Interview with Ron Keller

An Interview with Ron Keller, Author of Lincoln in the Illinois Legislature.

Sara Gabbard: I know that this book is a product of the Concise Lincoln Library, a series from Southern Illinois University Press. What led you to this specific topic?

Ron Keller: Having served for many years as director of the Lincoln Heritage Museum and teaching at the only institution of higher learning named for Lincoln in his lifetime, Abraham Lincoln has assumed a rather prominent role in my life. My background is American political history, so naturally Abraham Lincoln’s political life has always struck my interest. For the specific topic of Lincoln as Illinois Legislator, I was actually first contacted by Sylvia Rodrigue of Southern Illinois University Press, who asked if I would be interested in writing for their Concise Lincoln Library series. I had mentioned to Sylvia prior to her invitation that I had considered writing on some aspect of Lincoln’s political career, but had thought the topic of Lincoln was nearly exhausted. She relayed that Lincoln as an Illinois state representative had not been the subject singularly of a one-volume book since Senator Paul Simon released his biography in 1965. She convinced me that the topic deserved a re-examination. Despite initially resisting the temptation to add to the mountain of scholarship already published on Lincoln since his death, I decided to do so. Upon re-reading Simon’s biography, it was clear that perhaps a fresh perspective was in order.

SG: When did Abraham Lincoln first decide to run for the Illinois legislature?

RK: Lincoln’s first attempt for the legislature was in 1832, though in that first run he met defeat due to being called away from the campaign trail for several months to serve as a captain in the Black Hawk War. By the time he returned to New Salem, the election was only a month away. Even in his loss, Lincoln felt good enough about his 1832 electoral showing to believe he had a very good chance of winning the next time around. He then ran again in 1834 and was successful. The moment when Lincoln actually decided in his own mind to run for the legislature may have come in 1831, shortly after arriving in New Salem. Despite not knowing many residents when he first stepped foot in the community, he took an immediate and ready interest in politics in his new town, helping out in a local election, and greeting as many local residents as he could. Was he just being friendly, or did he have his eyes on the legislature even then? I think the latter.

SG: Did he seek advice from others? Did he have specific mentors?

RK: Even in his youth, Lincoln was drawn to politicians on the stump, mesmerized by their ability to captivate a crowd with words and wit. As a potential political aspirant himself, Lincoln felt self-conscious about his lack of education and meager upbringing. However, he seemed confident in his abilities and built upon them, and fellow townspeople helped cultivate those skills. For being a frontier town, New Salem surprisingly contained some very educated people. Lincoln sharpened his oratory skills when resident James Rutledge organized the local debate society, and loaned books to Lincoln. Jack Kelso introduced him to enlightenment thinkers, which undoubtedly opened up for Lincoln a new way to think about the world. The village schoolmaster Mentor Graham tutored Lincoln in math, and in reading and writing, all necessary skills to be taken seriously as a politician. Justice of the peace Bowling Green, whose court proceedings intrigued Lincoln, was perhaps the first person to buy into the twenty-two year-old as a serious candidate for office. Lincoln’s most influential mentor in those years was John Stuart from Springfield, whom Lincoln met and befriended during their stint together in the Black Hawk War. It was Stuart who counseled and molded Lincoln to become a successful politician and legislator during the 1834-1835 session when Lincoln became Stuart’s protégé in the Illinois General Assembly.

SG: How important was party affiliation at the time?

RK: In 1832 there was not yet a hardened and organized political party structure in place, but one of the fascinating national developments during Lincoln’s tenure in the legislature was the rapid ascent and solidification of party politics and party allegiance. In just a few short years, really even by 1836, political candidates were expected to identify themselves by party identification: Democrat or Whig. Andrew Jackson in 1832 won a second term to the presidency but his killing of the national bank and other measures expanded his presidential authority to the point that many opponents in Congress called him “King Andrew.” They formulated themselves into a political movement called the Whigs, the same name as the British political party whose members believed more power rested with Parliament. Thus the two-party system was born. Though much of Illinois gravitated to Jackson’s Democrats, Lincoln aligned himself with Kentucky Senator Henry Clay’s Whigs. Party politics became so important that, whereas local political issues took highest priority before 1836, after that, the topics that demanded the attention of legislators were defined by a political party stance on national issues. One of the most important issues which preoccupied much of the legislature’s attention during Lincoln’s terms was the state bank debate—all a result of the killing of the national bank, which had ripple effects on the states, and which drew the line in the sand between Whigs and Democrats.

