An Interview with Callie Hawkins

An Interview with Callie Hawkins

by Jonathan White

Callie Hawkins is the CEO and Executive Director of President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C., where she previously served as Director of Programming. She is responsible for innovative leadership of the national monument and for providing overall direction for all aspects of operations. Additionally, she co-hosts Q&Abe, the site’s award-winning podcast, which has reached thousands of people in more than 80 countries. During her tenure, Hawkins has spearheaded projects that won national and international recognition, including awards from the American Association for State and Local History, the American Alliance of Museums, the National Council on Public History, and a presidential medal in 2016 for Students Opposing Slavery, a youth education program for high school students dedicated to raising awareness about modern slavery. She has contributed to numerous publications, including the Journal of Museum Education, The Public Historian, and History Matters.

Jonathan White: I’ve visited Lincoln’s Cottage a number of times over the past twenty years and I always find it such a beautiful, peaceful place amid the hustle and bustle of Washington, D.C. Tell us about the history of the Cottage. And what did it mean for the Lincolns?

Callie Hawkins: President Lincoln’s Cottage is located on the outskirts of D.C.—about 4 miles uphill from the White House—on the grounds of what is today called the Armed Forces Retirement Home. The Cottage itself was built in the 1840s by a prominent Washingtonian, George Washington Riggs, who sold the property in the early 1850s to the federal government, which was looking to establish a retirement home for veterans. The Old Soldiers’ Home—as it was originally called—made a practice of recruiting high-ranking government officials to stay in houses on the property. While president, James Buchanan stayed in a house adjacent to the Cottage, and it’s likely that he is the one who made President Lincoln aware of the serene grounds.

The Cottage and the Soldiers’ Home grounds bookend Lincoln’s presidency—he visited days after his first inauguration and was seen riding the grounds the day before his assassination. The Lincoln family made plans to come to the Cottage for his first hot season as president, but the outbreak of the Civil War persuaded him to remain at the White House. By the next summer—the summer of 1862—the first family was desperate for a measure of comfort. Their beloved boy Willie had died in February, and the Executive Mansion was a house of pain for the first family. Mary never entered the room where he suffered again. In a May 1862 letter to Julia Ann Sprigg, Mary wrote, “Our home is very beautiful, the grounds around us are enchanting, the world still smiles & pays homage. Yet the charm is dispelled—everything appears a mockery, the idolised one, is not with us, he has fulfilled his mission and we are left desolate.” She noted their plans to move “to the ‘Soldiers’ Home,’ a very charming place 2 ½ miles from the city.” At the Cottage, the Lincolns found some of the quiet they craved. The quiet of a country cottage called to them in their deep grief. The Lincoln family returned each summer and early fall he was president; in total, Lincoln spent a quarter—or 13 of the 50 months of his presidency—in residence at the Cottage.

JW: What was daily life like for Lincoln and his family during their summers on the outskirts of the city?

CH: Given the seclusion of the Soldiers’ Home grounds, it’s easy to imagine the Cottage as a retreat. However, the constant call of visitors that President Lincoln experienced at the White House didn’t stop just because he’d moved out of the city. As Mary Lincoln described in a letter to friends, each day brought cabinet members, allies, and adversaries who wanted an audience with the president. The family was also surrounded by the veteran residents of the Old Soldiers’ Home and the young men from Company K of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteers, who guarded President Lincoln and his family both at the Cottage and at the White House.

Still, there were precious moments of peace that were difficult to come by at the White House. As Mary described, when the family was “in sorrow, quiet is very necessary to us.” The Cottage and the grounds offered a bit of that quiet they craved.

JW: You’ve been at the Cottage now for more than fifteen years. How has your role at the site evolved over time?

CH: I first started as the Education Coordinator—managing the tour and field trip programs—shortly after the Cottage opened to the public for the first time. As the vision for the Cottage grew, so did my role. After several years, I was promoted to Director of Programming. I spearheaded many groundbreaking programs, partnerships, and exhibits in order to expand our understanding of both Lincoln and ourselves. In August 2023, I was invited to serve as the CEO and Executive Director. While leading the organization was never really in my plans, the opportunity was hard to resist. We have the most talented, curious and brave staff, and it is a real honor to work alongside them.

