An Interview with Lucas E. Morel

An Interview with Lucas E. Morel

An Interview with Lucas E. Morel

by Johnathan W. White

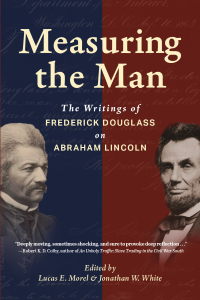

Lucas E. Morel is the John K. Boardman Jr. Professor of Politics and head of the Politics Department at Washington and Lee University. He is the author of Lincoln and the American Founding (2020) and Lincoln’s Sacred Effort: Defining Religion’s Role in American Self-Government (2000); and editor of Lincoln and Liberty: Wisdom for the Ages (2015) and Ralph Ellison and the Raft of Hope: A Political Companion to Invisible Man (2004). He is a former president of the Abraham Lincoln Institute, a founding member of the Academic Freedom Alliance, a consultant for exhibits at the Library of Congress and National Archives, and he currently serves on the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission, which will plan activities to commemorate the founding of the United States of America. His latest book is Measuring the Man: The Writings of Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln (2025), which he co-edited with Jonathan W. White.

Jonathan White: As we approach the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence, how should Americans celebrate this milestone anniversary?

Lucas Morel: Reading the Declaration of Independence would be a good start. My first serious encounter with the Declaration was in a politics class as an undergraduate at Harvey Mudd College. The course was “What is Political Power?” with Professor William B. Allen, a noted scholar of George Washington. Professor Allen asked a basic question to start a discussion of the Declaration. I remembered a social studies teacher in high school who called it a “propaganda sheet.” I kind of understood what that meant, and it sounded sophisticated, so I answered the question by repeating this claim about it being just a propaganda sheet. Professor Allen took a breath and then asked me, “Mr. Morel, did you read Morel, did you read the Declaration of Independence?” While I was taken aback by the simple question, I confessed I had no answer. But more importantly, I understood that Professor Allen was not trying to embarrass me. He was inviting me—and the rest of my peers—to trust our reading of the text as the beginning of a sincere attempt to understand the argument being made by the Second Continental Congress. Rather than replace my ignorance about the Declaration with his wisdom about it, Professor Allen wanted to see if he could motivate me to articulate a serious political argument on its own terms, and not bring to the text preconceived notions about it. That class was the start of my journey into the world of political theory. I proceeded to take every course Professor Allen offered. “The texts are our teachers,” he would say. Again, he wanted his students to begin their study by assuming the author had something worthwhile to say, even something with which they might disagree. In a word, the appropriate posture towards any author was one of intellectual humility.

Given that so much of our study of the American past is consumed by what we think we find wrong with it, the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence deserves our best efforts to try to understand what that generation sought to do on their own terms. This approach does not overlook what we find that was lacking in their efforts, but strives to understand what they achieved in the face of tremendous obstacles.

Given that so much of our study of the American past is consumed by what we think we find wrong with it, the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence deserves our best efforts to try to understand what that generation sought to do on their own terms. This approach does not overlook what we find that was lacking in their efforts, but strives to understand what they achieved in the face of tremendous obstacles.

In addition to reading the Declaration, Americans should read great commentators and activists who looked to the Declaration for inspiration. They could do no better than to begin with the writings of Abraham Lincoln.

JW: What first drew you to the study of Abraham Lincoln?

LM: After transferring to Claremont McKenna College as a junior, I took a course on political rhetoric. My professor, James Nichols (a student of Allan Bloom, author of The Closing of the American Mind), was an expert on Plato’s dialogue, Gorgias, so we read various studies and examples of rhetoric, including the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. I began to see how persuading a single person differed from persuading a crowd—how the logic of an argument was only one part of successful rhetoric, and how speakers need to consider the opinions and prejudices of their audience in order to choose the right methods of argumentation (not to mention the character the speaker brings to the podium even before he or she utters a word).

I saw these three classical aspects of rhetoric—logos, pathos, and ethos as Aristotle presents them—at work in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. I was especially intrigued by the challenge posed by the pathos of America that Lincoln attempted to address. How did he try to steer public opinion towards greater alignment with the principles of equality and individual rights when the sentiments of his audience were shaped by pervasive racial prejudice, even in the free state of Illinois? How did Lincoln try to get white Illinoisans to see the connection between the security of their rights at home and the insecurity of the rights of Black people in the federal territories (i.e., their possible enslavement)? How could the spread of slavery into federal territory lead to its expansion into the free states (hint: he saw the Dred Scott ruling of 1857 as a step in that direction)? How does a politician build a bridge from where citizens are to where he wants them to go? In a government based on the consent of the governed, those who govern can only promote as much justice as they can muster majority sentiment to support. Lincoln’s words remain the gold standard in American politics, perhaps in all politics, for how he attempted to move his fellow citizens in a principled and sympathetic way.

