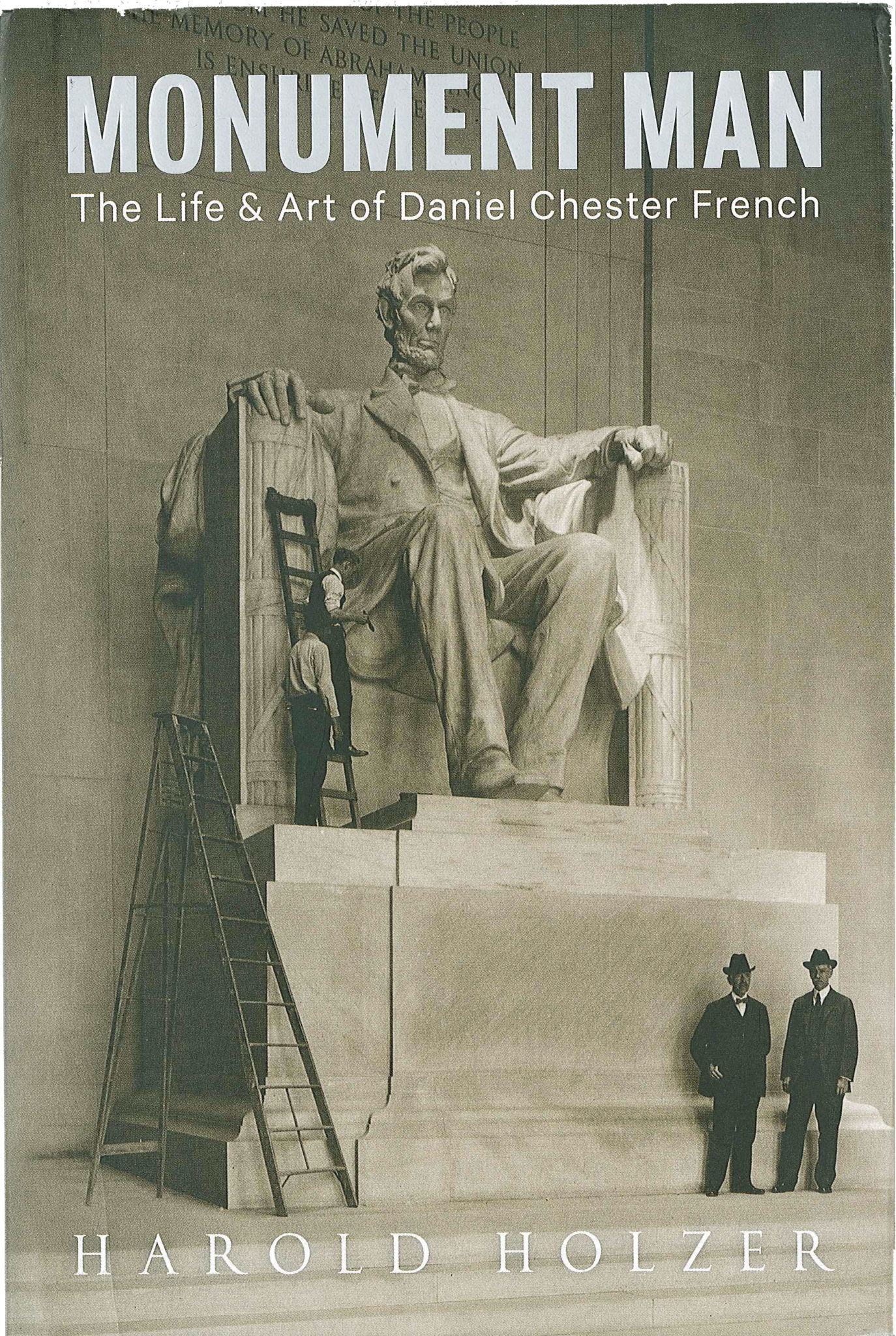

An Interview with Harold Holzer on “Monument Man”

An Interview with Harold Holzer regarding his new book, Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French

[“As one of the foremost living authorities on Abraham Lincoln, Harold Holzer has long straddled the crossroads of history and art with his own inimitable brand of scholarship. Not surprisingly, in this grandly illustrated and beautifully written biography, he proves to be the ideal guide to the life of Daniel Chester French, who transmuted Abraham Lincoln and other historical figures into monumental sculptures of surpassing beauty, poetry, and inspiration. This book will surely rank as the authoritative life of a man whose creations in stone and bronze have become inseparable parts of our historical memory.” Ron Chernow]

Sara Gabbard: While I have read most of your books, I wasn’t sure about undertaking Monument Man because the topic is so vast, and I am woefully uninformed on it. Deciding to “soldier on” after reading Ron Chernow’s description of the book, I am delighted to know more about this remarkable man. When did you first realize that this story should be told? How did you begin such a massive undertaking?