JW: Tell us about some of the more moving or poignant moments of Lincoln’s presidency that happened at the Cottage.

CH: More than any one story or singular event, the most poignant parts of Lincoln’s time at the Cottage—to me—are revealed in all the ways he was human at this place. Here, he grieved; spent sleepless nights; responded to desperate favor-seekers in ways he later regretted; played games; read books and recited poetry; and made nation-changing decisions—he developed the Emancipation Proclamation in an upstairs bedroom—all within these walls. And, by choosing to talk about all the ways Lincoln was so uniquely himself at this place, President Lincoln’s Cottage gives visitors today an even more intimate look at a man about which we know so much. I’m constantly heartened by the comments we receive from self-professed Lincoln-lovers who share that they’ve studied the man their entire lives and feel closer to him after a visit to this place.

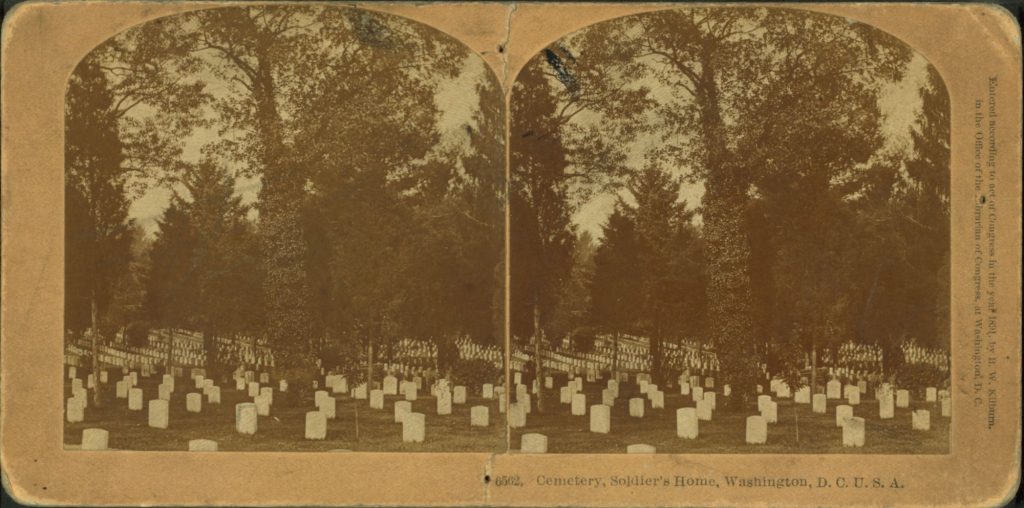

With that in mind, Lincoln’s most poignant moments at the Cottage to me are the ones that reveal different aspects of his character and humanity. One of those is an account we have from a California woman who wrote about seeing the weary president wandering through the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery, which was the precursor to Arlington. She wrote that “in the graveyard near at hand there are numberless graves—some without a spear of grass to hide their newness—that hold the bodies of volunteers. While we stood in the soft evening air, watching the faint trembling of the long tendrils of waving willow, and feeling the dewy coolness that was flung out by the old oaks above us, Mr. Lincoln joined us, and stood silent, too, taking the scene.” According to the woman, Lincoln softly recited several lines from the eighteenth-century poet William Collins: “How sleep the brave, who sink to rest / By all their country’s wishes blessed.” To what extent the site of those fresh graves influenced his wartime policies, writings, or speeches, we will likely never know. What is certain is that, in many ways, living at the Soldiers’ Home brought Lincoln closer to the war and its devastating toll.

I also find poignant the quiet moments the first family spent here with each other, especially Lincoln and his son Tad. By all accounts a somewhat permissive father, I adore the stories where we see glimpses of Lincoln, the doting father. Often mischievous and always full of love, these tales include everything from Lincoln climbing a tree to release one of Tad’s peacocks who’d become entangled in branches to playing checkers with his son on the south veranda and worrying over the whereabouts of Tad’s beloved goats who had mysteriously disappeared while Mrs. Lincoln and Tad were traveling. While none of these happenings would have made national headlines, they obviously meant something to the people who witnessed these micro-moments and jotted them down or passed them on through family stories of their own.

