THE SON OF THE GREAT EMANCIPATOR: Robert Todd Lincoln and African Americans

THE SON OF THE GREAT EMANCIPATOR: Robert Todd Lincoln and African Americans

By Jason Emerson

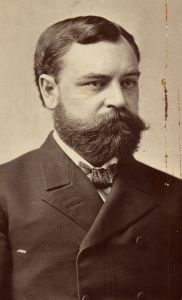

In recent years there has been a renewed output of scholarship analyzing Abraham Lincoln’s interactions with African Americans, but scholars have yet to adequately examine how this aspect of Lincoln’s life may have influenced Robert T. Lincoln, who was nearly 22 years old when his father died. Historians and Lincoln enthusiasts love to hate Robert Lincoln, accusing him of being “cold and haughty,” “aloof,” “aristocratic,” and “all Todd, no Lincoln.” Among these writers, a common accusation is that Robert disliked, disrespected, and disregarded African Americans. Of the two main pieces of evidence cited for this viewpoint, one is almost certainly apocryphal, and one is speculative.

The apocryphal one was written in a 1971 autobiography by Adam Clayton Powell, a civil rights leader and longtime congressman from Harlem. Powell claimed he worked as a bellhop in the Equinox House hotel in Manchester, Vermont, during the summer of 1926. Powell wrote that Robert Lincoln, who “hated Negroes,” would arrive at the Equinox House “every night” for dinner, and “whenever a Negro put his hand on the car door to open it, Mr. Lincoln took his cane and cracked him across the knuckles.” Powell, an African American with extremely light skin color, was supposedly appointed Robert’s personal bellhop because he looked white, a change that “satisfied” the 82-year-old Lincoln.

The speculative proof of Robert Lincoln’s racism was that the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922—a massive event that drew more than 50,000 people—had segregated seating. Not only that, but the keynote address of Robert Moton, president of Tuskegee Institute, was censored as too radical when it was learned that he was going to criticize the federal government for failing to protect the rights of African Americans. The logic in this argument is that Robert Lincoln must have known about the censorship and the segregation and failed to address it or stop it.

While the record of Robert’s interactions with African Americans is relatively slim, it is large enough to deduce a reasonable idea of his feelings towards Black Americans. Like his father, he recognized the common humanity of Blacks and whites, but he was also cognizant of the realities of the age in which he lived. This meant that as a businessman, he sometimes prioritized profits ahead of social justice. He was, in short, a man of his time who sometimes rose above the prejudices of his era and at other times abided by them.

As a child in Springfield, Illinois, Robert Lincoln grew up in a town that had both free and enslaved Black people in the community, although the numbers of both groups were small. As Michael Burlingame shows in The Black Man’s President: Abraham Lincoln, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Equality (2021), the Lincoln family interacted with Black neighbors (Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks), Black hired help (housekeepers Mariah Vance, Jane Pellum, and Ruth Stanton, and odd-job man Henry Brown), and Abraham Lincoln’s close friend and barber, William Fleurville (sometimes spelled Florville), also known as “Billy the Barber.” There were Black men and women throughout the town, and Abraham Lincoln even represented some African Americans through his law practice. Springfield residents who later reminisced about their interactions with the Great Emancipator agreed that he was just and kind to everyone, including Black people—a “racial egalitarian,” as Burlingame characterizes.

Among those who worked in the Lincoln home, Robert had a special fondness for Mariah Vance, a formerly enslaved woman who worked part time for the Lincoln family from 1850 to 1860, helping with the laundry, the cleaning, and the children. Robert knew her from age seven until he left for prep school at age sixteen. Robert demonstrated the depth of his feelings for her when, 37 years later, in 1896, while campaigning for the Republican presidential ticket in Danville, Illinois, he learned that Mariah lived in town. Robert deviated from his political schedule and visited with his old nanny and housekeeper for hours, eating her homemade corn pone and talking about the old days. He reluctantly left her house to give his speech, then immediately returned for more visiting until his train arrived. After that visit, he reportedly sent money to Mariah Vance every month.