SG: Please explain the circumstances of each of his elections.

RK: A politician in the 1830s once observed that the key to electoral success lay in the ability to maintain popularity with the voters by whatever means necessary. Perhaps that hasn’t changed. For better or worse, popularity was key, and Lincoln did what he needed to do to win the favor of the voters. In 1834, Lincoln went on a grassroots hand-shaking campaign to secure his victory. He worked hard, going from farm to farm and village to village, in order to hear what was on voters’ minds. However, voters in his hometown of New Salem wanted something in particular from their legislator: county division. They wanted Lincoln to push through a law to separate from Sangamon County and form a new county in their area. Lincoln did eventually achieve that by 1839, but it took several terms, and some of his constituents reminded him during the process that he still had not achieved what they desired. By 1836, he had proven himself, so voters promptly rewarded him for his rising leadership and attention to their requests, such as road petitions and other constituent care. His advocacy for improved transportation and internal improvements won him support in 1836. In that election, he was joined by the other members of the Sangamon delegation who would take the name of the “Long Nine.” The political power they wielded resulted in the removal of the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield, as well as a massive internal improvements project. The laurels Lincoln and his colleagues garnered from that paved the way for his 1838 re-election. However, after 1838 the country experienced the shockwaves of an economic depression, which plunged Illinois with its colossal internal improvements projects into a heart-stopping debt. Lincoln refused to retreat from the projects against the wishes of his constituents, and that worried him about the prospects for his future. Lincoln doubted whether he would win re-election again in 1840, but did so because he had become a state Whig party leader. His less than impressive showing in 1840 may have contributed to his decision not to seek another term.

SG: How would you rate Lincoln’s legislative record? Greatest success? Greatest failure? Please elaborate on the concept of “internal improvements” for the state.

RK: How to rate Lincoln’s record is really a debatable and subjective question depending upon how you look at it. If we judge his record purely on the number of bills and resolutions he sponsored or introduced, there were only about thirty total. The one issue he most ardently championed and shepherded through the legislature—the internal improvements system—left the state swooning in debt for more than a generation. Those examples don’t exactly scream success. However, he exhibited strong enough leadership that his Whig colleagues voted him floor leader for multiple terms, and he would likely have been elected House speaker if his party had been the majority party in the legislature. His greatest legislative success may have been his famous 1837 protest against slavery that he and fellow representative Dan Stone entered into the House Record. I say that it may have been because it is the only legislative act which Lincoln mentions in his autobiographies, so he must have deemed it significant. However, it should be noted that he wrote those autobiographies when he was a candidate for president for the Republican Party, and when slavery was a major issue.

As to internal improvements, one cannot speak on the history of the state, or even America, in the 1830s without acknowledging the importance of internal improvements. The country had begun to embark on a building spree, recognizing that, in order to have a flourishing economy, roads and bridges and canals had to be constructed. Especially in a nation where the majority of the people were engaged in farming, it was necessary to have an avenue to get products to market in the eastern United States and beyond. River transportation was the best prospect at first, even to Lincoln, and the famed Erie Canal in New York provided the prototype. However, by the mid-1830s the railroad boom proved too tempting to resist, even if the costs were “heart-appalling” as Lincoln termed it. States such as Illinois went on a construction frenzy assembling a patchwork of railroads from one city to another crisscrossing the state, and commencing on the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Much of that construction was on the “faith and credit of the state,” meaning that taxpayers more than private industry provided the promised revenue. When the previously mentioned Panic of 1837 hit, it stopped cold many of the projects which had already begun.

SG: Is there a “sameness” in his performance in the legislature, or did certain terms stand out?