JW: You recently created an exhibit on grief. As readers of Lincoln Lore know, Lincoln was no stranger to grief, having lost his mother, father, sister, an infant brother, his sweetheart, and two sons—not to mention close friends and associates like Edward D. Baker and Elmer Ellsworth, and so many other dead during the Civil War. Tell us about this exhibit. And how did it come about?

CH: The Lincolns’ impetus for moving to the Cottage had been part of our tours since opening to the public in 2008. However, our initial approach focused more on Willie’s death as a circumstance that led them to this place, rather than a turning point for the family. In truth, Willie’s death—and Eddy Lincoln’s death several years prior—changed the course and character of both Lincolns’ lives forever and it certainly impacted who they were at the Cottage. Early on, we failed to give that lived experience the care and attention it deserved. We also missed the opportunity to connect modern grieving people to this part of the Lincolns’ lived experience. For a site that really seeks to bring Lincoln into the present, the recognition that grief is a universal human emotion that every visitor who walks through our doors has or will experience if they love and live long enough, has provided new chances to deeply connect with modern visitors who may also be grieving.

In December 2020, President Lincoln’s Cottage opened Reflections on Grief and Child Loss—a special exhibit that puts the Lincolns’ experience with traumatic grief after the deaths of their children in conversation with nine modern families whose children have died. These families represent a range of perspectives and cultures, and their children have died inexplicably and as a result of illness, violence, and other tragic circumstances. While each experience is unique and individual, these families are connected—to each other and the Lincolns—in their grief and in their love for their children. At the center of the modest exhibit room is a large, structural weeping willow on whose branches hang dozens of removable vellum leaves. On each dangling leaf, visitors are invited to write the name of a child or other loved one who has died and hang the leaf back on the tree. This public memorial has resulted in thousands of messages of love and loss.

Reflections of Grief and Child Loss was also a labor of love for me very personally. On February 12, 2018—which also coincidentally was Abraham Lincoln’s 209th birthday—my infant son tragically and unexpectedly died. I now knew exactly what Mary Lincoln meant when she said something I had quoted a million times throughout my tenure at the Cottage, “When we are in sorrow, quiet is very necessary to us.” I had never fully appreciated that—and her—until then. In fact, in those early days, I remember thinking that if society did to me what it did to Mary Lincoln, then I might not survive the pain of such an enormous loss. For me, integrating my love for my son who died into every part of my life became vital to my own survival. I had a recognition that if I felt this way—isolated in society and deeply connected to the Lincoln story—then other people might find a measure of solace in this story, too.

To create the exhibit, we identified themes related to the Lincolns’ own grief from their private correspondence and from the reflections of those who knew them. From the historical record, themes emerged that became the basis for a series of questions on which we asked the participating modern families to reflect. By connecting the Lincolns’ experience to the reflections of contemporary families, we found commonalities and meaningful differences, especially related to places of meaning, support networks and social expectations, and rituals.

It’s probably no surprise, but one of the aspects of grief that echoed across the eras is the idea that places hold power in death and grieving. According to grief researchers, places crystallize memories of children who have died, create powerful connotations that inform the grieving process, and provide a space to reflect. Sometimes these places hold moments and memories to which we long to return, and others are places we would like to forget. As I noted earlier, the White House held both beautiful memories of Willie’s life and agonizing memories of his death. The Cottage offered a measure of quiet and an opportunity to nurture their broken hearts that they perhaps couldn’t find at the Executive Mansion. In our grief exhibit, a modern family echoed: “Our home is a place of beautiful memories and terrible pain. [Our daughter’s] bedroom has, for the most part, remained the same. We find comfort walking by her door and peering at her things just as we did when she was alive. She loved being outdoors and helping in the garden. Since her death, we have planted her favorite pink flowers and have garden art placed throughout that bears her name. We take pride in what we have created. It is a quiet space that allows building new memories but also remembering the old.” Her mom went on to share, “I personally cannot drive by any elementary school without thinking that if she went to that school, she would be alive. It seems like a cruel world when you have these unannounced reminders that your child died as you go about your life.”