As a young child Robert also saw and interacted with Black people outside of Springfield. When the Lincolns traveled to and lived in Washington, D.C., in 1847 for Abraham’s single term in Congress, Robert, age four, would have witnessed slavery close-up—slaves and slave masters everywhere he looked, and even a slave pen just down the street from the boardinghouse where the Lincolns lived. Also in the 1840s, Robert visited his mother’s relatives in Lexington, Kentucky, on multiple occasions, where he saw slavery not only in the town—chained slave coffles on the streets, in the slave pens, up for auction in the public square, and at the public whipping post—but in the Todd home itself, which contained an average of five enslaved people at any time between 1820 and 1850. Mary Lincoln may not have believed African Americans were less than human, as many white southerners did, but she had no problem with slavery, and she certainly was no abolitionist. In fact, in the 1850s, while complaining about the poor quality of the white (mainly Irish) hired help available in Springfield, Mary half-jokingly told a friend, “If Mr. Lincoln dies, his ghost will never find me living outside the borders of a slave state.”

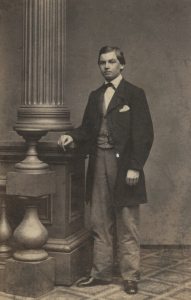

Robert’s years in New England from ages 16 to 21—first at prep school in Phillips Exeter Academy and then at Harvard—also would have greatly influenced his opinions on African Americans. Living in the geographic center of abolitionism, seeing freemen on the streets, listening to learned men castigate slavery, having classmates from rich, abolitionist, New England backgrounds, how could it not? Especially since it is clear that these years greatly affected every aspect of his personality, from the way he dressed, the way he spoke, his habits, his opinions, and his society. One reason his later detractors accused Robert of being “more Todd than Lincoln” was because he had a more genteel sense of manners and refinement, a far cry from his father’s backwoods upbringing.

During the presidential years, Robert was away at college and only present in the White House during school breaks, but his letters show that he talked with his father often, even becoming a confidant to the president. As Robert later stated, “on several occasions my father in his desire to unburden himself to someone in whom he could have entire confidence, gave me brief statements of the conditions of things which were very much bothering him.” On one occasion, however, when President Lincoln shook the hands of two Black army surgeons at a public reception in February 1864, college student Robert Lincoln, prompted by his mother, questioned his father on the propriety of the president being so familiar with Black men. President Lincoln responded, “Why not?” and Robert walked back to his mother.

After the Civil War, the first historical mention of Robert’s association with African Americans came in 1876, when newspapers reported that he and Albert Pullman (brother of railroad magnate George Pullman) financed the college education in London of former slave and Pullman car porter Thomas L. Johnson. Johnson later wrote in his 1909 memoir that the “friendship” of Robert Lincoln and other benefactors “will never be forgotten.”

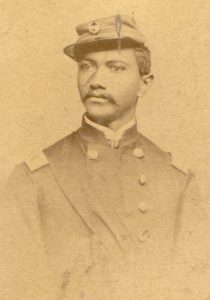

Robert’s primary recorded associations with African Americans came during his tenures as secretary of war (1881–1885) and president of the Pullman Company (1897–1911). In the War Department, Secretary Lincoln confronted the thorny issue of race relations in the army in the form of courts-martial and dismissals of Black soldiers and West Point cadets. In these cases, Robert consistently followed the code of army conduct and military laws, but clearly favored extending rights to Black men when he could.

Not long after assuming his role in President James A. Garfield’s Cabinet, Robert dealt with the court-martial case of Lt. Henry O. Flipper and the expulsion of Johnson Whittaker from the U.S. Military Academy. Flipper, who at that time in 1881 was the only Black officer in the army, was accused of stealing money and was tried on charges of embezzlement and conduct unbecoming an officer. He was found not guilty of the first charge, but guilty of the second, and subsequently dismissed from the service. Secretary Lincoln later said that Flipper’s case was given greater consideration “than if he had been a white man,” precisely because he was the only Black officer in the army, but in the end the record sustained the removal. “All talk of political influence being brought to bear is mere chaff,” Lincoln said.

Whittaker was the only Black cadet in the academy during most of his four years there. In April 1880, he was attacked by classmates, tied to his bed in his underwear, beaten and slashed, and left bleeding on the floor. West Point administrators sided with the men whom Whittaker accused of the attack, and claimed he had staged the whole thing to create sympathy for himself because he was about to fail a philosophy course, which would lead to his expulsion. Whittaker was court-martialed, found guilty, and dismissed from the academy. President Chester A. Arthur eventually overturned the conviction, ruling the court-martial illegal; but the same day, Secretary Lincoln nevertheless discharged Whittaker from the academy—based upon the decision of the West Point Academic Board—for failing the philosophy exam. Lincoln later explained that since assuming office he had been fighting against policies of favoritism at West Point, especially restorations or reappointments of dismissed cadets, and that everyone had learned it was “a waste of time to urge me to overturn the action of the Board.”