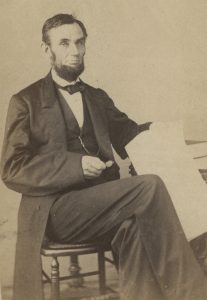

JW: In public lectures I’ve heard you call Lincoln “America’s greatest defender.” What do you mean by that?

LM: Lincoln became the greatest defender of America not only by fighting to preserve the union of American states, but also by fighting to restore the principle of equality as the central idea of America. In doing so, he taught subsequent generations the true principles of self-government.

In preserving the Union, Lincoln preserved a constitutional way of life. He demonstrated that self-government could work from generation to generation. This required not just a commander in chief willing to exercise his authority to put down an insurrection, but a president who could motivate enough loyal citizens to recognize that self-government was at stake and therefore they should be willing to risk life and limb to defend it. Even with his most controversial decisions, like his suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, he directed the American people to the Constitution as the basis of his authority.

He also taught the nation that America was worth defending because America was good. It was the first government in history founded to protect the natural rights of individuals. Its constitution provided the greatest opportunity for the greatest number of people to be free and to pass that way of life down to their posterity—what the preamble to the Constitution calls “the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” Lincoln did not think America was perfect, but he thought the principles of the Declaration and the structures of the Constitution were the best means of an imperfect people to improve their imperfect country—imperfect because it was established under circumstances that made the immediate eradication of slavery too difficult to accomplish while the nation sought its political independence from Great Britain.

As the decades passed, and the political attitude of some Americans towards slavery shifted from treating it as “a necessary evil” to defending it as “a positive good,” Lincoln joined other Americans in reminding the nation of its original promise of equality. He argued that the Founders “meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.” When some Americans insisted on the right to expand racial slavery into federal territory, Lincoln said that the Declaration’s principles should guide their constitutional actions. Viewing those principles as “applicable to all men and all times,” Lincoln had a philanthropic understanding of America as an exceptional nation, and at the moment of the nation’s greatest crisis, he called his country “the last, best hope of earth.”

