Lincoln’s Magician: The Saga of Captain Horatio G. “Harry” Cooke

The author wishes to express his deep gratitude and appreciation to professional magicians par excellence, Dean Carnegie and Mark Cannon, for their crucial assistance with this article. They generously provided me with some very important primary sources and much needed materials for this article.

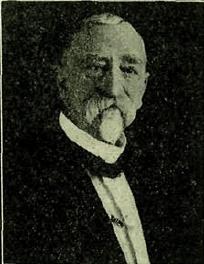

The name Horatio Green “Harry” Cooke is not one usually bandied about when speaking of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. Indeed, you might be hard pressed to find him mentioned in any of the 17,000-and-counting volumes in the great pantheon of Lincoln literature. And yet his saga is a remarkable one and his relationship with Lincoln an untold story of bravery, dedication, prestidigitation and escape artistry. In the end, Cooke would become “Lincoln’s Magician,” a title he wore proudly throughout his long life.

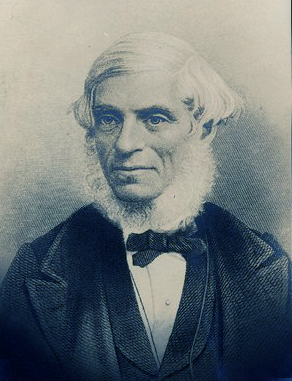

Lincoln was no stranger to magic, having as a youth entertained with rudimentary magic tricks anyone who would watch him. His fascination with magic continued into adulthood as he matured into a successful attorney and politician. Whenever he could slip away Lincoln would frequent magic shows. In fact, he liked magic so much that he returned four times to see the famous American-born conjuror “Wyman the Wizard,’ (whose real name was John Wyman) perform at the Odd Fellows Hall located almost exactly halfway between the Capitol and the White House.

Lincoln also saw the British magician Antonio Van Zandt, whose stage name was “Signor Blitz,” perform several times. Taking a break from the burdens of war, Lincoln and his son Tad watched Blitz perform at a rehearsal for a July 4th parade near the Cottage on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home that Lincoln often used during the summer months to escape the brutal Foggy Bottom heat of the Executive Mansion. While marching, Blitz pulled a bird from the hair of one of the girls on the parade route. This impromptu act stopped everyone in their tracks. So Blitz continued several dazzling slight-of-hand tricks, including whisking an egg from the mouth of ten-year-old Tad Lincoln.

A gentleman from the crowd formally introduced the President to the magician. Lincoln replied, “Why, of course, it’s Signor Blitz, one of the most famous men in America.” So impressed was Lincoln that he invited Blitz to visit the White House. There the magician made a bird appear in Lincoln’s famous stovepipe hat. The bird had a note attached to its wing that read “Victory, General Grant,” referring to the Battle of Vicksburg that Grant would soon win. Awed by this performance, Lincoln reportedly asked Blitz how many children he had made happy in his career. “Thousands and tens of thousands,” Blitz replied. “I fear that I have made thousands and tens of thousands unhappy,” Lincoln morosely responded. “But it is for each of us to do our duty in the world and I am trying to do mine.” What neither knew at the time was that the Union would soon win twin victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg which would turn the tide of the war.

Thus it is not surprising that, when Lincoln learned of young Horatio Cooke’s formidable skills as a magician, the President was determined to meet him if for no other reason than to be entertained. Entertained he was; however, so much more would come from the relationship between the two.

Cooke had been a precocious child, both studious and entertaining. Harry, as his friends knew him, quickly excelled in his studies despite the family moving around several times from Connecticut to Illinois before they landed in Iowa on the eve of the Civil War. Due to his excellent grasp of the English language, as well as his comfort in speaking before groups, the then seventeen-year-old Harry was hired as a teacher for a small rural school and planned on continuing his career in education. But events were about to occur that would forever change Harry’s life.

As the threads of the Union were finally torn asunder and secession drew lines in the sand from which one must decide his loyalties, Harry found himself swept up in the drama. Once he turned eighteen in early 1862, Harry Cooke, now legally an adult, enlisted in the 28th Iowa Volunteer Infantry in nearby Marengo, Iowa, along with his brother, Nathan W. Cooke. Eight of his students followed Private Cooke and his brother into the army as well.

