A New Letter from William H. Herndon to Abraham Lincoln

A New Letter from William H. Herndon to Abraham Lincoln

by Jonathan W. White

On September 6, 1883, the Illinois State Journal ran an article describing how Lincoln’s third and final law partner, William H. Herndon, had tried to procure a patronage position early in Lincoln’s presidency. “Herndon went on to Washington City and asked for some office,” the article stated. “Lincoln wanted to do something for Herndon, but not to give him anything which would expose his weakness in the public service.” It concluded, “When he settled on what he would give him, Herndon, whose expectations had been raised very high, became dissatisfied, and returned to Springfield, and was very sour on Lincoln.”

Herndon was infuriated by this “untruthful” and “meanly treacherous” article. On September 22, he penned a letter to the editor offering his own account of his dealings with Lincoln when it came to patronage. According to Herndon, Lincoln had come into their law office shortly before he departed for Washington in February 1861 and said, “Herndon, do you want to hold any office under my administration?” to which Herndon replied, “No, Mr. Lincoln, I do not. I now hold the office of Bank Commissioner of Illinois and besides, I have a good practice in my profession; and if I take office under you, I will lose my practice and my present office.” Herndon pointed out that when he’d traveled to the White House in 1862 to discuss patronage matters, it was only to help a friend, Charles W. Chatterton. Herndon wrote in his 1883 letter to the editor: “I quickly got the office, ‘freely, without purchase; fully, without denial; and speedily, without delay.’”

In fact, there is a curious backstory to this trip that Herndon did not include in his 1883 letter. Herndon had recently lost his first wife and was a widower with a gaggle of children. He began pursuing Anna Miles, a beautiful young woman who was eighteen years his junior. As Herndon’s biographer David Donald writes, “Her older sister Elizabeth had some years earlier married Charles W. Chatterton, who wanted a federal job that would offer money and adventure. To please a prospective brother-in-law, Herndon volunteered to secure an appointment for him. In return, Chatterton and his wife would use their good offices in convincing Anna that Herndon would make an acceptable husband.” And so, in early 1862, Herndon helped secure Chatterton the appointment as Indian Agent for the Cherokee Agency. In return, Herndon got what he desired. Chatterton “immediately began to use his influence with Anna Miles,” as Donald put it, and her “reluctance crumbled” under “strong family urging.” The couple married on July 30, 1862.

In his 1883 letter, Herndon claimed that in 1863 he “again, for myself this time, asked Lincoln for an office”—but he did so, he insisted, in order to help another friend. According to Herndon, “Mr. Lincoln telegraphed me that he wished to give me an office, and mentioned what it was.” Herndon immediately replied that he would accept the position but then “sat down and wrote Mr. Lincoln that I could not accept the office,” and that he wished it to go to Lawrence Weldon, another attorney on the Eighth Illinois Judicial Circuit. “The reason why I telegraphed back to Lincoln just as I did, was because I did not wish anybody to know anything about our private affairs,” Herndon wrote in 1883. Further, he said, “it is my honest belief that Mr. Lincoln would have willingly given me any office that my ambition had struggled for.” For this reason, he insisted that there was no reason for him to “have a grievance against my best friend” or “be very sour against Mr. Lincoln,” as the Illinois State Journal article had intimated. Herndon wrote: “He gave me everything I wished for and asked for.”