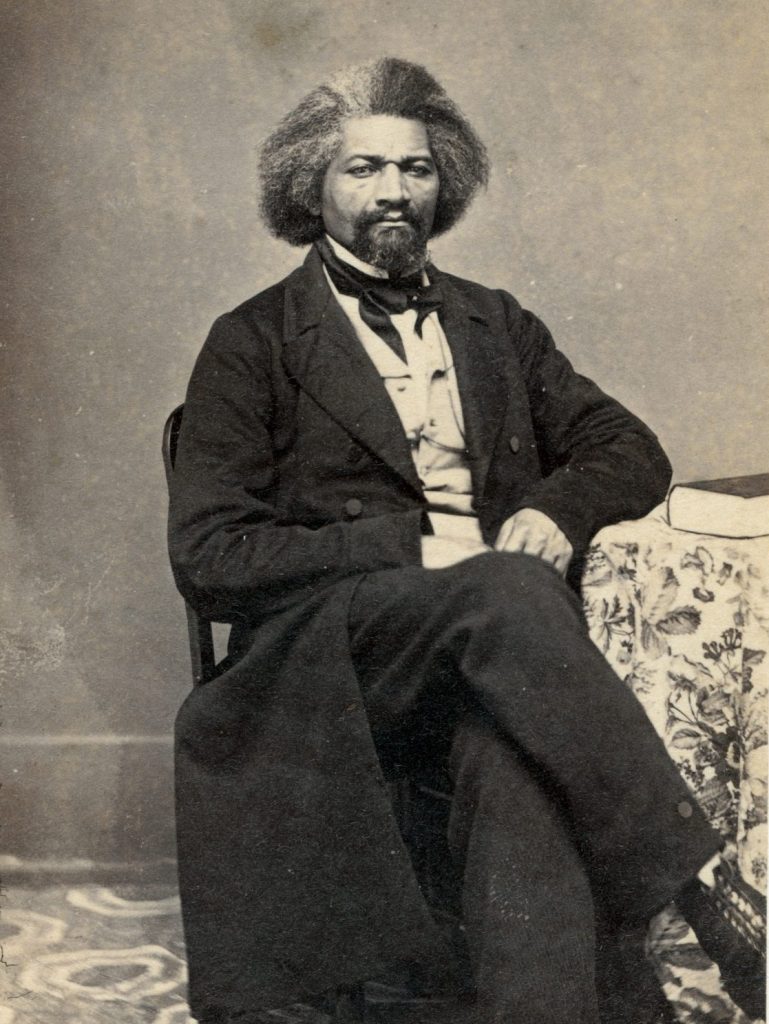

JW: You’ve spent a lot of time thinking and lecturing about Frederick Douglass. What has drawn you to study him?

LM: I study Douglass for the same reason I study Lincoln . . . and Stephen Douglas and John C. Calhoun, not to mention Washington, Jefferson, and The Federalist Papers, as well as more contemporary politicians and activists—both those who have sought to narrow the gap between American political principle and practice and those who misinterpreted or rejected the ideals of the Founding. Douglass once said he sought to get white Americans “to trust the operation of their own principles.” He contributed mightily to the struggle to get Americans to live up to their noblest professions in what one could call the long civil rights movement that constitutes American history.

More specifically, Douglass served as a loyal opposition to Lincoln’s wartime presidency as they jointly sought to bring to fruition the promise of the American founding as expressed in the Declaration of Independence. Douglass’s categorical abolitionism also contrasts with Lincoln’s more prudential antislavery constitutionalism, providing a better understanding of each man’s political thought and objectives. Today, where truly great leaders are few and far between, it’s a tonic to see two of our nation’s best men press the English language and the American regime towards its noblest purposes.

JW: Douglass experienced quite a transformation in his thinking about the United States. Tell us about his shift from being a Garrisonian to an anti-Garrisonian abolitionist.

LM: After Douglass escaped from Maryland, eventually settling in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he began reading an abolition newspaper called The Liberator. It was edited by the most famous abolitionist in America, William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison was a pacifist and a man of firm, albeit idiosyncratic, biblical convictions. He believed that genuine moral reform could only be achieved through moral suasion—namely, the use of words to make moral or spiritual appeals—and not by any use of force, whether violent or political. Rejecting politics as a means of abolishing slavery, Garrison thought emancipation could only be accomplished through organizing abolition societies that would appeal to conscience through speeches, sermons, pamphlets, and books.

In addition, Garrison considered the U.S. Constitution as proslavery because of its compromises with the peculiar institution: the major provisions include the three-fifths clause (which counted three-fifths of a state’s enslaved population towards representation in the House of Representatives), the fugitive slave clause (which required slaves escaping out of a state to be returned), and the non-importation clause (which prevented Congress from banning the importation of slaves into the United States until 1808). Garrison once burned a copy of the Constitution at a Fourth of July rally in Framingham, Massachusetts; described the Constitution as a “covenant with death” and “an agreement with hell”; and called for the dissolution of the American union so free states would no longer have to help slave states to secure their slave population. During the 1840s, Douglass joined Garrison on the stump as an itinerant abolition speaker, recounting the horrors of slavery and lambasting the proslavery character of the Constitution and the American church. He eventually wrote Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845)—the first of three autobiographies—which Garrison endorsed with a lengthy preface.

With the encouragement and financial support of British friends, Douglass decided to publish his own newspaper, The North Star, in December 1847, and began rethinking his interpretation of the Constitution. After studying the writings of Lysander Spooner, William Goodell, and Gerrit Smith (who would become a friend and benefactor), Douglass rejected the traditional proslavery interpretation held by both Garrisonian abolitionists and southern apologists for slavery. Adopting a strict, literal interpretation of the Constitution led him to see “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.”

In 1852, in his “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” speech, Douglass publicly announced that if interpreted “according to its plain reading,” the Constitution was a “glorious liberty document.” For example, neither “slavery, slaveholder, nor slave can anywhere be found” in its preamble nor in any other part of the Constitution. Douglass no longer called for a disunion of the free and slave states, arguing in 1857 that “it is our duty to remain inside this Union, and use all the power to restore to enslaved millions their precious and God-given rights.” Garrison’s cry of “No Union with Slaveholders” (emblazoned on the masthead of The Liberator) would not relieve citizens of the free states of their responsibility to undo the harm they committed by extending slavery’s lease on life through their original constitutional union with the slaveholding states. Douglass was now a political abolitionist: “My position now is one of reform, not of revolution. I would act for the abolition of slavery through the Government—not over its ruins.”