As his diary, letters, and scrapbook attest, Harry Cooke had learned to write in beautiful Spencerian cursive handwriting. This ability, coupled with his expert marksmanship with a rifle, soon caught the attention of his superior officers. “Typewriters were not in general use at this time,” Cooke recalled, “so my skill in penmanship was in great demand.” So, too, was his ability with a rifle as he was quickly named an infantry sharp shooter.

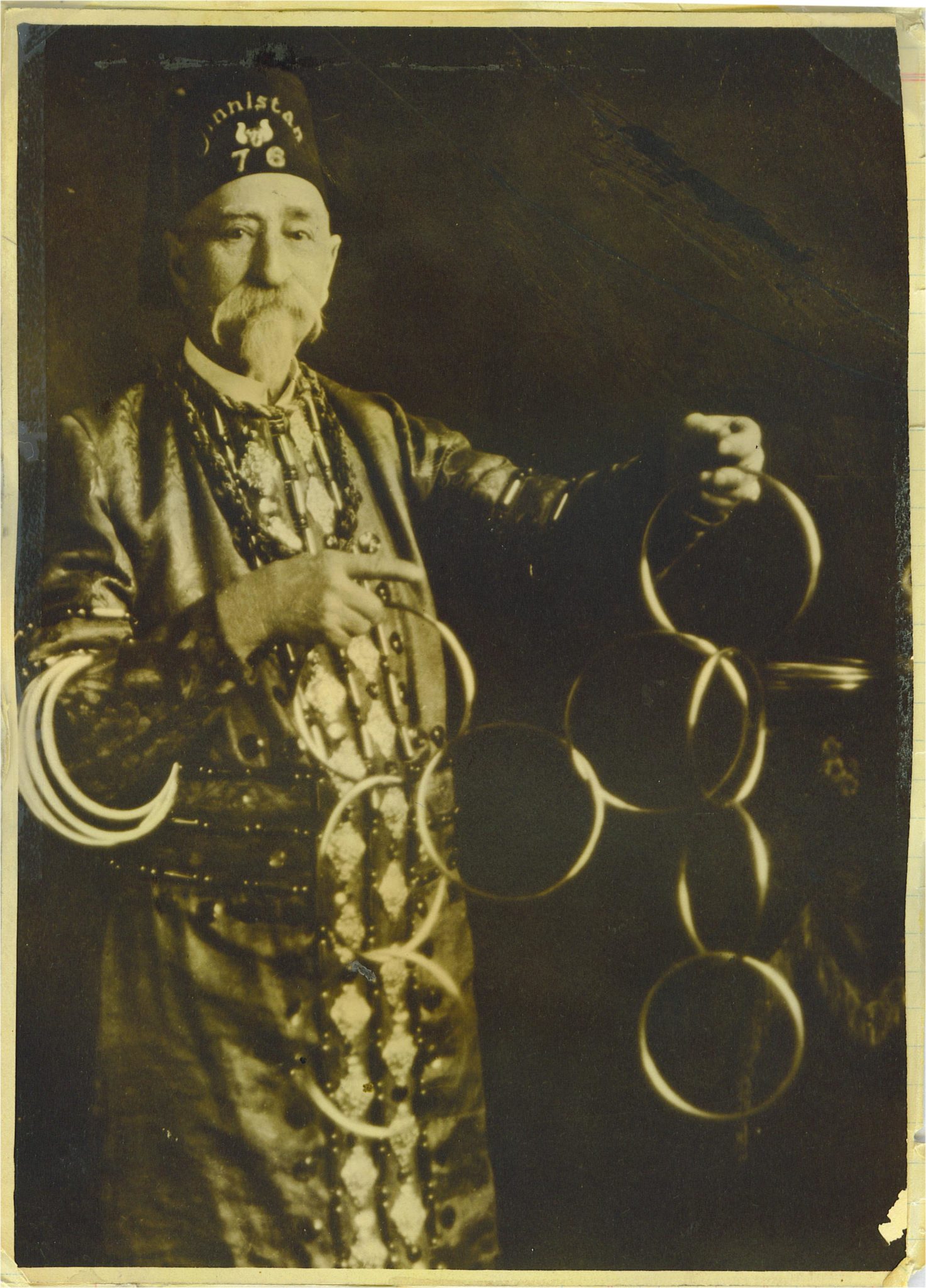

But that certainly didn’t keep Harry out of trouble. Civil War or not, Harry Cooke loved magic and escaping from camp and going AWOL just to see if he could get away with it. “Among my comrades I had the reputation of being clever in performing a number of ‘tricks,’ among which was rope tying feats, the knowledge of which was a strong factor later on in saving my life and [several] of my comrades,” Harry proudly wrote. So it wasn’t long after enlisting that Cooke found himself with his thumbs tied over a limb of a tree as punishment for yet again leaving camp unauthorized. As soon as the solider who had secured him turned his back, Harry performed what would be the first of a lifetime of magic tricks for an audience. “In a flash [I] had freed [my] thumb,” Cooke recounted, “and made a mocking gesture at the back of the retiring officer,” much to the amusement of all who observed. Harry Cooke’s life-long career as an escape artist had begun.

The following spring, Cooke’s Iowa regiment was sent first to Mississippi where he took part in Grant’s siege of Vicksburg and then on to the beginning of the Red River campaign with General Nathaniel P. Banks. Cooke’s job was to perform scouting assignments, skirmishing out ahead of the Union Army as an advance agent or spy.

It was at this time that Cooke, because of his penmanship and knowledge of the English language, was requested to do some correspondence work for General Ulysses Grant. “I first did the private correspondence for Gen. B.M. [Benjamin Mayberry] Prentiss at Helena, Ark.,” Cooke wrote in his diary, “My writing being mostly on official documents, [and it] created a good deal of comment and inquiry as to who was the writer, until I became quite well known at the Executive Headquarters in Washington.” In fact, later Cooke would also write correspondence for Generals Rosecrans, Sherman, and Sheridan

But it was at escaping that young Private Cooke seemed truly to excel. Frequently he would prove to his superior officers that, as hard as they might try to restrain him, he would inevitably shock them by quickly freeing himself. Soon, the youngster began expanding his repertoire. He added a number of magic tricks, studied rope tying, and other skills, and quickly established a reputation as quite the escape artist in his regiment. It wasn’t long before his reputation spread much further than that.

