and arming, the Wide Awakes presented Republican leaders with a fascinating dilemma. They had this movement of hundreds of thousands of uniformed, (semi-)trained, excited young men. They could easily be turned into an army, or a kind of guard for Lincoln. In St. Louis, the Wide Awakes were already arming, training, preparing for a fight. But Lincoln and other leaders saw that while the Wide Awakes could provide muscle, they could also alienate much more important elements of the coming fight. Northern Democrats, southern Unionists, Border States still on the fence, none of them would be happy to see the Wide Awakes emerge as a partisan, paramilitary fighting force. So the movement was encouraged to disband. Outside of St. Louis, most did so, although many enlisted in the Union army en masse after Fort Sumter. In St. Louis, many Wide Awakes re-organized as Unionist militias and led the fighting at Camp Jackson in May 1861, fully evolving from a campaign club into a fighting force.

But in between the November election and the start of real fighting in April and May 1861, the Wide Awakes were caught in this tenuous, tentative space, between politics and war.

Finally, after the war was over, many ex-Wide Awakes emerged as key leaders in the Republican Party and in Gilded Age society. Some kept marching, holding reunions and rallies in the early twentieth century, although they really lost their edge over the years. By the twentieth century, they were mostly forgotten or neglected . . . which is what made it so much fun to help bring them back.

JW: Now that you’ve wrapped up this fascinating book, what are you working on next?

JG: I’m still in the very early phases of a new project. But I’m thinking about doing a book on political bosses across American history. People know the term “boss,” and often you’ll hear explanations for how things were different “back when the bosses ran things.” But to me, that hints at a rich world to explore. And the model of boss politics, in which leaders coordinated votes of anxious, resentful populations into blocs, often in opposition to the courts and rule of law, has relevance today.

Plus, their stories are amazing, from Boss Tweed to Mayor Daley and all the forgotten figures in between. I like to work on topics which have an old, neglected secondary literature to re-animate, and just a bit of public knowledge to try to expand upon. Plus, it’d be fun to move from across time, from the 1860s to the 1960s.

But I don’t want to jinx it, so no more on that one for now.

JW: That sounds fascinating! Thank you so much for joining us.