JW: In what ways were Lincoln and Douglass similar and different in their views of the Founding and the Constitution?

LM: Their understanding of the American founding overlapped quite a bit, both in their interpretation of, and devotion to, the Declaration of Independence, especially its Lockean principles of human equality, individual rights, and government by consent of the governed. Douglass called them “saving principles” and Lincoln called its expression of self-government “absolutely and eternally right.” Both men were antislavery men. They agreed that the Founders viewed slavery, in Lincoln’s words, as “an evil not to be extended,” and under the U.S. Constitution, sought “the peaceful extinction of slavery.” As Douglass observed, “All regarded slavery as an expiring and doomed system, destined to speedily disappear from the country.” Both interpreted the Constitution in light of the principles expressed in the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln referred to the Declaration’s equality principle as “an ‘apple of gold’” and the Constitution as “the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it.”

The fundamental difference was their interpretation of the constitutional clauses addressing slavery. Lincoln held the conventional view: despite never using the word “slave” or “slavery,” the three-fifths clause, the fugitive slave clause, and the non-importation clause were all the result of compromises between states that wanted to hold onto the peculiar institution for the foreseeable future, and states that did not want the federal government to bolster slavery’s grip on America. Ultimately, the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia concluded that maintaining national unity required concessions to a minority of the slaveholding states—South Carolina and Georgia in particular.

Without the American union, Lincoln believed there would be no security for liberty. Liberty required political independence from foreign powers; and independence required unity among the American states. To maintain that unity required that compromises be made, especially regarding slavery. Lincoln said, “I think that was the condition in which we found ourselves when we established this government. We had slavery among us, we could not get our Constitution unless we permitted them to remain in slavery, we could not secure the good we did secure if we grasped for more, and having by necessity submitted to that much, it does not destroy the principle that is the charter of our liberties.”

In 1858, Lincoln stated, “I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any Abolitionist,” but Lincoln thought that the federal nature of the U.S. Constitution—the American people dividing political powers between state and federal governments—left slavery mainly as a state institution. Congress was empowered to act on the peculiar institution in only a few cases (as the clauses mentioned above indicate), and could only abolish it within a federal context, like the territories out west. It possessed no authority to abolish it where it already existed in the states.

Douglass interpreted the constitutional clauses that dealt with slavery more strictly than Lincoln. As noted earlier, Douglass’s interpretation of the Constitution through “strict construction” denied “the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it,” an admittedly unconventional reading. Precisely because the so-called slavery clauses never used the word “slavery,” Douglass thought they should not be construed to apply to enslaved people. Moreover, since the preamble explicitly mentioned “justice,” “domestic tranquility,” “general welfare,” and “the blessings of liberty,” Douglass thought the Constitution should be construed according to a plain reading of the text, and not any intentions of its framers, who after all met and deliberated in secret. As Douglass noted, “nothing but the result of their labours should be seen, . . . free from any of the bias shown in the debates.” The debates “were purposely kept out of view, in order that the people should adopt, not the secret motives or unexpressed intentions of any body, but the simple text of the paper itself.” This is what he saw as “the advantage of a written constitution,” intended to last “for ages.”

