An Interview with John Marszalek on Henry Clay, Lincoln’s “Beau Ideal” of a Statesmen

Sara Gabbard: Please explain Clay’s early legal representation of Aaron Burr. Did the relationship cause him later regret?

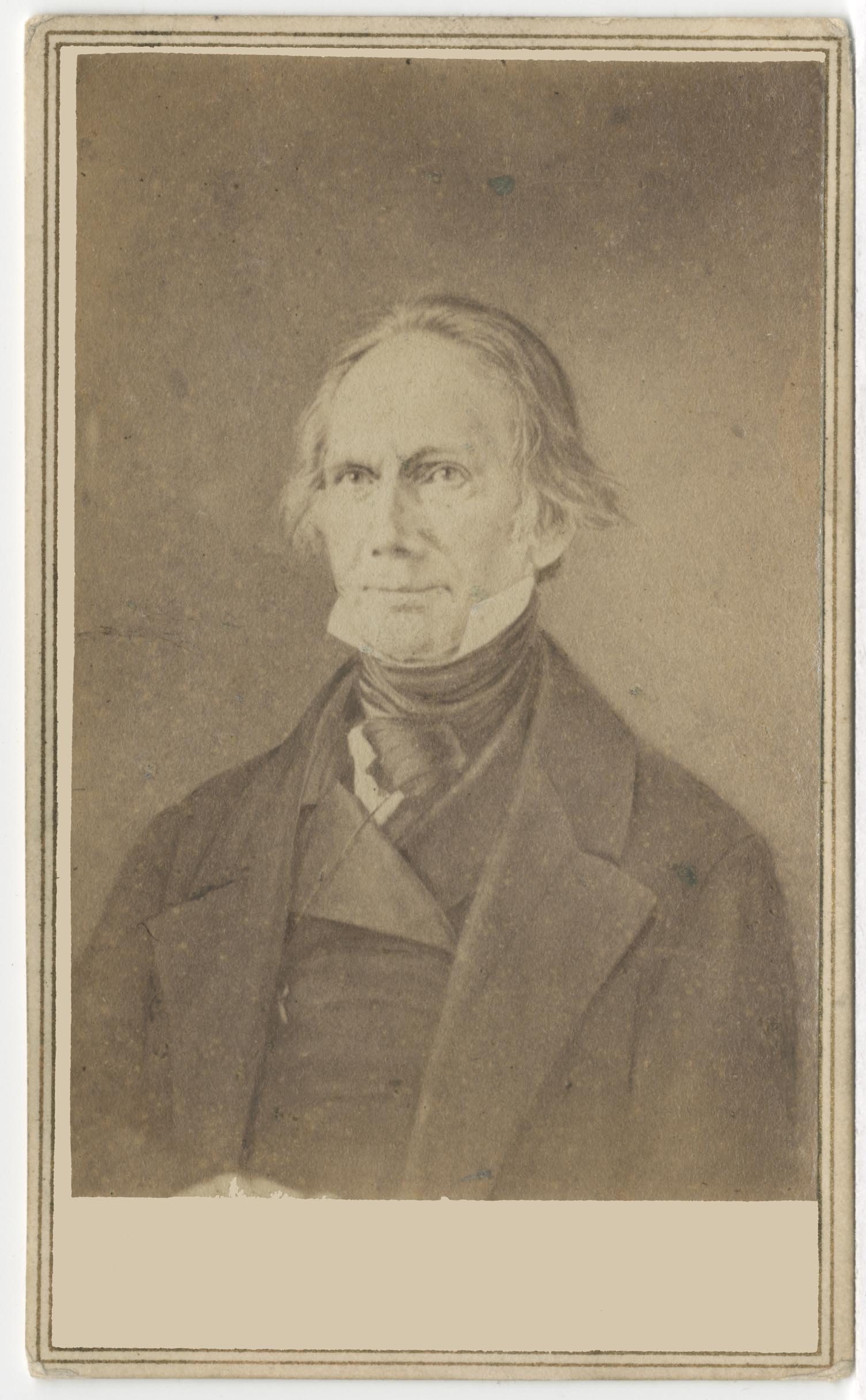

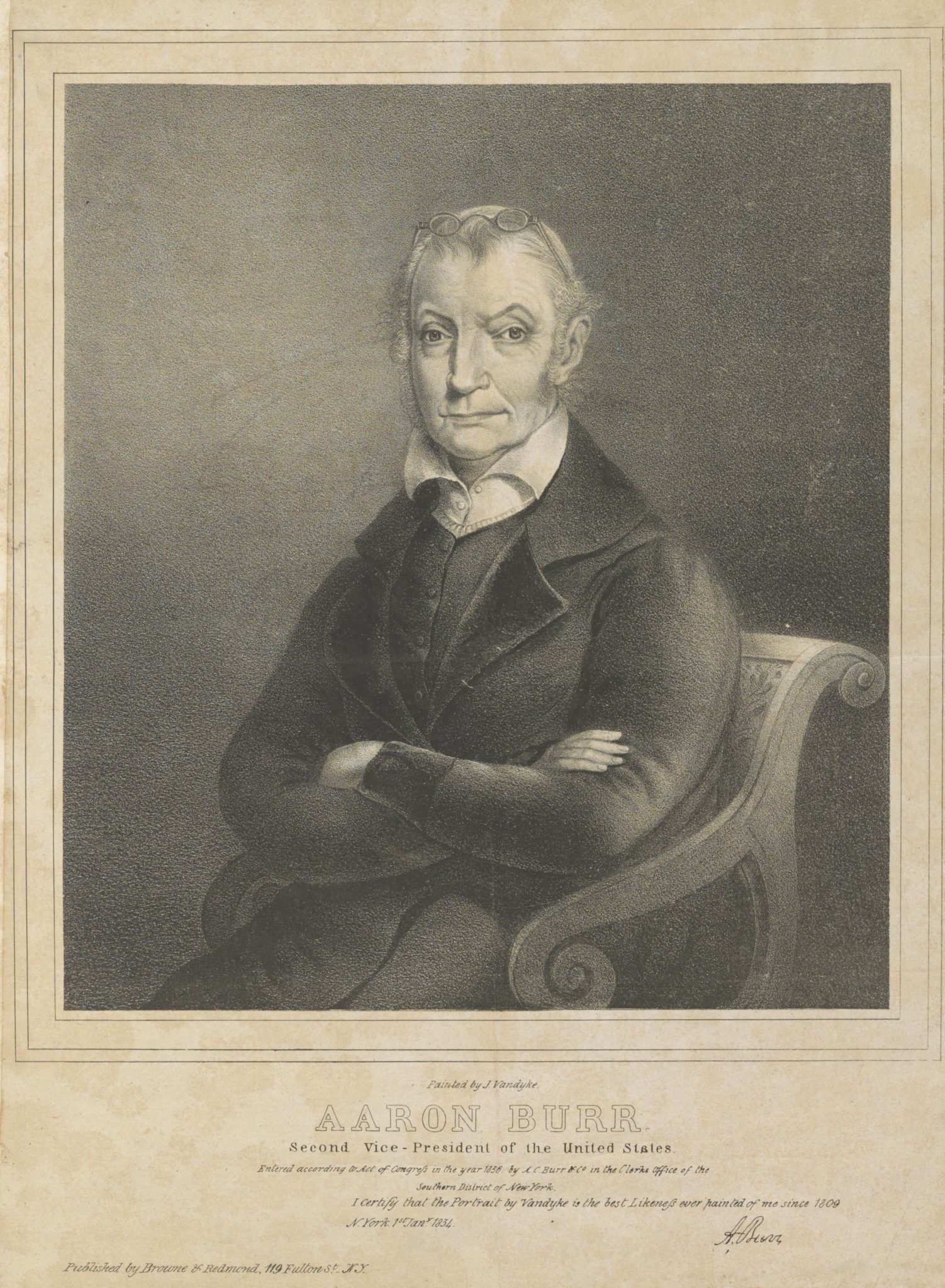

John Marszalek: In the early 19th century, Henry Clay and Aaron Burr were both young up-and-comers in American politics. Yet, Clay became one of the most famous of all 19th century Americans, while Burr never lived down the accusations that he unfairly killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel and later tried to incite a conspiracy against the stability of the United States. Clay was seen as the symbol of the Union, while Burr has come down in history as someone who tried to destroy it.