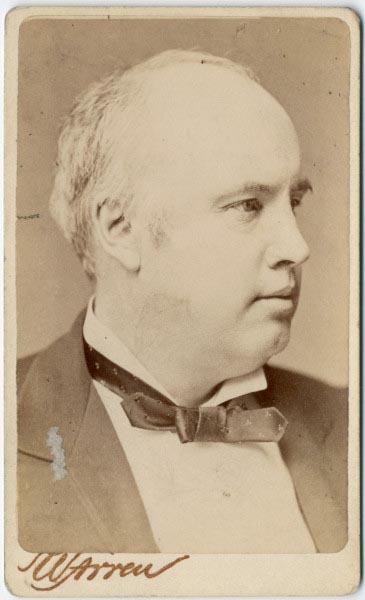

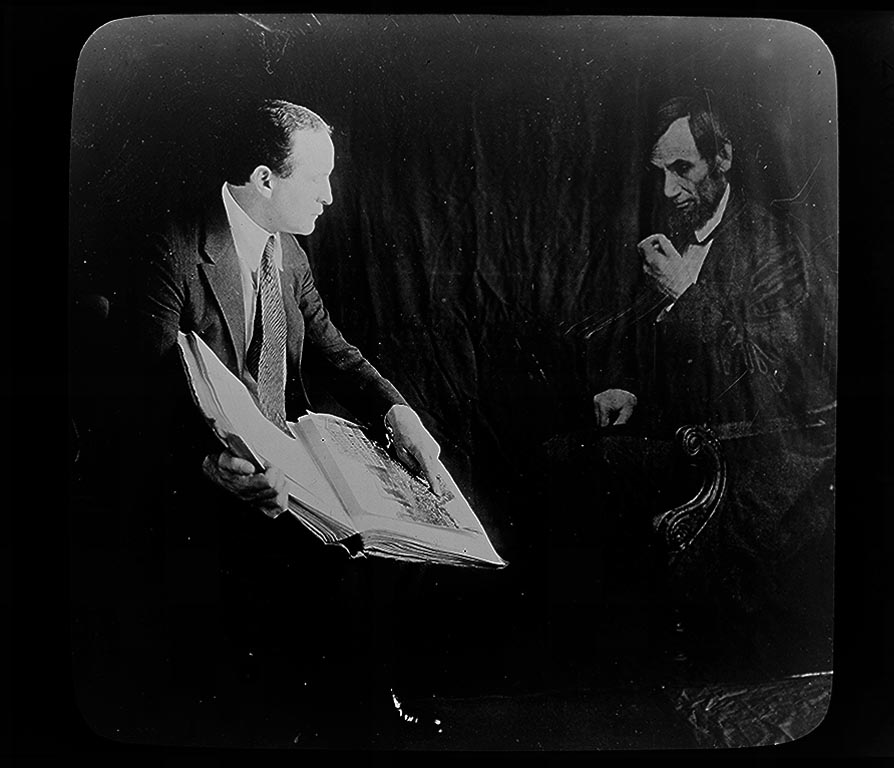

In 1864, Cooke was transferred to the battlefront in the Shenandoah Valley to serve under General Phillip Sheridan. While en route, he was summoned to the office of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in Washington, D.C. When Cooke entered the room, he met Generals William T. Sherman and Winfield S. Hancock, Secretary of War Stanton, the noted attorney and orator Robert Green Ingersoll, Senator Isham Harris of Tennessee, and, much to Cooke’s shock, President Lincoln himself. In Cooke’s diary, the stunned soldier wrote that Lincoln walked over to him, firmly shook his hand, and said, “Well lad, I am informed that you are rather tricky.” Cooke replied that he was not aware that he had been “guilty of doing mean tricks.” The President responded, “Well, I thought we would make an investigation.” They had heard of the young man’s unusual ability to free himself from restraints and were curious to see him demonstrate his abilities.

Cooke was then tied up with fifty feet of rope by two generals and one senator and recounted what happened next in his diary. “When all was ready I asked Lincoln to walk ten feet away. Then I asked Lincoln to walk towards me. While Lincoln was walking the ten feet, I liberated myself and stood up, shaking hands with Lincoln when he was close enough.” The President was both entertained and amazed, as were the others. Cooke continued, “Taking a [$2] ‘greenback’ of the first issue of Federal currency from his pocket, Lincoln gave it to me [and put me] strictly in charge to keep it always, and also told me that he was going to keep an eye on me for something better as I grew older. ‘Here my boy, keep this to remember Uncle Abe by. The Johnnies would have to go some to hold you if you should fall into their hands.’” Cooke later said that “remark seemed rather prophetic, and it was fulfilled afterwards.” Harry kept that $2 bill his entire life.

According to Cooke, at this point Lincoln immediately sat down and personally handwrote a letter appointing him on the spot a Federal Scout whose very dangerous job it was to penetrate the Confederate lines incognito and send back intelligence reports. After the appointment, he was detached from his enlistment with the Army, officially given the brevet-rank of Captain, and designated as “Chief of Lincoln Scouts.” Cooke then handpicked six associate scouts, who affectionately went one better than Lincoln and always referred to him as “Major” Cooke. When he wore his military uniform, over his heart proudly resided a medal which stipulated “Lincoln Scout.” Many of the Lincoln Special Scouts would later go on to become the first United States Secret Servicemen or Pinkerton Agents.

Cooke’s group of scouts accompanied General Sheridan on his Shenandoah campaign in the second week of September 1864. “There was a good deal of skirmishing during the next four weeks,” Cooke recorded, “and my scouting party was kept very busy, but no regular battle was engaged again until the 19th day of October, when at Cedar Creek the enemy surprised our ‘pickets’ before daylight and got inside our ‘lines’ before we were aware of it.”