In at least one instance Secretary Lincoln intervened to protect the right of a Black man to enlist in the military. In 1884, Gen. William B. Hazen, the commander of the U.S. Signal Service, rejected the enlistment of W. Hallett Greene, the first Black graduate of the City College of New York, because, he claimed, the law did not allow it. When Secretary Lincoln learned of the situation, he not only overturned Hazen’s decision, but rebuked his logic by explaining the various and numerous positions held by African Americans in the army, the government, and even Congress. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper applauded Robert for proving himself to be truly “his father’s son.”

Secretary Lincoln’s handling of the Flipper, Whitaker, and Greene cases shows that as a government official Robert followed his father’s example, treating all men as equals. This was, in fact, a hallmark of Robert’s management style and policy both in the War Department and at the Pullman Company. He was also a delegator. He relied upon the opinions and actions of his supervisory subordinates and upon the written records related to a given case. And this makes sense since he, as the head of these organizations, certainly was not familiar with the details and had no time to do more than read the paperwork.

This was how Robert Lincoln navigated similar issues as president of the Pullman Company. Numerous letters exist from Black and white (although more from white) employees seeking Robert’s intervention in their cases. In every case, he examined the paperwork and relied on the judgments of the immediate supervisors in the field. There were multiple issues regarding African American Pullman employees during Robert’s tenure as president, particularly appeals from dismissed porters, and especially those involved in unionization attempts.

George Pullman began hiring freedmen as soon as the Civil War ended, recognizing a huge and available labor pool, and also believing that ex-slaves, due to their previous roles in servitude, would make excellent car porters. Black porters assisted in the care and comfort of the passengers. They took care of luggage, shined shoes, brushed coats, turned down beds, and looked to any need or request of a Pullman passenger. For former slaves it was a prestigious job that paid more money than they had ever seen and allowed them the opportunity to travel the country. The porters’ friendly, smiling, conscientious service was a hallmark of the Pullman Company, and one that George Pullman often said he could not be successful without.