In late 1804 Burr resigned his place as Thomas Jefferson’s vice president because he worried about being found guilty of murder for killing Hamilton in a July 11 duel. This occurrence and his ability to alienate a wide variety of people caused him to travel to the West, rather than remain in the East. People in the West liked him, so they readily listened to him talk about the “grand expedition” of splitting off the West from the rest of the United States.

Burr had met Henry Clay in Lexington, Kentucky, and the latter agreed to defend him in court. A newspaper owned by Supreme Court Justice John Marshall accused Burr, even Clay, and a large number of other Democratic Republicans in the West of treason. Henry Clay then decided not to defend Burr because he had just been elected by his state to the US Senate. But then he accepted Burr’s offer to pay him more to stay on, and he even signed an oath swearing his innocence. Clay stayed on.

When Clay traveled to Washington and found that Jefferson’s supporters hated Burr as much as the Federalists did, he began to worry. Then President Thomas Jefferson showed him a letter which he said proved Burr’s guilt, and Clay believed him. He now saw Burr as being guilty as charged. He never forgave Burr for what he was now convinced was Burr’s lie. In 1815, the two men accidentally met, but Clay, still angry, refused to shake hands with his former client. They never met again. Clay’s legal involvement with Burr resulted in his being implicated in the controversy when he later ran for the presidency. Henry Clay, one of American’s great politicians, paid the price for his refusal to see the danger his political connection with Burr would cause him.

SG: What was Clay’s role at the Treaty of Ghent?

JM: Henry Clay earned the nickname “War Hawk” for his leadership of those congressmen of similar philosophy hoping to lead the United States into the “War of 1812.” When the war came to an end, however, he, along with four other Americans: Albert Gallatin, John Quincy Adams, Jonathan Russell and James A. Bayard, was named to the peace commission. Along with British commissioners, these Americans brought the War of 1812 to an end: actually to the “status quo antebellum.” As a war hawk, Clay had pushed for the desires of the West. At Ghent he forthrightly opposed John Quincy Adams and Eastern interests and refused to go along with giving England the right to navigate the Mississippi River in return for fishing rights for easterners. He also opposed giving England any rights to deal with the Indians in the West.

SG: Clay’s relationships with so many national leaders offers almost a mini-US history class: Please comment on his experiences with and feelings about (the following).