The Confederate forces had overwhelmed the Federal lines there, compelling them to retreat in great disorder. Cooke was with Sheridan at Winchester when word arrived of the rout. Immediately Sheridan mounted his horse and made his famous ride down the Shenandoah Valley “Hell bent for leather,” as Cooke described, from Winchester to Cedar Creek to stop the retreat and rally the Union forces. Harry Cooke and his six fellow scouts mounted up and started with him, but, according to Cooke, they were unable to keep up with the General’s furious pace. Cooke lamented that he fell behind because his primary purpose as one of Lincoln’s Scouts was to operate out of uniform and spy on the Confederate troops in advance of Sheridan’s Cavalry.

Cooke records in his diary that because they couldn’t keep up with Sheridan, “We were determined to take to the foothills; this was our undoing, for we ran into an ambush of [Confederate] guerillas, 12 of them [from John Singleton Mosby’s famed Rangers].” “Before we could realize our situation,” wrote Cooke, “we were surrounded and there was no alternative; we were in their power and threatened to be shot if we made any resistance.” The great escape artist had become a POW and his skills would soon be put to the test. Unfortunately for Cooke and his men at this time, Mosby was engaged in a savage take-no-prisoners personal war with Union General George Armstrong Custer. In the fall of 1864 word had spread that both generals were executing POWs on the spot.

Thus Cooke had good cause to be worried. In his diary, Cooke writes that Mosby’s men took all of their money, all their possessions, and anything that looked of value; and, they were then forced to change clothes with their captors. “They took all of our letters from our sweethearts,” wrote Cooke, “read them and commented on the contents. They took, also, my most prized possession, President Lincoln’s letter appointing me a scout. I begged them to let me keep it but they only laughed, said I was a healthy looking scout and asked me when I was going to raise some whiskers.”

For the next twenty-four hours Cooke and his fellow soldiers were marched up the Potomac River by Mosby’s Rangers. “One of the gang, about 18,” Cooke remembered, “rode up behind me and began cursing me. I told him he had me at a disadvantage and that he would dare not call me such names if we were on equal footing.” This enraged the Confederate who shouted back at Harry, “D—n you! I’ll show you.” He then raised his gun and aimed at Harry firing three shots. “Fortunately he missed me,” Cooke recounted, “I wanted to taunt him about his poor marksmanship but realized it would probably cost me my life if I did, so I remained silent.”

Eventually they reached a farmhouse where Cooke soon learned that this was the home of the young Confederate who had fired at him earlier in the day. “We were sitting on a wood pile near the gate to the yard when [an] old man came out to look us over,” Harry remembered. “I asked him if he thought he would know us if he saw us again. At that he struck me on the mouth and said ‘I’ll never see you again, the boys will take care of you all right.’ As our lives were in the hands of the bandits I dared not fight back so I had to content myself by telling him that we might meet again someday—and we did.”

Soon after the incident occurred, Cooke and his fellow scouts were taken further up river where they camped for the night. “I learned,” Cooke recalled, “that the guerillas expected to be joined the next day by more Mosby Raiders carrying additional prisoners.” Cooke feared that all of the POWs would then be hanged or shot as spies in retaliation for the execution of Confederate POWs by General Wesley Merritt.

“They tied us to trees and camped in a half circle around us from bank to bank, leaving one of their number in the middle to guard us,” Cooke recorded in his diary. “It was now up to me to get busy figuring out some means of escape. My being tied cut no figure with me, but for the others it was different. The guard was seated with his back against the tree about four feet from me. I had no chance to do anything before midnight and at that hour he roused another man to take his place and went to sleep himself.”

Cooke correctly speculated that the new guard, still groggy from being awakened, was not yet fully aware yet of his surroundings. So he waited patiently and as the guard dozed back to sleep, the escape artist extraordinaire easily freed himself from his bindings and took the guard’s rifle without even awakening him. “It was my plan to get his six shooters also,” said Cooke, “which would give us 19 shots—as the carbine was good for seven—clean up the rest of the guerillas, seize their horses and escape.”

Once he freed his companions, Cooke unsuccessfully tried to convince all of them to escape by way of the Potomac River. But half of them couldn’t swim and they chose to escape by land from Mosby’s Rangers and certain execution. “Nothing remained [for the rest of us] but to swim the Potomac to safety on the Maryland side,” Cooke concluded. They removed all of their clothes, “tied [their] trousers around [their] necks and plunged into the river leaving the rest of our clothing behind.”