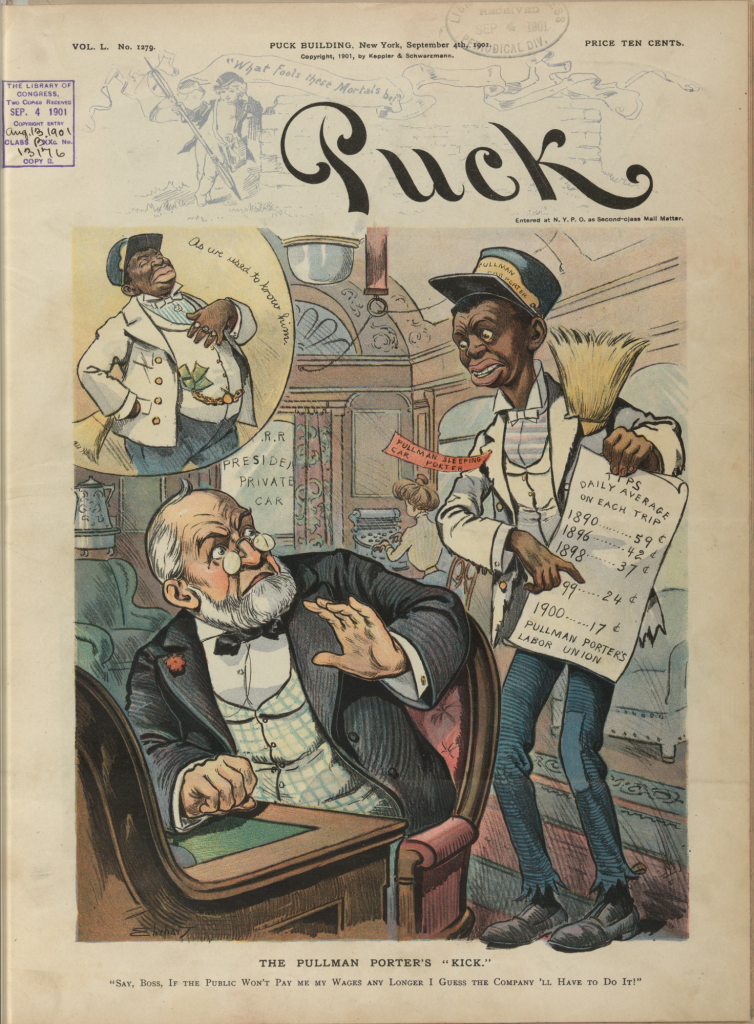

By the end of the nineteenth century, Pullman porters were still all Black, but they no longer were servile ex-slaves, grateful for the chance to work for any amount of payment. They were now the children of former slaves, free Black men who had grown up in a different world: in a more educated and self-reliant Black society, and in a market-based economic environment. This new generation of African Americans saw their labor as a commodity no longer to be taken for granted or given away for a pittance.

Here and there throughout the Pullman Company, porters, after decades of witnessing white railroad workers conduct labor strikes, began to ask for higher wages and fewer hours. Porters were paid small salaries—between $25 and $50 per month by the turn of the century—supplemented with tips from the passengers. Like food service workers who rely on gratuities to make a decent living, porters had to silently endure all sorts of degrading treatment from white passengers in order to receive their tips, a necessity for them to feed their families. Porters also worked shifts of anywhere from twelve to thirty-six hours without a break, and any porter who fell asleep, lagged in his work, or was not fresh and crisp in appearance and demeanor, would find himself dismissed from service for failing to uphold the Pullman standard. The company also required porters to purchase their own work supplies, such as shoeshine equipment, which cut into their monthly pay.

The porters’ plight first received national attention in 1904, after the publication of a 46-page pamphlet titled, Freemen Yet Slaves Under “Abe” Lincoln’s Son, Or Service and Wages of Pullman Porters. The booklet, which circulated around the country, was written by a former Pullman porter who had been dismissed ostensibly for poor performance, but really for attempting to unionize.

The writer, C. F. Anderson, appealed his dismissal to his immediate supervisor, and then to his district supervisor. But when those attempts failed, he wrote directly to company president, Robert T. Lincoln, seeking reemployment. Anderson admitted to Lincoln that he had sent a circular to Pullman porters across the country proposing a national meeting of porter representatives to discuss the best way to achieve increased wages, but insisted he was not attempting any sort of unionization. He stated that his firing was really the result of “malice” on the part of his manager. Lincoln’s secretary, Charles Sweet, responded to the letter, stating that Lincoln had personally reviewed the case and determined that Anderson’s removal for unsatisfactory performance was “justified by the record” and could not be overturned. Anderson was so incensed by the response, and the fact that Lincoln “did not so much as sign his name” to the letter, that he took his grievance public.

Freemen Yet Slaves detailed the wages and working conditions of Pullman porters and contrasted it with the pay and hours of the white Pullman employees (conductors, managers, superintendents). “The Pullman Company regards the six thousand or more porters now in the service as so many slaves to be used in whatever way they can be made to bring the company the most money,” Anderson wrote. The company, he continued, “is enormously rich, and can well afford” to increase wages. The pamphlet reproduced all his letters to Robert Lincoln, in one of which he called out the Pullman president for taking a “blood money” salary of $50,000 a year while failing to improve the lives or redress the grievances of the porters, who would have to work 150 years to accumulate what Lincoln made in one year. “The situation that confronted your father was chattel slavery,” Anderson admonished. “The thing that confronts you now is industrial slavery, which is even worse in some respects than was the former.”

No response by Robert to the pamphlet, either personally or publicly, has been found.

Robert’s actions in this case are difficult to assess without knowledge of him as an administrator. His volumes of existing correspondence show that as head of the Pullman Company, and also as secretary of war in the 1880s, Lincoln replied to every letter seeking a job, a raise, a promotion, a transfer, or a redress from dismissal, whether from a white man or a Black man, in exactly the same way: He reviewed the documentation of each case and relied upon the determinations and recommendations of the immediate supervisor in charge of the applicant. He never, as far as his existing letters show, contradicted or acted against his subordinates’ decisions if he believed they were supported by solid reasoning and documentation.

Robert’s decision not to sign the letter to Anderson was in character. He typically did this when he was too busy to deal with matters he considered mundane or if he felt the letter writer to be particularly offensive, impertinent, ignorant, or otherwise not worth his time. In which category he considered Anderson is unclear. But after making the gibe comparing Robert’s situation and actions to his father—something the son always reviled and found insufferable—Robert, if he even read the pamphlet, certainly never would have given Anderson’s case further consideration.