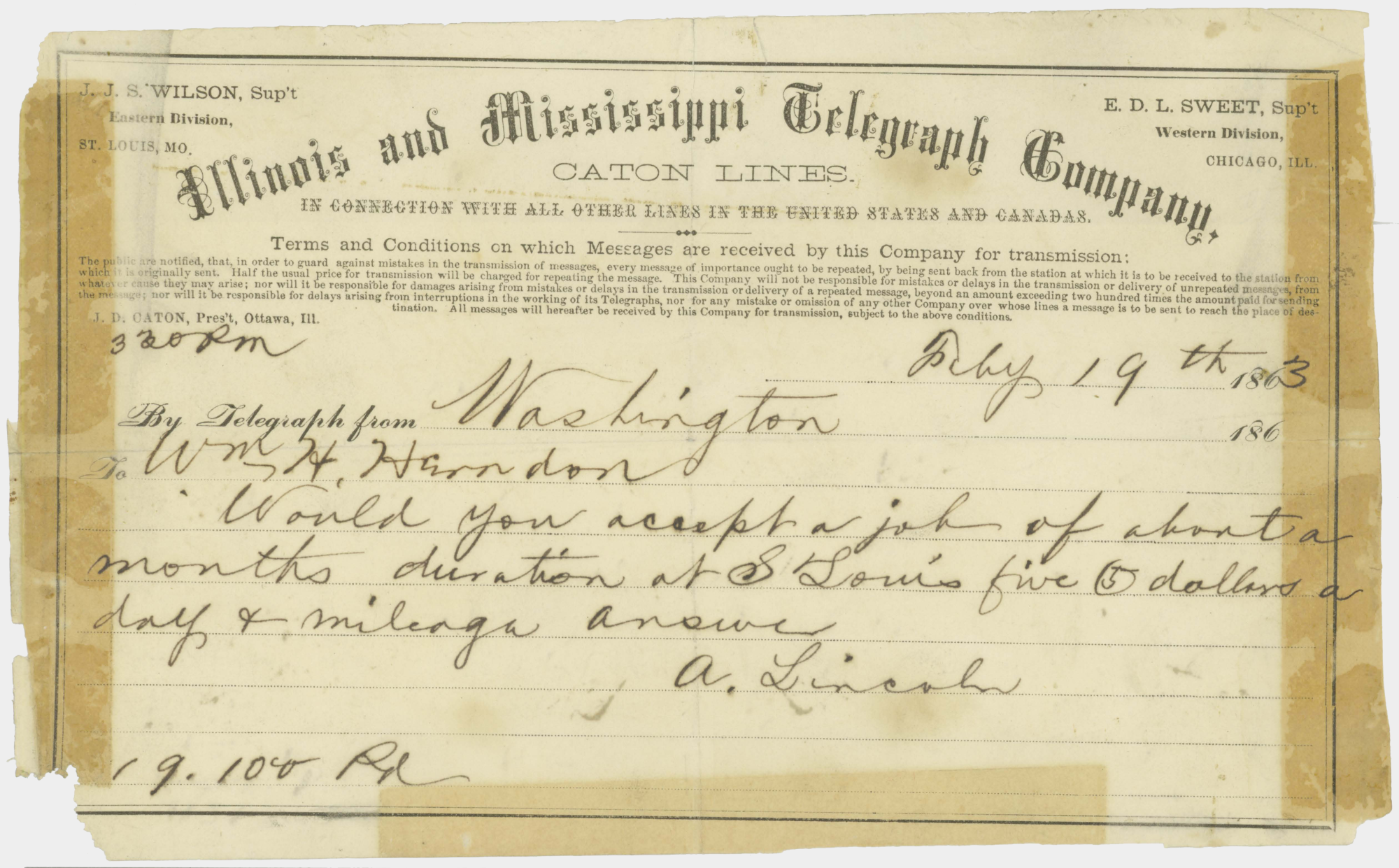

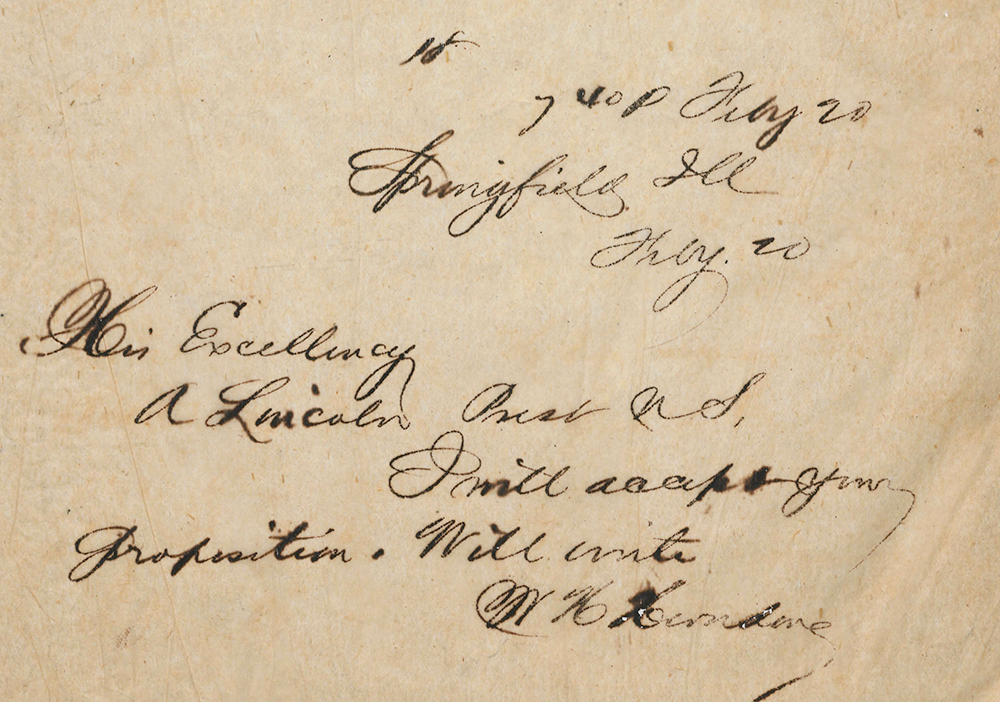

Herndon assured the readers of the Illinois State Journal, “The dispatches between Lincoln and myself will be found in Springfield and Washington City, and I refer to them for the particulars.” In fact, there is corroborating evidence in the National Archives to support much of Herndon’s story. On February 19, 1863, Lincoln telegraphed Herndon: “Would you accept a job of about a month’s duration at St Louis, five dollars a day & milage? Answer.” Herndon replied the next day: “I will accept your proposition. Will write.” Two typescript letters held at the University of Illinois archives and a manuscript letter in the Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress further corroborate Herndon’s account. On February 23, 1863, Herndon explained to John G. Nicolay why he publicly accepted the position but then privately turned it down: “I preferred this course for I wanted no outsiders to say that I would not accept office, etc., from Mr. Lincoln. I cannot consent to accept such appointment; because I do not need it—don’t wish it—can’t leave my own self sustaining business, unless wished—demanded by Mr. Lincoln.”