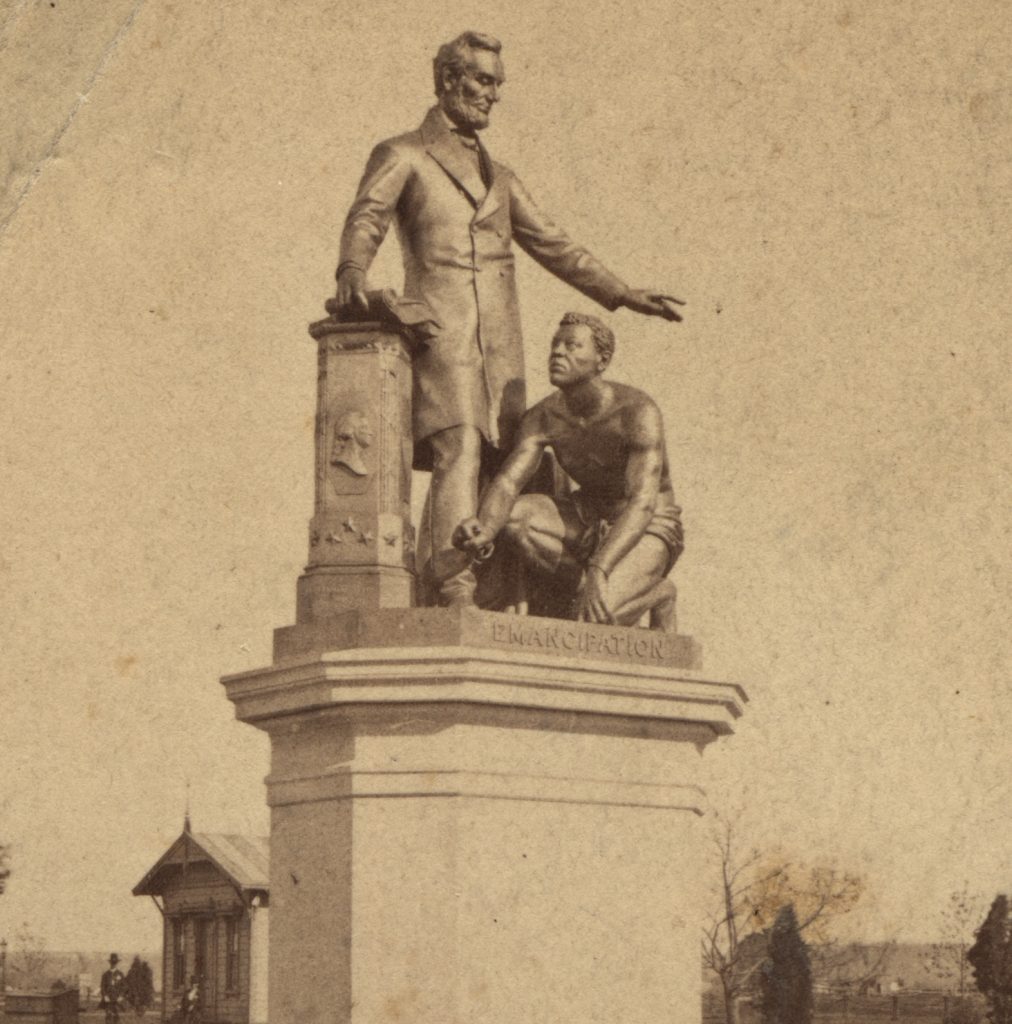

That antislavery Constitution, Douglass believed, permitted Congress to abolish slavery as an existential threat to the American republic. This is what made Douglass a vigorous critic of Lincoln throughout the Civil War, as the president chose not to make the war to save the Union a war to abolish slavery until over a year and a half had passed. Douglass would later give an account of their differences in a speech delivered in 1876 at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Memorial in Washington, D.C. The climax of his candid, and at times provocative, chronicle of Lincoln’s wartime presidency offers the clearest appraisal of Lincoln’s statesmanship in all of Douglass’s writings: “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

For Douglass, part of Lincoln’s genius was that even though he was sympathetic toward white Americans first and foremost, he saw the justice of extending the principles of the regime equally to Black Americans. Moreover, Lincoln brought enough of his countrymen with him to save the Union and secure emancipation. As Douglass put it in June 1865, “the American people, indebted to themselves for themselves, saw in . . . [Lincoln] a full length portrait of themselves. In him they saw their better qualities represented, incarnated, and glorified—and as such, they loved him.” Without that love, and the civic trust necessary to sustain popular government, Lincoln could neither have preserved the Union nor emancipated slaves.

Douglass concluded that Lincoln “knew the American people better than they knew themselves.” He knew what they professed to believe and respected them and their principles enough to hold them to them. Lincoln moved them to a greater commitment to their highest ideals. Douglass acknowledged that while Lincoln’s constitutionalism was not abolitionist in the strictest sense, its antislavery bona fides accomplished what Douglass’s own constitutionalism was unable to do.

JW: Douglass and Lincoln both valued free speech. Why did free speech matter so much to the abolitionists and antislavery politicians in the nineteenth century?

LM: Simply put, political reform required a free exchange of opinions. A month after Lincoln’s 1860 election to the presidency, a meeting of Boston abolitionists was mobbed for daring to discuss how to abolish slavery. Douglass commented on the violence that disrupted that public assembly. “To suppress free speech,” he explained, “is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.” By reminding us of the hearer, Douglass teaches us that free speech seeks an audience. When we forget the audience, the hearer, we forget that free speech is not an end in itself, but a means to an end—the discovery of truth. It is an appeal to reason. Douglass reminded us of the purpose of free speech—why we want to protect it, and why diversity of thought is so important: that is, because the purpose of free speech is to persuade.