Freemen Yet Slaves was published not long after another controversy concerning African Americans and the Pullman Company. Beginning in 1900, and reaching a crescendo in 1903, a number of southern states passed Jim Crow laws segregating Pullman cars to prevent Black people from entering cars designated for whites. Black leaders like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois earnestly worked to overturn or prevent such laws from taking effect. Washington wrote multiple letters to Robert Lincoln seeking his support, but Lincoln refused to meet with Black leaders. Robert was an astute businessman who anticipated the likely racist backlash that would ensue if Pullman showed support for Black workers. He knew that boycotts would be bad for business. As the New York Times editorialized at the time: “So long as the compulsion [of desegregation] was exercised, [Pullman would] practically have to give up their service in the Southern States; the whites would abandon it and the negroes would not support it.”

In his business dealings we find a divergence between father and son: Robert put profits ahead of principle, whereas his father, who met with hundreds of African Americans between 1862 and 1865 despite the negative political fallout, put principle first. Indeed, in 1904, Booker T. Washington made a similar point when he blamed Robert for the segregation of sleeping cars. “If he would just stand up straight” and do the right thing regardless of the consequences, “there would be little trouble,” Washington wrote. “George Pullman let the world understand that no discrimination was to be tolerated, consequently there was practically no trouble while he lived.”

The Pullman Company’s troubles with its African American employees did not end there. Eleven years later, in 1915, the issue of pay and working conditions for Pullman porters was not only taken up in newspapers across the country, but also by Congress. The Federal Commission on Industrial Relations held extensive hearings on the subject, and even called as a witness the chairman of the Pullman board of directors, Robert T. Lincoln. Lincoln testified that the tipping system was unfair, that porters’ wages were too low, and that it “annoys me very much indeed,” but that was the way it has always been, as created by George Pullman (who had died in 1897). Robert also defended the system by saying that many porters made more money because of tips than they would if their wages were increased. To increase wages would necessitate an increase in ticket prices, and so, either way, the public would pay the price, whether through tips or higher fees. Still, Robert defended the company. “The one large element that has done more to uplift the negro is the service in the Pullman Company,” he said. But he also admitted that the system was a financial gain for the Pullman Company, which saved $2 million or so a year on the low wages.

Some newspapers lauded Lincoln’s testimony as the first time such honest answers were ever given by the head of a major company. Other newspapers criticized Robert for having views that were “so much different than that of his illustrious father’s.” One newspaper reported that a commission member even asked Robert how his father would feel about the pseudo-slavery condition of Pullman porters. Robert showed his disdain for the question by ignoring it.

Interestingly, despite Robert’s public statements, the Pullman Company increased the annual wages of porters in 1916, although the racial friction did not end and ultimately led to the creation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union.

In the six decades between the end of the Civil War and his death in 1926, Robert Lincoln only appeared in public to honor his father a handful of times. In 1882—the first time he participated in such an event—he joined the Black residents of Washington, D.C., to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the D.C. Emancipation Act, which had been signed by his father on April 16, 1862. Robert accepted the invitation of W. Calvin Chase, an African American lawyer and newspaper editor, and sat on the stage with Chase and other Black city leaders throughout the event. The fact that he attended this anniversary has tremendous import: it shows that Robert revered his father’s legacy as the man who freed the slaves.

In 1916, Robert made headlines when he donated one of his father’s Bibles to Fisk University, a Black college founded in Nashville to educate former slaves. The Bible had been given to Abraham Lincoln, “the Friend of Universal Freedom,” in 1864 by a group of African Americans from Baltimore. Robert Lincoln told the president of Fisk University, “It has seemed to me better that this notable testimonial should be preserved in some institute where its resting place will be permanent, and I can think of no more fitting selection than [this] institution.”