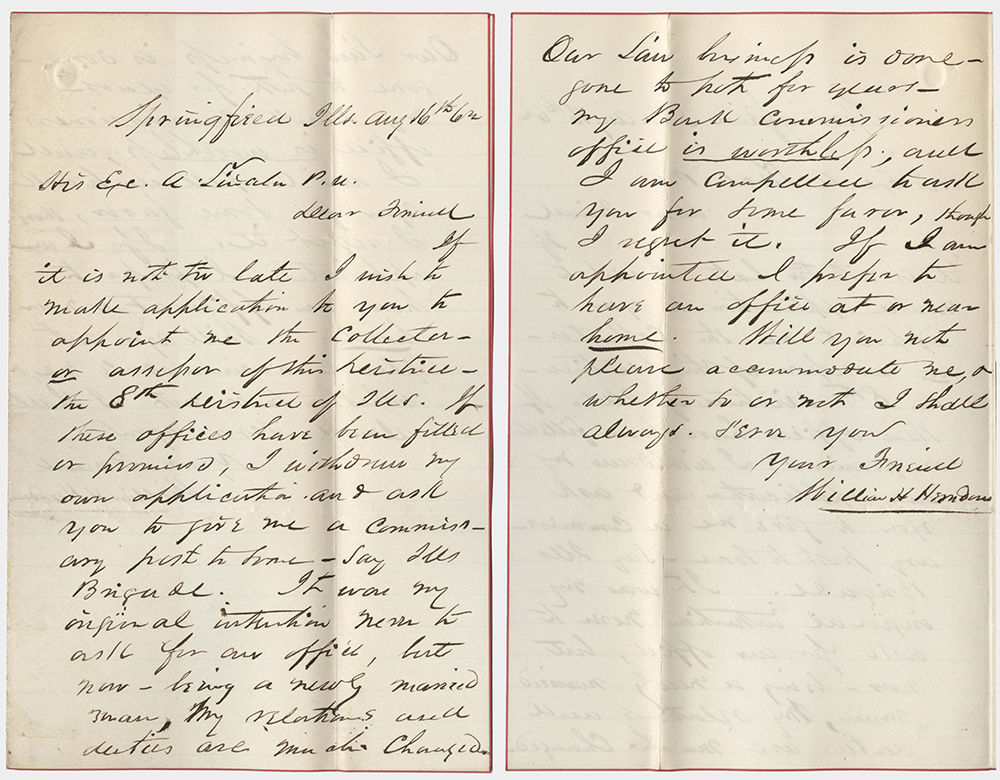

But was this explanation entirely forthright? A previously unpublished letter at the National Archives reveals that Herndon had sought a patronage position for himself a few months earlier and not received it. The letter also sheds light on the state of the Lincoln and Herndon law practice during the Civil War.

Springfield Ills. Aug 16th 62

His Exc: A. Lincoln P[res]. [of the] U.[S.]

Dear Friend

If it is not too late I wish to make application to you to appoint me the Collector—or assessor of this District—the 8th District of Ills. If these offices have been filled or promised, I withdraw my own application and ask you to give me a commissary post to some—say Ills Brigade. It was my original intention never to ask for an office, but now—being a newly married man, My relations and duties are much changed. Our Law business is done—gone to pot for years—My Bank commissioners office is worthless, and I am compelled to ask you for some favor, though I regret it. If I am appointed I prefer to have an office at or near home. Will you not please accommodate me, & whether so or not I shall always serve you

Your Friend

William H Herndon

The docketing on the letter indicates that no action was ever taken on Herndon’s request. Quite likely, Lincoln never saw it.

This letter was discovered on the website of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a documentary editing project run out of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, that seeks to locate, transcribe and make available to the public every document sent to or from Abraham Lincoln. Members of the public are free to search their online collection, which contains high resolution scans (used here as illustrations) of more than 82,000 documents from the National Archives and Library of Congress. Hidden in plain sight—just waiting to be discovered—are gems that can reshape how we understand aspects of Lincoln’s life.

§§

Readers can visit the Papers of Abraham Lincoln website at: papersofabrahamlincoln.org

Their online collection of documents from the National Archives and Library of Congress is available at: papersofabrahamlincoln.xmlref.com