Swimming the river proved formidable as the currents were particularly strong. Fatigued from their river journey, Cooke and his men found that they still had the Harpers Ferry Canal to cross. The depth of the water proved fatal for one of Cooke’s severely exhausted men who drowned attempting to navigate the deep canal. The loss of a comrade weighed heavily on Cooke who was now desperate to get back to Union lines.

Down to three men including himself, Cooke led the weary band through the woods which were crawling with guerilla fighters from Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. “White’s Guerillas,” as they were called, concerned Cooke immensely since they were “reputed to be even worse than Mosby’s men, as they generally killed their prisoners as soon as they got them.” Cooke’s harrowing description details the three men’s difficulties. “We wandered in the woods four days with no clothing except our trousers and nothing to eat except birch bark. The fourth day as we were helping ourselves to corn in a field, six armed horsemen rode up and suddenly captured us. We thought they were guerillas as they were dressed in a sort of mixed uniform such as many guerillas wore and they believed us to be guerillas because we were wearing the trousers that Mosby’s men had forced us to put on in place of our own.”

Cooke and his men, however, were informed that they were now the prisoners of a band of Federal Scouts! Shocked by this revelation, Cooke tried to explain that he was appointed Head of the Federal Scouts by the commander-in-chief himself. The leader of the group called Cooke a liar and Cooke said that he really “couldn’t blame him, knowing that he was judging [us] from appearances.” When Cooke asked him who his commanding officer was, he replied it was Major Sage Gallup of the 7th Illinois Cavalry who, as stunning coincidence would have it, happened to be a cousin of Cooke’s whom he hadn’t seen since childhood. At that revelation, Cooke and his men were taken before Major Gallup who confirmed Cooke’s identity, who then, in turn, vouched for his men. They were then given food and new clothing, now twelve days after being initially captured, and they relaxed a bit until they were informed that they had been listed as killed in action. But Cooke spent no time dwelling on that morbid fact; too concerned about his men who had chosen to flee by land, Cooke requested of Major Gallup that they form a search party for them, which they proceeded to do with the help of thirty-three fresh troops provided by the Federal Scouts.

It wasn’t long before Cooke and his colleagues came upon the farmhouse where he was slapped. Now facing a sizeable number of Federal troops in uniform, Cooke included, the farmer claimed he didn’t recognize the soldiers he had abused just a few days before. Cooke interrogated him about his disloyal activities and those of his son in Mosby’s Rangers, but the farmer denied everything. No longer being able to control his anger, Cooke slapped him and later wrote that “I gave him the scare of his life by having him tied to a post and telling him we were going to put some Yankee bullets through him which I really did not intend to do of course. Shooting [you is] too big [for] a coward to be shot like a soldier.” Cooke told him. “But we did give him twenty minutes to remove his most valued possessions and then we burned the house so that it could no longer be a rendezvous for guerillas. Tell your son,” Cooke said, that “when he comes home, what a nice bunch of Yankees we are.”

From there Cooke’s rescue mission took a tragic turn when they sadly discovered his companions who had chosen to escape by land rather than swimming the Potomac River. “We found their bodies hanging from trees,” Cooke lamented, “riddled with bullets and their faces mutilated by birds. We cut them down, buried them and vowed vengeance upon their slayers.”

Setting out on a reign of anger-fueled revenge through the Confederate ranks, Cooke and his fellow scouts vowed to one other that they would never divulge to anyone what transpired on their ride, or the number of casualties that they inflicted. And true to his word, Cooke gave no details in his diary save for the fact that they confiscated many guns, horses, arms, and ammunition, and turned them in to the Quartermaster upon their return.

Returning to Major Gallup’s camp near Staunton, Virginia, weary and emotionally spent by what he had undergone during the previous weeks, Cooke learned in early 1865 that he was to be reassigned as a military clerk in Alexandria, Virginia, a position he readily and enthusiastically accepted. Because Mosby’s Rangers had confiscated Lincoln’s hand-written letter of commission, it was now Cooke’s intention to use his proximity to the White House to see Lincoln and request a new letter from him. Fate, however, intervened and had something else in store for Harry Cooke.