RK: Especially by 1836, Lincoln positioned himself prominently above many of his fellow representatives. He took the lead on internal improvements, on capital relocation, and on the bank debate. He was elevated to Whig floor leader. His colleagues observed that Lincoln was a rising political star in the state. To avoid oversentimentality, let’s face it, had Lincoln not become president in 1860, would we have heard about him, and would I have written about him? Probably not. In fact, one of the reasons I undertook this topic was because Lincoln’s legislative career doesn’t get the attention it deserves. That isn’t to say that his career as state representative isn’t worth examining, and there was not a “sameness” in his performance across the board. In particular, the 1836-1837 session—the session of internal improvements and capital removal—is certainly worthy of examination even if one puts Lincoln aside as the central player. The role and the extent to which the Long Nine executed political influence is impressive for anyone interested in the study of political power. It impressed Thomas Ford, future Illinois governor, enough that he devoted great attention to it in his biography of the era—though it should be pointed out he was critical of the Long Nine’s tactics. Those were his peak years as a legislator.

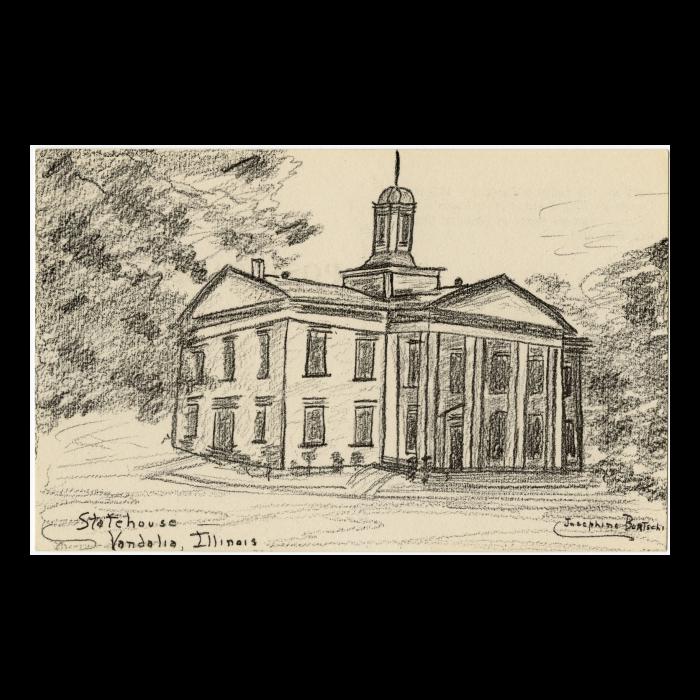

SG: What was Lincoln’s involvement in changing the location of the state capital? Was the move a good decision for (1) his future political career and (2) for the state itself?

RK: Without the crucial role of Abraham Lincoln as “chief of the Long Nine,” as he was termed, it is conceivable that the removal of the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield would not have transpired, or at least not as quickly or in the manner that it did. Lincoln himself directed the Long Nine to curry favor with legislators, to sell the benefits of removal, and to make deals with respect to internal improvements in their respective localities in exchange for capital removal support. He indeed had to court legislators in the southern reaches of the state, who lived closer to Vandalia, and whose constituents feared the diminishment of political power from the southern half of the state. Those familiar with the tactics of the Long Nine confirmed that Lincoln was chief of the tribe. After the session ended, Lincoln was lauded across his county with several communities hosting celebrations to him and to the Long Nine.

Whether the move of the state capital to Springfield was a good move for Lincoln’s political career, the answer is an absolute yes. Lincoln and the Long Nine were Sangamon County residents, and even Lincoln himself was assuredly contemplating in his own mind a personal move of his home from New Salem to Springfield. While serving in the legislature, he was taking the necessary steps to earn a law license. A successful attorney would have little hope of a burgeoning career in New Salem. The opportunities for him with the capital in his hometown were endless. Was the move good for the state itself? Again, the answer would have to be yes. Even those who were opposed to a move of the state’s government to Springfield, recognized the northward shift of the population center. People migrating into Illinois were now settling in central and northern Illinois. Chicago was a growing city and became incorporated during Lincoln’s legislative years. Illinois would have been hampered as a state in which population growth was in the opposite end of the state from its capital.

SG: What was his relationship with other legislators? Were some beneficial in his future political life? Any lifelong foes made during this time?