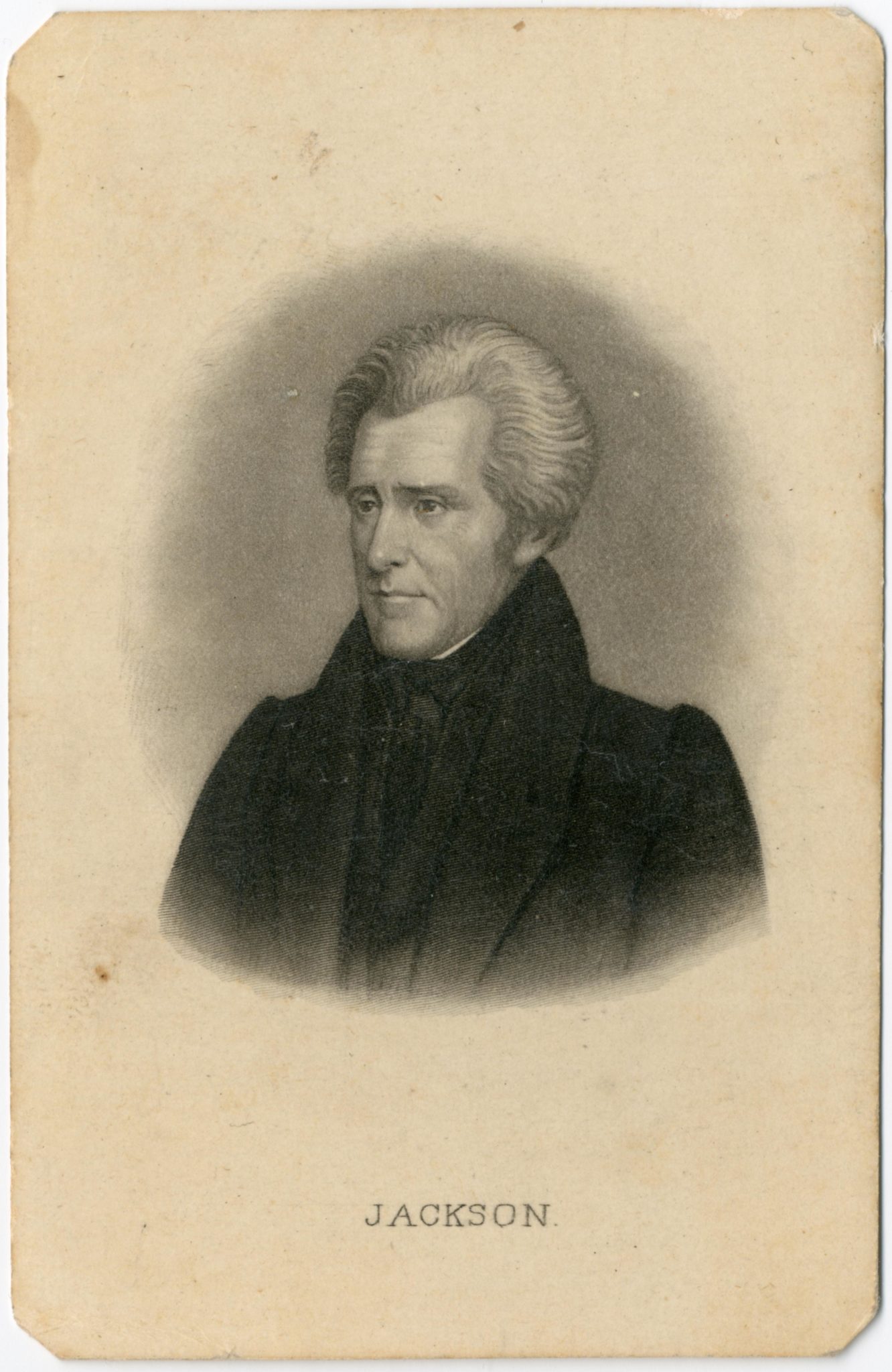

JM: John Quincy Adams – Henry Clay served on the Treaty of Ghent negotiations commission and stood in opposition to John Quincy Adams’ defense of easterners. Later, however, during the presidential election of 1824, he ended up throwing his support to Adams, allegedly, for receiving the post of secretary of state in the New Englander’s cabinet. One of his opponents, Andrew Jackson whom he would battle for almost the rest of his life, called the agreement “the corrupt bargain,” and hung it around Clay’s neck for the rest of his political career.

John C. Calhoun – John C. Calhoun was another war hawk, but coming from South Carolina he was hardly the nationalist that Clay was. The result was that, although they were allegedly in the same party, the two men were in constant conflict. Clay and Calhoun contested the so-called “tariff of abominations” by fighting over the right of nullification. Their different beliefs resulted in their opposition to one another, yet their mutual opposition to Andrew Jackson remained even stronger.

Andrew Jackson – Like Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson was one of the leading figures of the early 19th century. Actually, Jackson was more successful because he was twice elected president of the United States, while Clay ran three times and lost each time. Clay was a great orator, philosophical rather than straightforward, and a leading member of the House of Representatives and US Senate. Jackson was a famed military leader and appealed to the masses of Americans. Jackson was a great opponent of the Bank of the United States, while Clay supported the concept as part of his American System. Clay was the “Great Pacificator,” while Jackson took forthright stands on a variety of the era’s issues. Jackson and Clay were both important contemporaries, but they were poles apart in their attitudes.

James Madison – The major difference between James Madison and Henry Clay was their completely opposite stands on the desirability of war between the United States and Great Britain. Madison opposed war, while Clay called for it. During the war itself, the two men stood shoulder to shoulder, determined to defend the nation they both supported, although in different ways.