With war’s end in sight, Cooke figured he would be able to see Lincoln with perhaps a bit less difficulty than had the war been raging. He chose what he considered to be an opportune time to visit Lincoln; five days after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. Even if the war was over, Cooke had been heartbroken to have lost the letter written by Lincoln appointing him “Head of the Lincoln Federal Scouts” and he wanted to share with Lincoln stories of his perilous exploits as well as asking to have the letter replaced. On the cool spring evening of April 14, Cooke went to the White House but, as his diary records, was informed that the President had gone to Ford’s Theatre to see the British comedy, “Our American Cousin” starring Laura Keene. Cooke hurried to the theater, purchased his ticket, grabbed a program as he entered, and stood in the back so as not to disturb the audience.

What happened next was sadly described by Cooke in his diary. “About twenty minutes after I entered I heard a pistol shot, at the same moment a man (whom I soon learned was J. Wilkes Booth) jumped from the President’s box to the stage; he fell but got up again, and shouting some Latin phrase, ran through the scenery and out the backstage door. At first the audience seemed to think the incident was part of the play, but someone shouted from the stage, ‘The President has been shot!’ I think it was Miss Keene who cried out. At that, the whole audience rose from their seats; many rushing to the President’s box. Some started after Booth who had mounted a horse in the alley and fled. . . . These events cannot be fully comprehended from reading a bare statement.”

Cooke followed the crowd across the street to the Petersen Boarding House where they took the mortally wounded president. “I remained around the place all night with many others,” Cooke wrote, “and begged that I might be admitted, but that could not be. In the morning [Secretary of War] Stanton came to the door and seeing me, took me into the room where the President lay. He removed the covering from his face, a face that was so physically homely yet so grand and peaceful. But his spirit had passed on to the ‘Great Beyond.’ I did not obtain that for which I sought, for ‘The Master’s Word was lost.’” For the rest of his life Cooke retained the April 14, 1865 Ford’s Theatre program from that fateful night and the $2 bill that Lincoln had given him seemingly so many years ago.

With the close of the war, Cooke returned to his home in Iowa, but his adventures over the previous three years made it seemingly impossible to be content with life in a small rural town. Restless, he moved frequently (Ohio, Illinois, then New York City) before eventually ending up in Los Angeles where he lived the remainder of his life.

Cooke made and invented all the effects used in his very popular magic act. Besides perfecting his magic skills, Cooke, like many people in the late nineteenth century, became fascinated with spiritualism. The glad tidings of spiritualism—that the dearly departed were ever present to offer comfort and advice to the living— were powerfully appealing in the nineteenth century, and the movement’s influence soared with the suffering produced by the Civil War. Spiritualist newspapers proclaimed the faith, and circles of believers established themselves in the leading cities.

Although an extremely clever and gifted magician, Cooke devoted most of his time to exposing fake spiritualism and in fact sold out the Standard Theater in New York for four consecutive months in 1880 doing exactly that. Skeptical of spiritualism from the start, Cooke spent night after night debunking mediums and spiritualists as charlatans long before the man who would become his protégé, Harry Houdini, took up the cause.

For the next quarter of a century or so, Cooke was back on the road with his professional magic and spiritualism debunking show. On May 1, 1924, at the age of eighty, Harry Cooke duplicated his feat of escaping from fifty feet of rope just like he had done for Lincoln some six decades earlier. During this performance, Cooke wore his blue Union Army uniform with the Head of the Lincoln Scouts badge over his heart just as he had done during the Civil War. The result was the same as when President Lincoln observed it; Cooke escaped to the amazement of his audience. It was a poetic and fitting dénouement to an exciting and dangerous life. It would be the last time Cooke wore his uniform. Six weeks later Harry Cooke passed away peacefully in his sleep having been billed as “America’s Oldest Living Magician.”

That title, however, simply seems quite inadequate in describing the amazing, if not historically significant, life of Horatio G. “Harry” Cooke. Perhaps, then, a more fitting title would have been “Lincoln’s Magician.” Certainly, “Uncle Abe”, the Great Emancipator, would have heartily approved.

[Jason Silverman is the Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History Emeritus at Winthrop University.]