In the exhibit, we acknowledge that grief is a universal experience. Yet, our society holds little space for the grieving, who often are left feeling isolated and alone. It is a profoundly personal experience, but is shaped by external factors, including the expectations of society and those closest to the bereaved. The type of support a person receives in the aftermath of their loss is critical to their ability to integrate their grief into their daily lives.

The historical record suggests that the Lincolns’ felt the weight of social expectation and longed for support from family and friends, though this manifested itself in different ways for the two of them. They shouldered public opinions, advice, duty, and criticism, even as they grieved. Society urged Mary to focus on her other children. But she went far deeper into mourning than others thought proper. She retreated from society for an entire year. Her grief fueled accusations she was mentally unbalanced. Mary experienced public outbursts and crying fits so intense that Abraham’s thoughts turned to the mental institution across the river. Unable to take time off or distance himself, Abraham was expected and required to go back to work. Not long after, he laid the groundwork for the Emancipation Proclamation. He had to face the war alongside his grief and carry the double burden of being the President of the United States and a grieving father, often reflecting in the country’s first national cemetery, located just a couple hundred yards from the front door of his Cottage. The Lincolns found support in old friends and family. And they found some perspective in the losses of those around them.

Once again, these sentiments were echoed by modern families who participated in the exhibit. Abby’s father reflected, “Talking about Abby is so vital to us in keeping her memory and legacy bright and alive. I think it is a surprise for some people that we still talk about her so freely. I think they are confused as to why we are still talking about her, assuming reflecting on her life, and death, only accentuates the pain. They don’t understand that talking about her is the best way of staying in touch with our continued love for her.” And Brendan’s parents acknowledged that the two of them often have very different needs from one another. His father expressed that, “The action of greeting people and accepting their sympathies helped me through Brendan’s funeral. It gave the people a way to express their support for me and our family. It recognized our connections and acknowledged that Brendan and our family had value.” By contrast, Brendan’s mother added, “So many people wanted to offer kind support, but this loss of my son is so entirely personal that I find little comfort from others. It’s in the time in bed before I sleep when I talk—sometimes aloud—to Brendan that I am comforted.”

When a loved one dies, researchers say that ritual “serves to honor the content of our hearts, both the love and pain.” Rituals like funerals and memorial services offer what Dr. Joanne Cacciatore—a leading research therapist and herself a bereaved mother—describes as “connection maintenance” by helping us feel closer to the one who has died. When a child dies, these rituals can honor the importance of the child in their parents’ lives and can heighten the ability of those close to the grieving—who may also themselves be grieving this loss—to show up for the bereaved parents in meaningful ways that validate rather than diminish their loss.

On February 24, 1862, a storm swept through Washington, D.C., that was so fierce it knocked out windows and toppled church steeples. Inside the Executive Mansion, Abraham, Mary, and Robert Lincoln gathered in the Green Room to bid a private farewell to their beloved boy who had died days earlier. They arranged flowers in Willie’s hands and draped the mirrors in black. Neither Mary nor Tad, the Lincolns’ youngest son, attended the funeral. Mary was too distraught, and Tad was bedridden with the same illness that killed his brother. Abraham and Robert, the oldest of the Lincolns’ four boys and the only one who knew all of his siblings, attended the service and processed with his casket to a Georgetown cemetery where Willie was laid to rest in the Carroll family vault, beside the Carrolls’ own departed children.

In the exhibit, one family reflected on the immediate aftermath of their daughter’s death and her funeral, saying: “The days immediately following [our daughter’s] death were held together by close family and friends. They protected us. They allowed access only to close friends and kept strangers and the media away. We tried to personalize the service by singing our daughter’s favorite songs and sharing funny stories, but it did little to alleviate the trauma. Distraught, my husband and I chose to allow other family members to eulogize her. It is one of our biggest regrets.”