Harold Holzer: I wish I could say I thought of the project myself, but book inspiration comes in so many different ways, often from others. In this case, my friends at Chesterwood, French’s home and studio in Stockbridge, MA, came to me and commissioned the book. So it was written under the aegis of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which owns the French property in the Berkshires, but left completely to me in terms of research and interpretation.

I began at the literal beginning—at the Chapin Library at nearby Williams College, repository of French’s original papers, to read the bird-watching diary the future artist kept as a teenager—which included an entry on the day Lincoln died (alas, without mentioning the assassination at all). Concurrently I turned on the visual experience—the remarkably vivid plaster models in the Chesterwood collection, the heroic statues in Washington, Boston, and New York, and the house and studio themselves. I was reminded again why Mr. and Mrs. French loved the Stockbridge place—it is a truly magnificent setting, a pedestal waiting for a monument as they once described Capitol Hill—in French’s case, as it turned out, many monuments. During one research spree we even got to reside in the “Meadowlark,” the onetime second studio French built across the road for more privacy and more outdoor light.

SG: Please describe Chesterwood.

HH: In its present state—a national trust site open to the public in the warm months—it is a beautifully restored home, artist’s studio, barn gallery and gardens—looking very much as if DCF is still in residence. The great architect Henry Bacon—who later created the Lincoln Memorial—designed both the house and studio building, and there is a stately harmony between the two nearby structures. The home lets in summer breezes and combines luxury with a rustic bow to the environment—beautiful views everywhere, functionality together with striking design touches, much of it collected and installed by French, who loved to haunt local flea markets. The studio is designed not only as a workshop but a showplace—a site where French could not only roll up his sleeves (figuratively, of course—he was quite formal even with his hands in a vat of clay) and work but also entertain and impress potential clients and patrons; it’s filled not only with eclectic furniture and décor from his Concord days and from abroad, it not only includes a teeming workroom still filled with the tools of the trade; it is connected to a lovely porch where I can just imagine this canny artist-entrepreneur wining, dining, wooing, and impressing his visitors. Just spectacular and well worth a visit. The docents, by the way, are extraordinarily welcoming and well-informed. And so many of French’s plaster models are on display it’s a rare encounter with creativity.

SG: What was French’s relationship with the following:

HH:

The Alcott family: Of course as a resident of Concord, Massachusetts, Dan knew all the Alcotts well: they were local royalty. May (the model for “Amy” in Little Women) was Dan’s first art teacher; the young man’s father turned to her and asked if she might frankly assess the boy’s talent—so he’d know whether to encourage Dan to pursue sculpture as a career. May endorsed the idea and Dan was liberated from MIT to devote his life to art. In gratitude, he carried with him for the rest of his life, wherever he might be working (Florence, Paris, New York, the Berkshires) the crude sculpting tool May had once given him—his first. Later, May’s famous sister Louisa May Alcott demanded a VIP seat at the dedication of Dan’s 1875 Minute Man in Concord—and stormed off in a huff when no space could be found for her. And finally, when Dan returned to his hometown after studies abroad, he produced a fine bust of old Bronson Alcott. So he was very much involved with the entire Alcott clan for sure.

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Emerson was an early DCF champion—helping him secure his first major commission, for the Minute Man, without subjecting him to a formal competition—openly favoring and encouraging the hometown boy even when his first proposed design failed to win approval. Of course Dan wasn’t offered a fee for it, just expenses, so he more than repaid their confidence by producing an icon. Emerson of course appeared at its 1875 dedication—so the families remained close. Later, when DCF finished an unrewarding post-Florence stint as a government-paid (per diem!) sculptor in Washington, he returned to Concord and decided to sculpt Emerson from life. The result was one of his greatest achievements, and one of the best portrait busts ever created in the 19th century. DCF later produced a larger seated statue for the Concord Library. So their associations ran deep.

Theodore Roosevelt: TR bared his famous teeth at DCF one day at the White House—and both Mr. and Mrs. French were smitten. TR wanted French to help him organize a fine arts commission that could take hold of developing the Washington Mall and other public spaces in the capital. French would later serve as its chair when Taft became President. Unfortunately, DCF never sculpted that great face of Roosevelt’s—a loss to art and history alike. But French was loyal enough to remain a TR supporter even when his fellow Trustees at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—like J. P. Morgan—denounced him.

SG: What were the various sites which you and Edith visited during your research for this book?