James Monroe – Henry Clay had many claims to fame; one of the most important was his support for what came to be called “the American System.” Clay espoused federally financed internal improvements like canals and roads, a high protective tariff, and later a Bank of the United States. In addition, Clay wanted to make the United States the leader of the nations in the western hemisphere, i.e. Latin America. As a Democratic Republican, Monroe opposed a federal role in American economic life and opposed an American role in Latin America.

John Randolph – In 1826, John Randolph was on the floor of the US Senate and called President John Quincy Adams and his secretary of state Henry Clay, a “puritan with the black leg.” What made this comment so awful was that “black leg” was a fatal disease which affected livestock. Clay was insulted and forgetting that Senators could say awful things on the floor of that body without fear of being called to account, challenged Randolph. The Virginian remembered the exception, but refused to tell Clay about it. He decided instead that he would not fire at his antagonist. This meant that Clay would certainly kill Randolph. When the two men fired on one another, Clay missed (accidentally) and Randolph (on purpose). It now came time for the second shot, and Randolph simply fired in the air. Clay then stopped the duel, and the two men left the field of honor unscathed and friendly again.

SG: What do you consider to be Clay’s great accomplishment(s) as Speaker of the House?

JM: Henry Clay played a major role in changing the power of the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from simply deciding what bills came up at what time, and, instead, increasing the Speaker’s political power. The result was that the Speaker of the House became much more powerful than the majority leader in the Senate. What the Speaker did was to look at the bills that were pending and assign them to specific committees, the members whom he had himself appointed. He also controlled the time for debate and made sure that he retained the right of the speaker himself to speak whenever he wished, by turning the House into a committee of the whole. Significantly he made all such changes in a way that did not seem to alienate the members and they went along with him. It was no accident that he was Speaker of the House for a total of ten years, the longest tenure of any 19th century Speaker.

SG: The topic of slavery obviously cast a giant shadow over the era of Clay’s political life. What were his feelings on the subject?

JM: Henry Clay did not approve of slavery, although he owned slaves himself. He opposed abolition because he saw it as a danger to the continuation of the Union, but he found slavery to be abhorrent. So, he found himself in the throes of a dilemma. He tolerated the institution in order to preserve the Union. His method of getting around this problem was to support the concept of colonization. The best way to end slavery and preserve the Union, he believed, was through his leadership of the American Colonization Society. Purchase freedom for American slaves and then send them back to Africa where they might live a decent life. In fact, colonization did not work, but Clay saw no other way to handle the matter.

SG: Henry Clay was determined to become President. Why did he fail? At what time was he closest to achieving his goal?