As we heard over and over again from grieving families, rituals serve to keep parents connected over time to their children who have died, as Jaycee’s mom reflected, “I find ways that I can share my Jaycee moments with others. Sharing photos and stories of Jaycee. I still parent my child (young adult) by letting people know his personality. I end my emails from the two of us, and I use the word ‘is’ instead of ‘was.’”

JW: What was the public reaction to Reflections on Grief and Child Loss?

CH: Because grief is universal, the exhibit has been meaningful to tens of thousands of our annual visitors. People not directly impacted by child death report that its message is instructive for all types of grief and grievers. We have found our takeaway cards that provide suggestions on how to best support grieving loved ones are especially resonant. One visitor noted, “I loved this exhibit. Thank you so much for working so hard to find solidarity and community for everyone who has suffered the loss of a child and all of us who love them.”

We have also connected with a new audience of bereaved people in search of opportunities to share their experiences publicly in a grief-averse society. We’ve been so moved by the scores of grievers who pilgrimage to the Cottage to leave behind a memorial leaf. One grieving parent shared, “It was so comforting to see affirmation of the grieving we have lived through after losing our son.” But perhaps one of the most moving comments from a bereaved visitor was a note that simply said: “I felt less alone.”

This exhibit has been important to the parents who so graciously shared their reflections of love and loss. One mother explained the import of participating in this project, saying “When your child dies, you get no more moments where accomplishments are celebrated, or milestones achieved. With [my son] being part of this exhibit, I get to feel proud that he has a chance to make an impact, bring awareness and potentially create change.” To our great honor, bereaved parents, many of whom have traveled great distances, have chosen to spend the anniversaries of their child’s death or birth at the Cottage, memorializing them on a vellum leaf on the central willow. As the tree fills up, the Cottage team will transcribe the messages from each leaf onto seed paper and ultimately plant a grief garden on the Cottage grounds. An act which will, as reporter Gillian Brockell wrote in a piece for the Washington Post, take “all that love and grief and sustain something new and alive.”

For many visitors, a Google search of “famous people in history who have lost children”—tapped out on their phones while in the throes of deep grief—led to Brockell’s article on the exhibit, which ultimately led them to the Cottage. Desperate for community and connection, they find a measure of that on these grounds.

I wish this exhibit never had to be, yet I am grateful that a shared sense of love and pain have brought me in community with so many other loving people and families who so generously provided their reflections.

JW: What other things can visitors to the Cottage expect to encounter?

CH: Lincoln’s Cottage is perhaps the best place in the country to understand Lincoln as both a private man and president. I’m often struck by the deep human connection to Lincoln that visitors come away with. When people visit the Cottage, I hope they glimpse the view of downtown Washington that Lincoln had from his back porch—a view that gave him both the literal and figurative latitude to just think about things differently. I hope they will run their hands along the banister—the same one that provided stability for a war-weary and grief-stricken Lincoln as he made his way to bed each evening. And, I hope they will feel the “Lincoln shiver”—a full-bodied sensation that some people report experiencing when they walk through these rooms and think deeply about Lincoln and what his life and work mean to us today.

Our public programs further demonstrate how what happened here more than 160 years ago continues to ignite courageous new ideas and respectful dialogue. Annual programs like Students Opposing Slavery, the Lincoln Ideas Forum, and Two Faces Comedy—a partnership with the DC Improv—thematically link the history of Lincoln’s legacy at this place with modern audiences in unexpected ways. We also host annually Bourbon and Bluegrass as a nod to Lincoln’s Kentucky roots and a fundraiser for our preservation activities. Perhaps one of my personal favorite parts of our programming is Q&Abe—a podcast that explores real visitor questions. We always start with the Cottage and Lincoln but end up in some unexpected places. It’s a great tool for sharing this special visitor experience with audiences who may never get to visit the Cottage in person.

JW: Thank you so much for sharing your story with us, and for the work you are doing to connect modern families with this very important history.