HH: We saw the replica of French’s Republic in Chicago (it once rivalled the Statue of Liberty as a national emblem, but the original was not built to last; now the Obama Library is being built near the replica. We revisited the Lincoln Memorial many times, checked out the Boston statues (like Joe Hooker and the Millmore Memorial), then had a wonderful two days in Concord looking at early works like the Emerson statuary and the memorial to the Civil War Melvin brothers in the local cemetery: Mourning Victory, a masterpiece. We regret that we haven’t—yet—made it to Lincoln, Nebraska (though a fine replica stands at Chesterwood). We had one of our best outings checking out the works closest to home—the New York City statuary from the Bronx (at the Hall of Fame) to Columbia (Alma Mater) to the Hunt Memorial opposite the Frick Museum, to the massive Custom House Continents on the southern tip of Manhattan—not to mention the works across the bridge in Brooklyn. I trusted my memory about John Harvard in the Harvard Yard since out older daughter went to school there and we encountered him many, many times. Happily, the collections at my own professional alma mater—the Metropolitan Museum—boast wonderful bronze models, and marble versions of his works, plus his last great statue, Memory—along with an obscure gem, a plaque dedicated to the Met’s onetime curator of arms and armor, who advised French on his Washington Irving memorial (which of course we visited in Westchester).

SG: Please describe the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial on Memorial Day (May 30) in 1922.

HH: It was one of the most anomalous, indefensible public ceremonies in American history—worse in a way than the sometimes overtly racist dedications of many Confederate Memorials, because this great work was, after all, dedicated to the savior of the Union and the author of the Emancipation Proclamation. The 1922 Lincoln Memorial dedication was not only segregated, but roughly so: African Americans were rousted out of the seats they had held from early morning and forced by mounted police to backless benches at the rear of the crowd. Some understandably left rather than endure the insult. The African-American Press condemned what happened, even if the mainstream press did not. And those who endured the insults and remained on the scene did not even know that the day’s only speaker of color, Robert Russa Moton of the Tuskegee Institute, had to deliver a truncated speech. His remarks were censored by the Harding Administration because they included a paragraph warning that the Memorial would be a “hollow mockery” if Lincoln’s unfinished work on race remained incomplete. To think that aged Confederate veterans—wearing the old uniforms they had once worn to fight to destroy the Union and preserve slavery—got places of honor while the first African-American Rhodes scholar was forced from his seat! It was not America’s finest moment of enshrining Lincoln memory. Fortunately, if belatedly, when the great opera singer Marian Anderson concertized there 17 years later on Easter Sunday 1939 (after being barred from the DAR hall), the trajectory of the Lincoln Memorial turned 180-degrees—and what had been a magnificent statue dedicated at a miserable ceremony became the talismanic icon for American aspiration. Indeed, for the last four score years it has been the symbolic backdrop for heroes striving to finish Lincoln’s unfinished work, just as Moton had hoped. Dr. King and countless American presidents followed Anderson here, and launched new movements for change in its symbolic shadow.

SG: What were the circumstances surrounding George Washington’s statue in Paris?

HH: For one thing it was the first major work French undertook in his brand-new studio at Chesterwood. The stucco walls were still drying when he got a strapping young local boy to pose. Also his first major work overseas. The equestrian was meant to show Washington at the moment he assumed command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts on July 3, 1775—and French provided the requisite drama by showing the general holding his sword high. Dan was on hand on July 3, 1900 for the dedication in Paris. John Philip Sousa, no less, performed the French and American national anthems—so it was a very big deal indeed, as were many statue dedications at the time. Two interesting tidbits: the commission came from the Daughters of the American Revolution, the same organization that would later prevent the African-American star Marian Anderson from singing at its Washington hall—thus “forcing” her to sing at the Lincoln Memorial, forever transforming its iconic status. Second, French may have sculpted General Washington for this great work, but not his horse. By then, French assigned all the “horse work” to a collaborator named Edward Clark Potter. One of the key things to remember about DCF as an artistic genius is that he knew what he was good at and where he was weaker. He felt he didn’t do animals as well or enthusiastically as others, so he farmed that work out. He did the riders—and some magnificent ones, including Ulysses S. Grant.

SG: How many French works of art are displayed in the United States?

HH: Not counting works in Museums (of which there are dozens and dozens), we counted 82 public, outdoor works by French from coast to coast (including your institution’s home state, Indiana—the Ball Memorial in Muncie), along with two in France. French is literally really all over the map, a major presence on the American landscape.

SG: Other than the Lincoln Memorial, which statues did you find: most artistic? most touching? most unexpected? most “eloquent” in the stories they told?