RK: One of the points that I emphasize in my book is that the connections which Lincoln made in the legislature are with the same individuals who would be present in his story throughout the rest of his life. In many ways, many of these men were very similar to Lincoln: Many were young, had been born in Kentucky, had served in the Black Hawk War, and were eager to rise politically. Lincoln early on learned the necessity of winning friends and confidants. Among those friends, he certainly allied himself more with fellow Whigs, but did not shirk at working across the party line to advance the cause of the state. Many recognized Lincoln’s leadership abilities and enjoyed his company. The names of his early friends and colleagues are familiar to anyone who knows the Lincoln story: Orville Browning, Edward Baker, John Stuart, Ninian Edwards, Robert Baker, Jesse Dubois and others. All are individuals who would remain personally and politically close to Lincoln for the rest of his life. Some of these men campaigned with and for Lincoln for the U.S Senate in 1858 and for the presidency in 1860. Some visited him in the White House.

To be fair, anyone in politics is bound to draw the ire of critics and foes. Lincoln was not immune to that. Democrat Stephen Douglas entered the legislature in 1836 and served only one term. However, it did not take long for Douglas and Lincoln to find themselves on opposite sides of many issues. When John Stuart exited the state legislature to run for Congress, he tapped Lincoln to help stump speak for him against his opponent, Stephen Douglas. Usher Linder, another Democrat, proved to be a great nemesis to Lincoln throughout much of his tenure, and the two often exchanged barbs on the House floor in their speeches. Interestingly, however, Linder became a Whig, and after doing so, Lincoln came to his side, literally, helping protect Linder when he was threatened physically after a speech. Another well-known antagonist in the state legislature was the Democratic state auditor James Shields, who was subjected to ridicule by Lincoln. That relationship nearly landed Lincoln in a duel shortly after departing from the legislature.

SG: What sources proved most valuable in your research?

RK: The Illinois House of Representatives journals from the 1830s and 1840s were invaluable, as they record all of the proceedings, speeches, and votes, and are now available online as a searchable database. They were extremely helpful. The Sangamo Journal and the Illinois State Register were the two primary Sangamon County newspapers of the era and were quite helpful, even with the partisan slant that newspapers often carried back then. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln is always a requisite source. Sources such as Herndon’s Informants, while they carry some obvious bias, were crucial in providing personal accounts from Lincoln’s New Salem contemporaries. Other sources such as the Lincoln Heritage Museum, the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, and the Fayette County Museum provided so much information. Of course, any historian will often look to those who came before, so great past biographies of Lincoln’s legislative years were handy, including that of Benjamin Thomas.

SG: What were the most useful traits which Abraham Lincoln developed in the Illinois Legislature? Were there some lessons which he failed to learn?

RK: One of the most universally appreciated aspects about Abraham Lincoln is his character. We are familiar with those qualities so associated with him, so in researching his career as a state legislator, I indeed set out to determine if Abraham Lincoln exhibited the same character entering his career as he did when president. If so, then it becomes even more necessary to understand those legislative years as perhaps the most formative in his life. I did not come away disappointed. But first to answer what lessons he did not yet appear to learn, in his ambitious pursuit to climb the political ladder and win the support of his party colleagues: Lincoln exercised to a fault the practice of anonymous newspaper assaults against his political opponents. He seemed to take great pleasure in verbally attacking his adversaries, particularly if he saw his own stock rise as a result. While Lincoln often apologized if he realized that his words carried personal insult and hurt, that habit never really ceased until after he departed from the state legislature.

However, history records many more positive traits resulting from his legislative experiences. Most of the accounts from his fellow legislators give praise to Lincoln as an astute learner of policy, as a savvy orator, as a politician gifted in political persuasion, as a staunch and principled proponent of the causes he lent support to, but above all, as a man of his word and the humble servant of the people. His willingness to protest against the institution of slavery in a state which was, at best, apathetic about the fate of slaves showed great courage. His ability to overcome his deep depression after temporarily severing romantic ties with Mary Todd in 1841 demonstrated his perseverance. These are Lincolnesque qualities with which we are all familiar. My contention is, indeed, that the admirable character of Abraham Lincoln was developed not as president, or congressman, or attorney, but years before as a state representative.

Ron Keller teaches at Lincoln College in Lincoln, Illinois.