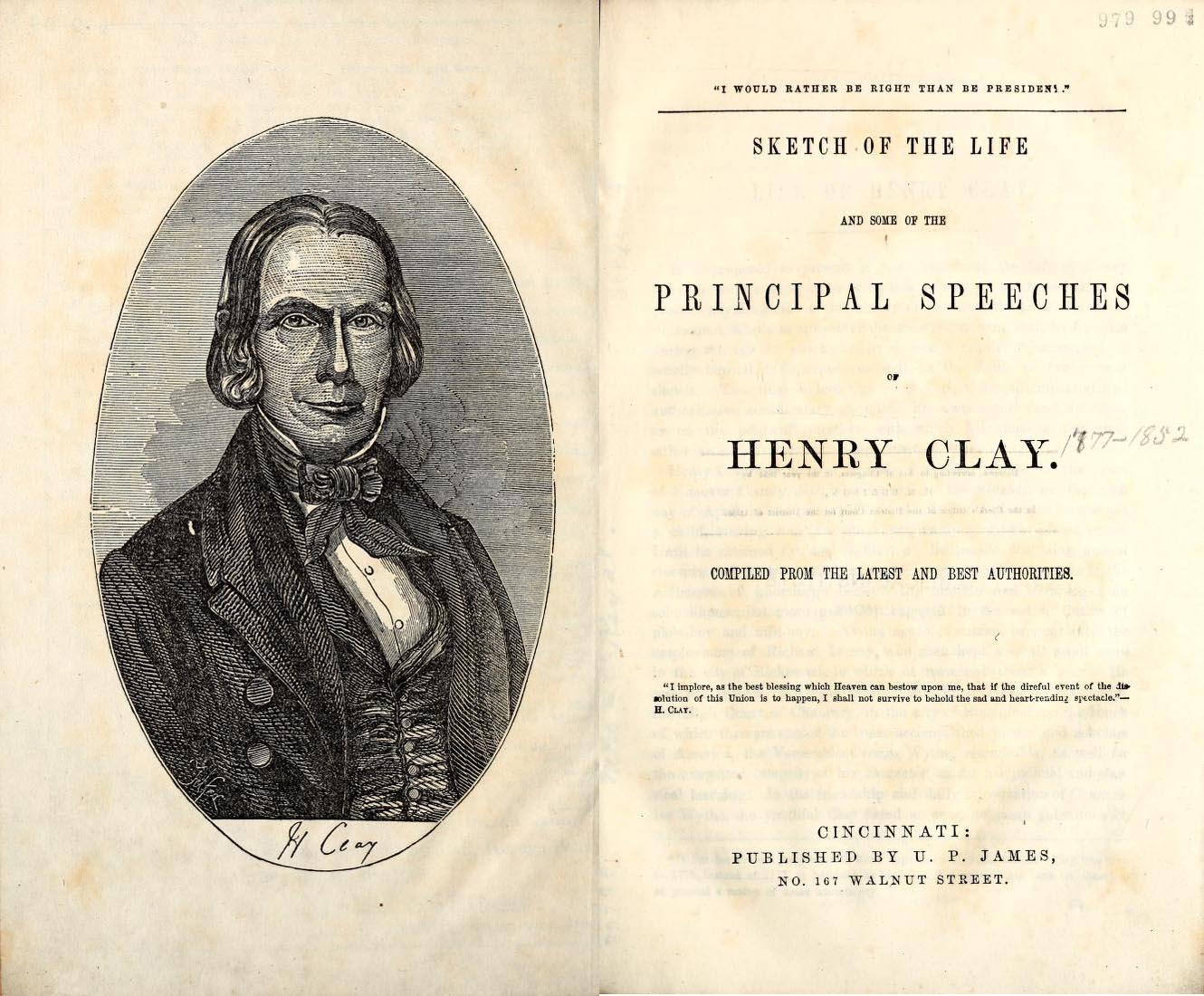

JM: Henry Clay ran for the presidency in 1824, 1832, and 1844. He failed each time. He said in 1839 that “I would rather be right than president,” but, in fact, he did want very badly to hold the nation’s highest office. He was the

country’s leading Whig and nationalist. He strongly supported his American System. This was, indeed, one of his problems: he took firm stands in favor of a strong central government, at a time when Andrew Jackson was extremely popular and a believer in state rights. Clay was called “Harry of the West,” but his nationalistic positions were more eastern than western. So, Jackson became the candidate of the West, and bypassed Clay. In 1844 Clay came the closest to victory, but he uncharacteristically made a political faux pas when he wrote the so-called “Raleigh Letter” opposing the annexation of Texas because it might result in war with Mexico. Then he wrote two “Alabama Letters” seemingly changing his mind on Texas annexation. This flip-flop probably resulted in James K. Polk’s narrow victory. After this, Clay never ran for president again. He died in 1852.

SG: Probably not a fair question, but please give your overall assessment of the life and career of Henry Clay.