HH: For artistry I’d emphasize Mourning Victory, for one—with its winged angel bowed in mourning for the Melvin brothers who died during the Civil War. For emotion I’d cite Death Stays the Hand of the Sculptor in Boston’s Evergreen Cemetery—a daring and deeply touching tribute to one of French’s rivals, Martin Milmore, who died young. French took a huge risk in combining portraiture with symbolism, showing the angel of death literally seizing Milmore’s mallet as he works on a sculpture of the Sphinx. Somehow he pulled it all off and created a masterpiece. Among the surprises is the Washington Irving memorial that shows the author in front of relief portraits of two of his famous fictional characters, Boabdil and Rip Van Winkle; and also French’s final great work, Memory, a nude woman splayed before the viewer, checking herself out with a mirror!—pretty daring then, and now. And among the most eloquent is the Gallaudet Memorial in Washington, showing the great educator of the hearing-impaired giving hope to a youngster. Remember, you asked me to omit Lincoln—but the standing figure in Nebraska and the enthroned colossus in New York offer all of the above—artistry, emotion, and eloquence that speaks to us as powerfully today as when these works of art were unveiled.

SG: Who made the decision to build the Lincoln Memorial? How was it funded? How long did construction take?

HH: In a way, the decision was made in 1865, right after Lincoln died. But it just took 50 years for Congress to get its act together; yes, there was dysfunctionality then, too. Finally, President Taft turned to the new National Commission on Fine Arts (which French chaired until he sensed the potential conflict, won the commission for the statue, and finally quit!) and organized a new Lincoln Memorial Commission. Congress finally appropriated the money, $75,000 to start, and work began on the building around 1911. The statue actually got installed in 1920, but for some reason the formal dedication was delayed almost two years; some blamed our focus on post-World War I recovery, but that seems a bit of a stretch. It’s extraordinary that no formal competition was ever staged for such a mammoth government-funded project. The powers-that-be named Henry Bacon as architect after rejecting just one other designer; and Bacon turned immediately to his longtime partner French even after a campaign to save money by commissioning a reproduction of the 1887 Chicago statue by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Abraham Lincoln: The Man. Fortunately, every subsequent decision worked out beautifully. Bacon insisted on a Greek-style temple. French rejected the idea of a standing Lincoln, chose marble over bronze, and once he saw the interior atrium for himself, insisted on making the statue 19-feet high instead of the originally proposed 12. Then DCF hired a family of Italian immigrant stonecutters to enlarge and carve the behemoth in the Bronx—another perfect choice. The final result was everything one had hoped—both grand yet somehow intimate, and extraordinarily harmonious with its setting. Can anyone today imagine it looking anything other than it looks? Yet things could have gone wrong half a dozen times—for example, some influential men wanted to build the Memorial at the Capitol, or at the Soldiers’ Home. When the influential Congressman “Uncle Joe” Cannon rejected the western fringe of Potomac Park because he judged it a “god damned swamp.” He threatened to place it instead at Arlington—in the old Confederacy! Swampy or not, it ended up where it was almost ordained to be—at the western edge of the Mall—thanks in large part to the urging of Secretary of State John Hay, Lincoln’s own former White House secretary, who thought the site should be remote—but not too remote.

SG: Who wrote the words inscribed in the Memorial?

IN THIS TEMPLE

AS IN THE HEARTS OF THE PEOPLE

FOR WHOM HE SAVED THE UNION

THE MEMORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

IS ENSHRINED FOREVER

HH: It’s a puzzling story. French originally wanted his friend Robert Underwood Johnson of Century Magazine to do the epigraph. Johnson had edited Battles and Leaders of the Civil War but otherwise was a curious choice to be what French called “my poet laureate.” He was best known as an editor, not a writer. For some reason, it didn’t pan out; maybe Johnson’s first draft got rejected—maybe he lost interest—we just don’t know (or at least I could not find the answer). In any event, French turned to yet another unlikely candidate: the New York Tribune’s art critic, a fellow named Royal Cortissoz, who had been very generous in praise of French. He composed an epigraph before he was even asked to do so. And French loved the result. Like the sculptor, Cortissoz was a traditionalist who didn’t much care for modern and abstract art. The words today qualify almost as American scripture, but in its day they were roundly criticized. The man who succeeded French as head of the National Commission of Fine Arts called the epigraph “poor, cheap, sentimental, erroneous, disfiguring.” Now it seems to capture and enhance the mood magnificently—at least for me. If only it had mentioned emancipation as well as union—that unfortunate omission constitutes its one shortcoming. We have to remember that the Lincoln Memorial was designed to promote sectional reconciliation, not racial reconciliation. Thanks to those who staged their protests there, however, its power to inspire racial healing is what it is now best known for.

[Harold Holzer is Jonathan F. Fanton Director of Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. His book Monument Man: The Life & Art of Daniel Chester French was published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2019.]