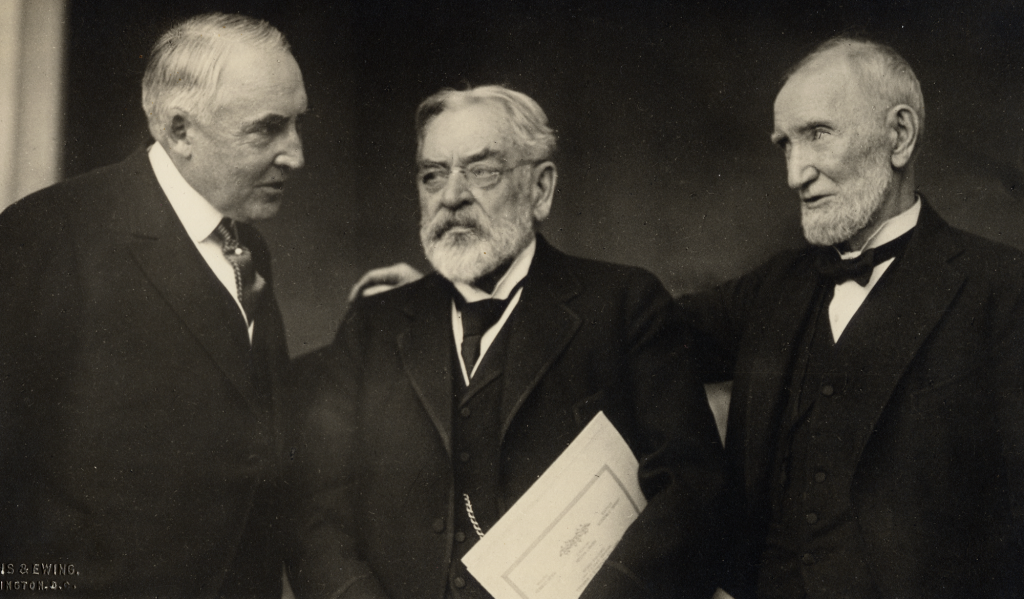

One of the last incidents relating to Robert Lincoln and African Americans concerns the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922. It was Robert’s last public appearance. Photographs show him in awe and pure joy at seeing the great monument to his father. Over the past century, the Memorial has become a powerful symbol for African American rights, including as the site of the concert of the Black singer Marian Anderson who had been refused entrance to the Daughters of the American Revolution’s Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., in 1939; and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech given on the steps in 1963. So did Robert Lincoln condone the segregation of the audience that day in 1922 or have a hand in censoring President Moton’s keynote address? The existing evidence is not enough to allow a conclusion. Robert made clear from the moment he was invited to attend the event that he wanted no part in it other than his presence. He did not participate in any planning, management, or decision-making for the dedication day.

As for the accusation by Adam Clayton Powell that Robert Lincoln “hated Negroes,” it is impossible to confirm. But it is useful to consider how Powell’s personal feelings and politics may have influenced such a story. As a civil rights leader and politician, he fought against the Pullman Company and its anti-union policies for decades. But Powell’s recollection seems unlikely for another reason. During the last few months of Robert Lincoln’s life during the summer of 1926, when he and Powell could have actually crossed paths at the Equinox, Robert’s wife and doctor kept careful watch over his every move. Family records indicate that he did not go to the Equinox “every night” for dinner, as Powell claimed; he ate his dinners at home. It is possible—perhaps likely—that Powell created a story about Abraham Lincoln’s son forty-five years after Robert’s death, when nobody could refute it because nobody else still living had been there.

In the end, Robert Lincoln was not his father, nor did he want to be, no matter how much he admired him. Perhaps Robert did not want the attention; he resented being characterized solely by his surname. Perhaps he did not want any actions he took to become addendums to his father’s historic achievements; he often stated that he did not want anything he said or did to impinge upon his father’s legacy. Nevertheless, the record shows that Robert generally treated Black people the same as whites during his tenures leading the War Department and the Pullman Company. His refusal to desegregate Pullman cars is certainly a stain on his reputation, but all things must be understood within their context; Robert was a businessman, not a politician, and his duty was to Pullman shareholders, not to a voting constituency. Whether Abraham Lincoln would have acted as Robert did is an open question, but he did not free the slaves immediately upon taking office either, despite massive pressure from abolitionists and African American leaders, because he knew the public would not go along with it. Perhaps in this way Robert was more like his father than it seems at first blush, perhaps not. But the overarching truth is that Robert Lincoln learned many lessons from his father, one of which was to see the humanity in all people, to treat them with fairness and kindness, and not to prejudge them based on their membership in a defined group.

Jason Emerson is an independent historian who is the author or editor of seven books about Abraham Lincoln and his family, including Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln (2012), The Madness of Mary Lincoln (2007), and Lincoln the Inventor (2009). He is currently compiling a new edition of Mary Lincoln’s letters and asks anyone who owns or knows of unpublished Mary Lincoln letters to contact him at [email protected].