Below the Mason-Dixon line, slave states employed despotic measures to silence opposition. “Slavery cannot tolerate free speech,” Douglass observed. Describing a free mind as the “the dread of tyrants,” Douglass said that the right of free speech “is the right which they first of all strike down.” In addition to mobbing abolition speakers, they censored the mails of abolition publications and prohibited slaves from learning to read. Douglass was all the more shocked that the mob preventing “the right of the people to assemble and to express their opinion” arose in Boston, the cradle of the American Revolution.

Douglass once explained why he chose to make his living as an abolition newspaper editor and orator. For enslaved Americans, he wanted “to speak and write in their vindication; and struggle in their ranks for that emancipation which shall yet be achieved by the power of truth and of principle for that oppressed people.” In short, free speech became his vocation, and his words would help shape public opinion in America for the next 50 years.

For him, speech—meaning an appeal to right and not might—held the key to the march of liberty in America. He pointed out that it was slavery that required “violations of free speech” for its protection, but he was confident that “truth must triumph under a system of free discussion.” Douglass declared, “Such is my confidence in the potency of truth, in the power of reason, . . . that had the right of free discussion been preserved during the last thirty years, . . . we should now have no Slavery to breed Rebellion, nor war . . . to drench our land with blood.” He insisted that “slavery would have fallen . . . as it has fallen . . . when men can assail it with the weapons of reason and the facts of experience.”

No one depended more on free speech, the power of words, to rise from poverty to the pinnacle of political power than Lincoln. In his 1858 debates with Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln explained the importance of free speech in a government based on the consent of the governed: “In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently he who moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed.” Lincoln knew by his own political experience that in a free society, those who can shape public opinion are the true rulers. He helped shape the Republican Party into a legitimate opposition party to the Democratic Party in the 1850s. Although he did not win his bid to replace Stephen Douglas in the Senate, two years later he would be inaugurated as the first Republican president of the United States. This required the right of freedom of speech to operate without censorship or interference by the government.

JW: You and I are both very excited to see Measuring the Man: The Writings of Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln in print this fall. What do you hope readers will get out of this book?

JW: You and I are both very excited to see Measuring the Man: The Writings of Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln in print this fall. What do you hope readers will get out of this book?

LM: Regardless of their familiarity with the writings and oratory of Douglass, readers will find this chronicle of his expectations, criticisms, and appreciations of Lincoln from 1858 to 1894 eye-opening in its illustration of the tension between his abolitionist principles and his political strategies. As an abolitionist, Douglass was relentless in his demands that Lincoln turn the war for Union into a war for emancipation and employ Black Americans as soldiers. Readers will gain a deeper understanding of the connection between his calls for abolition and his expectations of equal citizenship in postwar America. For example, even as his political tactics shifted during the Civil War, Douglass was consistent in seeking the vote for Black men as a necessary defense against a slave power he thought would survive the abolition of slavery in the South.

We discovered that British newspapers were printing letters he wrote to abolitionists that no one has seen in 160 years. They display a wide range of his rhetorical eloquence, and the freedom with which he considered alternate paths to freedom and equality for Black Americans. This was especially true at pivotal moments during the Civil War, as Douglass did not always say the same thing to audiences in Great Britain as he did to those in the United States. A war that hastened to a close with the Union preserved but slavery intact was not a war he thought worthy of the blood and treasure of the nation.

Most astonishingly, within days of Lincoln’s assassination, Douglass shared with his British audience the expectation that Andrew Johnson could very well prove a better president for Black Americans than Lincoln had he lived! Douglass believed that Lincoln “thought the rebels should not be punished, but petted, not conquered but conciliated,” and “thought to win back his enemies by his kindness, rather than compel their respect and obedience by his power.” In contrast, he said of Johnson, “As a man he is not equal to Mr. Lincoln, but as a ruler I think he will prove superior” because he “will answer better the stern requirements of the hour.” A summer would pass before Douglass would publicly criticize the new president, followed by a contentious interview with Johnson in February 1866 that dashed any hopes Douglass had for a Presidential Reconstruction that favored ex-slaves over ex-Confederates.

Although the anthology gives only Douglass’s side of the informal debate between him and Lincoln, the reader will infer a general sense of what the president was saying and doing (or failing to do) that disappointed Douglass. I guess you and I will need to get working on a companion volume, “The Republican Responds to the Radical,” to make it more of a fair fight!

JW: Now there’s an idea! Thank you so much for joining us today!