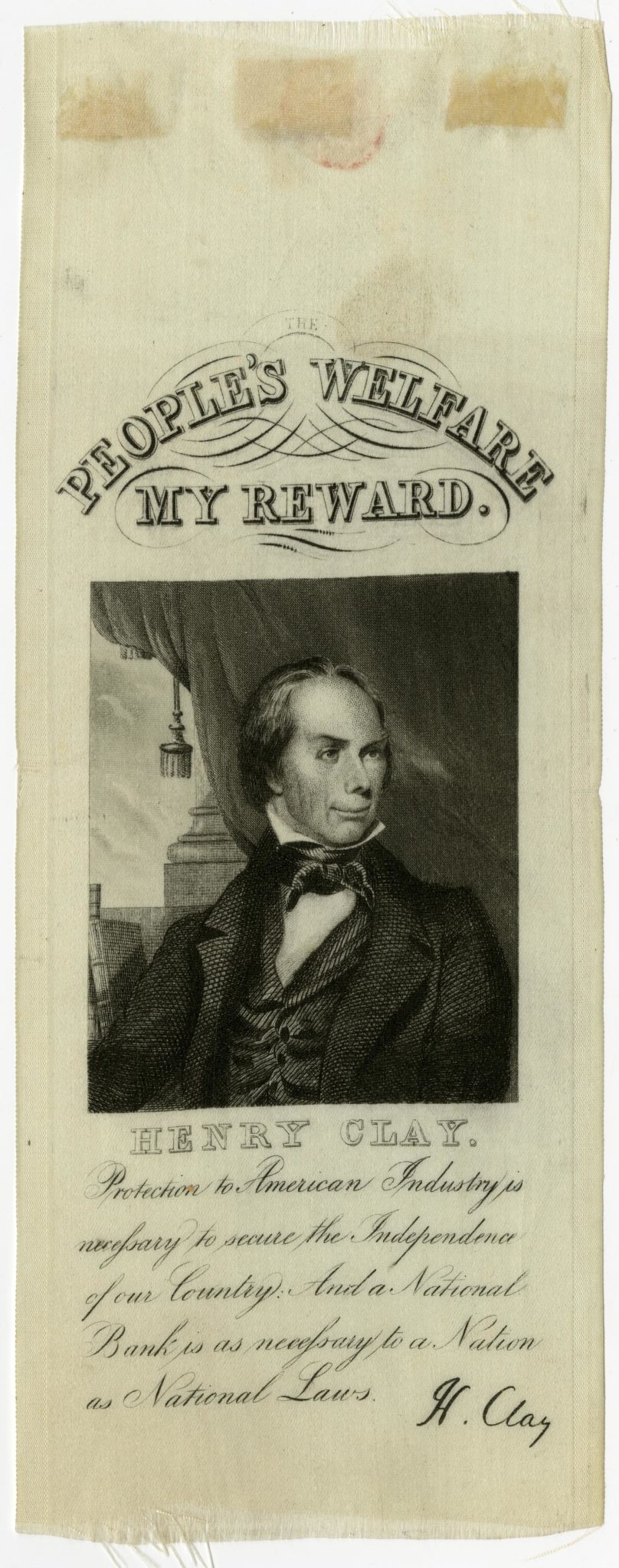

JM: Henry Clay was indeed one of the most significant politicians in all of American history. Consider his career: he was born in 1777 in Virginia during the American Revolution. He moved West to Kentucky and was one of the most significant attorneys of his era. He was a War Hawk, and a commissioner during the Ghent Treaty negotiations after the War of 1812; he was a powerful orator, and, established the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives as a national leader. He became a hero in Latin America, gained the nickname “The Great Pacificator” for his work on the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise Tariff of 1833, and the Compromise of 1850. He ran for presidential office three times. And, perhaps, most importantly, he had a tremendous influence on the man usually considered the greatest president in American history: Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln came from a Whig political background, so he naturally placed Clay on the highest pedestal. At one time, he called Clay “My Beau ideal of a Statesman.” Another time, he said that he “almost worshipped Henry Clay.” Lincoln never met Clay personally, but he heard him speak at least once; he voted for him, and in 1844 he not only campaigned for him, but he served as his elector in Illinois. When Lincoln ran for office himself, he frequently quoted Clay in his speeches. In his famous debates with Stephen A. Douglas, he quoted clay 41 times. The most famous connection Lincoln had with Clay was his eulogy of the man in Springfield, Illinois, upon Clay’s death in 1852. It was not his greatest speech, but its praise of Clay is obvious. He said: “our country is prosperous and powerful; but could it have been quite all it has been, and is, and is to be without Henry Clay?” He certainly did not think so.

[John Marszalek is the Giles Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Mississippi State University]